| Rabbit-Proof Fence | |

|---|---|

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Phillip Noyce |

| Screenplay by | Christine Olsen |

| Based on | Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara |

| Produced by | Phillip Noyce Christine Olsen John Winter |

| Starring | Everlyn Sampi Tianna Sansbury Laura Monaghan David Gulpilil Kenneth Branagh |

| Cinematography | Christopher Doyle |

| Edited by | Veronika Jenet John Scott |

| Music by | Peter Gabriel |

Production companies | |

| Distributed by | Becker Entertainment |

Release date |

|

Running time | 93 minutes[1] |

| Country | Australia |

| Languages | Walmajarri English |

| Budget | USD$6 million |

| Box office | USD$16.2 million |

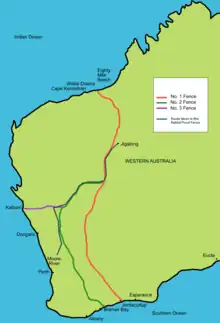

Rabbit-Proof Fence is a 2002 Australian drama film directed and produced by Phillip Noyce based on the 1996 book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence by Doris Pilkington Garimara. It is loosely based on a true story concerning the author's mother Molly Craig, aunt Daisy Kadibil and cousin Gracie, who escaped from the Moore River Native Settlement, north of Perth, Western Australia, to return to their Aboriginal families, after being placed there in 1931. The film follows the Aboriginal girls as they walk for nine weeks along 1,500 miles (2,400 km) of the Australian rabbit-proof fence to return to their community at Jigalong, while being pursued by white law enforcement authorities and an Aboriginal tracker.[2] The film illustrates the official child removal policy that existed in Australia between approximately 1905 and 1967. Its victims now are called the "Stolen Generations".

The soundtrack to the film, called Long Walk Home: Music from the Rabbit-Proof Fence, is by Peter Gabriel. British producer Jeremy Thomas, who has a long connection with Australia, was executive producer of the film, selling it internationally through his sales arm, HanWay Films. In 2005 the British Film Institute included it in the BFI list of the 50 films you should see by the age of 14.

Plot

In 1931, two sisters – 14-year-old Molly and 8-year-old Daisy – and their 10-year-old cousin Gracie live in the Western Australian town of Jigalong. The town lies along the northern part of one of the fences making up Australia's rabbit-proof fence (called Number One Fence), which runs for over one thousand miles.

Over a thousand miles away in Perth, the official Protector of Western Australian Aborigines, A. O. Neville (called Mr. Devil by them), signs an order to relocate the three girls to the Moore River Native Settlement. The children are referred to by Neville as "half-castes", because they have one white and one Aboriginal parent. Neville's reasoning is portrayed as: the Aboriginal people of Australia are a danger to themselves, and the "half-castes" must be bred out of existence. He plans to place the girls in a camp where they, along with all half-castes of that age range, both boys and girls, will grow up. They will then presumably become labourers and servants to white families, regarded as a "good" situation for them in life. Eventually if they marry, it will be to white people and thus the Aboriginal "blood" will diminish. As such, the three girls are forcibly taken from their families at Jigalong by a local constable, Riggs, and sent to the camp at the Moore River Native Settlement, in the south west, about 90 km (55 miles) north of Perth.

While at the camp, the girls are housed in a large dormitory with dozens of other children where they are strictly regimented by nuns. They are prohibited from speaking their native language, forced to pray, and subject to corporal punishment for any infractions of the camp's rules. Attempts at escape are also harshly punished. During an impending thunderstorm that will help cover their tracks, Molly convinces the girls to escape and return to their home.

During their flight, the girls are relentlessly pursued by Moodoo, a tracker from the camp. They eventually find their way back to the rabbit-proof fence, which will lead them toward their home. They follow the fence for months, just barely escaping capture several times. Neville spreads word that Gracie's mother is waiting for her in the town of Wiluna. The information finds its way to an Aboriginal traveller who "helps" the girls. He tells Gracie about her mother and says they can get to Wiluna by train, causing her to leave the other two girls in an attempt to catch a train to Wiluna. Molly and Daisy soon walk after her and find her at a train station. They are not reunited, however, as Riggs appears and Gracie is recaptured. The betrayal is revealed by Riggs, who tells the man he will receive a shilling for his help. Knowing they are powerless to aid her, Molly and Daisy continue their journey. In the end, after a nine-week journey through the harsh Australian outback, having walked the 2,400 km (1,500 miles) route along the fence, the two sisters return home and go into hiding in the desert with their mother and grandmother. Meanwhile, Neville realizes he can no longer afford the search for Molly and Daisy and decides to end it.

Epilogue

The film's epilogue shows recent footage of Molly and Daisy. Molly explains that Gracie has died and she never returned to Jigalong. Molly also tells us of her own two daughters; she and they were taken from Jigalong back to Moore River. She managed to escape with one daughter, Annabelle, and once again, she walked the length of the fence back home. However, when Annabelle was three years old, she was taken away once more, and Molly never saw her again. In closing, Molly says that she and Daisy "... are never going back to that place".

Cast

- Everlyn Sampi as Molly Craig

- Tianna Sansbury as Daisy Craig Kadibil

- Laura Monaghan as Gracie Fields

- David Gulpilil as Moodoo the Tracker

- Jason Clarke as Constable Riggs

- Kenneth Branagh as A. O. Neville

- Ningali Lawford as Maude, Molly's mother

- Myarn Lawford as Molly's grandmother

- Deborah Mailman as Mavis

- Garry McDonald as Mr. Neal

- Roberta Lynch as The Teacher

- Roy Billing as Police Inspector

- Natasha Wanganeen as Nina, Dormitory Boss

Production

The film is adapted from the book Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence, by Doris Pilkington Garimara, which is the second book of her trilogy documenting her family's stories.[3] The other two books are Caprice: A Stockman’s Daughter (1991) and Under the Wintamarra Tree (2002)

Reception

Public reception

The film stirred controversy in Australia relating to the government's historical policy of removing part-Aboriginal children, who became known as the Stolen Generations, from Aboriginal communities and placing them in state institutions.[4][5] Eric Abetz, a government minister, announced the publishing of a leaflet criticising the film's portrayal of the treatment of indigenous Australians, and demanded an apology from the filmmakers. Director Phillip Noyce suggested instead that the government apologise to the indigenous people affected by the removal policy.[4]

Conservative commentators such as Andrew Bolt also attacked the historical accuracy of the film. Bolt criticised the numerous disparities between the film and Pilkington Garimara's novel, a fact that angered Pilkington Garimara, who said that Bolt had misquoted her.[4] The academic Robert Manne in turn accused Bolt of historical denialism, and scriptwriter Christine Olsen wrote a detailed response to Bolt's claims.[5]

Olsen attributed the angry response among some of the public to the fact that it was based in events that were "demonstrably true" and well-documented.[4] However, the filmmaker said that the film was meant primarily as a drama rather than a political or historical statement. Noyce stated, "If drama comes from conflict, there's no greater conflict in Australian history than the conflict between indigenous Australians and white settlers."[4]

The historian Keith Windschuttle also disputed the film's depiction of events, stating in his work The Fabrication of Aboriginal History that Molly and the two other girls had been removed for their own welfare, and that the two older girls had been sexually involved with white men. Noyce and Olsen rejected these criticisms, stating that Windschuttle's research was incomplete.[6] Pilkington Garimara denied Windschuttle's claims of sexual activity between her mother and local whites, stating that the claims were a distortion of history.[7]

Critical response

The film received positive reviews from critics. Rotten Tomatoes gave it a rating of 87% based on 142 reviews, with an average rating of 7.6/10. The site's consensus states, "Visually beautiful and well-acted, Rabbit-Proof Fence tells a compelling true-life story."[8] On Metacritic the film has a score of 80 out of 100, indicating "generally favorable reviews".[9]

David Stratton of SBS awarded the film four stars out of five, commenting that Rabbit-Proof Fence is a "bold and timely film about the stolen generations."[10]

Box office

Rabbit-Proof Fence grossed $16.2 million worldwide, including $3.8 million in Australia.[11]

Accolades

Wins

- 2001 – Queensland Premier's Literary Awards.[12]

- Film Script—the Pacific Film and Television Commission Award (Christine Olsen)[13]

- 2002 – Australian Film Institute Awards[14]

- Best Film (Phillip Noyce, Christine Olsen, John Winter)

- Best Original Music Score (Peter Gabriel)

- Best Sound (Bronwyn Murphy, Craig Carter, Ricky Edwards, John Penders)

- 2002 – Film Critics Circle of Australia Awards[15]

- Best Director (Phillip Noyce)

- Best Screenplay—Adapted (Christine Olsen)

- 2002 – Inside Film Awards[16]

- Best Actress (Everlyn Sampi)

- Best Production Design (Roger Ford)

- 2002 – New South Wales Premier's History Awards[17]

- shortlisted for The Premier's Young People's History Prize (Christine Olsen and Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (United States) – Aspen Filmfest[18]

- Audience Award, Audience Favourite Feature[19] (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (Switzerland) – Castellinaria International Festival of Young Cinema,[20]

- ASPI Award (Phillip Noyce)

- Golden Castle (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (United States) – The 2002 Starz Encore Denver International Film Festival[21]

- People's Choice Award: Best Feature-Length Fiction Film (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (South Africa) – Durban International Film Festival[22]

- Audience Award (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (United Kingdom) – Edinburgh International Film Festival[23]

- Audience Award (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (United Kingdom) – Leeds International Film Festival[24]

- Audience Award (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (United States) – National Board of Review Awards 2002[25]

- Freedom of Expression Award

- Best Director (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (United States) – San Francisco Film Critics Circle[26]

- Special Citation (Phillip Noyce, also for The Quiet American (2002))

- Audience Award: Best Foreign Film (Phillip Noyce)

- 2002 (Spain) – Valladolid International Film Festival[27]

- Audience Award: Feature Film (Phillip Noyce)

- 2003 (United Kingdom) – London Critics Circle Film Awards (ALFS)[28]

- Director of the Year (Phillip Noyce, also for The Quiet American (2002))

- 2003 (Brazil) – São Paulo International Film Festival[29]

- Audience Award: Best Foreign Film (Phillip Noyce)

Nominations

- 2002 (Australia)

- Australian Film Institute Nominations[30]

- Best Actor in a Supporting Role (David Gulpilil)

- Best Cinematography (Christopher Doyle)

- Best Costume Design (Roger Ford)

- Best Direction (Phillip Noyce)

- Best Editing (Veronika Jenet, John Scott)

- Best Production Design (Roger Ford)

- Best Screenplay Adapted from Another Source (Christine Olsen)

- 2002 (Australia)

- Film Critics Circle of Australia Nominations[15] Australia

- Best Actor—Female (Everlyn Sampi)

- Best Cinematography (Christopher Doyle)

- Best Film

- Best Music Score (Peter Gabriel)

- 2002 (Poland)

- Camerimage—2002 International Film Festival of the Art of Cinematography[31]

- Golden Frog (Christopher Doyle)

- 2002 (United States)

- Golden Trailer Award Nominations[32]

- Golden Trailer: Best Independent

- 2003 (United States)

- Golden Globe Nominations[33]

- Golden Globe: Best Original Score—Motion Picture (Peter Gabriel)

- 2003 (United States)

- Motion Picture Sound Editors Nomination[34]

- Golden Reel Award: Best Sound Editing in Foreign Features (Juhn Penders, Craig Carter, Steve Burgess, Ricky Edwards, Andrew Plain)

- 2003 (United States)

- Political Film Society Awards[35]

- Exposé

- Human Rights

- 2003 (United States)

- Young Artist Awards[36]

- Best Performance in a Feature Film—Supporting Young Actress (Everlyn Sampi)

- Best Performance in a Feature Film—Young Actress Age Ten or Under (Tianna Sansbury)

See also

- Cinema of Australia

- Survival film, about the film genre, with a list of related films

References

- ↑ "Rabbit-Proof Fence (PG)". British Board of Film Classification. 24 July 2002. Retrieved 2 January 2012.

- ↑ "Rabbit-Proof Fence Title Details". National Film and Sound Archive. Retrieved 28 July 2007.

- ↑ Brewster, Anne (2007). "The Stolen Generations: Rites of Passage: Doris Pilkington interviewed by Anne Brewster (22 January 2005)". The Journal of Commonwealth Literature. 42 (1): 143–159. doi:10.1177/0021989407075735. S2CID 220818218.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Fickling, David (25 October 2002). "Film: The stolen ones". The Guardian. London, UK.

- 1 2 Byrnes, Paul. "Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002): Curator's notes". Australian Screen Online. Canberra: National Film and Sound Archive.

- ↑ Maddox, Garry; Munro, Kelsey (15 December 2009). "Director, historian at odds over film". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 February 2018.

- ↑ Perpitch, Nicolas (15 December 2009). "Historian's Aboriginal claims a distortion, says author". The Australian. Sydney.

- ↑ Rabbit-Proof Fence at Rotten Tomatoes

- ↑ Rabbit-Proof Fence at Metacritic

- ↑ Stratton, David. "Rabbit-Proof Fence (review)". SBS. Retrieved 14 February 2013.

- ↑ "Rabbit-Proof Fence (2002)". Box Office Mojo. Retrieved 21 August 2020.

- ↑ "Premier's Literary Awards website". 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 28 May 2007.

- ↑ "Queensland Premier's Literary Awards". 26 June 2007. Archived from the original on 13 August 2007.

- ↑ "Australian Film Institute website". 29 June 2007.

- 1 2 "Film Critics Circle of Australia website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Lexus Inside Film Awards website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "NSW Premier's History Awards 2002". NSW Ministry for the Arts. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 17 July 2007.

- ↑ "Aspen Film website". 28 June 2007.

- ↑ "2002 Aspen Film Awards". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Castellinaria International Festival of Young Cinema". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Denver International Film website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Durban International Film Festival website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Edinburg International Film Festival website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Leeds International Film Festival website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "The National Board of Review, USA website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "San Francisco Film Critics Circle website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Valladolid International Film Festival website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "The Critics Circle". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "São Paulo International Film Festival website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Australian Film Institute website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Camerimage website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Golden Trailer Awards website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Golden Globe Awards website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Motion Picture Sound Editor website". 29 June 2007.

- ↑ "Political Film Society website". 29 June 2007. Archived from the original on 21 August 2007.

- ↑ "Young Artists Award website". 29 June 2007.

Further reading

- Pilkington, Doris (Nugi Garimara) (1996). Follow the Rabbit-Proof Fence. St. Lucia: University of Queensland Press. ISBN 978-0-70-222709-7.

External links

- Rabbit-Proof Fence at IMDb

- Rabbit-Proof Fence at AllMovie

- Rabbit-Proof Fence at Box Office Mojo

- Rabbit-Proof Fence at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rabbit-Proof Fence at Metacritic

- Phillip Noyce's shooting diary

- Phillip Noyce interview—Phillip Noyce on Rabbit-Proof Fence

- Rabbit Proof Fence at Oz Movies