Richard Bellingham | |

|---|---|

| |

| 8th, 16th, and 18th Governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony | |

| In office 1641–1642 | |

| Monarch | Charles I |

| Preceded by | Thomas Dudley |

| Succeeded by | John Winthrop |

| In office 1654–1655 | |

| Monarch | The Protectorate |

| Preceded by | John Endecott |

| Succeeded by | John Endecott |

| In office 1665–1672 | |

| Monarch | Charles II |

| Preceded by | John Endecott |

| Succeeded by | John Leverett |

| Personal details | |

| Born | c. 1592 Boston, Lincolnshire, England |

| Died | 7 December 1672 (aged 79–80) Boston, Massachusetts Bay Colony |

| Signature | |

Richard Bellingham (c. 1592 – 7 December 1672) was a colonial magistrate, lawyer, and several-time governor of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, and the last surviving signatory of the colonial charter at his death. A wealthy lawyer in Lincolnshire prior to his departure for the New World in 1634, he was a liberal political opponent of the moderate John Winthrop, arguing for expansive views on suffrage and lawmaking, but also religiously somewhat conservative, opposing (at times quite harshly) the efforts of Quakers and Baptists to settle in the colony. He was one of the architects of the Massachusetts Body of Liberties, a document embodying many sentiments also found in the United States Bill of Rights.

Although he was generally in the minority during his early years in the colony, he served ten years as colonial governor, most of them during the delicate years of the English Restoration, when King Charles II scrutinized the behavior of the colonial governments. Bellingham notably refused a direct order from the king to appear in England, an action that may have contributed to the eventual revocation of the colonial charter in 1684.

He was twice married, survived by his second wife and his only son Samuel. He died in 1672, leaving an estate in present-day Chelsea, Massachusetts, and a large house in Boston. The estate became embroiled in legal action lasting more than 100 years after his will was challenged by his son and eventually set aside. Bellingham is immortalized in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter and Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The New England Tragedies, both of which fictionalize events from colonial days.

Early life

Richard Bellingham, the son of William Bellingham and Frances Amcotts, was born in Lincolnshire, England, in about 1592. The family was apparently well to do; they resided in a manor at Bromby Wood near Scunthorpe.[1][2] He studied law at Brasenose College, Oxford, matriculating on 1 December 1609.[3] In 1625 he was elected Recorder (the highest community legal post) of Boston, a position he held until 1633. He represented Boston as a member of Parliament in 1628 and 1629.[4] He was first married to Elizabeth Backhouse of Swallowfield, Berkshire, with whom he had a number of children, although only their son Samuel survived to adulthood.[5]

In 1628 he became an investor in the Massachusetts Bay Company, and was one of the signers of the land grant issued to it by the Plymouth Council for New England. His name also appears on the royal charter issued for the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1629.[6] In 1633 he resigned as recorder of Boston and began selling off his properties. The next year he sailed for the New World with his wife and son;[7] Elizabeth died not long after their arrival in Boston, Massachusetts.[8]

Massachusetts Bay Colony

Bellingham immediately assumed a prominent role in the colony, serving on the committee that oversaw the affairs of Boston (a precursor to the board of selectmen). In this role he participated in the division of community lands that included the establishment of Boston Common.[9] Not long after his arrival, he purchased the ferry service between Boston and Winnessimmett (present-day Chelsea) from Samuel Maverick, along with tracts of land that encompass much of Chelsea. In addition to his mansion house in Boston, he also established a country home near the ferry in Winnessimmett.[10] A house he built in 1659 still stands in Chelsea, and is known as the Bellingham-Cary House.[11]

For many years he was elected to the colony's council of assistants, which advised the governor on legislative matters and served as a judicial body, and he also served several terms as colonial treasurer. He was first elected deputy governor of the colony in 1635, at a time when the dominant John Winthrop was out of favor, and was elected to the post again in 1640.[12] In 1637, during the Antinomian Controversy, he was one of the magistrates that sat during the trial of Anne Hutchinson, and voted for her to be banished from the colony.[13] According to historian Francis Bremer, Bellingham was somewhat brash and antagonistic, and he and Winthrop repeatedly clashed on political matters.[14] During these early years Bellingham was chosen to be on the first board of overseers of Harvard College.[15] He also contributed to the development of the colony's first legal code, known as the Massachusetts Body of Liberties.[16] This work was opposed and repeatedly stalled by Winthrop, who favored a common law approach to legislation.[17]

In 1641 Bellingham was elected governor for the first time, running against Winthrop.[18] The Body of Liberties was formally adopted during his term.[17] However, he served for just one year, and was replaced by Winthrop in 1642.[18] Bellingham's defeat may have been caused in part by the scandalous impropriety surrounding his second marriage. A friend who was a guest in his house had been courting Penelope Pelham, a young woman of twenty. According to Winthrop, Bellingham, now 50 and a widower, won her heart, and, without waiting for the formalities of the banns of marriage, officiated at his own wedding. When the issue came before the colonial magistrates, Bellingham (as the governor and chief magistrate) refused to step down from the bench to face the charges, thus bringing the matter to a somewhat awkward end.[19] Bellingham's term in office was characterized by Winthrop as extremely difficult: "The General Court was full of uncomfortable agitations and contentions by reason of Bellingham's unfriendliness to some other magistrates. He set himself in an opposite frame to them in all proceedings, which did much to retard business".[20]

In the 1640s constitutional issues concerning the power of the assistants arose. In a case involving an escaped pig, the assistants ruled in favor of a merchant who had allegedly taken a widow's errant animal. She appealed to the general court, which ruled in her favor. The assistants then asserted their right to veto the general court's decision, sparking the controversy. John Winthrop argued that the assistants, as experienced magistrates, must be able to check the democratic institution of the general court, because "a democracy is, amongst most civil nations, accounted the meanest and worst of all forms of government."[21] Bellingham was one of only two assistants (the other was Richard Saltonstall) who opposed the final decision that the assistants' veto should stand.[22] Bellingham and Saltonstall were often in a minority that opposed the more conservative views of Winthrop and Thomas Dudley.[23] In 1648 Bellingham sat on a committee established to demonstrate that the colony's legal codes were not "repugnant to the laws of England", as called for by the colonial charter.[24]

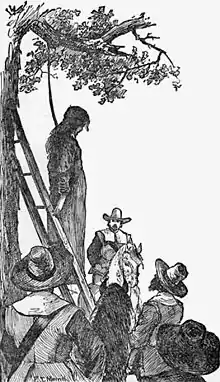

In 1650, when Bellingham was an assistant, he concurred in the judicial decision banning William Pynchon's The Meritorious Price of Our Redemption, which expressed views many Puritans considered heretical.[25] Bellingham was again elected governor in 1654, and again in May 1665 after the death of Governor John Endecott.[26] He was thereafter annually re-elected to the post until his death, ultimately serving a total of ten years as governor and thirteen as deputy governor.[27] While he was deputy to Endecott in 1656, a boat carrying several Quakers arrived in Boston. Since Endecott was in Salem at the time, Bellingham directed the government's reaction to their arrival. Because Quakerism was anathema to the Puritans, the Quakers were confined to the ship, their belongings were searched, and books promoting their religion were destroyed. After five weeks of captivity, they were sent back to England.[28] During Endecott's administration the penalties for Quakers defying banishment from the colony were made progressively harsher, until they included the imposition of the death penalty for repeat offenders. Under these laws, four Quakers were put to death for returning to the colony after their banishment.[29] Quaker historians have also been harsh in their assessments of Bellingham.[30] After Massachusetts authorities agreed that the death penalty did not work (it had long term negative consequences, feeding perceptions of Massachusetts intransigence), the law was modified to reduce the penalties to branding and whipping.[31][32]

English Restoration

The 1640s and 1650s in England were a time of great turmoil. The English Civil War led to the establishment of the Commonwealth of England and eventually the Protectorate of Oliver Cromwell.[33] In this period, Massachusetts was generally sympathetic to Cromwell and the Parliamentary cause.[34] With the restoration of Charles II to the throne in 1660, all of the colonies, and Massachusetts in particular, came under his scrutiny. In 1661 he issued a mandamus forbidding further persecution of the Quakers.[35] He also requested specific changes to be made to Massachusetts laws to increase suffrage and tolerance for other Protestant religious practices, actions that were resisted or ignored during the Endecott administration.[36] Charles finally sent royal commissioners to New England in 1664 to enforce his demands, but Massachusetts, of all the New England colonies, was the most recalcitrant, refusing all of the substantive demands or enacting changes that only superficially addressed the issues.[37]

The reaction by Charles to this was to issue an order in 1666 demanding that Bellingham, since he was then governor, and William Hathorne, the speaker of the general court, travel to England to answer for the colony's behavior.[39] The issue of how to answer this demand divided the colony, with petitions from a cross-section of the colony's population calling for the magistrates to obey the king's demand.[40] The debate also introduced a long-term rift in the council of assistants between hardliners wanting to resist the king's demands at all costs and moderates who thought the king's demands should be accommodated.[41] Bellingham sided with the hardliners and the decision was reached to send the king a letter. The letter questioned whether the request actually originated with the king, protested that the colony was loyal to him, and claimed the magistrates had already explained fully why they were unable to comply with the king's demands.[42] The magistrates further pacified the angered sovereign by sending over a ship full of masts as a gift (New England was a valuable source of timber for the Royal Navy).[39] Distracted by the war with the Dutch and domestic politics, Charles did not pursue the issue further until after Bellingham's death, though for numerous reasons the Massachusetts Bay Colony charter was finally voided in 1684.[42][43]

Death and legacy

Richard Bellingham died on 7 December 1672. He was the last surviving signer of the colonial charter, and was buried in Boston's Granary Burying Ground.[44] He was survived by his son Samuel from his first marriage and his second wife Penelope, who outlived him by 30 years.[45] His landholdings at Winnessimmett became tied up in legal action lasting more than 100 years, and involved court and procedural decisions on both sides of the Atlantic to resolve.[46] Under the terms of his will, some of his properties in Winnessimmett were set aside for religious uses. His son challenged the will, which was eventually set aside. The litigation continued, carried on by his heirs and succeeding owners and occupants of the properties, and was finally concluded in 1785.[47] The town of Bellingham, Massachusetts is named in his honor,[48] and a number of features in Chelsea, including a square, a street, and a hill, bear the name Bellingham.[49]

Bellingham was immortalized as a fictional character in Nathaniel Hawthorne's The Scarlet Letter, as the brother of Ann Hibbins, a woman who was executed (in real life in 1656, as well as in the book) for practicing witchcraft.[50] There are apparently no contemporary references to Mrs. Hibbins as Bellingham's sister—Hawthorne's formation of this connection appears to be based on a footnote in James Savage's 1825 edition of John Winthrop's journals,[51] and a genealogical tree of the Bellinghams published early in the 20th century does not mention her.[52] However, Ann Hibbins' second husband, William Hibbins, was first married to Richard Bellingham's sister Hester[53][54] but she died a year later and was buried in England.[54][55] Bellingham also appears in Henry Wadsworth Longfellow's The New England Tragedies, which fictionalizes events dealing with the Quakers.[56]

Notes

- ↑ Anderson, p. 1:246

- ↑ Larken, p. 16

- ↑ Anderson, p. 1:243

- ↑ Addison, p. 108

- ↑ Anderson, p. 1:247

- ↑ Morison, p. 34

- ↑ Goss, p. 262

- ↑ Moore, p. 335

- ↑ Goss, p. 263

- ↑ Watts et al, pp. 294–295,305

- ↑ "17th century history of the Bellingham-Cary House". The Governor Bellingham-Cary House Association. Retrieved 1 March 2011.

- ↑ Moore, pp. 335–336

- ↑ Battis, p. 190

- ↑ Bremer, p. 243

- ↑ Morison, p. 189

- ↑ Morison, pp. 226–229

- 1 2 Bremer, p. 305

- 1 2 Moore, pp. 336–337

- ↑ Moore, p. 339

- ↑ Partridge, p. 7

- ↑ Morison, p. 92

- ↑ Morison, p. 93

- ↑ Moore, p. 340

- ↑ Bremer, pp. 305, 376

- ↑ Morison, p. 372

- ↑ Bridgeman, pp. 44–45

- ↑ Whitmore, pp. 16–17

- ↑ Partridge, p. 9

- ↑ Moore, p. 357

- ↑ Goss, p. 264

- ↑ Palfrey, p. 2:482

- ↑ Moore, p. 383

- ↑ Moore, pp. 323–328

- ↑ Bremer, p. 335

- ↑ Moore, p. 162

- ↑ Hart, p. 484

- ↑ Hart, p. 485

- ↑ Hayes, pp. 292–292

- 1 2 Partridge, p. 11

- ↑ Bliss, p. 158

- ↑ Doyle, pp. 150–151

- 1 2 Doyle, p. 151

- ↑ Hart, pp. 565–566

- ↑ Moore, p. 345

- ↑ Moore, p. 346

- ↑ Watts et al, p. 393

- ↑ These disputes are documented in detail in Watts et al, pp. 420ff

- ↑ Partridge, p. 1

- ↑ See Clarke and Clark for details.

- ↑ Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, p. 186

- ↑ Ryskamp, p. 267

- ↑ Larken, p. 118

- ↑ Married 4 March 1632/3 Boston, Lincolnshire (PR)

- 1 2 Devey, Gerald (1950). The Hibbins Family of Weo & Rowton in the Parish of Stokesay, Shropshire, with Descendants & Related Families. Society of Genealogists, London.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ↑ Buried 3 Sep 1634 Stokesay, Shropshire (PR)

- ↑ Longfellow, pp. 5–95

References

- Addison, Albert (1912). The Romantic History of the Puritan Fathers. Boston: L. C. Page. OCLC 1074942.

- Anderson, Robert C.; Sanborn, George F. Jr.; Sanborn, Melinde L. (1999). The Great Migration, Immigrants to New England 1634–1635. Vol. I A–B. Boston: New England Historic Genealogical Society. ISBN 0-88082-110-8. OCLC 49260702.

- Battis, Emery (1962). Saints and Sectaries: Anne Hutchinson and the Antinomian Controversy in the Massachusetts Bay Colony. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

- Bremer, Francis (2003). John Winthrop: America's Forgotten Founder. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514913-5. OCLC 237802295.

- Bridgeman, Thomas (1856). The Pilgrims of Boston and their Descendants. New York: D. Appleton and Company.

- Clarke, Harriman; Clark, Peggy (2003). Chelsea. Charleston, SC: Arcadia Press. ISBN 978-0-7524-1208-5. OCLC 40687386.

- Doyle, John Andrew (1887). English Colonies in America, Volume 3. New York: Henry Holt. OCLC 2453886.

- Goss, E. H (March 1885). "About Richard Bellingham". The Magazine of American History with Notes and Queries. Vol. 13, no. 3. New York: A. S. Barnes. OCLC 1590082.

- Hart, Albert Bushnell, ed. (1927). Commonwealth History of Massachusetts. New York: The States History Company. OCLC 1543273.

- Hayes, John, ed. (1992). British Paintings of the Sixteenth Through Nineteenth Centuries. Washington, DC: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-41066-3. OCLC 185323723.

- Larken, Arthur Staunton (1902). Lincolnshire Pedigrees, Volume 1. London: Harleian Society. OCLC 1751768.

- Longfellow, Henry Wadsworth (1868). The New-England Tragedies. Ticknor and Fields. OCLC 276678.

- Moore, Jacob Bailey (1851). Lives of the Governors of New Plymouth and Massachusetts Bay. Boston: C. D. Strong. p. 335. OCLC 11362972.

- Morison, Samuel Eliot (1981) [1930]. Builders of the Bay Colony. Boston: Northeastern University Press. ISBN 0-930350-22-7.

- Palfrey, John Gorham (1860). History of New England During the Stuart Dynasty. Boston: Little, Brown. OCLC 1658888.

- Partridge, George (1919). History of the Town of Bellingham, Massachusetts. Bellingham, MA: Town of Bellingham. OCLC 12220440.

- Ryskamp, Charles (November 1959). "The New England Sources of The Scarlet Letter". American Literature. Duke University Press. 31 (3): 257–272. doi:10.2307/2922524. JSTOR 2922524.

- Watts, Jenny Chamberlain; Cutter, William Richard; Massachusetts Historical Society (1908). A Documentary History of Chelsea. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. OCLC 1172330.

- Whitmore, William Henry (1870). The Massachusetts Civil List for the Colonial and Provincial Periods, 1630–1774. Albany, NY: J. Munsell. OCLC 19603340.

- Proceedings of the Massachusetts Historical Society, 1884–1885. Boston: Massachusetts Historical Society. 1885. OCLC 1695300.

Further reading

- Anderson, Robert Charles. "Bellingham, Richard (1591/2–1672)". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (online ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/2058. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Henderson, Thomas Finlayson (1885). . In Stephen, Leslie (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. 4. London: Smith, Elder & Co.