.png.webp)

As in other Polynesian islands, Rapa Nui tattooing had a fundamentally spiritual connotation. In some cases the tattoos were considered a receptor for divine strength or mana. They were manifestations of the Rapa Nui culture. Priests, warriors and chiefs had more tattoos than the rest of the population, as a symbol of their hierarchy. Both men and women were tattooed to represent their social class.[2][3]

Process

The tattooing process was performed with bone needles and combs called uhi or iuhi made out of bird or fish bones.[3][4] The ink was made out of natural products, primarily from the burning of Ti leaves (Cordyline terminalis) and sugar cane.[5][3] The other end has two grooves so that a rod can be attached to the end, which probably helps the artist maneuver the needles during the tattoo process.[3] Tattoos are applied with the needle combs and a wooden mallet called miro pua ‘uhi.[6]

Names

The tattoos were named based on its location on the body:

- Rima kona: On the back of the hand or wrist.

- Retu: On the forehead.

- Matapea: Under the eyes.

- Pangaha’a: On the cheeks.

- Pare: On the arms.

- Humu: On the thighs and/or calves.

- Tu’u haino ino: On the back and buttocks.

History

Design

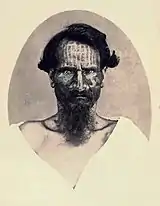

Tattoos, as well as other forms of art in Rapa Nui, blends anthropomorphic and zoomorphic imagery.[3] The most common symbols represented were of the Make-Make god, Moais, Komari (the symbol of female fertility), the manutara, and other forms of birds, fish, turtles or figures from the Rongo Rongo tablets.[5] Certain designs were more common than others. Women and men very often had heavy lines on their faces, which, crossing the forehead, extended from one ear to the other.[3] These lines were curved and combined with a series of large dots (humu or puraki, “to enclose”) that marked the forehead and temples. They are also seen on existing barkcloth figures, but in smaller detail.[3] Parallel lines across the forehead and the fringe of dots were the first motifs tattooed on the face. This pattern was the most general, and it was commonly recorded by early voyagers.[3] There are several tattoo patterns and figures mentioned in the research. One woman had an ‘ao, which is a ceremonial paddle, tattooed on her back.[3] Fischer also mentions an old woman with a paddle on her back, but calls it a rapa, which is a dance paddle that was tattooed when she lost her virginity. For her, the paddle reminded her of her first lover.[6] A German marine who visited the island told of “birds and strange beasts” tattoos.[6] Most men and women were covered from head to toe with different patterns and images.[6]

Status

The tattoos also varied by rank and status. Priests usually had more tattoos to distinguish themselves from the rest, while men and women had tattoos that distinguished their class identity from others.[4]

Modern day

Nowadays, young people are bringing back Rapa Nui tattoos as an important part of their culture and local artists base their creations on traditional motifs.

Meaning

Spiritual

Spiritually, tattoos were important because they were considered a gateway to divine strength. Other images included those that represented gods and other spiritual messages.[4]

Cultural

Sebastian Englert refers to the tattooing, also called Tatú or Tá kona, as a form of natural expression among the islanders, commonly seeing both adults and children with these paintings.[7] "Ta," means to write or engrave and "kona," means place. The whole word means something like "the place to engrave".[8]

References

- ↑ Stolpe, Hjalmar (1899). "Über die Tätowirung der Oster-Insulaner." Abhandlungen und Berichte des Königlischen. Zoologischen und Antropologisch-Ethnographischen Museums zu Dresden 8, no. 6.

- ↑ Kjellgren, Eric (2002). Splendid isolation: art of Easter Island; [published in conjunction with the Exhibition Splendid Isolation - Art of Easter Island, held at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, from December 11, 2001, to August 4, 2002]. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art [u.a.]

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Krutak, Lars (2005). "Sacred Skin: Easter Island Ink". Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- 1 2 3 "EASTER ISLAND | The complete guide of Rapa Nui". Imagina Easter Island (in European Spanish). Retrieved 2016-02-29.

- 1 2 "Rapa Nui Tattoo". Imagina, Ester Island, Complete Guide of Rapa Nui. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

- 1 2 3 4 Fischer, Steven R. (2005). Island at the End of the World: The Turbulent History of Easter Island. London, UK: Reaktion Books. pp. 27–31. ISBN 1861892454.

- ↑ Englert, Sebastian (1948). La tierra de Hotu Matu'a.

- ↑ Salinas, Margot Hotus (2006-04-08). "Rapa Nui and Its Tattooing Art". Ohmy News. Retrieved 2018-07-11.

Further reading

- Delsing, Riet. (2015). Articulating Rapa Nui : Polynesian cultural politics in a Latin American nation-state. Honolulu, HI: University of Hawaiʻi Press.

- Kjellgren, E., Van, T. J. A., Kaeppler, A. L., & Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.). (2001). Splendid isolation: Art of Easter Island. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art.

- Krutak, L. F. (2007). The tattooing arts of tribal women. London: Bennett & Bloom Desert Hearts.

- Arredondo, A. M., & Pilar, P. C. (2009). Rapa Nui: Takona tatu.

- Hunt, T. L., & Lipo, C. P. (2011). The statues that walked: Unraveling the mystery of Easter Island. New York: Free Press.

- Fiksa, Radomir (2019). Lexicon of Tribal Tattoos: Motifs, Meanings, and Origins. Schiffer