Until 1965, racial segregation in schools, stores and most aspects of public life existed legally in Ontario, Quebec and Nova Scotia, and informally in other provinces such as British Columbia. Unlike in the United States, racial segregation in Canada applied to all non-whites and was historically enforced through laws, court decisions and social norms with a closed immigration system that barred virtually all non-whites from immigrating until 1962. Section 38 of the 1910 Immigration Act permitted the government to prohibit the entry of immigrants "belonging to any race deemed unsuited to the climate or requirements of Canada, or of immigrants of any specified class, occupation or character."[1]

Medical segregation

Indigenous peoples of Canada were treated in racially segregated hospitals called Indian hospitals or segregated wards in regular hospitals. Medical experimentation also occurred at these hospitals, frequently without consent, such as the testing of BCG vaccine on infants.[2] These hospitals were underfunded, overcrowded, and had worse quality of care for patients. Hospitals that exclusively treated white patients were often located nearby.[2]

Blood transfusions were segregated based on the donor's race.[3]

Immigration policy

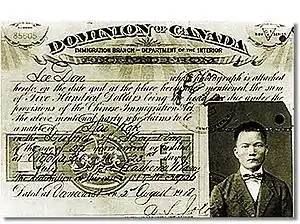

Responding to the anti-immigration sentiment in British Columbia, the Canadian government of John A. Macdonald introduced the Chinese Immigration Act, receiving Royal Assent and becoming law in 1885.[4] Under its regulations, the law stipulated that all Chinese people entering Canada must first pay a CA$50 fee,[5][6] later referred to as a head tax. This was amended in 1887,[7] 1892,[8] and 1900,[9] with the fee increasing to CA$100 in 1901 and later to its maximum of CA$500 in 1903, representing a two-year salary of an immigrant worker at that time.[6] However, not all Chinese arrivals had to pay the head tax; those who were presumed to return to China based on the apparent, transitory nature of their occupation or background were exempt from the penalty. These included arrivals identifying themselves as: students, teachers, missionaries, merchants, or members of the diplomatic corps.[4][10] The Government of Canada collected about $23 million ($354 million in 2021 dollars)[11] in face value from about 81,000 head tax payers.[12] The head tax did discourage Chinese women and children from joining their men,[12] but it failed to meet its goal, articulated by contemporary politicians and labour leaders, of the complete exclusion of Chinese immigration.[10] Such was achieved through the same law that ended the head tax: the Chinese Immigration Act of 1923, which stopped Chinese immigration entirely, albeit with certain exemptions for business owners and others.[13] It is sometimes referred to by opponents as the Chinese Exclusion Act, a term also used for its American counterpart.[14]

Amber Valley was home to one of the largest Black settlements in Canada. The majority of settlers had emigrated from Oklahoma, Texas, and other southern states in the US with the desire to flee from the racial violence they faced there. Other Black communities in Alberta were Wildwood and Campsie. Land was open to settlers through the Dominion Lands Act, with the intent of preventing the Canadian prairies from being claimed as territory of the United States. Then, Black settlers were essentially banned as a result of actions taken by prime minister Wilfrid Laurier's government.[15]

Education

Black Canadians were racially segregated in primary schools by the mid-19th century. Ontario and Nova Scotia set up legally segregated schools to keep black students separate from white students. Black students had to attend different schools or attend at different times. In some other provinces, white families enforced an informal segregation by blocking black students from attending school. The last segregated school in Ontario closed in 1965; the last one in Nova Scotia closed in 1983. Canadian universities, particularly medical schools, often rejected applications on the basis of race. This was the case of Dalhousie University, the University of Toronto, McGill University and Queen's University. Admitted black students and Jewish people faced restrictions that white, Christian students did not have. Only a few hospitals accepted black medical interns.[1]

Employment

Racial segregation practices extended to many areas of employment in Canada. White business owners and even provincial and federal government agencies often did not hire black people, with explicit rules preventing their employment. When the labour movement took hold in Canada near the end of the 19th century, workers began organizing and forming trade unions with the aim of improving the working conditions and quality of life for employees. However, black workers were systematically denied membership to these unions, and worker's protection was reserved exclusively for whites.[1]

Racial segregation in individual provinces and territories

Alberta

Alberta had an increased rate of black immigration from the United States in the early 1900s, partially due to black fur-traders seeking employment. In Edmonton, the city council passed a 1911 motion to end further black immigration. The council claimed that black immigration was detrimental to the province and that black and white Albertans were not capable of coexistence. The Ku Klux Klan in Canada also had increased local activity during the 1920s and 1930s.[16] In the 1920s, city officials in Calgary codified restrictive covenants to prevent non-whites from purchasing homes outside of the boundaries of the railway yards.[1]

Lulu Anderson, a black woman, was denied admission to the Metropolitan Theatre in Edmonton. In November 1922, Anderson sued the theatre for refusing to sell her a ticket to watch a movie, but the provincial courts ruled in favour of the theatre owners.[16]

British Columbia

Land titles with restrictive covenant clauses were used to prevent the sale or rental of property to non-whites. For example, a clause in Vancouver real estate deeds for entire neighbourhoods going back to at least 1928 and included as late as 1965 stated, "That the Grantee or his heirs, administrators, executor, successors or assigns will not sell to, agree to sell to, rent to, lease to, or permit or allow to occupy, the said lands and premises, or any part thereof, any person of the Chinese, Japanese or other Asiatic race or to any Indian or Negro."[1]

A long-standing practice of national segregation has also been imposed upon the commercial salmon fishery in British Columbia since 1992 when separate commercial fisheries were created for select aboriginal groups on three B.C. river systems. Canadians of other nations who fish in the separate fisheries have been arrested, jailed and prosecuted. Although the fishermen who were prosecuted were successful at trial in R v Kapp,[17] this decision was overturned on appeal.[18]

A CBC panel in Vancouver in 2012 discussed the growing public fear that the proliferation of ethnic enclaves amounted to a type of self-segregation.[19]

Ontario

In Sarnia, a 1946 property deed for a Lake Huron community of approximately 100 cottage lots specified that property could only be owned by whites of a particular racial background. These clauses were all upheld by court decisions, until the Canadian constitution came into effect.[1]

In 1944, Ontario enacted the Racial Discrimination Act, which prohibited the publication or display, of any notice, sign, symbol, emblem or other representation on lands, premises, by newspaper or radio, that indicated racial discrimination.[20]

Nova Scotia

In 1946, Viola Desmond, a black woman, refused to leave the segregated whites-only section of the Roseland Theatre in New Glasgow, Nova Scotia. Viola Desmond was arrested, jailed overnight and convicted without legal representation for an obscure tax offence as a result. Despite the efforts of the Nova Scotian Black community to assist her appeal, Viola Desmond was unable to remove the charges against her and went unpardoned in her lifetime.[1]

Quebec

Before becoming a province, Quebec was known as New France, which was a French colony. As a French colony, slavery existed under Le Code Noir.[21] This influenced later policies where black people were seen as inferior to white people. In the education system, black children were streamed into different careers, creating a segregated workforce. In the 1950s, black women were only permitted to settle in Quebec if they were domestic workers.[22]

In 1936, Fred Christie and another black acquaintance Emile King, were refused service at the York Tavern in the Forum in Montreal after watching a boxing match. Christie sued for $200 and won in provincial court. Christie was awarded $25 and the tavern was ordered to pay his court costs. The tavern owners successfully appealed. Christie took his case all the way to the Supreme Court of Canada in 1939. They dismissed his case, arguing that private businesses were able discriminate based on race on their choosing. Few taverns in Saskatchewan, Ontario, and British Columbia allowed black visitors, and those that did had designated tables or side rooms for non-whites.[1]

Saskatchewan

In 1901, Yee Clun was a Chinese émigré to Regina. He opened a restaurant and was an influential member of the local community, heading the local branch of the Chinese National Party. Clun had difficulty hiring employees as the Chinese Exclusion Act of 1923 had gone into effect. As a result, he filed an application with the city council to permit him to hire white women as employees, as Chinese business owners were not allowed to do so. His request gained preliminary approval but was delayed. The majority of the members in the local Women's Christian Temperance Union protested this, as they were concerned that this would lead to more white women wanting to marry Chinese men. The Regina Local Council of Women also urged the council to reject the application. This resulted in a decision that no licences for hiring female employees could be granted to Chinese men.[23]

See also

External links

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Henry, Natasha (8 September 2021). "Racial Segregation of Black People in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia.

- 1 2 Lux, Maureen. "Indian Hospitals in Canada". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 5 June 2022.

- ↑ Mwamba, Nseya. Separate but Equal: The Black Racial Classification in the Canadian Blood System (Thesis). University of Ottawa.

- 1 2 Canada. Dept. of Trade and Commerce (1885), Chinese Immigration Act, 1885, retrieved September 1, 2007

- ↑ "Chinese Head Tax and Exclusion Act". CCNC. July 1, 1923. Archived from the original on April 13, 2017. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- 1 2 "Chinese-Canadian Genealogy - Chinese Head Tax". Vpl.ca. January 1, 1902. Archived from the original on June 28, 2013. Retrieved May 13, 2013.

- ↑ Canada. Dept. of Trade and Commerce (1887), An act to amend the Chinese Immigration Act, 1887, retrieved September 1, 2007

- ↑ Canada. Dept. of Trade and Commerce (1892), An act to further amend the Chinese Immigration Act, 1892, retrieved September 1, 2007

- ↑ Canada (1901), Act respecting and restricting Chinese immigration, retrieved September 1, 2007

- 1 2 Vancouver Public Library (2007), Chinese Head Tax, archived from the original on October 1, 2007, retrieved September 1, 2007

- ↑ 1688 to 1923: Geloso, Vincent, A Price Index for Canada, 1688 to 1850 (December 6, 2016). Afterwards, Canadian inflation numbers based on Statistics Canada tables 18-10-0005-01 (formerly CANSIM 326-0021) "Consumer Price Index, annual average, not seasonally adjusted". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 17, 2021. and table 18-10-0004-13 "Consumer Price Index by product group, monthly, percentage change, not seasonally adjusted, Canada, provinces, Whitehorse, Yellowknife and Iqaluit". Statistics Canada. Retrieved April 17, 2021.

- 1 2 "Asian Immigration", Canada in the Making, 2005, archived from the original on May 10, 2010, retrieved September 1, 2007

- ↑ Morton, James. 1974. In the Sea of Sterile Mountains: The Chinese in British Columbia. Vancouver: J.J. Douglas.

- ↑ "Chinese Canadian Recognition and Restitution Act". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). House of Commons, Canada. April 18, 2005. p. 1100.

- ↑ Derworiz, Collette. "'One of the biggest Black settlements in Western Canada' has a rich history". CBC. Retrieved 16 October 2022.

- 1 2 Mohamed, Bashir. "Lulu Anderson". The Canadian Encyclopedia. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ "R. v. Kapp et al – Reasons for Judgment". Provincialcourt.bc.ca. Archived from the original on 1 October 2008. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ↑ "2004 BCSC 958 R. v. Kapp et al". Courts.gov.bc.ca. 12 July 2004. Retrieved 15 February 2011.

- ↑ Greenholtz, Joe (13 June 2012). "Fear and the 'problem' of city's ethnic enclaves". Richmond News. Retrieved 8 August 2022.

- ↑ Bradburn, Jamie. "'A necessity for the well-being and progress of society': Ontario's Racial Discrimination Act turns 75". TVO. Retrieved 2 April 2023.

- ↑ Buchanan, Kelly (13 January 2011). "Slavery in the French Colonies: Le Code Noir (the Black Code) of 1685". The Library of Congress. Retrieved 4 February 2023.

- ↑ Williams, Dorothy. "When it comes to systemic racism, history belies your words, Mr. Legault". CBC News. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ↑ Blackhouse 1999, p. 151-154.

Sources

- Blackhouse, Constance (1999). Colour-Coded: A Legal History of Racism in Canada, 1900-1950. University of Toronto Press. pp. 1–431. ISBN 0-8020-8286-6.