Richard B. Hubbard | |

|---|---|

| |

| United States Minister to Japan | |

| In office July 2, 1885 – May 15, 1889 | |

| President | Grover Cleveland |

| Preceded by | John Bingham |

| Succeeded by | John Franklin Swift |

| 16th Governor of Texas | |

| In office December 1, 1876 – January 21, 1879 | |

| Lieutenant | Vacant |

| Preceded by | Richard Coke |

| Succeeded by | Oran Milo Roberts |

| 11th Lieutenant Governor of Texas | |

| In office January 15, 1874 – December 1, 1876 | |

| Governor | Richard Coke |

| Preceded by | Vacant |

| Succeeded by | Joseph D. Sayers |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Richard Bennett Hubbard Jr. November 1, 1832 Walton County, Georgia, U.S. |

| Died | July 12, 1901 (aged 68) Tyler, Texas, U.S. |

| Resting place | Oakwood Cemetery, Tyler |

| Political party | Democratic |

| Spouses | Eliza B. Hudson

(m. 1858; died 1868)Janie Roberts

(m. 1869; died 1887) |

| Alma mater | Harvard University (LLB) |

| Military service | |

| Allegiance | Confederate States |

| Branch/service | Confederate States Army |

| Years of service | 1861–1865 |

| Rank | Colonel |

| Commands | 5th Texas Infantry Battalion 22nd Texas Infantry Regiment 1st Brigade, Greyhound Division |

| Battles/wars | American Civil War |

.jpg.webp)

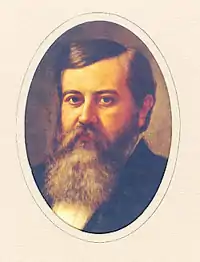

Richard Bennett Hubbard Jr. (November 1, 1832 – July 12, 1901), occasionally referred to by the nickname Jumbo,[1][2] was the 16th governor of Texas from 1876 to 1879 and United States Envoy to Japan from 1885 to 1889. He was a Confederate veteran of the American Civil War and was a member of the Democratic Party.

Early years

Hubbard was the son of Richard Bennett and Serena (Carter) Hubbard. He was born in Walton County, Georgia, but spent his formative years in Jasper County, Georgia. In 1851, Hubbard graduated from Mercer Institute with an A.B. degree in literature. He was elected National University Orator, a high honor at Mercer. Hubbard then briefly attended lectures at the University of Virginia. In 1853, Hubbard graduated from Harvard University with an LL.B. degree. After graduating from Harvard, Hubbard and his parents moved to Smith County, Texas. They settled in Tyler, Texas and then on a plantation near Lindale, Texas. Hubbard first entered politics in 1855 as an opponent of the American Know Nothing Party. In the 1856 presidential election, Hubbard supported James Buchanan, who appointed him United States Attorney for the western district of Texas. Hubbard resigned in 1859 to run for the Texas legislature. He was elected and became a supporter of Southern secession.[3]

Civil War

After secession, Hubbard ran unsuccessfully for a seat in the Congress of the Confederate States. Then he started recruiting a unit that would become the 5th (Hubbard's) Texas Infantry Battalion, serving as the commanding officer. Despite difficulties in recruiting infantry in Texas, the battalion became integrated into a regiment in March 1862; and Hubbard became the major of the 22nd Texas Infantry. He was promoted to lieutenant colonel in May and became the commanding full colonel on June 17, 1862. Staying in the Trans-Mississippi Department the 22nd was transferred to Arkansas, where it was grouped into the 1st Brigade of Walker's Greyhounds, a division made up solely of units from Texas under command of Maj. Gen. John George Walker. Hubbard fought in the Battle of Young's Point. After serving on a military court, Hubbard returned to his regiment in time to participate in the Red River Campaign. Afterwards, he fought at Jenkin's Ferry. In February 1865, back in Texas, Hubbard was appointed commander of the 1st Brigade. He was finally paroled on July 12, 1865.[3]

Politics

Hubbard's postwar law practice, supplemented by income from real estate and railroad promotion, enabled him to resume his political career by 1872, when he was chosen presidential elector on the Horace Greeley ticket. Hubbard was subsequently elected Lieutenant Governor of Texas in 1873 and 1876 and succeeded to the governorship on December 1, 1876 when Richard Coke resigned to become a United States Senator.[3]

Hubbard's gubernatorial term was marked by post-Reconstruction financial difficulties, by general lawlessness, and by the fact that the legislature was never in session during his administration. Though political opponents prevented his nomination for a second term, he remained popular with the people of Texas. His accomplishments as governor include reducing the public debt, fighting land fraud, promoting educational reforms, and restoring public control of the state prison system.

In 1884, Hubbard served as temporary chairman of the Democratic national nominating convention. He supported the party nominee, Grover Cleveland, and was appointed Minister to Japan in 1885 after Cleveland won the presidency. Hubbard's four years in Japan marked a delicate transitional period in Japanese-American relations. Japan was emerging from feudalism and dependency and had begun to insist on recognition as a diplomatic equal, a position Hubbard strongly supported. He concluded with Japan an extradition treaty, and his preliminary work on the general treaty revisions provided the basis for the revised treaties of 1894–99. When he returned to the United States in 1889, he wrote a book based upon his diplomatic experience, The United States in the Far East, which was published in 1899.[3]

Personal

Hubbard was a Baptist, a Freemason, and a member of the Board of Directors of Texas A&M University. In 1876 he was chosen Centennial Orator of Texas to represent the state at the World's Exposition in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. There he urged national unity and goodwill in an acclaimed oration.

Hubbard was first married to Eliza B. Hudson, daughter of Dr. G. C. Hudson of LaFayette, Alabama, on November 30, 1858; one daughter of this marriage, Serena, survived. Hubbard's second marriage, on November 26, 1869, was to Janie Roberts, daughter of Willis Roberts of Tyler. Janie died during Hubbard's mission to Japan, leaving him a second daughter, Searcy. Hubbard lived his final years in Tyler, where he died on July 12, 1901. He is buried in Oakwood Cemetery, Tyler.

Hubbard in Hill County is named for him.

References

- ↑ Utley 2002, chapter 9.

- ↑ Clavin 2023, p. 331.

- 1 2 3 4 Trimpi 2010, pp. 121–122.

Sources

- Clavin, Tom (2023). Follow Me to Hell: McNelly's Texas Rangers and the Rise of Frontier Justice. New York, New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 978-1-250-21455-3.

- Trimpi, Helen P. (2010). Crimson Confederates: Harvard Men who Fought for the South. Knoxville, TN: University of Tennessee Press. ISBN 978-1-5723-3682-7.

- Utley, Robert M. (2002). Lone Star Justice: The First Century of the Texas Rangers. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-199-92371-7.

External links

- Richard Bennett Hubbard, Jr. from the Handbook of Texas Online

- Entry for Richard B. Hubbard from the Biographical Encyclopedia of Texas published 1880, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Sketch of Richard B. Hubbard from A pictorial history of Texas, from the earliest visits of European adventurers, to A.D. 1879, hosted by the Portal to Texas History.

- Jack L. Hammersmith, Spoilsmen in a "Flowry Fairyland:" The Development of the U.S Legation in Japan 1859–1906 (Kent, OH: The Kent State University Press, 1998)

- Wardlaw, Trevor P. "Sires and Sons: The Story of Hubbard's Regiment." CreateSpace Independent Publishing Platform, 2015. ISBN 978-1511963732