Robert Coleman | |

|---|---|

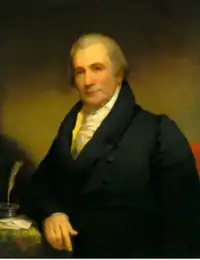

Coleman by Jacob Eichholtz circa 1812-1815 | |

| Born | November 4, 1748 |

| Died | August 14, 1825 (aged 76) |

| Occupation(s) | Ironmaster, Industrialist |

| Spouse | Anne Old |

Robert Coleman (November 4, 1748 - August 14, 1825) was an American industrialist and politician who became Pennsylvania's first millionaire.[1][2]

Early life

Coleman was born in Castlefin in County Donegal, Ireland, one of eight children of Thomas Coleman.[2] Although born in Ireland, his family was English.[3] He immigrated to America, arriving in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania in 1764 when he was sixteen years old.[4] According to tradition, he brought with him two letters of introduction and three guineas.[5]

He worked as a clerk for merchant Mark Biddle who was impressed with Coleman's penmanship and attention to detail.[2] This led to Coleman being hired as a bookkeeper by prominent iron masters Curtis and Peter Grubb of the Hopewell Forge furnace.[2] While working for the Grubbs, Coleman learned about the iron making industry and what it took to become an ironmaster.[3][5] He also learned that operating an iron furnace it took little cash, as workers were paid with supplies which were, in turn, acquired by barter from iron shipments.[5]

After six months at the Hopewell Forge, he moved on to become a clerk at James Old's Quittapahilla Force furnace in Berks County, Pennsylvania.[2][3]

Ironmaster

Shortly after his marriage of Old's daughter, Coleman leased the Salford Forge near Norristown, Pennsylvania in 1773.[2] He leased the Elizabeth Furnace near Manheim in Lancaster County in 1776 from its owners creditors.[3] Coleman turned the struggling ironworks into a profitable business by capitalizing on the Continental Army's need for ammunition in the Revolutionary War.[2] He reduced costs by using Hessian prisoners as laborers to make cannonballs and grapeshot at the Elizabeth and Salford Furnaces.[2][5] His resulting profits made him the first millionaire in Pennsylvania.[5]

Coleman used his profits to purchase all of the shares in the Elizabeth Furnace between 1780 and 1794.[3] He also purchased the Speedwell Forge from his father-in-law in 1785.[3] He also acquired shares of the Upper and Lower Hopewell Forges (not the similarly named Hopewell Furnace).[1][5] He acquired a 1/6 interest in the Cornwall Furnace from the Grubbs in 1786, and an added 2/3 share in 1798, for a total of 5/6 ownership.[3] This bought out Curtis Grubb and half Henry Bates Grubb's shares.[3] Most importantly, the Cornwall Furnace purchase included an equal share in the Cornwall Ore Bank.[3] This was one of the richest iron deposits in the United States.[3]

Coleman constructed Colebrook Furnace in 1791.[3] He also acquired a share of the Martic Forge in 1801,[3] His resulting profits made him the first millionaire in Pennsylvania.[2] His sons, James, Robert Bird, and William trained at Speedwell Forge when they came of age, moving on to manage other operations.[5] In 1809, he delegated most of the operations to his sons.[5]

Politics and military

For more than three decades, Coleman served as a politician in Pennsylvania and leader of the Federalist Party in Lancaster County.[2][6] In 1776, he attended the Pennsylvania State Constitutional Convention.[2] During the Revolutionary War, Coleman served briefly in the Pennsylvania militia lieutenant, marching aid in the doomed defense of New York.[5] However, he returned home to what was probably a more important service to the war effort—making iron.[5]

He served in the Pennsylvania Legislature in 1783.[4] In 1787, he was a delegate to the Pennsylvania Convention to ratify the United States Constitution.[2] He helped edit the state's charter in 1790.[5] He was a Presidential elector in 1792.[2] In 1795, Coleman was Captain of the Lancaster Troop of Light Horse.[2] In this capacity, he led thirty-five cavalrymen to aid in the suppression of the Whiskey Rebellion.[2]

He was an elector again in 1796; this time he cast one of the three critical votes in the selecting John Adams, rather than Thomas Jefferson, as president.[3] He also served as an Associate Judge from 1791 to 1811.[2] He also made an unsuccessful run for the United States Senate.[5]

Honors

- First stablished in 1827 and reestablished in 1948, the Robert Coleman Chair of History at Dickinson College is one of the oldest endowed professorships in the United States.[2]

- His portrait by Jacob Eichholtz hangs in the National Gallery of Art in the Smithsonian Institution in Washington, D.C.[4] An identical painting is in the collection of the New York Historical Society Museum & Library in New York City.[4] It is not known which painting is the original.[4]

- Coleman is remembered with an historic marker in the cemetery of St. James Episcopal Church in Lancaster, Pennsylvania.[7]

Personal

_by_Jacob_Eichholtz_(ca._1820).jpg.webp)

On October 4, 1773, Coleman married Anne Old (1756 – 1884), the oldest daughter his employer James Old (1730 – 1809), at Reading Furnace, Chester County, Pennsylvania.[2][8][3] The couple had nine children: William, Edward, Thomas Burd, Richard, James, Margaret, Ann Caroline, Harriet, and Sarah.[9][5] In 1791, he built Elizabeth Farms house overlooking his Colebrook Furnace on 400 fertile acres.[5]

Starting in 1802, Coleman served as a trustee of Dickinson College in Carlisle, Pennsylvania for 23 years.[2] He also served on the board of Franklin College and was a director of the Bank of Pennsylvania.[5]

The Colemans moved to a large brick mansion on East King Street in Lancaster, Pennsylvania in 1809, along with their youngest children: thirteen-year-old Ann Caroline, nine-year-old Harriet, and seven-year-old Sarah.[9] Harriet died the year after the move, followed by Robert a year later.[5]

In 1818, attorney James Buchanan started courting Anne Caroline who was a "catch" with her social standing and wealth.[9][5] Buchanan did not have a status or background, but was beginning to gain a reputation in law and politics, having served as both prosecuting attorney and state assemblyman.[9] The two became engaged in the summer of 1819.[9] Coleman was apparently unhappy with Buchanan's checkered history at Dickinson College where he was disciplined by faculty twice and dismissed on one occasion.[9]

During October and November 1819, Buchanan was busy with the Columbia Bridge Company Supreme Court case in Philadelphia, many clients impacted by a collapsing economy, and with the Missouri problem with regards to slavery at the legislature—and apparently neglected Anne Caroline.[9] Town gossips concluded that Buchanan "was tremendously ambitious to make money; that he was more affable and friendly to many young ladies than he ought to be as one betrothed; and finally, that he had been something less than an ardent suitor of Ann Coleman in recent weeks."[9] They came to the untrue conclusion that Buchanan was marrying Anne Caroline for her money.[9] In November, Anne Caroline heard the gossip and, as one of her friends wrote, began to believe “that Mr. Buchanan did not treat her with that affection that she expected from the man she would marry, and in consequence of his coolness she wrote him a note telling him that she thought it was not regard for her that was his object, but her riches.”[9] Buchanan replied, but did not give an explanation for his recent behavior.[9] Then, when he returned to Lancaster from Philadelphia, he first visited a colleague's home and spent the afternoon with the man's wife and her unmarried sister.[5][9] In anger, Ann Carolina sent a letter, breaking the engagement.[9] She wrote, “I do not wish, nor, since you are a gentleman, do I expect, to meet you again."[5]

As Buchanan dealt with the worst of the financial crisis on November 29, 1819, Ann Caroline traveled to Philadelphia on December 4 to visit her sister Margaret who had married United States Congressman Joseph Hemphill in September 1806.[10][9] Just after midnight on December 9, 1819 ,Ann Caroline was dead.[9] Judge Thomas Kittera wrote, “At noon yesterday, I met this young lady on the street, in the vigour [sic] of health, and but a few hours after, her friends were mourning her death. She had been engaged to be married, and some unpleasant misunderstanding occurring, the match was broken off. This circumstance was preying on her mind. In the afternoon she was laboring under a fit of hysterics; in the evening she was so little indisposed that her sister visited the theatre. After night she was attacked with strong hysterical convulsions, which induced the family to send for physicians, who thought this would soon go off, as it did; but her pulse gradually weakened until midnight, when she died. Dr. Chapman, who spoke with Dr. Physick, says it is the first instance he ever knew of hysteria producing death.” At the time, some believe this to be a suicide, but there was no proof.[9] However, Coleman would not let Buchanan walk as a mourner at her funeral.[5] Buchanan was so devastated by her death that he vowed never to marry as "his affections were buried in the grave.”[9] He eventually became the only bachelor President in the history of the United States.

Another daughter, Sarah, also is believed to have committed suicide.[5] Around 1824, William Augustus Muhlenberg, co-rector of St. James Episcopal Church in Lancaster, courted Sarah.[11] Coleman served on the vestry of St. James and had a bitter dispute with Muhlenberg over the latter offering evening worship services.[11] Coleman then banned Muhlenberg from his house.[11] Muhlenberg wrote in his diary, “But for no earthly consideration whatever, not even the attainment of the dear object of my heart will I sacrifice what I believe to be the interests of my church. O lord, help me!'”[11] The dispute continued for a year, before coming before the church council again, but by that time Coleman was too ill to protest.[5] After her father's death in August 1825, Sarah hoped to marry Muhlenberg.[5] However, in his will, Coleman gave his sons Edward and James the right to approve of Sarah's spouse, and tied such approval to her inheritance.[5] Unfortunately, her brother Edward also dislike Muhlenberg, and even offered the church $5,000 only if the young rector was to leave.[5][11] Perhaps broken hearted, Sarah traveled to Philadelphia in the fall of 1825 where she died at the age of 23.[11]

Coleman died in Lancaster at age 77.[2] He was one of the wealthiest and most respected men in Pennsylvania at the time of his death.[2] He left Dickinson College dividends and fifty shares in the Carlisel Bank worth $1,140.[2]

His legacy was retained through the surviving companies of the Cornwall Iron Furnace company until the industry was replaced by steel manufacturing late in the 19th-century.

References

- 1 2 "A Blast From The Past: Cornwall Iron Furnace". Retrieved 2009-12-15.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 "Robert Coleman(1748-1825)". Dickinson College Archives and Special Collections. 2005. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Collection: Robert Coleman papers | Hagley Museum and Library Archives". findingaids.hagley.org. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Robert Coleman (1748-1825)". New York Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 Habecker, Jan (1987). "A Dynasty Tumbles". Pennsylvania Heritage (Winter).

- ↑ "Coleman, Robert, 1748-1825 - Social Networks and Archival Context". snaccooperative.org. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ↑ Pfingsten, Bill (February 6, 2008). "Robert Coleman Historical Marker". Historical Marker Database. Retrieved 2022-04-23.

- ↑ "Mrs. Robert Coleman (1756-1844)". New York Historical Society. Retrieved April 23, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 Klein, Philip Shriver (December 1955). "The Lost Love Of A Bachelor President". American Heritage. 7 (1).

- ↑ Futhey, J. Smith; Cope, Gilbert (881). History of Chester County, Pennsylvania with Genealogical and Biographical Sketches - Volume 2. Philadelphia: Louis H. Everts & Co. pp. 595–596. ISBN 9780788443879. Retrieved 22 March 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Brubaker, Jack. "The tragic story of another Coleman suitor". LancasterOnline. Retrieved 2022-04-23.