| |

|---|---|

A Javanese bride and groom wearing their traditional garb | |

| Total population | |

| More than 100 million | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 95,217,022 (2010)[2] | |

| c. 5,000,000 (including Malaysian citizens counted as "Malays")[note 1] | |

| 1,500,000 (2014) (Javanese and Indonesian descent are often referred to as 'Al-Jawi' which means people from the Javanese islands (modern Indonesia))[6][7][8] | |

| c. 400,000 (including Singaporean citizens, more than 60% of Singaporean Malays are of Javanese descent)[9] | |

| 102,000 (2019) (Javanese Surinamese)[10] | |

| 21,700[11][12] | |

| 8,500[13] | |

| 4,100[14] | |

| 3,000[15] | |

| Languages | |

| |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Sunni Islam (97.15%) Minorities Christianity 2.56% (1.59% Protestant and 0.97% Roman Catholic), Hinduism (0.17%), Buddhist (0.10%), Others (0.01%)[16] | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

The Javanese (/dʒɑːvəˈniːz/, jah-və-NEEZ,[17] /dʒæv-/ jav-, /-ˈniːs/ -NEESS;[18] Indonesian: Orang Jawa; Javanese: ꦮꦺꦴꦁꦗꦮ, Wong Jawa (in Ngoko register); ꦠꦶꦪꦁꦗꦮꦶ, Tiyang Jawi (in Krama register))[19] are an Austronesian ethnic group native to the central and eastern part of the Indonesian island of Java. With more than 100 million people,[20] Javanese people are the largest ethnic group in both Indonesia and in Southeast Asia as a whole. Their native language is Javanese, it is the largest of the Austronesian languages in number of native speakers and also the largest regional language in Southeast Asia.[21] The Javanese as the largest ethnic group in the region have dominated the historical, social, and political landscape in the past as well as in modern Indonesia and Southeast Asia.[22]

There are significant numbers of Javanese diaspora outside of central and eastern Java regions, including the other provinces of Indonesia, as well as other countries such as Suriname, Singapore, Malaysia, Egypt, Saudi Arabia, South Africa, Sri Lanka, Yemen and the Netherlands.[23][24][25][26] The Javanese ethnic group has many sub-groups (based on native Javanese community on the island of Java) that can be distinguished based on their characteristics, customs, traditions, dialects, or even ways of life. These include Banyumasan, Cirebonese, Mataram, Osing, and Tenggerese.[27] The majority of the Javanese people identify themselves as Sunni Muslims, with a small minority identifying as Christians and Hindus. With a large global population, the Javanese are considered significant as they are the largest Muslim ethnic group in the Far East and the fourth largest in the world after the Arabs,[28] Bengalis,[29] and Punjabis.[30]

Javanese civilisation has been influenced by more than a millennium of interactions between the native animism Kejawen and the Indian Hindu—Buddhist culture, and this influence is still visible in Javanese history, culture, traditions, and art forms. The ancient Javanese kingdoms of Singhasari and Majapahit were among the most powerful maritime empires in the region, whose boundaries included most of Maritime Southeast Asia and parts of Indochina. Javanese heritage has created magnificent religious monuments such as Borobudur and Prambanan which are among the world's largest temples. Javanese culture has a strong influence in most of the Southeast Asian countries. In Brunei, Malaysia, and Singapore, the influence of Javanese culture can be seen in many aspects of modern Malay culture.[31] Javanese culture has greatly influenced their traditional cuisine with many dishes such as satay, sambal, ketupat, nasi kuning (pulut kuning), and rojak. Kris weapons, batik practice, gamelan musical instruments, ronggeng dance, and wayang kulit puppet[32] were introduced to them through Javanese contact. Javanese culture has also spread widely beyond Southeast Asia such as Sri Lanka, South Africa, and Suriname, where many of the Javanese diaspora live there.[33][34]

History

Like most Indonesian ethnic groups, including the Sundanese of West Java, the Javanese are of Austronesian origins whose ancestors are thought to have originated in Taiwan, and migrated through the Philippines[35] to reach Java between 1,500BC and 1,000BC.[36] However, according to recent genetic study, Javanese together with Sundanese and Balinese has almost equal ratio of genetic marker shared between Austronesian and Austroasiatic heritages.[37]

Ancient Javanese kingdoms and empires

Hindu and Buddhist influences arrived through trade contacts with the Indian subcontinent.[38] Hindu and Buddhist — traders and visitors, arrived in the 5th century. The Hindu, Buddhist and Javanese faiths blended into a unique local philosophy.[35]

The cradle of Javanese culture is commonly described as being in Kedu and Kewu Plain in the fertile slopes of Mount Merapi as the heart of the Mataram Kingdom.[39] The earliest Sanjaya and Sailendra dynasties had their power base there.[40]: 238–239 Between the late 8th century and the mid-9th century, the kingdom saw the blossoming of classical Javanese art and architecture reflected in the rapid growth of temple construction. The most notable of the temples constructed are Kalasan, Sewu, Borobudur and Prambanan.[41] At its peak, the Javanese kingdom had become a dominant empire that exercised its power—not only in Java island, but also in Sumatra, Bali, southern Thailand, Indianized kingdoms of the Philippines, and the Khmer in Cambodia.[42][43][44]

The centre of Javanese culture and politics was moved towards the eastern part of the island when Mpu Sindok (r. 929–947) moved the capital of the kingdoms eastward to the valleys of the Brantas River in the 10th century CE. The move was most likely caused by the volcanic eruption of Merapi and/or invasion from Srivijaya.[40]: 238–239

At the end of the 13th century, The major spread of Javanese influence occurred under King Kertanegara of Singhasari. The expansionist king launched several major expeditions to Madura, Bali in 1284,[45] Borneo, the Malay Peninsula, and most importantly to Sumatra in 1275.[40] He also extended Javanese involvement in the lucrative spice trade with the Maluku Islands. Following the defeat of the Melayu Kingdom in eastern Sumatra, Singhasari controlled trade in the Strait of Malacca.

Singhasari dominance was cut short in 1292 by Kediri's rebellion under Jayakatwang, killing Kertanegara. However, Jayakatwang's reign as king of Java soon ended as he was defeated by Kertanegara's son-in-law, Raden Wijaya with the help of invading Mongol troops in March 1293.

Raden Wijaya would later establish Majapahit near the delta of the Brantas River in modern-day Mojokerto, East Java. Kertanegara policies were later continued by the Majapahits under King Hayam Wuruk and his minister Gajah Mada,[45] whose reign from 1350 to 1389 was marked by conquests that extended throughout Southeast Asia. This expansion marked the greatest extent of Majapahit, making it one of the most influential empires in Indonesian and Southeast Asian history.[46]

Various kingdoms of Java were actively involved in the spice trade in the sea route of the Silk Road. Although not major spice producers, these kingdoms were able to stockpile spice by trading for it with rice, of which Java was a major producer.[47] Majapahit is usually regarded as the greatest of these kingdoms. It was both an agrarian and a maritime power, combining wet-rice cultivation and foreign trade.[48] The ruin of their capital can be found in Trowulan.

Javanese sultanates

Islam gained its foothold in port towns on Java's northern coast such as Gresik, Ampel Denta (Surabaya), Tuban, Demak and Kudus. The spread and proselytising of Islam among the Javanese was traditionally credited to Wali Songo.[49]

Java underwent major changes as Islam spread. Following succession disputes and civil wars, Majapahit power collapsed. After this collapse, its various dependencies and vassals broke free.[50] The Sultanate of Demak became the new strongest power, gaining supremacy among city-states on the northern coast of Java.[51] Aside from its power over Javanese city-states, it also gained overlordship of the ports of Jambi and Palembang in eastern Sumatra.[51] Demak played a major role in opposing the newly arrived colonial power, the Portuguese. Demak twice attacked the Portuguese following their capture of Malacca. They also attacked the allied forces of the Portuguese and the Sunda Kingdom, establishing in the process the Sultanate of Banten.

Demak was succeeded by the Kingdom of Pajang and finally the Sultanate of Mataram. The centre of power moved from coastal Demak, to Pajang in Blora, and later further inland to Mataram lands in Kotagede, near present-day Yogyakarta. The Mataram Sultanate reached its peak of power and influence during the reign of Sultan Agung Hanyokrokusumo between 1613 and 1645.

Colonial Java

In 1619 the Dutch established their trading headquarter in Batavia. Java slowly fell to the Dutch East India Company, which would also eventually control most of Maritime Southeast Asia. The internal intrigue and war of succession, in addition to Dutch interference, caused the Mataram Sultanate to break up into Surakarta and Yogyakarta. The further separation of the Javanese realm was marked by the establishment of the Mangkunegaran and Pakualaman princedom. Although the real political power in those days actually lay with the colonial Dutch, the Javanese kings, in their keratons, still held prestige as the supposed power centre of the Javanese realm, especially in and around Surakarta and Yogyakarta.

Dutch rule was briefly interrupted by British rule in the early 19th century. While short, the British administration led by Stamford Raffles was significant, and included the re-discovery of Borobudur. Conflict with foreign rule was exemplified by the Java War between 1825 and 1830, and the leadership of Prince Diponegoro.

Like the rest of the Dutch East Indies, Java was captured by the Empire of Japan during World War II. With Japan's defeat, independence was proclaimed in the new Republic of Indonesia.

Republic of Indonesia

When the Indonesian independence was proclaimed on 17 August 1945, the last sovereign Javanese monarchies, represented by the Sri Sultan of Yogyakarta, the Sunanate of Surakarta, Prince of Mangkunegara and Prince of Pakualaman declared that they would become part of the Republic of Indonesia.

Yogyakarta and Pakualaman were later united to form the Yogyakarta Special Region. The Sri sultan became Governor of Yogyakarta, and the Prince of Pakualaman became vice-governor; both were responsible to the President of Indonesia. The Special Region of Yogyakarta was created after the war of independence ended and formalized on 3 August 1950. Surakarta was later absorbed as part of the Central Java province.

Culture

The Javanese culture is one of the oldest civilizations and has flourished in Indonesia and Southeast Asia. It has gradually absorbed various elements and influences from other cultures, including native reverence for ancestral and natural spirits, Buddhist and Hindu dharmic values, Islamic civilization, and to a lesser extent, Christianity, Western philosophy and modern ideas.[52][53] Nevertheless, Javanese culture — especially in the Javanese cultural heartland; those of highly polished aristocratic culture of the keratons in Yogyakarta and Surakarta — demonstrates some specific traits, such as particular concern with elegance and refinement (Javanese: alus), subtlety, politeness, courtesy, indirectness, emotional restraint and consciousness to one's social stature.[54] Javanese culture values harmony and social order highly, and abhors direct conflicts and disagreements. These Javanese values are often promoted through Javanese cultural expressions, such as Javanese dance, gamelan, wayang and batik. It is also reinforced through adherence to Javanese adat (traditional rules) in ceremonies, such as Slametan, Satu Suro, Javanese weddings and Naloni Mitoni.

However, the culture of pesisiran of Javanese north coast and in Eastern Java demonstrates some slightly different traits. They tend to be more open to new and foreign ideas, more egalitarian, and less conscious of one's social stature. Some of these northern settlements — such as Demak, Kudus, Tuban, Gresik and Ampel in Surabaya — have become more overtly Islamic, traditionally because these port towns are among the earliest places that Islamic teachings gained foothold in Java.

Javanese culture is traditionally centered in the Central Java, Yogyakarta and East Java provinces of Indonesia. Due to various migrations, it can also be found in other parts of the world, such as Suriname (where 15% of the population are of Javanese descent),[55] the broader Indonesian archipelago region,[33] Cape Malay,[34] Malaysia, Singapore, Netherlands and other countries. The migrants bring with them various aspect of Javanese cultures such as Gamelan music, traditional dances[56] and the art of Wayang kulit shadow play.[57] The migration of Javanese people westward has created a coastal Javanese culture in West Java distinct from the inland Sundanese culture.

Language

Javanese is a member of the Austronesian family of languages and is closely related to, but distinct from, other languages of Indonesia.[58] It is notable for its great number of nearly ubiquitous Sanskrit loans, found especially in literary Javanese.[59] This is due to the long history of Hindu and Buddhist influences in Java.

Many Javanese in Indonesia are bilingual, being fluent in Indonesian (the standardized variant of the Malay language) and Javanese.[60]

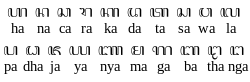

The Javanese language was formerly written with a script descended from the Brahmi script, natively known as Hanacaraka or Carakan. In addition, Javanese language can also written with right-to-left script descended from the Arabic script called Pegon. Upon Indonesian independence it was replaced with a form of the Latin alphabet. While Javanese was not made an official language of Indonesia, it has the status of regional language for communication in the Javanese-majority regions. The language also can be viewed as an ethnic language because it is one of the defining characteristics of the Javanese ethnic identity.[58]

Literature and philosophy

Javanese intellectuals, writers, poets and men of letters are known for their ability to formulate ideas and creating idioms for high cultural purpose, through stringing words to express a deeper philosophical meanings. Several philosophical idioms sprung from Javanese classical literature, Javanese historical texts and oral traditions, and have spread into several media and promoted as popular mottos. For example, "Bhinneka Tunggal Ika", used as the national motto of the Republic of Indonesia, "Gemah Ripah Loh Jinawi, Toto Tentrem Kerto Raharjo", "Jer Basuki Mawa Bea", "Rawe-Rawe rantas, Malang-Malang putung" and "Tut Wuri Handayani".[61]

Social structure

American anthropologist Clifford Geertz divided in the 1960s the Javanese community into three aliran or "streams": santri, abangan and priyayi. According to him, the Santri followed an orthodox interpretation Islam, the abangan followed a syncretic form of Islam that mixed Hindu and animist elements (often termed Kejawen), and the priyayi were the nobility.[62]

The Geertz opinion is often opposed today because he mixed the social groups with belief groups. It was also difficult to apply this social categorization in classing outsiders, for example other non-indigenous Indonesians such as persons of Arab, Chinese and Indian descent.

Social stratification is much less rigid in northern coast area.

Calendar

The Javanese calendar is used by the Javanese people concurrently with two other calendars, the Gregorian calendar and the Islamic calendar. The Gregorian calendar is the official calendar of Indonesia, while the Islamic calendar is used by Muslims and Indonesian government for religious worship and deciding relevant Islamic holidays. The Javanese calendar is presently used mostly for cultural events (such as Siji Suro). The Javanese calendar system is currently a lunar calendar adopted by Sultan Agung in 1633, based on the Islamic calendar. Previously, Javanese people used a solar system based on the Hindu calendar.

Unlike many other calendars, the Javanese calendar uses a 5-day week known as the Pasaran cycle. This is still in use today and is superimposed with 7-day week of the Gregorian calendar and Islamic calendar to become what is known as the 35-day Wetonan cycle.

Architecture

Historical temples located in Central Java and East Java

Throughout their long history, the Javanese have produced many important buildings, ranging from Hindu monuments, Buddhist stupa, mortuary temples, palace complexes, and mosques.

Before the rise of Islam, between the 5th to 15th centuries, Dharmic faiths (Hinduism and Buddhism) were the majority in the Indonesian archipelago, especially in Java. As a result, numerous Hindu temples, locally known as Candi, were constructed and dominated the landscape of Java. According to local beliefs, the Java valley had thousands of Hindu temples that co-existed with Buddhist temples, most of which were buried in the massive eruption of Mount Merapi in 1006 AD.[63]

Two important religious monuments are the Hindu temple of Prambanan and the Buddhist temple of Borobudur. Both of them are 9th century temples and UNESCO World Heritage Sites. Both are located near Yogyakarta in the slope of Mount Merapi.

Meanwhile, examples of secular buildings can be seen in the ruins of the former capital city of the Majapahit Kingdom (14th to 16th century AD) in Trowulan, East Java. The complex covers an area of 11 km x 9 km. It consists of various brick buildings, a canal ranging from 20 to 40 meters wide, purification pools, temples and iconic split gates.[64] The capital complex is currently being considered as a candidate for becoming a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Traditional Javanese buildings

Traditional Javanese buildings can be identified by their trapezoid shaped roofs supported by wooden pillars.[65] Another common feature in Javanese buildings are pendopo, pavilions with open-sides and four large pillars. The pillars and other parts of the buildings can be richly carved. This architecture style can be found at kraton, or palaces, of the Sultanates of Yogyakarta (palaces of Hamengkubuwono and Pakualaman) and Surakarta (palaces of Pakubuwono and Mangkunegaran).[66]

Traditional mosques in Java maintain a distinctive Javanese style. The pendopo model is used as the main feature of mosques as prayer halls. A trapezoidal roof is used instead of the more typically Muslim dome. These roofs are often multi-tiered and tiled.[67] In addition to not using domes, traditional Javanese mosques also often lack minarets.[68] The split gate from earlier Hindu-Buddhist period is still used in many mosques and public buildings in Java.

Some notable examples of mosques using traditional Javanese architecture include the Agung Demak Mosque, the Menara Kudus Mosque and the Great Mosque of Banten. The Kudus Mosque is also of note because it incorporates Hindu-style stone architecture.

Cuisine

.jpg.webp)

Rice is the staple crop of Javanese cuisine; a meal in Java is not considered a meal without it.[69] It is also an important part of the Javanese cultural identity, differentiating them from residents of other Indonesian islands who eat sago (for example Moluccans) and expatriates from western countries who tend more towards bread. Rice is seen as a symbol of development and prosperity, whereas tuber vegetables like cassava are associated with poverty.[70]

Javanese cuisine varies by region. Eastern Java has a preference for hot and salty foods,[70] while the Central Javanese tend to prefer sweeter foods.

A famous food in Javanese cuisine is Rujak Cingur,[71] marinated cow lips and noses served with vegetable, shrimp prawn and peanut sauce with chili. Rujak Cingur is considered a traditional food in Surabaya in East Java.

Gudeg is a traditional food from Yogyakarta[72] and Central Java which is made from young Nangka (jack fruit) boiled for several hours with palm sugar, and coconut milk.

Pecel, a type of peanut sauce with chili[73] is a common ingredient in Javanese cuisine. It is used in various types of Rujak and Gado-gado. It can also be used as stand-alone sauce with rice, prawns, eggs and vegetables as Nasi Pecel (Pecel rice).[74]

Tumpeng, is a rice served in the shape of a conical volcano,[75] usually with rice coloured yellow using turmeric. It is an important part of many ceremonies in Java. Tumpeng is served at landmark events such as birthdays, moving house, or other ceremonies.[76] Traditionally, Tumpeng is served alongside fried chicken, boiled egg, vegetables, and goat meat on a round plate made from bamboo called besek.

A notable food in Java is tempeh, a meat substitute made from soybean fermented with mould. It is a staple source of protein in Java and popular around the world as a meat substitute for vegetarians.

Names

Javanese do not usually have family names or surnames, with only a single name. Javanese names may come from traditional Javanese languages, many of which are derived from Sanskrit. Names with the prefix Su-, which means good, are very popular. After the advent of Islam, many Javanese began to use Arabic names, especially coast populations, where Islamic influences are stronger. Commoners usually only have one-word names, while nobilities use two-or-more-word names, but rarely a surname. Some people use a patronymic. Due to the influence of other cultures, many people started using names from other languages, mainly European languages. Christian Javanese usually use Latin baptism names followed by a traditional Javanese name.

Religion

| Religions | Total |

|---|---|

| Islam | 92,107,046 |

| Christianity | 2,428,121 |

| Hinduism | 160,090 |

| Buddhism | 90,465 |

| Others | 12,456 |

| Overall | 94,788,943 |

Religion of Javanese[16]

Today, most Javanese officially follow Sunni Islam as their religion,[78] first recorded instance of Islamic contact in Java is dated from 475 Hijri (1082 AD), as attested in the grave of Fatimah binti Maimun.[79]: 56 However Islamic development only became more intensive during the Majapahit period, when they traded or made tributary relations with various states like Perlak and Samudra Pasai in modern-day Aceh.[48] In the Troloyo/Tralaya cemetery of Trowulan (the capital of Majapahit), there are several Muslim tombstones with dates from the 14th century (1368 AD, 1376 AD). The close proximity of the site with the kraton means there were Muslim people in close relation with the court.[80]: 6

A minority of Javanese also follow Christianity (Protestantism and Catholicism), which are concentrated in Central Java (particularly Semarang, Surakarta, Salatiga, Magelang) and Yogyakarta for Catholicism. Native Christian churches such as the Javanese Christian Church (Gereja Kristen Jawa) and East Java Christian Church (Gereja Kristen Jawi Wetan) also exist. On a smaller scale, Hinduism and Buddhism are also found in the Javanese community. The Javanese of the Tengger tribe continue to practice Javanese-Hindu today, and live in villages on the slope of Mount Bromo.[81]

Kebatinan, also called Kejawèn,[82] Agama Jawa[83] and Kepercayaan[84] is a Javanese religious tradition, consisting of an amalgam of animistic, Hindu-Buddhist, and Islamic, especially Sufi, beliefs and practices. It is rooted in Javanese history and religiosity, syncretising aspects of different religions.

Occupations

In Indonesia, Javanese people can be found in all occupations, especially in the government and the military.

Farming

Traditionally, most Javanese people are farmers. Farming is especially common because of the fertile volcanic soil in Java. The most important agricultural commodity is rice. In 1997, it was estimated that Java produced 55% of Indonesia's total output of the crop.[85] Most farmers work in small-scale rice fields, with around 42% of farmers working and cultivating less than 0.5 hectares of land.[85] In region where soil is less fertile of where rainy season is short, other staple crops is cultivated, such as cassava.[86]

Merchant-sailor

Javanese merchants and sailors were already in frequent voyage in the seas between India and China as early as 1st century CE.[87]: 31–35 [88]: 25

Champa was assaulted by Javanese or Kunlun vessels in 774 and 787.[89][90][91] In 774 an assault was launched on Po-Nagar in Nha-trang where the pirates demolished temples, while in 787 an assault was launched on Phang-rang.[92][93][94] Several Champa coastal cities suffered naval raids and assault from Java. Java armadas was called as Javabala-sanghair-nāvāgataiḥ (fleets from Java) which are recorded in Champa epigraphs.[95][96]

The Javanese may have contacted Australia in 10th century AD, and migrated there, their settlement existing until early 1600s. According to Waharu IV inscription (931 AD) and Garaman inscription (1053 AD),[97][98] the Mataram kingdom and Airlangga's era Kahuripan kingdom (1000–1049 AD) of Java experienced a long prosperity so that it needed a lot of manpower, especially to bring crops, packings, and send them to ports. Black labor was imported from Jenggi (Zanzibar), Pujut (Australia), and Bondan (Papua).[99][100] According to Naerssen, they arrived in Java by trading (bought by merchants) or being taken prisoner during a war and then made slaves.[101] According to Chiaymasiouro, the king of Demak, in 1601 AD a subgroup of Javanese people already settled in a land called Luca Antara, which is believed to be Australia.[102] But when Eredia's servant went to Luca Antara in 1610, the land had seemingly been abandoned.[103]

The 10th century Arab account Ajayeb al-Hind (Marvels of India) gives an account of invasion in Africa by people called Wakwak or Waqwaq,[104]: 110 probably the Malay people of Srivijaya or Javanese people of Mataram kingdom,[105]: 27 [106]: 39 in 945–946 CE. They arrived in the coast of Tanganyika and Mozambique with 1000 boats and attempted to take the citadel of Qanbaloh, though eventually failed. The reason of the attack is because that place had goods suitable for their country and for China, such as ivory, tortoise shells, panther skins, and ambergris, and also because they wanted black slaves from Bantu people (called Zeng or Zenj by Arabs, Jenggi by Javanese) who were strong and make good slaves.[104]: 110 The existence of black Africans was recorded until the 15th century in Old Javanese inscriptions[107][108] and the Javanese were still recorded as exporting black slaves during the Ming dynasty era.[109]

The Malagasy people have genetic links to various Maritime Southeast Asian groups, particularly from southern Borneo.[110] Parts of the Malagasy language are sourced from the Ma'anyan language with loan words from Sanskrit, with all the local linguistic modifications via Javanese or Malay language.[111] As the Ma'anyan and Dayak people are not a sailor and were dry-rice cultivators while some Malagasy are wet rice farmers, it is likely that they are carried by the Javanese and Malay people in their trading fleets, as labor or slaves.[104]: 114–115

During the Majapahit era, almost all of the commodities from Asia were found in Java.[106]: 233–234, 239–240 This is because of extensive shipping by the Majapahit empire using various type of ships, particularly the jong, for trading to faraway places.[106]: 56–60, 286–291 Early 16th century European accounts noted the places which the Javanese merchants visited, which include Maluku Islands, Timor, Banda, Sumatra, Malacca, China, Tenasserim, Pegu (Bago), Bengal, Pulicat, Coromandel, Malabar, Cambay (Khambat), and Aden. There were also those who went to the Maldives, Calicut (Kozhikode), Oman, Aden, and the Red Sea.[112]: 191–193 [113]: 199 Ma Huan (Zheng He's translator) who visited Java in 1413, stated that ports in Java were trading goods and offer services that were more numerous and more complete than other ports in Southeast Asia.[106]: 233–234, 239–240 It was also during Majapahit era that Nusantaran exploration reached its greatest accomplishment. Ludovico di Varthema (1470–1517), in his book Itinerario de Ludouico de Varthema Bolognese stated that the Southern Javanese people sailed to "far Southern lands" up to the point they arrived at an island where a day only lasted four hours long and was "colder than in any part of the world". Modern studies have determined that such place is located at least 900 nautical miles (1666 km) south of the southernmost point of Tasmania.[114]: 248–251 When Afonso de Albuquerque conquered Malacca, the Portuguese recovered a chart from a Javanese maritime pilot, which already included part of the Americas. Regarding the chart Albuquerque said:[115]: 64 [116]: 98–99

"...a large map of a Javanese pilot, containing the Cape of Good Hope, Portugal and the land of Brazil, the Red Sea and the Sea of Persia, the Clove Islands, the navigation of the Chinese and the Gores, with their rhumbs and direct routes followed by the ships, and the hinterland, and how the kingdoms border on each other. It seems to me. Sir, that this was the best thing I have ever seen, and Your Highness will be very pleased to see it; it had the names in Javanese writing, but I had with me a Javanese who could read and write. I send this piece to Your Highness, which Francisco Rodrigues traced from the other, in which Your Highness can truly see where the Chinese and Gores come from, and the course your ships must take to the Clove Islands, and where the gold mines lie, and the islands of Java and Banda, of nutmeg and mace, and the land of the King of Siam, and also the end of the land of the navigation of the Chinese, the direction it takes, and how they do not navigate farther."

- — Letter of Albuquerque to King Manuel I of Portugal, 1 April 1512.

The Javanese people, like other Austronesian ethnicities, use a solid navigation system: Orientation at sea is carried out using a variety of different natural signs, and by using a very distinctive astronomy technique called "star path navigation". Basically, the navigators determine the bow of the ship to the islands that are recognized by using the position of rising and setting of certain stars above the horizon.[117]: 10 In the Majapahit era, compasses and magnets were used, and cartography (mapping science) was developed. In 1293 AD Raden Wijaya presented a map and census record to the Yuan Mongol invader, suggesting that mapmaking has been a formal part of governmental affair in Java.[118]: 53 The use of maps full of longitudinal and transverse lines, rhumb lines, and direct route lines traveled by ships were recorded by Europeans, to the point that the Portuguese considered the Javanese maps were the best map in the early 1500s.[114]: 249 [119]: lxxix [116][106]: 163–164, 166–168 [120]

European colonial presence diminished the range of the Javanese merchant-sailors. In 1645, Diogo do Couto noted that the Javanese had communicated with the east coast of Madagascar.[121] The decision of Amangkurat I of the Mataram Sultanate to destroy ships in coastal cities and close ports to prevent them from rebelling in the mid-17th century further reduced the Javanese people's ability in long-distance sailing.[122]: 79–80 In 1705 there is an agreement signed by VOC and Pakubuwana I of Mataram, which forbade the Javanese to sail to the east of Lombok, to the north of Kalimantan, and to the west of Lampung. In the second half of the 18th century, most of the Javanese merchant-sailors were restricted to only short-range travel.[117]: 20–21 [123]: 116–117

Shipbuilder

- Borobudur ship from Borobudur temple, 8th century AD

- Javanese jong in Banten bay, 1610

The Javanese were known to produce large ships called K'un-lun po (po of the K'un-lun people). These ships already plied the seas between India and China as early as 2nd century CE, carrying up to 1000 people alongside 250–1000 tons of cargo. The characteristics of this ship are that it is large (more than 50–60 m long), the hull is made of multiple plankings, has no outrigger, mounted with many masts and sails, the sail is in the form of a tanja sail, and has a plank fastening technique in the form of stitching with plant fibers.[124]: 27–28 [125]: 41 [126]: 275 [127]: 262 [128]: 347

Javanese trading and slaving activities in Africa caused a strong influence on boatbuilding on Madagascar and the East African coast. This is indicated by the existence of outriggers and oculi (eye ornament) on African boats.[129]: 253–288 [130]: 94

Another large ship built by the Javanese was the jong, first recorded in an Old Javanese inscription from the 9th century AD.[122]: 60 Although the characteristics may be similar, it has some differences from the po that it was using wooden dowels for joining the planks and has double passenger-to-deadweight ratio. During the Majapahit era, a jong usually carried 600–700 men with 1200–1400 tons deadweight, and was about 69.26–72.55 m LOD and 76.18–79.81 m LOA. The largest ones, carried 1000 men with 2000 tons deadweight, was about 80.51 m LOD and 88.56 m LOA.[131] The jong was mainly constructed in two major shipbuilding centres around Java: north coastal Java, especially around Rembang–Demak (along the Muria strait) and Cirebon; and the south coast of Borneo (Banjarmasin) and the adjacent islands.[132]: 33 Pegu, which is a large shipbuilding port at the 16th century, also produced jong, built by Javanese who resided there.[133]: 250

Impressed by the Javanese's skill in shipbuilding, Afonso de Albuquerque hired 60 Javanese carpenters and shipbuilders to work in India for the Portuguese. They never arrived in India, as they mutinied and took the Portuguese ship they boarded to Pasai, where they were welcomed extraordinarily.[134]: 102–103 The Dutch also realized Javanese proficiency in shipbuilding, in the 18th century, shipbuilding yards in Amsterdam employed Javanese people as the foremen.[135]: 202 The shipbuilding in Java was hampered when the VOC gained a foothold in Java starting in the early 17th century. However, in the 18th century, the Javanese shipbuilding areas (particularly Rembang and Juwana) started building large European-styled vessels (bark and brigantine type),[117]: 20 such ships may reach 400–600 tons burthen, with an average of 92 lasts (165.6–184 metric tons).[136] In 1856, John Crawfurd noted that Javanese shipbuilding activity still existed on the north coast of Java, with the shipyards supervised by Europeans, but all of the workers were Javanese. The ships that were built in the 19th century had a maximum tonnage of 50 tons and were used for river transport.[105]: 95

Blacksmith

_3.jpg.webp)

Varieties of Javanese keris

Varieties of Javanese keris

Keris of Java

Keris of Java

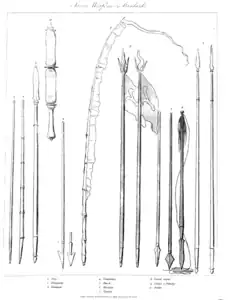

Javanese weapons and standards

Javanese weapons and standards Various keris and pole weapons of Java

Various keris and pole weapons of Java Javanese weapons: Spears, an istinggar and senapan, and a model of a cannon in its carriage.

Javanese weapons: Spears, an istinggar and senapan, and a model of a cannon in its carriage.

Blacksmiths are traditionally valued. Some blacksmiths fast and meditate to reach perfection. Javanese blacksmiths create a range of tools and farming equipment, and also cultural items such as gamelan instruments and kris.[86] The art of kris-making provided the technical skills applied to gunmaking. Cannon and firearms required special expertise and may have been made by the same individuals. The blacksmith's spiritual power was said to be transferred to the guns.[137]: 384 Majapahit under Mahapatih (prime minister) Gajah Mada (in office 1331–1364) utilized gunpowder technology obtained from Yuan dynasty for use in the naval fleet.[138]: 57 Pole gun (bedil tombak) was recorded as being used by Javanese people in 1413.[139][140]: 245

Duarte Barbosa ca. 1514 said that the inhabitants of Java are great masters in casting artillery and very good artillerymen. They make many one-pounder cannons (cetbang or rentaka), long muskets, spingarde (arquebus), schioppi (hand cannon), Greek fire, guns (cannons), and other fire-works. Every place are considered excellent in casting artillery, and in the knowledge of using it.[114]: 254 [112]: 198 [141]: 224 In 1513, the Javanese fleet led by Pati Unus, sailed to attack Portuguese Malacca "with much artillery made in Java, for the Javanese are skilled in founding and casting, and in all works in iron, exceeding what they have in India".[142]: 162 [143]: 23

Zhang Xie in Dong Xi Yang Kao (1618) mentioned that city of Palembang, which has been conquered by Javanese, produces the furious fiery oil (meng huo yu), which according to the Hua I Kao is a kind of tree secretion (shu chin), and is also called mud oil (ni yu). Zhang Xie wrote:[144]: 88

It much resemble camphor, and can corrode human flesh. When ignited and thrown on water, its light and flame become all the more intense. The barbarians use it as a fire-weapon and produce great conflagrations in which sails, bulwarks, upperworks and oars all catch fire and cannot withstand it. Fishes and tortoises coming in contact with it cannot escape from being scorched.

Because there was no mention of projector pump, the weapon is probably breakable bottles with fuses.[144]: 88

Kris knives are important items, with many heirloom kris holding significant historical value. The design of the kris is to tear apart an opponent's abdomen, making the injury more severe.

Kota Gede is famous for its silverworks and silver handicrafts.[145]

Javanese people made several types of armor such as karambalangan, kawaca, siping-siping, and waju rante. They also made steel helmets called rukuh. Armor is probably only used by high-ranking soldiers and trained/salaried troops, with salaried standing army numbering as many as 30,000 existing during the Singhasari and Majapahit era (1222 to 1527 CE), with the first mention being in the Chinese record Zhu Fan Zhi of 1225 CE. A part of the Javanese armies usually consisted of peasant levies who fought bare-chested.[106]: 320–321 [146]: 75–80 [147]: 111–113 [148]: 467 [149]

Batik making

Batik are worn by both men and women, with patterns varying to denote social stature. Batik are also used ceremonially, with certain designs used to bring good luck to a newborn infant or a newly wed couple and their families.[150][151] Some towns and villages have specialized in making batik, such as Pekalongan, Kauman, Kampung Taman and Laweyan.

Wood carving

The Javanese art of wood carving is traditionally applied to various cultural attributes such as statues, (wayang-)dolls, and masks. Woodcarving also prominent as house ornamentation and details. The elaborately carved Omah Kudus is a fine example of Javanese woodcarving mastery. The Central Java town of Jepara is famous as a center of Javanese woodcarving workshops, where artists and carpenters especially working on Javan teak wood.[152]

Javanese woodworkers making traditional masks during the Dutch East Indies era

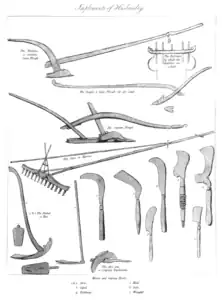

Javanese woodworkers making traditional masks during the Dutch East Indies era The carpenters' tools of the Javanese people

The carpenters' tools of the Javanese people Javanese agricultural tools

Javanese agricultural tools A drawing of Javanese manufacturing tools, handicrafts, and musical instruments

A drawing of Javanese manufacturing tools, handicrafts, and musical instruments Javanese musical instruments, many of which require the skills of blacksmith and carpenters

Javanese musical instruments, many of which require the skills of blacksmith and carpenters Javanese masks

Javanese masks

Migrations

The Javanese were probably involved in the Austronesian migration to Madagascar in the first centuries C.E. While the culture of the migration is most closely related with the Ma'anyan people of Borneo, a portion of the Malagasy language is derived from loanwords from the Javanese language.[153] It is possible that Ma'anyan people (or other indigenous people of Kalimantan closely related to the Ma'anyans) were brought as labourer and slaves by their Javanese masters in their trading fleets, which reached Madagascar by ca. 50–500 AD.[154][155][104]: 114–115

A Portuguese account described how the Javanese people already had advanced seafaring skills and had communicated with Madagascar in 1645:[121][156]: 311 [122]: 57 [157]: 51

The Javanese are all men very experienced in the art of navigation, to the point that they claim to be the most ancient of all, although many others give this honor to the Chinese, and affirm that this art was handed on from them to the Javanese. But it is certain that they formerly navigated to the Cape of Good Hope and were in communication with the east coast of the island of São Lourenço (San Laurenzo — Madagascar), where there are many brown and Javanese-like natives who say they are descended from them.

— Diogo do Couto, Decada Quarta da Asia

Since the Hindu kingdom period, Javanese merchants settled at many places in the Indonesian archipelago.[40]: 247 In the late 15th century, following the collapse of Majapahit and the rise of Muslim principalities on the northern coast of Java, many Hindu nobilities, artisans and courtiers migrated to Bali,[45] where they would contribute to the refined culture of Bali. Others who refused to convert to Islam retreated to Tengger mountain, retaining their Hindu religion and becoming the Tenggerese people.

In the conflicts during the transitions of power between the Demak, the Pajang and the Mataram in the late 16th century, some Javanese migrated to Palembang in southern Sumatra. There they established a sultanate and formed a mix of Malay and Javanese culture.[31] Palembang language is a dialect of Malay language with heavy influence of Javanese.

Declaraçam de Malaca e India Meridional com o Cathay by Manuel Godinho de Eredia (1613), described what he called India Meridional (Meridional India — Southern/South India). In his book he relates about the voyage of Chiaymasiouro (or Chiay Masiuro), king of Damuth (Demak) in Java, to a Southern land called Luca Antara (or Lucaantara, a peninsula in North Australia).[note 2][note 3] The book explained that in Meridional India already settled a subgroup of Javanese people. A brief description of this country is given in a letter written by Chiaymasiouro to the King of Pahang and in a certificate made by Pedro de Carvalhaes at Malacca on 4 October 1601.[158] In Report of Meridional India (1610) Eredia mentioned that the Javanese people of Luca Antara in all of their customs and in figure resemble the Javanese of Sunda (west Java),[note 4] only a slight difference in the language, which he described as "much the same as between the Castillian and the Portuguese". The hair extends as far as the shoulders, the tonsure resembles the tonsure of Balinese people, with a curiously curved contour.[103]

During the reign of Sultan Agung (1613–1645), some Javanese began to establish settlements in coastal West Java around Cirebon, Indramayu and Karawang. These Javanese settlements were originally commissioned by Sultan Agung as rice farming villages to support the Javanese troop logistics on his military campaign against Dutch Batavia.

The Javanese were also present in Peninsular Malaya since early times.[159] The Link between Java and Malacca was important during spread of Islam in Indonesia, when religious missionaries were sent from Malacca to seaports on the northern coast of Java.[48] Large migrations to the Malay Peninsula occurred during the colonial period, mostly from Central Java to British Malaya. Migration also took place from 1880 to 1930 from other parts of Java with a secondary migration Javanese from Sumatra and Ponorogo region in East Java.[160] Those migrations were to seek a new life away from the Dutch colonists who ruled Indonesia at that time. Today these people live throughout Peninsular Malaysia and are mainly concentrated in parts of inland, west and northwest coasts of Johor, southwest Perak, west coast of Selangor, plus cities such as Kuala Lumpur.[160]

Today, the Malaysian government classifies the descendants of these Javanese residing in Malaysia under the "Malay" label along with other native Indonesian ethnic groups which allows for socioeconomical privileges allocated for the so-called bumiputera, this assimilation is factored by integration under similar socioreligious infrastructures like mosques and intermarriage with the local Malay ethnic population in the Peninsular.[160] Many immigrants of the colonial period retain their Javanese identity, and the Javanese language is still spoken, although the younger generation in urban centers mostly has shifted to Malay.[161]

In Singapore, approximately 50–60% of its "Malay" population have some degree of Javanese ancestry, concentrated in Yishun, Ang Mo Kio, Serangoon, Sengkang and Hougang.[160] Most of them have identified themselves as "Malays", rather than Javanese.[162]

Javanese merchants were also present in the Maluku Islands as part of the spice trade. Following the Islamisation of Java, they spread Islam in the islands, with Ternate being a Muslim sultanate circa 1484.[163] Javanese merchants also converted coastal cities in Borneo to Islam.[164] The Javanese thus played an important part in transmitting Islam from the western part to the eastern part of the Archipelago with trade based from northern coast of Java.

New migration patterns emerged during colonial periods. During the rise of VOC power starting in the 17th century, many Javanese were exiled, enslaved or hired as mercenaries for the Dutch colonies of Ceylon in South Asia and the Cape colony in South Africa. These included princes and nobility who lost their dispute with the company and were exiled along with their retinues. These, along with exiles from other ethnicities like Bugis and Malay became the Sri Lankan Malay[33] and Cape Malay[34] ethnic groups respectively. Other political prisoners were transported to closer places. Prince Diponegoro and his followers were transported to North Sulawesi, following his defeat in Java War in the early 19th century. Their descendants are well known as Jaton (abbreviation of "Jawa Tondano"/Tondano Javanese).

Major migrations started during the Dutch colonial period under transmigration programs. The Dutch needed many labourers for their plantations and moved many Javanese under the program as contract workers, mostly to other parts of the colony in Sumatra. They also sent Javanese workers to Suriname in South America.[165] As of 2019, approximately 13.7% of the Suriname population is of Javanese ancestry.[10] Outside of the Dutch colonies, Javanese workers were also sent to plantations administered by the Dutch colonial government in New Caledonia, a French territory.[165]

The transmigration program that was created by the Dutch continued following independence. A significant Javanese population can be found in the Jabodetabek (Greater Jakarta) area, Lampung, South Sumatra and Jambi provinces. Several paguyuban (traditional community organisation) were formed by these Javanese immigrants, such as "Pujakesuma" (abbreviation of Indonesian: Putra Jawa Kelahiran Sumatera or Sumatra-born Javanese).

Notable people

See also

Notes

- ↑ It is very difficult to find exact figures because Malaysian census data does not consider the Javanese as one ethnicity but part of the "Malays", according to the 1950 Malaysian census it was estimated that more than 189,000 Malaysian Malays were born to Javanese parents. This figure is very significant considering the number of Malaysian Malays at that time was just under 3 million. Javanese descendants form large communities in Johor, Selangor, Perak and other states in Malaysia.[3][4][5]

- ↑ Luca antara: i.e. Nusa antara, the southern land which Eredia claims to have discovered The name Nusa antara occurs in the Pararaton, a Javanese historical work of about the 16th century. Blagden adopts Brandes' explanation that the expression Nusantara refers to the Archipelago in general. (JRASSB . No. 53. (1909). p. 144). Crawfurd says that the expression Nusa antara denoted Madura. Janssen thinks that Eredia's Luca antara was Australia or one of the islands off the north Australian coast: Hamy considers it to be Sumba. (Janssen. Malaca, Vlnde Meridionale ei le Cathay. (1882). pp, xi, xii). Major thinks it was Madura.

- ↑ According to Ferrand, the word nusa is only used in Java, Madura, and Madagascar (nusi); elsewhere, island is generally represented by the name pulaw, pulo, or some dialectical variant thereof. (Journal Asiatique. Tome XX. (1920). p. 190). Nusa may be connected, through Sanskrit, with the Greek νῆσος (nesos). It would appear that the human tongue has a tendency to corrupt an "N" into an "L" thus "Nakhon" has become "Lakhon" (Ligor) and the Malay word nuri has become lory. Linschoten's map of the Eastern Seas contains the forms Lusa (Luca) and Nusa.

- ↑ Likely what he meant here is the Cirebonese people, an Austronesian ethnic group with mixed culture of Javanese and Sundanese (heavier influence from Javanese).

References

- ↑ Pramono, S. B. (2013). Piwulang Basa Jawa Pepak. Grafindo Litera Media. ISBN 978-979-3896-38-0.

- ↑ Kewarganegaraan, Suku Bangsa, Agama, dan Bahasa Sehari-hari Penduduk Indonesia (Hasil Sensus Penduduk 2010) [Citizenship, Ethnicity, Religion, and Languages of the Indonesian Population (Results of the 2010 Population Census)] (in Indonesian), Jakarta: Central Bureau of National Statistics of the Republic of Indonesia, 2010

- ↑ "History of Javanese Migration to Malaysia" (in Indonesian). Kompas. 5 August 2022. Retrieved 3 December 2022.

- ↑ "The Javanese connection in Malaysia". MalaysiaKini. 21 November 2021. Retrieved 20 September 2022.

- ↑ A Preliminary Report on the Javanese in Selangor, Malaysia (PDF). Southeast Asian Studies, Vol. 26, No.2. 2 September 2022. Retrieved 2 December 2022.

- ↑ Kompasiana (2016). Kami Tidak Lupa Indonesia. Bentang Pustaka. ISBN 9786022910046.

- ↑ Silvey, Rachel (2005), "Transnational Islam: Indonesian Migrant Domestic Workers in Saudi Arabia", in Falah, Ghazi-Walid; Nagel, Caroline (eds.), Geographies of Muslim Women: Gender, Religion, and Space, Guilford Press, pp. 127–146, ISBN 1-57230-134-1

- ↑ "Negara yang Banyak Orang Jawa, Nomor 1 Jumlahnya Lebih dari 1,5 Juta Jiwa". Sindo.

- ↑ Milner, Anthony (2011). "Chapter 7, Multiple forms of 'Malayness'". The Malays. John Wiley & Sons. p. 197. ISBN 978-0-7748-1333-4. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

- 1 2 "Suriname". The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency. 18 December 2019. Retrieved 23 December 2019.

- ↑ Ko Oudhof, Carel Harmsen, Suzanne Loozen en Chan Choenni, "Omvang en spreiding van Surinaamse bevolkingsgroepen in Nederland Archived 18 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine" (CBS – 2011)

- ↑ Ko Oudhof en Carel Harmsen, "De maatschappelijke situatie van Surinaamse bevolkingsgroepen in Nederland Archived 18 August 2015 at the Wayback Machine" (CBS – 2011)

- ↑ Project, Joshua. "Javanese in Sri Lanka". joshuaproject.net. Retrieved 26 June 2021.

- ↑ Institut de la statistique et des études économiques de Nouvelle-Calédonie (ISEE). "Population totale, selon la communauté par commune et Province de résidence" (in French). Archived from the original (XLS) on 28 September 2007.

- ↑ "Meeting Javanese People in Thailand". UNAIRGoodNews. 12 July 2022. Retrieved 29 October 2023.

- 1 2 Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono. Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015. p. 270 (based on 2010 census data).

- ↑ Laurie Bauer, 2007, The Linguistics Student's Handbook, Edinburgh

- ↑ "Javanese". Merriam-Webster. Retrieved 1 October 2023.

- ↑ Pramono, S.B. (2013). Piwulang Basa Jawa Pepak. Grafindo Litera Media. ISBN 978-979-3896-38-0.

- ↑ Ananta, Aris; Arifin, Evi Nurvidya; Hasbullah, M. Sairi; Handayani, Nur Budi; Pramono, Agus (December 2015). Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity (in Indonesian). Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. doi:10.1355/9789814519885. ISBN 978-981-4519-87-8. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

- ↑ "Javanese language". britannica.com. Encyclopedia Britannica. 2010. Retrieved 17 March 2021.

- ↑ Thornton, David Leonard (1972). Javanization of Indonesian politics (Thesis). The University of British Columbia. doi:10.14288/1.0101705. Retrieved 7 November 2013.

- ↑ Shucker, M. A. M. (1986). Muslims of Sri Lanka: avenues to antiquity. Jamiah Naleemia Inst.

- ↑ Williams, Faldela (1988). Cape Malay Cookbook. Struik. ISBN 978-1-86825-560-3. ISBN 1-86825-560-3.

- ↑ Matusky, Patricia Ann; Sooi Beng Tan (2004). The music of Malaysia: the classical, folk, and syncretic traditions. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 107. ISBN 978-0-7546-0831-8. ISBN 0-7546-0831-X.

- ↑ Osnes, Beth (2010). The Shadow Puppet Theatre of Malaysia: A Study of Wayang Kulit with Performance Scripts and Puppet Designs. McFarland. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7864-4838-8. ISBN 0-7864-4838-5.

- ↑ "Publication Name:". Archived from the original on 10 July 2017. Retrieved 6 August 2013.

- ↑ Margaret Kleffner Nydell Understanding Arabs: A Guide For Modern Times, Intercultural Press, 2005, ISBN 1931930252, page xxiii, 14

- ↑ roughly 152 million Bengali Muslims in Bangladesh and 36.4 million Bengali Muslims in the Republic of India (CIA Factbook 2014 estimates, numbers subject to rapid population growth); about 10 million Bangladeshis in the Middle East, 1 million Bengalis in Pakistan, 5 million British Bangladeshi.

- ↑ Gandhi, Rajmohan (2013). Punjab: A History from Aurangzeb to Mountbatten. New Delhi, India, Urbana, Illinois: Aleph Book Company. p. 1. ISBN 978-93-83064-41-0.

- 1 2 Simanjuntak, Truman; Ingrid Harriet Eileen Pojoh; Muhamad Hisyam (2006). Austronesian diaspora and the ethnogeneses of people in Indonesian archipelago. Yayasan Obor Indonesia. p. 422. ISBN 978-979-26-2436-6.

- ↑ GHULAM-SARWAR YOUSOF (26 April 2013), ISSUES IN TRADITIONAL MALAYSIAN CULTURE, Partridge Singapore, pp. 107–, ISBN 978-1-4828-9540-7

- 1 2 3 Shucker, M. A. M. (1986). Muslims of Sri Lanka: avenues to antiquity. Jamiah Naleemia Inst. OCLC 15406023.

- 1 2 3 Williams, Faldela (1988). Cape Malay Cookbook. Struik. ISBN 978-1-86825-560-3.

- 1 2 Spiller, Henry (2008). Gamelan music of Indonesia. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-415-96067-0.

- ↑ Taylor (2003), p. 7.

- ↑ "Pemetaan Genetika Manusia Indonesia". Kompas.com (in Indonesian). Archived from the original on 23 February 2016. Retrieved 5 September 2017.

- ↑ Miksic, John; Marcello Tranchini; Anita Tranchini (1996). Borobudur: Golden Tales of the Buddhas. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-945971-90-0.

- ↑ Tarling, Nicholas (1999). Cambridge history of South East Asia: From early times to c.1500. Cambridge University Press. p. 203. ISBN 978-0-521-66369-4.

- 1 2 3 4 Spuler, Bertold; F.R.C. Bagley (31 December 1981). The Muslim world: a historical survey, Part 4. Brill Archive. p. 252. ISBN 978-90-04-06196-5.

- ↑ Media, Kompas Cyber (18 February 2012). "Kisah Mataram di Poros Kedu-Prambanan - Kompas.com". KOMPAS.com (in Indonesian). Retrieved 8 September 2018.

- ↑ Laguna Copperplate Inscription

- ↑ Ligor inscription

- ↑ Coedès, George (1968). Walter F. Vella, ed. The Indianized States of Southeast Asia. trans.Susan Brown Cowing. University of Hawaii Press. ISBN 978-0-8248-0368-1.

- 1 2 3 Capaldi, Liz; Joshua Eliot (2000). Bali handbook with Lombok and the Eastern Isles: the travel guide. Footprint Travel Guides. ISBN 978-0-658-01454-3.

- ↑ Sita W. Dewi (9 April 2013). "Tracing the glory of Majapahit". The Jakarta Post.

- ↑ Marshall Cavendish Corporation (2007). World and Its Peoples: Indonesia and East Timor. Marshall Cavendish. p. 1333. ISBN 978-0-7614-7643-6.

- 1 2 3 Wink, André (2004). Indo-Islamic society, 14th–15th centuries. BRILL. p. 217. ISBN 978-90-0413561-1.

- ↑ Ricklefs, M.C. (1991). A History of Modern Indonesia since c.1300, 2nd Edition. London: MacMillan. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-333-57689-6.

- ↑ Muljana, Slamet (2005). Runtuhnya kerajaan Hindu-Jawa dan timbulnya negara-negara Islam di Nusantara. Yogyakarta, Indonesia: LKiS. ISBN 979-8451-16-3.

- 1 2 Pires, Tomé (1990). The Suma oriental of Tome Pires: an account of the East. New Delhi: Asian Educational Services. ISBN 81-206-0535-7.

- ↑ Beatty, Andrew (1996). "Adam and Eve and Vishnu: Syncretism in the Javanese Slametan". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute. 2 (2): 271–288. doi:10.2307/3034096. JSTOR 3034096 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Aritonang, Jan Sihar; Steenbrink, Karel (2008). A History of Christianity in Indonesia. Brill Publishers. pp. 639–730. ISBN 9789047441830.

- ↑ Robinson, S.O. (1987). "The Terminology of Javanese Kinship". Bijdragen tot de Taal-, Land- en Volkenkunde. 143 (4): 7–12. JSTOR 27863869 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Smith-Hefner, Nancy J. (1989). "A Social History of Language Change in Highland East Java". The Journal of Asian Studies. 48 (2): 260–263. doi:10.2307/2057377. JSTOR 2057377. S2CID 163495498 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Matusky, Patricia Ann; Sooi Beng Tan (2004). The music of Malaysia: the classical, folk, and syncretic traditions. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 107. ISBN 978-0-7546-0831-8.

- ↑ Osnes, Beth (2010). The Shadow Puppet Theatre of Malaysia: A Study of Wayang Kulit with Performance Scripts and Puppet Designs. McFarland. p. 26. ISBN 978-0-7864-4838-8.

- 1 2 Robson, Stuart; Singgih Wibisono (2002). Javanese English dictionary. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7946-0000-6.

- ↑ Marr, David G.; Anthony Crothers Milner (1986). Southeast Asia in the 9th to 14th centuries. Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-9971-988-39-5.

- ↑ Errington, James Joseph (1998). Shifting languages: interaction and identity in Javanese Indonesia. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-63448-9.

- ↑ Soeseno, Ki Nardjoko (2014). Falsafah Jawa Soeharto & Jokowi. Araska. ISBN 978-602-7733-82-4.

- ↑ McDonald, Hamish (1980). Suharto's Indonesia. Melbourne: Fontana. pp. 9–10. ISBN 0-00-635721-0.

- ↑ Prambanan and Sewu Exhibition: Safeguarding a Common Heritage of Humanity, 15–24 January 2010, Bentara Budaya Jakarta 2010

- ↑ Ministry of Culture and Tourism of the Republic of Indonesia (6 October 2009). "Trowulan – Former Capital City of Majapahit Kingdom". United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) World Heritage Convention.

- ↑ Karaton Ngayogyakarta Hadiningrat (2002). Kraton Jogja: the history and cultural heritage. Kraton Yogyakarta, Indonesia Marketing Association. ISBN 978-979-969060-9.

- ↑ Eliot, Joshua; Liz Capaldi; Jane Bickersteth (2001). Indonesia handbook, Volume 3. Footprint Travel Guides. p. 303. ISBN 978-1-900949-51-4.

- ↑ Kusno, Abidin (2000). Behind the postcolonial: architecture, urban space, and political cultures in Indonesia. Routledge. p. 3. ISBN 9780415236157.

- ↑ Singh, Nagendra Kr (2002). International encyclopaedia of Islamic dynasties. Anmol Publications. p. 148. ISBN 978-81-2610403-1.

- ↑ Kalekin-Fishman, Devorah; Kelvin E. Y. Low (2010). Everyday Life in Asia: Social Perspectives on the Senses. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 52. ISBN 978-0-7546-7994-3.

- 1 2 DuFon, Margaret A.; Eton Churchill (2006). Language learners in study abroad contexts. Multilingual Matters. p. 110. ISBN 978-1-85359-851-7.

- ↑ Tania, Vania (2008). Djakabaia: Djalan-djalan dan Makan-makan. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 978-979-223923-2.

- ↑ Tempat Makan Favorit di 6 Kota. AgroMedia. 2008. p. 136. ISBN 978-979-006166-8.

- ↑ Witton, Patrick; Mark Elliott; Paul Greenway; Virginia Jealous (2003). Indonesia. Lonely Planet. p. 108. ISBN 978-1-74059-154-6.

- ↑ Soebroto, Chris (2004). Indonesia OK!!: the guide with a gentle twist. Galangpress Group. p. 72. ISBN 978-979-934179-2.

- ↑ Kim, Hyung-Jun (2006). Reformist Muslims in Yogyakarta Village: the Islamic transformation of contemporary socio-religious life. ANU E Press. p. 126. ISBN 978-1-920942-34-2.

- ↑ Owen, Sri (1999). Indonesian Regional Food and Cookery. Frances Lincoln Ltd. p. 173. ISBN 978-0-7112-1273-2.

- ↑ Aris Ananta, Evi Nurvidya Arifin, M Sairi Hasbullah, Nur Budi Handayani, Agus Pramono. Demography of Indonesia's Ethnicity. Singapore: ISEAS: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies, 2015. p. 273.

- ↑ Geertz, Clifford (1976). The religion of Java. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-28510-8.

- ↑ Sunyoto, Agus (2017). Atlas Walisongo. South Tangerang: Pustaka IIMaN.

- ↑ Manguin, Pierre-Yves; Nicholl, Robert (1985). "The Introduction of Islam into Champa". Journal of the Malaysian Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. 58 (1): 1–28.

- ↑ Beatty, Andrew (1999). Varieties of Javanese religion: an anthropological account. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-62473-2.

- ↑ Gin 2004, p. 719.

- ↑ Caldarola 1982, p. 501.

- ↑ Hooker 1988, p. 196.

- 1 2 Gérard, Françoise; François Ruf (2001). Agriculture in crisis: people, commodities and natural resources in Indonesia, 1996–2000. Routledge. p. 301. ISBN 978-0-7007-1465-0.

- 1 2 Dunham, Stanley Ann; Alice G. Dewey (2009). Surviving Against the Odds: Village Industry in Indonesia. Duke University Press. p. 50. ISBN 978-0-8223-4687-6.

- ↑ Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- ↑ Flecker, Michael (August 2015). "Early Voyaging in the South China Sea: Implications on Territorial Claims". Nalanda-Sriwijaya Center Working Paper Series. 19: 1–53.

- ↑ Tōyō Bunko (Japan) (1972). Memoirs of the Research Department. p. 6.Tōyō Bunko (Japan) (1972). Memoirs of the Research Department of the Toyo Bunko (the Oriental Library). Toyo Bunko. p. 6.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Symposium on 100 Years Development of Krakatau and Its Surroundings, Jakarta, 23–27 August 1983. Indonesian Institute of Sciences. 1985. p. 8.

- ↑ Greater India Society (1934). Journal. p. 69.

- ↑ Ralph Bernard Smith (1979). Early South East Asia: essays in archaeology, history, and historical geography. Oxford University Press. p. 447. ISBN 978-0-19-713587-7.

- ↑ Charles Alfred Fisher (1964). South-east Asia: a social, economic, and political geography. Methuen. p. 108. ISBN 9789070080600.

- ↑ Ronald Duane Renard; Mahāwitthayālai Phāyap (1986). Anuson Walter Vella. Walter F. Vella Fund, Payap University. University of Hawaii at Manoa. Center for Asian and Pacific Studies. p. 121.

- ↑ Bulletin de l'École française d'Extrême-Orient. L'Ecole. 1941. p. 263.

- ↑ Daniel George Edward Hall; Phút Tấn Nguyễn (1968). Đông Nam Á sử lược. Pacific Northwest Trading Company. p. 136.

- ↑ Nastiti (2003), in Ani Triastanti, 2007, p. 39.

- ↑ Nastiti (2003), in Ani Triastanti, 2007, p. 34.

- ↑ Nugroho (2011). p. 39.

- ↑ Nugroho (2011). p. 73.

- ↑ Kartikaningsih (1992). p. 42, in Ani Triastanti (2007), p. 34.

- ↑ de Eredia (1613). p. 63.

- 1 2 de Eredia (1613). p. 262.

- 1 2 3 4 Kumar, Ann (2012). 'Dominion Over Palm and Pine: Early Indonesia's Maritime Reach', in Geoff Wade (ed.), Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past (Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies), 101–122.

- 1 2 Lombard, Denys (2005). Nusa Jawa: Silang Budaya, Bagian 2: Jaringan Asia. Jakarta: Gramedia Pustaka Utama. An Indonesian translation of Lombard, Denys (1990). Le carrefour javanais. Essai d'histoire globale (The Javanese Crossroads: Towards a Global History) vol. 2. Paris: Éditions de l'École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Peradaban Maritim. Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN 978-602-9346-00-8.

- ↑ Maziyah, Siti (2022). "Analysing the Presence of Enslaved Black People in Ancient Java Society". Journal of Maritime Studies and National Integration. 6 (1): 62–69. doi:10.14710/jmsni.v6i1.14010. ISSN 2579-9215. S2CID 249731102.

- ↑ Jákl, Jiří (2017). "Black Africans on the maritime silk route". Indonesia and the Malay World. 45 (133): 334–351. doi:10.1080/13639811.2017.1344050. ISSN 1363-9811. S2CID 165650197.

- ↑ Shu, Yuan, ed. (2017). 中国与南海周边关系史 (History of China's Relations with the South China Sea). Beijing Book Co. Inc. ISBN 9787226051870.

一、药材:胡椒、空青、荜拨、番木鳖子、芦荟、闷虫药、没药、荜澄茄、血竭、苏木、大枫子、乌爹泥、金刚子、番红土、肉豆蔻、白豆蔻、藤竭、碗石、黄蜡、阿魏。二、香料:降香、奇南香、檀香、麻滕香、速香、龙脑香、木香、乳香、蔷薇露、黄熟香、安息香、乌香、丁皮(香)。三、珍宝:黄金、宝石、犀角、珍珠、珊瑙、象牙、龟筒、 孔雀尾、翠毛、珊瑚。四、动物:马、西马、红鹦鹉、白鹦鹉、绿鹦鹉、火鸡、白 鹿、白鹤、象、白猴、犀、神鹿(摸)、鹤顶(鸟)、五色鹦鹉、奥里羔兽。五、金 属制品:西洋铁、铁枪、锡、折铁刀、铜鼓。六、布匹:布、油红布、绞布。[4]此 外,爪哇还向明朝输入黑奴、叭喇唬船、爪哇铣、硫黄、瓷釉颜料等。爪哇朝贡贸易 输人物资不仅种类多,而且数虽可观,如洪武十五年(1382年)一次进贡的胡椒就达 七万五千斤。[5]而民间贸易显更大,据葡商Francisco de Sa记载:"万丹、雅加达等港 口每年自漳州有帆船20艘驶来装载3万奎塔尔(quiutai)的胡椒。"1奎塔尔约合59 公斤则当年从爪哇输入中国胡椒达177万公斤。

- ↑ Kusuma, Pradiptajati; Brucato, Nicolas; Cox, Murray P.; Pierron, Denis; Razafindrazaka, Harilanto; Adelaar, Alexander; Sudoyo, Herawati; Letellier, Thierry; Ricaut, François-Xavier (18 May 2016). "Contrasting Linguistic and Genetic Origins of the Asian Source Populations of Malagasy". Scientific Reports. 6 (1): 26066. Bibcode:2016NatSR...626066K. doi:10.1038/srep26066. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 4870696. PMID 27188237.

- ↑ Murray P. Cox; Michael G. Nelson; Meryanne K. Tumonggor; François-X. Ricaut; Herawati Sudoyo (2012). "A small cohort of Island Southeast Asian women founded Madagascar". Proceedings of the Royal Society B. 279 (1739): 2761–8. doi:10.1098/rspb.2012.0012. PMC 3367776. PMID 22438500.

- 1 2 Stanley, Henry Edward John (1866). A Description of the Coasts of East Africa and Malabar in the Beginning of the Sixteenth Century by Duarte Barbosa. The Hakluyt Society.

- ↑ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1993). 'The Vanishing Jong: Insular Southeast Asian Fleets in Trade and War (Fifteenth to Seventeenth Centuries)', in Anthony Reid (ed.), Southeast Asia in the Early Modern Era (Ithaca: Cornell University Press), 197–213.

- 1 2 3 Jones, John Winter (1863). The travels of Ludovico di Varthema in Egypt, Syria, Arabia Deserta and Arabia Felix, in Persia, India, and Ethiopia, A.D. 1503 to 1508. Hakluyt Society.

- ↑ Carta IX, 1 April 1512. In Pato, Raymundo Antonio de Bulhão (1884). Cartas de Affonso de Albuquerque, Seguidas de Documentos que as Elucidam tomo I (pp. 29–65). Lisboa: Typographia da Academia Real das Sciencas.

- 1 2 Olshin, Benjamin B. (1996). "A sixteenth century Portuguese report concerning an early Javanese world map". História, Ciências, Saúde-Manguinhos. 2 (3): 97–104. doi:10.1590/s0104-59701996000400005. ISSN 0104-5970. Archived from the original on 19 October 2023.

- 1 2 3 Liebner, Horst H. (2005), "Perahu-Perahu Tradisional Nusantara: Suatu Tinjauan Perkapalan dan Pelayaran", in Edi, Sedyawati (ed.), Eksplorasi Sumberdaya Budaya Maritim, Jakarta: Pusat Riset Wilayah Laut dan Sumber Daya Nonhayati, Badan Riset Kelautan dan Perikanan; Pusat Penelitian Kemasyarakatan dan Budaya, Universitas Indonesia, pp. 53–124

- ↑ Suarez, Thomas (2012). Early Mapping of Southeast Asia: The Epic Story of Seafarers, Adventurers, and Cartographers Who First Mapped the Regions Between China and India. Tuttle Publishing.

- ↑ Cortesão, Armando (1944). The Suma oriental of Tomé Pires : an account of the East, from the Red Sea to Japan, written in Malacca and India in 1512–1515 ; and, the book of Francisco Rodrigues, rutter of a voyage in the Red Sea, nautical rules, almanack and maps, written and drawn in the East before 1515 volume I. London: The Hakluyt Society. ISBN 9784000085052.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ "Majapahit-era Technologies". Nusantara Review. 2 October 2018. Retrieved 11 June 2020.

- 1 2 Couto, Diogo do (1645). Da Ásia: Década Quarta. Lisbon: Regia Officina Typografica, 1778–1788. Reprint, Lisbon, 1974. Década IV, part iii, p. 169.

- 1 2 3 Reid, Anthony (2000). Charting the Shape of Early Modern Southeast Asia. Silkworm Books. ISBN 9747551063.

- ↑ Ricklefs, Merle Calvin (2008). A History of Modern Indonesia Since c. 1200 Fourth Edition (E-Book version) (4th ed.). New York: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9780230546851.

- ↑ Dick-Read, Robert (July 2006). "Indonesia and Africa: questioning the origins of some of Africa's most famous icons". The Journal for Transdisciplinary Research in Southern Africa. 2 (1): 23–45. doi:10.4102/td.v2i1.307.

- ↑ Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- ↑ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (September 1980). "The Southeast Asian Ship: An Historical Approach". Journal of Southeast Asian Studies. 11 (2): 266–276. doi:10.1017/S002246340000446X. JSTOR 20070359. S2CID 162220129.

- ↑ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1993). "Trading Ships of the South China Sea. Shipbuilding Techniques and Their Role in the History of the Development of Asian Trade Networks". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient: 253–280.

- ↑ Christie, Anthony (1957). "An Obscure Passage from the "Periplus: ΚΟΛΑΝΔΙΟϕΩΝΤΑ ΤΑ ΜΕΓΙΣΤΑ"". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. 19: 345–353. doi:10.1017/S0041977X00133105. S2CID 162840685 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ Hornell, James (1946). Water Transport: Origins & Early Evolution. Newton Abbot: David & Charles. ISBN 9780715348604. OCLC 250356881.

- ↑ Dick-Read, Robert (2005). The Phantom Voyagers: Evidence of Indonesian Settlement in Africa in Ancient Times. Thurlton.

- ↑ Averoes, Muhammad (2022). "Re-Estimating the Size of Javanese Jong Ship". HISTORIA: Jurnal Pendidik Dan Peneliti Sejarah. 5 (1): 57–64. doi:10.17509/historia.v5i1.39181. S2CID 247335671.

- ↑ Tarling, Nicholas (1999). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521663700.

- ↑ Cortesão, Armando (1944). The Suma oriental of Tomé Pires : an account of the East, from the Red Sea to Japan, written in Malacca and India in 1512–1515 ; and, the book of Francisco Rodrigues, rutter of a voyage in the Red Sea, nautical rules, almanack and maps, written and drawn in the East before 1515 volume II. London: The Hakluyt Society.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain. - ↑ Reid, Anthony (1988). Southeast Asia in the Age of Commerce, 1450–1680. Volume One: The Lands Below the Winds. Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300039214.

- ↑ Unger, Richard W. (2013). "Chapter Five: The Technology and Teaching of Shipbuilding 1300-1800". Technology, Skills and the Pre-Modern Economy in the East and the West. BRILL. ISBN 9789004251571.

- ↑ Lee, Kam Hing (1986): 'The Shipping Lists of Dutch Melaka: A Source for the Study of Coastal Trade and Shipping in the Malay Peninsula During the 17th and 18th Centuries', in Mohd. Y. Hashim (ed.), Ships and Sunken Treasure (Kuala Lumpur: Persatuan Muzium Malaysia), 53–76.

- ↑ Tarling, Nicholas (1992). The Cambridge History of Southeast Asia: Volume 1, From Early Times to C.1800. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 9780521355056.

- ↑ Pramono, Djoko (2005). Budaya Bahari. Gramedia Pustaka Utama. ISBN 9789792213768.

- ↑ Mayers (1876). "Chinese explorations of the Indian Ocean during the fifteenth century". The China Review. IV: p. 178.

- ↑ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (1976). "L'Artillerie legere nousantarienne: A propos de six canons conserves dans des collections portugaises" (PDF). Arts Asiatiques. 32: 233–268. doi:10.3406/arasi.1976.1103. S2CID 191565174.

- ↑ Partington, J. R. (1999). A History of Greek Fire and Gunpowder. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0-8018-5954-0.

- ↑ Wade, Geoff; Tana, Li, eds. (2012). Anthony Reid and the Study of the Southeast Asian Past. Singapore: Institute of Southeast Asian Studies. ISBN 978-981-4311-96-0.

- ↑ Crawfurd, John (1856). A Descriptive Dictionary of the Indian Islands and Adjacent Countries. Bradbury and Evans.

- 1 2 Needham, Joseph (1986). Science and Civilisation in China, Volume 5: Chemistry and Chemical Technology, Part 7, Military Technology: The Gunpowder Epic. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- ↑ Tadié, J (1998), Guillaud, Dominique; Seysset, M.; Walter, Annie (eds.), Kota Gede : le devenir identitaire d'un quartier périphérique historique de Yogyakarta (Indonésie); Le voyage inachevé... à Joël Bonnemaison, ORSTOM, retrieved 20 April 2012

- ↑ Jákl, Jiří (2014). Literary Representations of War and Warfare in Old Javanese Kakawin Poetry (PhD thesis). The University of Queensland.

- ↑ Oktorino, Nino (2020). Hikayat Majapahit – Kebangkitan dan Keruntuhan Kerajaan Terbesar di Nusantara. Jakarta: Elex Media Komputindo. ISBN 978-623-00-1741-4.

- ↑ Miksic, John N.; Goh, Geok Yian (2017). Ancient Southeast Asia. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Yang, Shao-yun (15 June 2020). "A Chinese Gazetteer of Foreign Lands: A new translation of Part 1 of the Zhufan zhi 諸蕃志 (1225)". Storymaps. Retrieved 19 October 2023.

- ↑ Stephenson, Nina (1993). "The Past, Present, and Future of Javanese Batik: A Bibliographic Essay". Art Documentation: Journal of the Art Libraries Society of North America. 12 (3): 107–113. doi:10.1086/adx.12.3.27948560. JSTOR 27948560. S2CID 163835838 – via JSTOR.

- ↑ "UNESCO - Indonesian Batik". ich.unesco.org. Retrieved 15 May 2022.

- ↑ "In a Central Java town, local wood enterprises carve a niche in the global market – CIFOR Forests News". CIFOR Forests News. 6 March 2018. Retrieved 1 June 2018.

- ↑ Adelaar, Alexander (2006). The Indonesian migrations to Madagascar: making sense of the multidisciplinary evidence. Melbourne Institute of Asian Languages and Societies, The University of Melbourne. ISBN 9789792624366.

- ↑ Dewar, Robert E.; Wright, Henry T. (1993). "The culture history of Madagascar". Journal of World Prehistory. 7 (4): 417–466. doi:10.1007/bf00997802. hdl:2027.42/45256. S2CID 21753825.

- ↑ Burney DA, Burney LP, Godfrey LR, Jungers WL, Goodman SM, Wright HT, Jull AJ (August 2004). "A chronology for late prehistoric Madagascar". Journal of Human Evolution. 47 (1–2): 25–63. doi:10.1016/j.jhevol.2004.05.005. PMID 15288523.

- ↑ Hornell, James (December 1934). "Indonesian Influence on East African Culture". The Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute of Great Britain and Ireland. 64: 305–332. doi:10.2307/2843812. JSTOR 2843812.

- ↑ Manguin, Pierre-Yves (2016). "Austronesian Shipping in the Indian Ocean: From Outrigger Boats to Trading Ships". In Campbell, Gwyn (ed.). Early Exchange between Africa and the Wider Indian Ocean World. Palgrave Macmillan. pp. 51–76. ISBN 9783319338224.

- ↑ Mills (1930). p. 3.

- ↑ Crawfurd, John (1856). A descriptive dictionary of the Indian islands & adjacent countries. Bradbury & Evans. pp. 244.

- 1 2 3 4 Linda Sunarti; Teuku Reza Fadeli (2018). "Tracing Javanese Identity And Culture In Malaysia Asimilation And Adaptation Of Javanese In Malaysia". Paramita: Historical Studies Journal. 28 (1): 52–4. doi:10.15294/paramita.v28i1.10923. ISSN 0854-0039.

- ↑ Miyazaki, Koji (2000). "Javanese-Malay: Between Adaptation and Alienation". Sojourn: Journal of Social Issues in Southeast Asia. 15 (1): 76–99. doi:10.1355/SJ15-1D. JSTOR 41057030. P. 83: "Generally speaking, however, as one might expect, younger Javanese-Malays can hardly understand Javanese and are Malay monolingual".

- ↑ LePoer, Barbara Leitch (1991). Singapore, a country study. Federal Research Division, Library of Congress. p. 83. ISBN 9780160342646. Retrieved 17 February 2013.

Singapore Malay community leaders estimated that some 50 to 60 percent of the community traced their origins to Java and an additional 15 to 20 percent to Bawean Island, in the Java Sea north of the city of Surabaya.

- ↑ Storch, Tanya (2006). Religions and missionaries around the Pacific, 1500–1900. Ashgate Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7546-0667-3.

- ↑ Lapidus, Ira Marvin (2002). A history of Islamic societies. Cambridge University Press. p. 384. ISBN 978-0-521-77933-3.

- 1 2 Martinez, J.T; Vickers, A.H (2012). "Indonesians overseas – deep histories and the view from below". Indonesia and the Malay World. 40 (117): 111–121. doi:10.1080/13639811.2012.683667. S2CID 161553591. Retrieved 28 December 2019.

Sources

- Caldarola, Carlo (1982), Religion and Societies: Asia and the Middle East, Walter de Gruyter

- Gin, Ooi Keat (2004), Southeast Asia: A Historical Encyclopedia, from Angkor Wat to Timor. R-Z. Volume three, ABC-CLIO

- Hooker, M.B. (1988), Islam in South East Asia, Brill

Further reading

- de Eredia, Manuel Godinho (1613). Description of Malacca and Meridional India. Translated from the Portuguese with notes by J. V. Mills in Eredia's Description of Malaca, Meridional India, and Cathay, Journal of the Malayan Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society. Vol. VIII, April 1930.

- Kuncaraningrat Raden Mas; Southeast Asian Studies Program (Institute of Southeast Asian Studies) (1985), Javanese culture, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-582542-8

- Nugroho, Irawan Djoko (2011). Majapahit Peradaban Maritim. Suluh Nuswantara Bakti. ISBN 9786029346008.

- Triastanti, Ani. Perdagangan Internasional pada Masa Jawa Kuno; Tinjauan Terhadap Data Tertulis Abad X–XII. Essay of Faculty of Cultural Studies. Gadjah Mada University of Yogyakarta, 2007.

.png.webp)