| Rififi | |

|---|---|

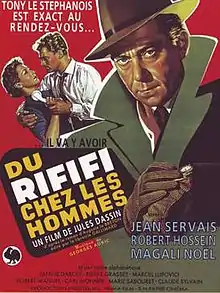

Film poster with original French title | |

| Directed by | Jules Dassin |

| Written by |

|

| Produced by |

|

| Starring |

|

| Cinematography | Philippe Agostini |

| Edited by | Roger Dwyre |

| Music by | Georges Auric |

| Distributed by | Pathé (France) |

Release date |

|

Running time | 115 minutes |

| Country | France |

| Language | French |

| Budget | $200,000[1][2] |

Rififi (French: Du rififi chez les hommes[lower-alpha 1]) is a 1955 French crime film adaptation of Auguste Le Breton's novel of the same name. Directed by American blacklisted filmmaker Jules Dassin, the film stars Jean Servais as the aging gangster Tony "le Stéphanois", Carl Möhner as Jo "le Suédois", Robert Manuel as Mario Farrati, and Jules Dassin as César "le Milanais". The foursome band together to commit an almost impossible theft, the burglary of an exclusive jewelry shop in the Rue de la Paix. The centerpiece of the film is an intricate half-hour heist scene depicting the crime in detail, shot in near silence, without dialogue or music. The fictional burglary has been mimicked by criminals in actual crimes around the world.[5][6]

After he was blacklisted from Hollywood, Dassin found work in France where he was asked to direct Rififi. Despite his distaste for parts of the original novel, Dassin agreed to direct the film. He shot Rififi while working with a low budget, without a star cast, and with the production staff working for low wages.[2]

Upon the initial release of the film, it received positive reactions from audiences and critics in France, the United States, and the United Kingdom. The film earned Dassin the award for Best Director at the 1955 Cannes Film Festival.[7] Rififi was nominated by the National Board of Review for Best Foreign Film. Rififi was re-released theatrically in both 2000 and 2015[8] and is still highly acclaimed by modern film critics as one of the greatest works in French film noir.[9]

Plot

Tony "le Stéphanois", a criminal who has served a five-year prison term for a jewel heist, is out on the street and down on his luck. His friend Jo approaches him about a smash-and-grab proposed by mutual friend Mario in which the trio would cut the glass on a Parisian jeweler's front window in broad daylight and snatch some gems. Tony declines. He then learns that his old girlfriend, Mado, took up in his absence with gangster Parisian nightclub owner Pierre Grutter. Finding Mado working at Grutter's, Tony invites her back to his rundown flat. She is obviously well-kept, and Tony savagely beats her for being so deeply involved with Grutter. Tony changes his mind about the heist; he now accepts on the condition that rather than merely robbing the window, they will take on the more difficult but more lucrative task of robbing the store's safe. Mario suggests they employ the services of Italian compatriot César, a safecracker. The four devise and rehearse an ingenious plan to break into the store and disable its sophisticated alarm system.

The caper begins with the group chiseling through a cement ceiling from an upstairs flat on a Sunday night. The suspenseful break-in is completed, and the criminals appear to escape without leaving any trace of their identities. However, without the others' knowledge, César pocketed a diamond ring as a bauble for his lover Viviane, a chanteuse at Grutter's club. The heist makes headline news and the four men arrange to fence the loot with a London contact. Meanwhile, Grutter has seen Mado and her injuries, and she breaks off their relationship. Infuriated at Tony's interference in his life, Grutter gives heroin to his drug-addicted brother Rémy and tells him to murder Tony. But then, the other Grutter brother, Louis, shows them the diamond César gave to Viviane and they realize that César, Mario, and Tony were responsible for the jewel theft. Grutter forces César to confess. Forsaking a FF10 million police reward, Grutter decides to steal the jewels from Tony's gang, with Rémy brutally murdering Mario and his wife Ida when they refuse to reveal where the loot is hidden. Tony retrieves it from the couple's apartment and anonymously pays for a splendid funeral for them. He then goes looking for Grutter and stumbles onto the captive César, who confesses having squealed. Citing "the rules," Tony ruefully kills him.

Meanwhile, seeking to force their adversaries' hand, Grutter's thugs kidnap Jo's five-year-old son Tonio and hold him for ransom. The London fence arrives with the payoff, after which Tony leaves to single-handedly rescue the child by force, advising Jo it is the only way they will see him alive. With Mado's help, he tracks Tonio down at Grutter's country house and kills Rémy and Louis while rescuing him. On the way back to Paris, Tony learns Jo has cracked under the pressure and agreed to meet Grutter at his house with the money. When Jo arrives Grutter tells him Tony has already snatched the child and kills him. Seconds too late to save his friend, Tony is mortally wounded by Grutter but kills him as Grutter tries to flee with the loot. Bleeding profusely, Tony drives maniacally back to Paris and delivers Tonio home safely before dying at the wheel as police and bystanders close in on him and a suitcase filled with FF120 million in cash. Jo's wife, Louise, takes her child from the car and leaves the suitcase and the body to police.

Cast

- Jean Servais as Tony "le Stéphanois": A gangster who recently returned from serving five years in prison for jewel theft. The eldest member in on the heist, Tony is godfather of namesake Tonio, son of Jo "le Suédois".

- Carl Möhner as Jo "le Suédois": A young Swedish gangster Tony took the five-year rap for. Jo invites Tony in on the heist. "Le Suédois" actually means "the Swede" in French.

- Robert Manuel as Mario Ferrati: A happy-go-lucky Italian gangster who came up with the original idea for a jewel heist.

- Jules Dassin as César "le Milanais": An expert safecracker hired by Tony with a weakness for women. Dassin played the role under the pseudonym of Perlo Vita.[2]

- Magali Noël as Viviane: a night-club singer who gets involved with César "le Milanais"; she sings the film's title song.

- Claude Sylvain as Ida: Mario Ferrati's wife

- Marcel Lupovici as Pierre Grutter: Leader of the Grutter gang and owner of the night-club L'Âge d'Or.

- Robert Hossein as Rémy Grutter: A member of the Grutter gang, addicted to heroin.

- Pierre Grasset as Louis Grutter: A member of the Grutter gang.

- Marie Sabouret as Mado: The former lover of Tony "le Stéphanois".

- Dominique Maurin as Tonio, the young son of Jo "le Suédois".

- Janine Darcey as Louise, Jo's wife and the mother of Tonio.

Production

Development

The film Rififi was originally to be directed by Jean-Pierre Melville, a later luminary of the heist film genre. Melville gave his blessing to American director Jules Dassin when the latter asked for his permission to take the helm.[1] It was Dassin's first film in five years.[10] He had been blacklisted in Hollywood after fellow director Edward Dmytryk named him a Communist to the House Committee on Un-American Activities in April 1951.[1][10] Subsequently, Dassin attempted to rebuild his career in Europe. Several such film projects were stopped through long-distance efforts by the US government.[11] Dassin attempted a film L'Ennemi public numero un, which was halted after stars Fernandel and Zsa Zsa Gabor withdrew under American pressure.[10] An attempt to film an adaptation of Giovanni Verga's Mastro don Gesualdo in Rome was halted by the US Embassy.[1] Dassin received an offer from an agent in Paris, France where he met producer Henri Bérard who had acquired the rights to Auguste Le Breton's popular crime novel Du Rififi chez les hommes.[1] Bérard chose Dassin due to the major success in France of Dassin's previous film The Naked City.[1]

Using his native English, Dassin wrote the screenplay to Rififi in six days with the help of screenwriter René Wheeler, who subsequently took the material and translated it to French.[1] Dassin hated the novel; he was repelled by the story's racist theme in which the rival gangsters were dark Arabs and North Africans pitted against light-skinned Europeans. As well, the book portrayed disquieting events such as necrophilia—scenes that Dassin did not know how to bring to the big screen.[1][12][13] Bérard suggested making the rival gang Americans, assuming Dassin would approve. Dassin was against this idea as he didn't want to be accused of taking oblique revenge on screen. Dassin downplayed the rival gangsters' ethnicity in his screenplay, simply electing the Germanic "Grutter" as surname.[1] The greatest change from the book was the heist scene, which spanned but ten pages of the 250-page novel. Dassin focused his screenplay on it to get past other events he did not know what to do with.[12] As produced, the scene takes a quarter of the film's running time and is shot with only natural sound, with no spoken words or music.[1]

Filming

Working with a budget of $200,000, Dassin could not afford top stars for the film.[2][13] To carry the lead role, Dassin selected Jean Servais, an actor whose career had slumped due to alcoholism.[1] For Italian gangster Mario Ferrati, Dassin cast Robert Manuel after seeing him perform a comic role as a member of Comédie-Française.[1] After a suggestion made by the wife of the film's producer, Dassin cast Carl Möhner as Jo the Swede.[1] Dassin would use Möhner again in his next film He Who Must Die.[1] Dassin himself played the role of the Italian safecracker César the Milanese.[1] Dassin explained in an interview that he "had cast a very good actor in Italy, whose name escapes me, but he never got the contract!...So I had to put on the mustache and do the part myself".[1]

Rififi was filmed during the wintertime in Paris and used real locations rather than studio sets.[2][14] Due to the low budget, the locations were scouted by Dassin himself.[2] Dassin's fee for writing, directing, and acting was US$8,000.[13] Dassin's production designer, to whom he referred as "one of the greatest men in the history of cinema", was Alexandre Trauner. Out of friendship for Dassin, Trauner did the film for very little money.[1] Dassin argued with his producer Henri Bérard on two points: Dassin refused to shoot the film when there was sunlight claiming that he "just wanted grey";[12] and there were to be no fist fights in the film. Such fight scenes had been important to the popular success in France of the Lemmy Caution film series.[12]

Rififi's heist scene was based on an actual burglary that took place in 1899 along Marseille's cours St-Louis. A gang broke into the first floor offices of a travel agency, cutting a hole in the floor and using an umbrella to catch the debris in order to make off with the contents of the jeweler's shop below.[15] The scene where Tony regretfully chooses to kill César for his betrayal of the thieves' code of silence was filmed as an allusion to how Dassin and others felt after finding their contemporaries willing to name names in front of the House Un-American Activities Committee.[14] This act was not in the original novel.[12]

Music and title

Georges Auric was hired as the composer for the film. Dassin and Auric originally could not agree about scoring the half-hour caper scene. After Dassin told Auric he did not want music, Auric claimed he would "protect [him]. I'm going to write the music for the scene anyways, because you need to be protected". After filming was finished, Dassin showed the film to Auric once with music and once without. Afterward, Auric agreed the scene should be unscored.[1]

In 2001, Dassin admitted that he somewhat regretted the Rififi theme song, utilized only to explain the film's title which is never mentioned by any other film characters.[1] The title (World War I French military slang) is almost un-translatable into English; the closest attempts have been "rough and tumble" and "pitched battle."[3] Dassin mistakenly thought the author had created the word himself to refer to Moroccan Berbers because of the Rif War.[13] The song was written in two days by lyricist Jacques Larue and composer Philippe-Gérard after Dassin turned down a proposal by Louiguy.[1] Magali Noël was cast as Viviane, who sings the film's theme song.[1] Noël would later act for Italian director Federico Fellini, appearing in three of his films.[1]

Release

Rififi debuted in France on 13 April 1955.[16] The film was banned in some countries due to its heist scene, referred to by the Los Angeles Times reviewer as a "master class in breaking and entering as well as filmmaking".[17] The Mexican interior ministry banned the film because of a series of burglaries mimicking its heist scene.[5] Rififi was banned in Finland in 1955 and released in severely cut form in 1959 with an additional tax because of its content.[18][19] In answer to critics who saw the film as an educational process that taught people how to commit burglary, Dassin claimed the film showed how difficult it was to actually carry out a crime.[11]

Rififi was a popular success in France which led to several other Rififi films based on le Breton's stories.[20] These films include Du rififi chez les femmes (1959), Du rififi à Tokyo (1963), and Du rififi à Paname (1966).[21] On its United Kingdom release, Rififi was paired with the British science fiction film The Quatermass Xperiment as a double bill; this went on to be the most successful double-bill release in UK cinemas in all of 1955.[22] The film was offered distribution in the United States on the condition that Dassin renounce his past, declaring that he was duped into subversive associations. Otherwise, his name would be removed from the film as the writer and director.[23][24] Dassin refused and the film was released by United Artists who set up a dummy corporation as the distributing company.[24][25] The film was distributed successfully in America with Dassin listed in the credits; in this way he was the first to break the Hollywood blacklist.[1][25] Rififi was released in the United States first with subtitles and then later with an English dub under the title Rififi...Means Trouble!.[1] The film was challenged on release by The Roman Catholic Legion of Decency; as a result, the film suffered three brief cuts, and opened with a title card quoting the Book of Proverbs stating "When the wicked are multiplied, crime shall be multiplied: but the just shall see their downfall". After this change, the film passed with a B rating.[1] In 2005, Variety announced that Stone Village Pictures had acquired the remake rights to Rififi, the producers intending to place the film in a modern setting with Al Pacino taking the lead role.[26]

Home media

In North America, Rififi has been released on both VHS and DVD. The VHS print has been reviewed negatively by critics. Roger Ebert referred to it as "shabby" while Bill Hunt and Todd Doogan, the authors of The Digital Bits Insider's Guide to DVD, referred to the VHS version as "horrible" and with "crappy subtitles".[2][27] The Criterion Collection released a DVD version of the film on 24 April 2001.[28][29] In the United Kingdom, Rififi was released on DVD by Arrow Films on 21 April 2003, and on Region B Blu-ray by the same publisher on 9 May 2011.[30][31][32] The film was released to Blu-Ray and re-released to DVD in Region 1 by Criterion on 14 January 2014.

Critical reception

Upon its original release, film critic and future director François Truffaut praised the film, stating that "Out of the worst crime novel I ever read, Jules Dassin has made the best crime film I've ever seen" and "Everything in Le Rififi is intelligent: screenplay, dialogue, sets, music, choice of actors. Jean Servais, Robert Manuel, and Jules Dassin are perfect."[9] French critic André Bazin said that Rififi brought the genre a "sincerity and humanity that break with the conventions of a crime film, and manage to touch our hearts".[6] In the February 1956 issue of the French film magazine Cahiers du cinéma, the film was listed as number thirteen in the top twenty films of 1955.[33] The film was well received by British critics who noted the film's violence on its initial release. The Daily Mirror referred to the film as "brilliant and brutal" while the Daily Herald made note that Rififi would "make American attempts at screen brutality look like a tea party in cathedral city".[6] The American release of the film also received acclaim. Bosley Crowther of The New York Times referred to the film as "perhaps the keenest crime film that ever came from France, including "Pépé le Moko" and some of the best of Louis Jouvet and Jean Gabin."[34] The National Board of Review nominated the film as the Best Foreign Film in 1956.[35]

Rififi was re-released for a limited run within America on 21 July 2000 in a new 35 mm print containing new, more explicit subtitles that were enhanced in collaboration with Dassin.[28][36] The film was received very well by American critics on its re-release. The film ranking website Rotten Tomatoes reported that 93% of critics had given the film positive reviews, based upon a sample of 41.[37] At Metacritic, which assigns a normalized rating out of 100 to reviews from mainstream critics, the film has received an average score of 97, based on 13 reviews.[28] Kenneth Turan of the Los Angeles Times wrote the film was the "benchmark all succeeding heist films have been measured against... It's a film whose influence is hard to overstate, one that proves for not the last time that it's easier to break into a safe than fathom the mysteries of the human heart."[3] Lucia Bozzola of the online database Allmovie gave the film the highest possible rating of five stars, calling it "The pinnacle of heist movies" and "not only one of the best French noirs, but one of the top movies in the genre."[36] In 2002, critic Roger Ebert added the film to his list of "Great Movies" stating "echoes of [Rififi] can be found from Kubrick's The Killing to Tarantino's Reservoir Dogs. They both owe something to John Huston's The Asphalt Jungle (1950), which has the general idea but not the attention to detail."[2] Rififi placed at number 90 on Empire's list of The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema.[38]

Among negative reviews of the film, Dave Kehr of the Chicago Reader felt that "the film turns moralistic and sour in the last half, when the thieves fall out."[39] The critic and director Jean-Luc Godard regarded the film negatively in comparison to other French crime films of the era, noting in 1986 that "today it can't hold a candle to Touchez pas au grisbi which paved the way for it, let alone Bob le flambeur which it paved the way for."[40]

See also

- 1955 in film

- List of French films of 1955

- List of French-language films

- List of crime films of the 1950s

- Rifampicin, Italian-developed antibiotics (rifamycins) named after the film

- Big Deal on Madonna Street

- Heist film

Notes

- ↑ The title Du Rififi chez les hommes [dy ʁi.fi.fi ʃe lez‿ɔm] does not directly translate into English. A rough translation would be "Some rumble amongst men". Rififi is a slang word deriving from rif, the French military term for "combat zone" during the First World War, ultimately from the Middle French rufe, "fire" and Latin rūfus, "red".[3][4]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Rififi (Supplemental slideshow on DVD). New York, New York: The Criterion Collection. 2001 [1955]. ISBN 0-7800-2396-X.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Ebert, Roger (6 October 2000). "Rififi (1954)". Chicago Sun-Times.

- 1 2 3 Turan, Kenneth (6 October 2000). "Movie Review; 'Rififi' Remains the Perfect Heist (Movie); Jules Dassin's 1955 thriller has lost none of its power to captivate and entertain an audience". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Le Nouveau Petit Robert, dictionnaire alphabétique et analogique de la langue française ISBN 2-85036-668-4 and Le Petit Larousse illustré ISBN 2-03-530206-4.

- 1 2 The Lethbridge Herald, 18 August 1956 via www.newspaperarchive.com (subscription required)

- 1 2 3 Powrie 2006, p. 71.

- ↑ "Festival de Cannes: Rififi". festival-cannes.com. Retrieved 31 January 2009.

- ↑ Rialto Pictures (6 August 2015). "RIFIFI - Trailer". Vimeo. Vimeo, LLC. Retrieved 16 August 2015.

- 1 2 Truffaut 1994, p. 209.

- 1 2 3 Powrie 2006, p. 76.

- 1 2 Berg, Sandra (November 2006). "When Noir Turned Black". Written by. Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 24 December 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rififi (Jules Dassin Interview). New York, New York: The Criterion Collection. 2001 [1955]. ISBN 0-7800-2396-X.

- 1 2 3 4 Sragow, Michael (16 July 2000). "FILM; A Noir Classic Makes It Back From the Blacklist". The New York Times.

- 1 2 3 Powrie 2006, p. 77.

- ↑ Powrie 2006, p. 73.

- ↑ Bozzola, Lucia. "Rififi". AllMovie. Archived from the original on 26 July 2012. Retrieved 22 August 2017.

- ↑ Luther, Claudia (1 April 2008). "Blacklisted Director Jules Dassin Dies at 96". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ Törnudd 1986, p. 152.

- ↑ Sedergren, Jari. (2006). Taistelu elokuvasensuurista : valtiollisen elokuvatarkastuksen historia 1946-2006. Helsinki: Suomalaisen Kirjallisuuden Seura. ISBN 9517468121. OCLC 85017263.

- ↑ Hardy 1997, p. 118.

- ↑ Hardy 1997, p. 119.

- ↑ Lenera, Dr (10 May 2015). "DOC'S JOURNEY INTO HAMMER FILMS #26: THE QUATERMASS XPERIMENT [1955]". Horror Cult Films. Archived from the original on 14 July 2017. Retrieved 13 August 2017.

Timed to coincide with the second TV Quatermass series Quatermass 2, the film went out on a double bill with either the short The Eric Winstone Band Show or Rififi, the latter becoming the most successful double bill release of 1955 in the UK.

- ↑ Levy 2003, p. 343.

- 1 2 Levy 2003, p. 344.

- 1 2 Foerstel 1998, p. 165.

- ↑ Fleming, Michael (18 August 2005). "Pacino in hest [sic] mode with 'Rififi'". Variety. Retrieved 8 January 2009.

- ↑ Hunt and Doogan 2004, p. 330.

- 1 2 3 "Rififi (re-release) (2001): Reviews." Metacritic. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ↑ Hunt and Doogan 2004, p. 329.

- ↑ Sven Astanov. "Rififi Blu-ray Review". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved 17 July 2011.

- ↑ "Arrow Films - RIFIFI". Arrow Films. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ↑ "Rififi [1954]". Amazon UK. 21 April 2003. Retrieved 15 November 2008.

- ↑ Hillier 1985, p. 285.

- ↑ Crowther, Bosley (6 June 1956). "Rififi (1955)". The New York Times. Retrieved 7 January 2009.

- ↑ "Rififi: Awards". Allmovie. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- 1 2 Bozzola, Lucia. "Rififi: Review". Allmovie. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ↑ "Rififi - Rotten Tomatoes". Rotten Tomatoes. Flixster. Archived from the original on 3 September 2012. Retrieved 11 September 2012.

- ↑ "The 100 Best Films Of World Cinema". Empire. Retrieved 22 July 2010.

- ↑ Kehr, David (26 October 1985). "Rififi Capsule". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 17 April 2010.

- ↑ Godard 1986, p. 127.

Bibliography

- Powrie, Phil (2006). The Cinema of France. Wallflower Press. ISBN 1-904764-46-0. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Hunt, Bill; Todd Doogan (2004). The Digital Bits Insider's Guide to DVD: Insider's Guide to DVD. McGraw-Hill Professional. ISBN 0-07-141852-0. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Hardy, Phil (1997). The BFI Companion to Crime. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-304-33215-1. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Truffaut, François; Leonard Mayhew (1994). The Films In My Life. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80599-5. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Levy, Emanuel (2003). All about Oscar: The History and Politics of the Academy Awards. Continuum International Publishing Group. ISBN 0-8264-1452-4. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Hillier, Jim; Nick Browne; David Wilson (1985). Cahiers Du Cinema: Volume I: The 1950s. Neo-Realism, Hollywood, New Wave. Routledge. ISBN 0-415-15105-8. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Törnudd, Klaus (1986). Finland and the International Norms of Human Rights. Martinus Nijhoff Publishers. ISBN 90-247-3257-3. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Foerstel, Herbert N. (1998). Banned in the Media: A Reference Guide to Censorship in the Press, Motion Pictures, Broadcasting, and the Internet. Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 0-313-30245-6. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

- Godard, Jean Luc; Jean Narboni; Tom Milne (1986). Godard on Godard. Da Capo Press. ISBN 0-306-80259-7. Retrieved 13 August 2009.

External links

- Rififi at AllMovie

- Rififi at IMDb

- Rififi at Metacritic

- Rififi at Rotten Tomatoes

- Rififi at the TCM Movie Database

- Rififi: A Global Caper an essay by J. Hoberman at the Criterion Collection