The Lantaka (Baybayin: pre virama: ᜎᜆᜃ: post virama: ᜎᜈ᜔ᜆᜃ) also known as rentaka (in Malay, jawi script: رنتاک) was a type of bronze portable cannon or swivel gun, sometimes mounted on merchant vessels and warships in Maritime Southeast Asia.[1] It was commonly equipped by native seafaring vessels from the Philippines, Indonesia, Brunei, and Malaysia.[2] Lela and rentaka are known by the Malays as meriam kecil (lit. "small cannon"),[3][4] the difference is that rentaka is smaller in length and bore than a lela.[5]: 122–123 and Lantakas are often called Kanyon in Filipino (literal meaning cannon).

The lantaka was cited by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts of the Philippines as an intangible cultural heritage of the country under the 'Traditional Craftsmanship' category that the government may nominate in the UNESCO Intangible Cultural Heritage Lists. The documentation of the craft was aided by ICHCAP of UNESCO.[6]

| Part of a series on |

| Cannons |

|---|

_Fauconneau_de_1589.jpg.webp) |

Etymology

The name may stem from the Malay word lantak, which means "hammering down" or "ramming down",[7]: 123 referencing its loading process (muzzle-loading). Ramrod in Malay is called pelantak.[8]: 613 The Malay word rentak means "stamping the feet in anger",[8]: 340 [7]: 182 "pounding the feet together".[9]

Description

.jpg.webp)

The lantaka is the "younger sibling" of the lela; they are smaller, with a length of less than 100 cm.[5]: 122–123 Typically, the bore diameters of these cannons were in the range of about 10–50 mm.[3] Many of these guns were mounted on swivels (called cagak in Malay)[3] and were known as swivel guns. The smaller ones could be mounted almost anywhere including in the rigging. Medium-sized cannons were frequently used in reinforced sockets on the vessel's rails and were sometimes referred to as rail guns. The heaviest swivel guns were mounted on modified gun carriages to make them more portable.

History

The origin of gunpowder-based weaponry in the Nusantara archipelago can be traced from the late 13th century. The Mongol invasion of Java brought gunpowder technology to Java in the form of a cannon (Chinese: 炮—"Pào").[10]: 1–2 [11][12]: 220 This resulted in eastern-style cetbang which is similar to Chinese cannon. Swivel guns, however only developed in the archipelago because of the close maritime relations of the Nusantara archipelago with the territory of west India after 1460 CE, which brought new types of gunpowder weapons to the archipelago, likely through Arab intermediaries. This weapon seems to be cannon and gun of Ottoman tradition, for example the prangi, which is a breech-loading swivel gun. A new type of cetbang, called the western-style cetbang, was derived from the Turkish prangi. Just like prangi, this cetbang is a breech-loading swivel gun made of bronze or iron, firing single rounds or scatter shots (a large number of small bullets).[13]: 94–95

In Malaya

When the Portuguese first came to the Malacca Sultanate, they found a large colony of Javanese merchants under their own headmen; they were manufacturing their own cannon, which is deemed as important as sails in a ship.[14]

Most lantakas were made of bronze and the earliest ones were breechloaders.[15] Michael Charney (2004) pointed out that early Malay swivel guns were breech-loaded.[16]: 50 There is a trend toward muzzle-loading weapons during colonial times.[17] Nevertheless, when Malacca fell to the Portuguese in 1511, both breech-loading and muzzle-loading swivel guns were found and captured by the Portuguese.[16]: 50

De Barros mentions that with the fall of the Malacca Sultanate, Albuquerque captured 3000 out of 8000 artillery. Among those, 2000 were made from brass and the rest from iron, in the style of Portuguese berço (breech-loading swivel gun). All of the artillery had its proper complement of carriages which could not be rivaled even by Portugal.[18][19]: 22, 247 [20]: 127–128 Afonso de Albuquerque compared Malaccan gun founders as being on the same level as those of Germany. However, he did not state what ethnicity the Malaccan gun founder was.[20]: 128 [12]: 221 [21]: 4 Duarte Barbosa stated that the arquebus-maker of Malacca was Javanese.[22]: 69 The Javanese also manufactured their own cannon in Malacca.[14] Anthony Reid argued that the Javanese handled much of the productive work in Malacca before 1511 and in 17th century Pattani.[22]: 69

Wan Mohd Dasuki Wan Hasbullah explained several facts about the existence of gunpowder weapons in Malacca before its fall in 1511:[23]: 97–98

- No evidence showed that guns, cannons, and gunpowder are made in Malay states.

- No evidence showed that guns were ever used by the Malacca Sultanate before the Portuguese attack, even from Malay sources themselves.

- Based on the majority of cannons reported by the Portuguese, the Malays preferred small artillery.

The cannons found in Malacca were of various types: esmeril (1/4 to 1/2-pounder swivel gun, probably refers to cetbang or lantaka),[24] falconet (cast bronze swivel gun larger than the esmeril, 1 to 2-pounder, probably refers to lela),[24] medium saker (long cannon or culverin between a six and a ten-pounder, probably refers to meriam)[25] and bombard (fat, heavy and short cannon).[16]: 46 The Malays also have one beautiful large cannon sent by the king of Calicut.[16]: 47 [19]: 22

Despite having a lot of artillery and firearms, the weapons of Malacca were mostly and mainly purchased from the Javanese and Gujarati, where the Javanese and Gujarati were the operators of the weapons. In the early 16th century, before the Portuguese arrival, the Malays were a people who lacked firearms. The Malay chronicle, Sejarah Melayu, mentioned that in 1509 they do not understand “why bullets killed”, indicating their unfamiliarity with using firearms in battle, if not in ceremony.[21]: 3 As recorded in Sejarah Melayu:

Setelah datang ke Melaka, maka bertemu, ditembaknya dengan meriam. Maka segala orang Melaka pun hairan, terkejut mendengar bunyi meriam itu. Katanya, "Bunyi apa ini, seperti guruh ini?". Maka meriam itu pun datanglah mengenai orang Melaka, ada yang putus lehernya, ada yang putus tangannya, ada yang panggal pahanya. Maka bertambahlah hairannya orang Melaka melihat fi'il bedil itu. Katanya: "Apa namanya senjata yang bulat itu maka dengan tajamnya maka ia membunuh?"

After (the Portuguese) coming to Malacca, then met (each other), they shot (the city) with cannon. So all the people of Malacca were surprised, shocked to hear the sound of the cannon. They said, "What is this sound, like thunder?". Then the cannon came about the people of Malacca, some lost their necks, some lost their arms, some lost their thighs. The people of Malacca were even more astonished to see the effect of the gun. They said: "What is this weapon called that is round, yet is sharp enough to kill?" [26]: 254–255 [12]: 219

Asia Portuguesa by Manuel de Faria y Sousa recorded a similar story, although not as spectacular as described in Sejarah Melayu.[27]: 120–121 The Epic of Hang Tuah narrates a Malaccan expedition to the country of Rum (the Ottoman Empire) to buy bedil (guns) and large meriam (cannons) after their first encounter with the Portuguese in 1509 CE, indicating their shortage of firearms and gunpowder weapons.[28]: 205–248 [note 1] Malaccan expedition to Rum (Ottoman Turks) to buy cannons never actually happened, it was only mentioned in the fictitious literature Hikayat Hang Tuah, which in reality based on the sending of a series of Acehnese embassies to the Ottoman Empire in the 16th century.[29]

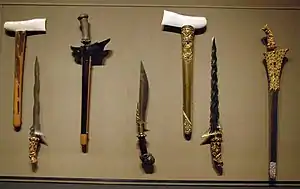

The Dutch and Portuguese quickly learned that they could trade cannons not only for spices and porcelain, but also for safe passage through pirate-infested waters. Local foundries continued to produce guns, using local patterns and designs from local brass and bronze objects. Stylized crocodiles, dolphins, birds, and dragons were common motifs.

In the Philippines

The ancient walled city of Cainta located in the opposite banks of the Pasig River,[30] is recorded as a fortified city with bamboo thickets and lantaka guns on its walls witnessed by the Spanish conquistadors on the Siege of Cainta in 1571.[30][31]

As described in an anonymous 1572 account documented in Volume 3 of Blair and Robertson's compiled translations:[30]

This said village had about a thousand inhabitants, and was surrounded by very tall and very dense bamboo thickets, and fortified with a wall and a few small culverins. The same river as that of Manilla circles around the village and a branch of it passes through the middle dividing it in two sections.

In the walls of old Manila, a gunsmith named Panday Pira[32][33] established a foundry on the northern bank of the Pasig River. Rajah Sulayman commissioned Panday Pira to cast the cannon that were mounted on the palisades surrounding his kingdom. In 1570, Castilian forces under the command of Martin de Goiti captured Manila and took these artillery pieces as war booty, presenting them to Miguel López de Legazpi, the first Spanish Governor-General of the Philippines.[34]

Local tradition

If a native vessel was unarmed, it was usually regarded by the local populace as improperly equipped and poorly decorated. Whether farmers, fishermen, or headhunters, the villagers who lived in the longhouses along Borneo's rivers lived in fear of being taken by pirates who used both vessel-mounted and hand-held cannons. Villages and tribesmen that were armed with mounted or handheld cannons had a distinct advantage over those who could only rely on bows and arrows, spears, blowguns and krises (swords).

Land transportation in the 17th and 18th century Java and Borneo was extremely difficult and cannons were fired for virtually all types of signaling. Whether they were fired in celebration of a birth or wedding, or to warn another hilltop fortress or riverbank fishing village of an impending attack, cannons were used to transmit messages telling of urgent or special events. Such events ranged from yellow fever and cholera epidemics to the start or finish of religious holidays such as Ramadan.

_from_the_Sulu_Archipelago%252C_brass%252C_Honolulu_Museum_of_Art.jpg.webp)

Distinguished visitors were ushered into longhouses with great ceremony, accompanied by the firing of the longhouse's cannon, much like today's 21-gun salute. These cannons were a display of the status and wealth of the extended family that controlled the longhouse.

All worked brass, bronze and copper had value and were used as trade items in early Borneo. Cannons were frequently part of the bride price demanded by the family of an exceptionally desirable bride or the dowry paid to the groom.

Many of the small cannons, often called personal cannons or hand cannons, had been received as honors and were kept and passed down in families, but in hard times they also served as a form of currency that could keep the family fed. As a recognized form of currency, cannons could be traded for rice, drums, canoes, tools, weapons, livestock, debts of honor, and even settlement of penalties for crimes ranging from the accidental death of a fellow villager to headhunting against another tribe.

Large cannons had the extra value of being used in both celebratory times and in warfare. The larger and/or more elaborate the cannon, the greater the trade value, and thus the greater the status of the owner.

Many of the finest cannons were given out by the Sultans of Brunei as part of ceremonies (such as birthdays or weddings) of the many princes and princesses of the extended Royal family. Cannons were frequently presented to guests along with awards and titles, and were meant to guarantee the recipients' allegiance to the Sultan. Mortars, cannon, and signal guns of all sizes were typically fired with colorful pyrotechnics on these occasions; the louder and more elaborate, the greater the honor.

Modern era

.jpg.webp)

In the 1840s England began suppressing piracy and headhunting and Rajah James Brooke (a wealthy Englishman who established the dynasty that ruled Sarawak from 1841 until 1946) distributed numerous Brunei cast hand cannons to guarantee the cooperation and allegiance of the local chiefs. Lantaka was used by Moro soldiers in the Moro Rebellion against U.S. troops in the Philippines.[35] They were also used by the Filipinos during the Philippine Revolution, this time copied from European models and cast from church bells. One cannon founder was a Chinese Filipino named Jose Ignacio Pawa, a blacksmith also.

Today these guns can be found on virtually all of the islands of the Pacific Rim, but they are most commonly found in the Muslim areas of Indonesia and Malaysia. The largest collection is in Brunei, where it is now illegal to export them. Even in other countries, a museum export permit is usually required.

These cannons are now highly sought after by collectors, with some of the realized prices exceeding $50,000 USD for a single gun. The more common guns can be bought for under $1,000. Replicas and forgeries of lantaka are known to exist in considerable numbers.[36]

Today most of the Christians in Mindanao and the Visayas refer the word "lantaka" to bamboo cannons (a noisemaker) or any improvised home-made noisemakers of the same firing mechanism usually made of bamboo tubes (Pula in Meranau or "Lapu"), segmented cans of condensed milk, or PVC pipes. They are usually used during New Year's Day celebrations as noisemakers, or often in medium-scale gang wars. The firing mechanism is the same as of the original lantaka, with denatured alcohol or calcium carbide mixed with water as its "gunpowder" (fuel) and a small lighted torch or lighter as the igniter.

See also

- Luthang, a bamboo toy gun from the Philippines that originally referred to small lantaka.

- Cetbang, earlier 14th century cannon used by Indonesian kingdoms.

- Lela, a type of cannon similar but larger than lantaka.

- Meriam kecil, a tiny version of meriam kecil (lela and lantaka) used mainly as a currency.

- Bedil (term), local term for gunpowder based weapons.

Notes

- ↑ Maka kata Laksamana, "Adapun hamba sekalian datang ini dititahkan oleh Sultan Melaka membawa surat dan bingkisan tanda berkasih-kasihan antara Sultan Melaka dan duli Sultan Rum, serta hendak membeli bedil dan meriam yang besar-besar. Adalah kekurangan sedikit bedil yang besar-besar di dalam negeri Melaka itu. Adapun hamba lihat tanah di atas angin ini terlalu banyak bedil yang besar-besar.”. Translation: Then the Admiral said, "As for our reason for coming here, we were ordered by the Sultan of Melaka to bring a letter and a gift of sympathy between the Sultan of Melaka and the Sultan of Rum, as well as to buy large guns and cannons. There is a shortage of large guns in the state of Melaka. While I see that the land above the wind has too many big guns."

References

- ↑ BLADE CULTURE AND THE ADVENT OF FIREARMS

- ↑ "Borneo Brass Cannon (Lantaka)". michaelbackmanltd.com. Retrieved 12 February 2020.

- 1 2 3 "Cannons of the Malay Archipelago". www.acant.org.au. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ↑ Teoh, Alex Eng Kean (2005). The might of the miniature cannon: A treasure of Borneo and the Malay Archipelago. Asean Heritage.

- 1 2 Ismail, Norain B.T. (2012). Peperangan dalam Historiografi Johor: Kajian Terhadap Tuhfat Al-Nafis. Kuala Lumpur: Akademi Pengajian Islam Universiti Malaya.

- ↑ "ICHCAP | e-Knowledge Center". www.ichcap.org. Archived from the original on 1 February 2018. Retrieved 15 January 2020.

- 1 2 Wilkinson, Richard James (1908). An Abridged Malay-English Dictionary (Romanised). Kuala Lumpur: F.M.S Government Press.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - 1 2 Wilkinson, Richard James (1901). A Malay-English dictionary. Hongkong: Kelly & Walsh, limited.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Departemen Pendidikan Nasional (2008). Kamus Besar Bahasa Indonesia Pusat Bahasa Edisi Keempat. Jakarta: PT Gramedia Pustaka Utama.

- ↑ Schlegel, Gustaaf (1902). "On the Invention and Use of Fire-Arms and Gunpowder in China, Prior to the Arrival of European". T'oung Pao. 3: 1–11.

- ↑ Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) Vol. 2. Paris: Editions de l'Ecole des Hautes Etudes en Sciences Sociales. Page 178.

- 1 2 3 Reid, Anthony (1993). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. Volume Two: Expansion and Crisis. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

- ↑ Averoes, Muhammad (2020). Antara Cerita dan Sejarah: Meriam Cetbang Majapahit. Jurnal Sejarah, 3(2), 89 – 100.

- 1 2 Furnivall, J. S. (2010). Netherlands India: A Study of Plural Economy. Cambridge University Press. p. 9

- ↑ Ooi, Keat Gin (2004). Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to East Timor. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 9781576077702.

- 1 2 3 4 Charney, Michael (2004). Southeast Asian warfare, 1300–1900. BRILL. ISBN 9789047406921.

- ↑ Hamid, Rahimah A. (2015). Kearifan Tempatan: Pandainya Melayu Dalam Karya Sastera. Penerbit USM. ISBN 9789838619332.

- ↑ Partington, J. R. (1999). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. JHU Press. ISBN 9780801859540. Retrieved 12 December 2014.

- 1 2 Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- 1 2 Birch, Walter de Gray (1875). The Commentaries of the Great Afonso Dalboquerque, Second Viceroy of India, translated from the Portuguese edition of 1774 volume 3. London: The Hakluyt Society.

- 1 2 Charney, Michael (2012). Iberians and Southeast Asians at War: the Violent First Encounter at Melaka in 1511 and After. In Waffen Wissen Wandel: Anpassung und Lernen in transkulturellen Erstkonflikten. Hamburger Edition.

- 1 2 Reid, Anthony (1989). The Organization of Production in the Pre-Colonial Southeast Asian Port City. In Broeze, Frank (Ed.), Brides of the Sea: Asian Port Cities in the Colonial Era (pp. 54–74). University of Hawaii Press.

- ↑ Hasbullah, Wan Mohd Dasuki Wan (2020). Senjata Api Alam Melayu. Dewan Bahasa dan Pustaka.

- 1 2 Manucy, Albert C. (1949). Artillery through the ages: A short illustrated history of the cannon, emphasizing types used in America. U.S. Department of the Interior Washington. p. 34.

- ↑ Lettera di Giovanni da Empoli, with introduction and notes by A. Bausani, Rome, 1970, page 138.

- ↑ Kheng, Cheah Boon (1998). Sejarah Melayu The Malay Annals MS RAFFLES No. 18 Edisi Rumi Baru/New Romanised Edition. Academic Art & Printing Services Sdn. Bhd.

- ↑ Koek, E. (1886). "Portuguese History of Malacca". Journal of the Straits Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 17: 117–149.

- ↑ Schap, Bot Genoot, ed. (2010). Hikayat Hang Tuah II. Jakarta: Pusat Bahasa. ISBN 978-979-069-058-5.

- ↑ Braginsky, Vladimir (2012-12-08). "Co-opting the Rival Ca(n)non the Turkish Episode of Hikayat Hang Tuah". Malay Literature. 25 (2): 229–260. doi:10.37052/ml.25(2)no5. ISSN 0128-1186.

- 1 2 3 Blair, Emma Helen; Robertson, James Alexander, eds. (1903). "Relation of the Conquest of the Island of Luzon". The Philippine Islands, 1493–1898. Vol. 3: 1569–1576. Translated by Gill, J. G. Ohio, Cleveland: Arthur H. Clark Company. p. 145.

- ↑ "Pre-Colonial Manila". Presidential Museum and Library. Archived from the original on 9 March 2016. Retrieved 27 April 2017.

- ↑ Jagor, Fedor. The Former Philippines thru Foreign Eyes. Retrieved September 8, 2009.

- ↑ "Panday Pira" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 21, 2011. Retrieved September 7, 2009.

- ↑ "Miguel López de Legazpi". paratodomexico.com.

- ↑ Gaysowski, Richard (2000). "Lantaka is one of several names for small hand carried rail guns". The Artilleryman. 22 (2). Archived from the original on 2011-07-07. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

- ↑ "used cannon for sale". Archived from the original on February 7, 2009. Retrieved 2009-07-05.

External links

- The Sea Research Society has a collection of over sixty of these guns, most dating from the 17th and 18th centuries.

- The Temple of Proportions, an online cultural center, has three more pictures of a gorgeous Lantaka.