A roller derby scrimmage in Utah (2012) | |

| Highest governing body | WFTDA, MRDA, JRDA, FIRS |

|---|---|

| Nicknames | Derby |

| First played | 1935, Chicago, Illinois |

| Clubs | 4,700+ |

| Characteristics | |

| Contact | Full |

| Team members | 15 on roster, up to 5 on track during each jam.[1] |

| Type | Indoor, roller sport |

| Equipment | Roller skates, helmet, knee pads, elbow pads, wrist guards, mouthguard |

| Venue | Roller rink, pitch |

| Presence | |

| Olympic | No |

Roller derby is a roller skating contact sport played on an oval track by two teams of five skaters. It is played by approximately 1,250 amateur leagues worldwide, mostly in the United States.[2]

A 60-minute roller derby game, or bout, is a series of two-minute timed jams. Each team, typically with a roster of 15, fields five skaters during each jam: one jammer, designated with a star on their helmet, and four blockers. The jammer scores a point for each opposing blocker they lap. The blockers simultaneously defend by hindering the opposing jammer, while also playing offense by maneuvering to aid their own jammer. Because roller derby uses a penalty box, power jams, in which one team has a temporary numerical advantage after a foul, can have a major effect on scoring.[3][4]

Overview

While the sport has its origins in the banked-track roller-skating marathons of the 1930s, Leo Seltzer and Damon Runyon are credited with evolving the sport to its competitive form. Professional roller derby quickly became popular; in 1940, more than 5 million spectators watched in about 50 American cities. In the ensuing decades, however, it predominantly became a form of sports entertainment, where theatrical elements overshadowed athleticism. Gratuitous showmanship largely ended with the sport's grassroots revival in the first decade of the 21st century.[5] Although roller derby retains some sports entertainment qualities such as player pseudonyms and colorful uniforms, it has abandoned scripted bouts with predetermined winners.[6]

Modern roller derby is an international sport, mostly played by amateurs. It was under consideration as a roller sport for the 2020 Summer Olympics.[7][8][9] Fédération Internationale de Roller Sports (FIRS), recognized by the International Olympic Committee as the official international governing body of roller sports, released its first set of Roller Derby Rules for the World Roller Games, organised by World Skate, that took place September 2017 in Nanjing, China. Most modern leagues (and their back-office volunteers) share a strong "do-it-yourself" ethic[10] that combines athleticism with the styles of punk and camp.[11] As of 2020, the Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA) had 451 full member leagues and 46 apprentice leagues[12] and the Roller Derby Coalition of Leagues (RDCL) supporting women's banked track roller derby had eight full member leagues.[13]

Rules

Contemporary roller derby has a basic set of rules, with variations reflecting the interests of a governing body's member leagues. The summary below is based on the rules of the Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA).[1] In March 2010, Derby News Network said that more than 98% of roller derby competitions were conducted under WFTDA rules.[14] For example, members of the United Kingdom Roller Derby Association are required to play by WFTDA rules,[15] while members of the former Canadian Women's Roller Derby Association were encouraged to join the WFTDA.[16]

Basics of play

| Position | Helmet cover[1]: 7 | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Jammer | Star | Scores points by lapping opposing blockers.[1]: 7 |

| Blocker | None | Forms the pack,[17]: 18 hinders the opposing jammer from passing through the pack, and helps their team's jammer pass through the pack.[18] |

| Pivot | Stripe | A blocker who may be converted to a jammer during the course of a jam,[1]: 7 if the jammer's helmet cover is correctly transferred in a "star pass" maneuver.[17]: 29 The pivot is often an experienced player who establishes team strategy during play and sets the pace of the pack.[19][17]: 19 |

Roller derby is played in two periods of 30 minutes.[1]: 4 Two teams of up to 15 players each field up to five members for episodes called "jams". Jams last two minutes unless called off prematurely.[1]: 5 Each team designates a scoring player (the "jammer"); the other four members are "blockers". One blocker can be designated as a "pivot"—a blocker who is allowed to become a jammer in the course of play.[1]: 7 The next jam may involve different players of the 15 roster players, and different selections for jammer and pivot.[1]: 7

During each jam, players skate counterclockwise on a circuit track. Points are scored only by a team's jammer. After breaking through the pack and skating one lap to begin another "trip" through the pack, the jammer scores one point for passing any opposing blocker.[1]: 33 [note 1] The rules describe an "earned" pass; notably, the jammer must be in-bounds and upright. The jammer's first earned pass scores a point for passing that blocker and a point for each opponent blocker not on the track (for instance, serving a penalty, or when the opposition did not field five players for the jam). If the jammer passes the entire pack, it is a four-point scoring trip, commonly called a "grand slam".[note 1]

Each team's blockers use body contact, changing positions, and other tactics to help their jammer score while hindering the opposing team's jammer.

Jams

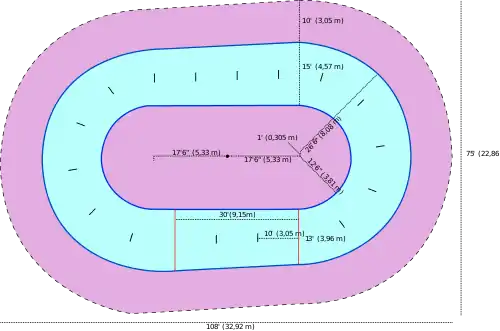

Play begins by blockers lining up on the track anywhere between the "jammer line" and the "pivot line" 30 feet in front. The jammers start behind the jammer line.[1]: 12 Jams begin on a single short whistle blast, upon which both jammers and blockers may begin engaging immediately.

The pack is the largest single group of blockers containing members of both teams skating in proximity, arranged such that each player is within 10 feet of the next.[1]: 11 Blockers must maintain the pack, but can skate freely within 20 feet behind and ahead of it, an area known as the "engagement zone".[1]: 13

The first jammer to break through the pack earns the status of "lead jammer".[1]: 7 A designated referee blows the whistle twice and continually points at the jammer to confer lead jammer status, which lets that jammer stop the jam at any time by repeatedly placing hands on hips.[1] Lead jammer status cannot be transferred to other skaters, but certain actions (such as being sent to the penalty box) cancel lead jammer status, meaning that the jam has no lead jammer and must continue for the full two-minute period.[1]: 8 If the jam is not called off by the lead jammer, it ends after two minutes.[1]: 5 If time remains in the period, teams then have 30 seconds to get on the track and line up for the next jam.[1]: 5 If the 30-minute period ends while a jam is underway, the jam plays out to its natural conclusion.

Blocking

A skater may block an opponent to impede their movement or to force them out of bounds. The blocker must be upright, skating counterclockwise, in bounds, and within the engagement zone. Groups of blockers on the same team typically create formations, known as walls, to prevent the opposing blocker from passing. Blocking with hands, elbows, head, and feet is prohibited, as is contact above the shoulders, below mid-thigh, or to the back.[1]: 14

Penalties

Referees penalize rules violations.[1]: 36 A player receiving a penalty is removed from play and must sit in the penalty box for 30 seconds of jam time.[1]: 29 If the jam ends during this interval, the player remains in the penalty box during the subsequent jam until the interval ends.[1]: 30 While the penalty is being served, the penalized player's team plays short-handed, as in ice hockey. A player "fouls out" of the game on the seventh penalty, and is required to return to the locker room.[1]: 32

A "power jam", derived from ice hockey's "power play", refers to a scenario when one team's jammer is sent to the penalty box.[20] In this case, that jammer's team cannot score. If the lead jammer is penalized, no one can prematurely end the jam.

It would be pointless to play if neither team could score; thus, both jammers cannot serve a penalty at the same time. If one jammer is sent to the penalty box while the opposing jammer is already serving a penalty, the opposing jammer is released from the penalty box early. The second jammer's penalty is then only as long as the amount of time the first jammer spent in the box.[1]: 31

Equipment

Players skate on four-wheeled ("quad") roller skates,[1]: 11 and are required to wear protective equipment, including a helmet, wrist guards, elbow pads, knee pads, and mouth guards. All current sets of roller derby rules explicitly forbid inline skates for players. (USARS requires quad skates for all skaters. WFTDA and MRDA permit inline skates for referees, but virtually all referees wear quad skates.) Individual teams may mandate additional gear, such as padded knee length pants, similar to what aggressive skateboarders wear, and gender specific gear such as a hard-case sports bra and protective cups.[1]: 39

Strategy and tactics

Offense and defense are played simultaneously,[21] a volatile aspect that complicates strategy and tactics. For example, one team's blockers may take offensive action to create a gap in the opposing wall for their jammer to pass through, but this same maneuver could potentially weaken their own defenses and allow the opposing team's jammer to score.[22][23]

Strategies (high-level plans toward achieving the game's goal, which is to outscore the opposition) include the following:

- Ending the jam: The lead jammer can "call off" or end the jam at any time, controlling the opposition's ability to score points. The strategy for a jam is not to score a lot of points but to outscore the opposition. Often, the lead jammer scores as many points as possible on the first scoring trip, and then ends the jam before the opposing jammer has the opportunity to score any points.[24] If the jammer gets the lead but is then passed by the opposing jammer, they may decide to call off the jam without scoring any points themselves in order to prevent the other team's jammer from scoring any points.

- Passing the star: The jammer for a team may "pass the star" (may perform a "star pass") to the pivot—that is, hand the helmet cover with the star to the pivot, which turns the pivot into the jammer.[1]: 9 Passing the star does not nullify any earned pass of an opponent that the former jammer made, but passing the star forward never constitutes an earned pass. A jammer might pass the star because of fatigue, injury, or because the pivot is in a better position to score.[25] Passing the star is also sometimes referred to as "passing the panty", as helmet covers are sometimes known as "panties".[26]

- Killing a penalty: Captained by the pivot, blockers adapt their play to a penalty situation. For example, a short-handed team may try to make the pack skate faster to slow down scoring action until the team returns to full strength.[19][note 2]

Tactics (deliberate conceptual tasks in support of the strategy) may include the following:

- Walling up: Two or more blockers skate together to make it difficult for the opposing team (especially its jammer) to maneuver. They may skate side by side and use a "wide stance" to maximize the blockade, but must not link with or grasp each other, or otherwise form an impenetrable connection.[1] The ability to suddenly form a wall denies the opposition time to respond. A wall can inhibit, slow down, and ultimately trap the opposing jammer. An effective wall may last for an entire jam. Variations on the tactic include the following:

- Backwards bracing, in which one skater, forward of the wall, skates backward to sight the jammer and direct teammates forming the wall.

- A skater may break off from the wall to actively challenge the opposing jammer, with a teammate replacing the skater in the wall.[27]

- If the opposing jammer tries to pass the wall on one side, players may abandon the other side to fortify the active side of the wall.

.jpg.webp)

- Jammer tactics, in response to a wall or other obstacles by the opposing team's defense, include the following:

- Pushing through gaps in the wall or inducing the wall to separate by use of physical force.

- Evading the obstacle to one side or the other.

- Juking, where the jammer seems to be skating to one side but quickly shifts to the other side.

- Rolling around the end of the obstacle (spinning 360°) to end up ahead of it.[28]

- Using teammates to impede the defense from adjusting, such as by setting screens.

- Using a whip, where one or more teammates grasp the jammer's hand(s) and swing the jammer forward, transferring speed and momentum to the jammer.[29]

- Apex Jump: Using the inside curve of the track to leap out of bounds but land in bounds, passing opposing players.

- Goating: The pack is defined as the largest group of in-bounds blockers, skating in proximity, containing members from both teams.[1]: 11 In the "goat-herding" tactic, one team surrounds a blocker of the opposing team and then slows so that that group becomes the pack. The rest of the opposing team, skating ahead, are thus put out of play and cannot legally block the goat-herders' jammer.

- Running back or recycling: When a skater bumps the opponent jammer off the track, the jammer can only re-enter the track behind the skater. The skater skates clockwise on the track toward the rear of the engagement zone to maximize the time the jammer must spend before returning to action.[30]

- Bridging: By separating up to 10 feet, blockers can stretch both the pack and the engagement zone, allowing teammates to keep hindering the opposition jammer. For example, in the strategy of running back (see above), coordinated action by the four skaters other than the jammer could force the opponent jammer to detour a full 40 feet before returning to action.[31]

Officials

WFTDA bouts are officiated by three to seven skating referees and many non-skating officials (NSOs).[1]: 35 Volunteer leagues adapt when fewer than the optimal number of officials are present.

Referees

Up to four referees skate on the inside of the track. In flat-track derby, up to three additional referees skate on the outside of the track. They call penalties, award points, and ensure safe game play.[1]: 36 Referees must wear skates and typically wear white and black stripes.[1]: 38

| Type | Number | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Head Referee | 1 | The head referee is responsible for the general supervision of the bout and has final authority on all rulings. The head referee skates as an inside pack referee, but is also responsible for issuing expulsions[1]: 35 and for announcing the results of official reviews.[1]: 38 |

| Pack Referees | Up to 5 | Pack referees are responsible for watching the skaters in the pack, assessing pack definition, and calling penalties. They are located both inside and outside the track.[1]: 35 [17]: 29 |

| Jammer Referees | 2 | Skating on the inside of the track,[17]: 29 a jammer referee watches the jammer of a designated team, awards points scored by their jammer,[1]: 36 signals whether their jammer has achieved lead jammer status,[17]: 29 and signals the end of the jam if their jammer is lead and calls off the jam. Jammer referees wear a wristband (and optionally a helmet cover) in that team's color to identify which team's jammer they are watching.[1]: 35 |

Non-skating officials (NSOs)

NSOs take up a range of positions inside and outside the track, start and time the jams, record and display scores and penalties communicated by referees, record the number of each skater on track for a given jam, and time and record skaters in the penalty box.

| Type | Number | Responsibility |

|---|---|---|

| Scorekeepers | 2 | Record points scored by jammers, as indicated by the Jammer Referees.[1]: 36 |

| Penalty Trackers | 1 (min) | Record each skater's penalties[1]: 36 and notify the head referee of skaters in the current jam who are in danger of fouling out.[1] |

| Penalty Box Manager | 1 | The manager is the head of the affairs within the penalty box. The manager can call penalties for penalty box violations or illegal procedures (such as removing the helmet in the penalty box). Also, the manager points where the player is assigned to sit, times the jammers, and executes any necessary jammer swap. |

| Penalty Box Timers | 2 (min) | Ensure skaters sent to the penalty box serve their entire penalties,[1]: 36 and notify referees if any do not.[1] |

| Jam Timer | 1 | Start jams, signal when a jam runs to the full two minutes, time the 30 seconds between jams,[1]: 36 and call official timeouts. |

| Lineup Tracker | 2 | Record the role (Jammer, Pivot, or Blocker) of every player on the track in each jam.[1]: 5 |

| Scoreboard Operator | 1 | Update the scoreboard after every scoring pass.[1]: 36 |

History

Professional endurance races

The growing popularity of roller skating in the United States led to the formation of organized multi-day endurance races for cash prizes as early as the mid-1880s.[32][33][34] Speed and endurance races continued to be held on both flat and banked tracks in the century's first three decades[35] and spectators enjoyed the spills and falls of the skaters.[36][37] The term derby was used to refer to such races by 1922.[38][note 3]

Evolution to contact sport

The endurance races began to transform into the contemporary form of the sport in the mid-1930s, when promoter Leo Seltzer[note 4][note 5] created the Transcontinental Roller Derby, a month-long simulation of a road race between two-person teams of professional skaters.[41] The spectacle became a popular touring exhibition.[42][43] In the late 1930s, sportswriter Damon Runyon persuaded Seltzer to change the Roller Derby rules to increase skater contact.[41] By 1939, after experimenting with different team and scoring arrangements, Seltzer's created a touring company of four pairs of teams (always billed as the local "home" team versus either New York or Chicago),[44] with two five-person teams on the track at once, scoring points when its members lapped opponents.[45]

Television

On November 29, 1948, before television viewership was widespread, Roller Derby debuted on New York television.[46]: 89 The broadcasts increased spectator turnout for live matches.[47] For the 1949–1950 season, Seltzer formed the National Roller Derby League (NRDL), comprising six teams.[48][46]: 95 NRDL season playoffs sold out Madison Square Garden for a week.[48] During the late 1950s and 1960s, the sport was broadcast on several networks, but attendance declined. Jerry Seltzer (Leo's son), the Roller Derby "commissioner", hoped to use television to expand the live spectator base. He adapted the sport for television by developing scripted story lines and rules designed to improve television appeal, but derby's popularity had declined.[46]

1989 saw the debut of RollerGames, an even more theatrical variant of roller derby for national audiences. It used a figure-8 track and rules adapted for this track. Bill Griffiths, Sr. served as commissioner while his son, Bill Griffiths, Jr., managed the L.A. T-Birds, who (according to the storyline) were seeking revenge on the Violators (led by Skull) for cheating in the Commissioner's Cup. The other teams included the Maniacs (led by Guru Drew), Bad Attitude (led by Ms. Georgia Hase), the Rockers (led by DJ Terringo and consisting of skaters who were also professional rock and roll musicians), and Hot Flash (led by Juan Valdez Lopez). It ran one season, because some of its syndicators went bankrupt.

In 1999, TNN debuted RollerJam, which used the classic rules and banked oval track, but allowed inline skates (although some skaters wore traditional quad skates). Jerry Seltzer was commissioner for this version.

Contemporary roller derby

Amateur revival

.jpg.webp)

Roller derby began its modern revival in Austin, Texas in the early 2000s as an all-female, woman-organized amateur sport.[50] By August 2006, there were over 135 similar leagues.[51] Leagues outside the U.S. also began forming in 2006, and international competition soon followed. There are over 2,000 amateur leagues worldwide[52] in countries including Canada, Australia, New Zealand, the United Kingdom, France,[53] Brazil, Germany, Belgium, Finland, Norway,[54] Sweden,[55] Denmark,[56] Israel,[57] Singapore,[58][59][60] UAE,[61][62] Egypt,[63][64][65] Thailand,[66] and China.[67] In many international leagues, gear and equipment must be imported.[68] Roller derby's contemporary resurgence has been regarded as an aspect of globalization which demonstrates "the speed with which pop culture is now transported by highly mobile expatriates and social media, while also highlighting the changing role of women in many societies".[2]

Many roller derby leagues are amateur, self-organized and all-female[69] and were formed in a do-it-yourself spirit by relatively new enthusiasts.[70] In many leagues (especially in the U.S.), a punk[71][72] aesthetic and/or third-wave feminist[73] ethic is prominent.[74] Members of fledgling leagues often practice and strategize together, regardless of team affiliation, between bouts.[75] Most compete on flat tracks, though several leagues skate on banked tracks, with more in the planning stages.[76]

Each league typically features local teams in public bouts that are popular with a diverse fan base.[77] Some venues host audiences ranging up to 7,000.[78] Successful local leagues have formed traveling teams comprising the league's best players to compete with comparable teams from other cities and regions. In February 2012, the International Olympic Committee considered roller derby, amongst eight other sports, for inclusion in the 2020 Olympic Games.[79][80]

In 2009, the feature film Whip It featured roller derby and introduced a wider audience to the sport. The WFTDA encouraged leagues to coordinate with promotions during the film's release to increase awareness of the leagues.[81] Furthermore, corporate advertising has used roller derby themes in television commercials for insurance,[82] a breakfast cereal,[83] and an over-the-counter analgesic.[84]

Derby names

-1005.jpg.webp)

| Name | Allusion |

|---|---|

| Guinefear of Jamalot | Guinevere of Camelot |

| Mazel Tov Cocktail | Mazel tov, Molotov cocktail |

| O Hell No Kitty | Hello Kitty |

| Sandra Day O'Clobber | Sandra Day O'Connor |

| Punky Bruiser | Punky Brewster |

| Roly Mary Mother of Quad | Holy Mary Mother of God |

| Ania Marx | On Your Marks |

| Princess Lay-Ya Flat | Princess Leia |

| Anna Mosity | Animosity |

| Smack Ops | Black Ops |

| Cactus Rack | Cactus Jack, a persona of retired professional wrestler Mick Foley |

| Trauma Queen | Drama Queen |

| Bonnie Thunders | Johnny Thunders |

Most players in roller leagues skate under pseudonyms, also called "derby names" or "skater names". These typically use word play with satirical, mock-violent or sexual puns, alliteration, and allusions to pop culture. Referees often use derby names as well,[86] often shown on the backs of their striped uniforms. Some players claim their names represent alter egos that they adopt while skating.[87]

Whether a team should skate under real names or derby names is sometimes debated.[88] Some derby names are obscene, a subject of some internal controversy.[89]

Copying of derby names has attracted legal and sociological analysis as an example of indigenous development of property rights.[11] New players are encouraged to check derby names against an international roster to ensure they are not already in use.[85][90]

The names of roller derby events are also as sardonic and convoluted—for example, Night of the Rolling Dead (Night of the Living Dead), Knocktoberfest (Oktoberfest), Spanksgiving (Thanksgiving), Seasons Beatings (Seasons Greetings), Grandma Got Run Over By a Rollergirl ("Grandma Got Run Over by a Reindeer"), Cinco de May-hem (Cinco de Mayo), and War of the Wheels (War of the Worlds).[91]

Safety

Roller derby is a contact sport, and injuries can occur. Superficial injuries include bruising.[92] However, torn ligaments, broken bones, and concussions also occur.[93][94][95]

Some leagues prominently display their injuries, to embellish the image of violence or machismo.[96][97] However, some skaters say the sport is reasonably safe if skaters take precautions.[98] The rules require appropriate medical professionals on-site at every bout,[1]: 39 even if not required by laws or arena regulations. The WFTDA offers insurance for leagues in the United States with legal liability and accident coverage, but it recommends that skaters also carry their own primary medical insurance.[99]

Expansion

Although the early 2000s revival of roller derby was initially all-female, some leagues later introduced all-male teams and all-gender games; as of May 2013 there were over 140 junior roller derby programs in the United States, and many more around the world.[100]

College roller derby is also expanding in the United States. The University of Arizona's Derby Cats describe themselves as the first-ever official college flat-track roller derby team.[101] The first intercollegiate derby bout took place on March 3, 2018, when the Claremont Colleges roller derby team defeated Arizona State University.[102]

The website FlatTrackStats compiles ratings of WFTDA teams, adjusting them after every bout based on how the actual score compares to the predicted score. The WFTDA's own Stats Repository has comparable information and often is updated at halftime of a bout.[103]

Roller derby bouts are now streamed online, and there are archived videos of past bouts and tournaments. The WFTDA offers live streaming video of its tournaments at wftda.tv. Derby News Network offered live streaming video and archived video including events outside the WFTDA.

FiveOnFive magazine covers roller derby and diverse aspects such as business, training, junior roller derby, and nutrition.[104]

Governance and organization

The largest governing body for the sport is the Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA), with 397 full member leagues and 48 apprentice leagues.[12] WFTDA membership is a major goal of aspiring leagues.[105] Other associations support either coed or men-only derby; the largest organization supporting male roller derby is the Men's Roller Derby Association (MRDA).[106][107][108] Within the United States, the Junior Roller Derby Association governs play by those under 18. It modifies the WFTDA rules for minors, such as prohibiting hitting and accelerating into a block.[109] Some U.S. leagues decline affiliation with a national organization because they prefer local governance.[110][111]

Although WFTDA has been the largest worldwide roller-derby organization, the IOC has recognized World Skate (formerly Fédération Internationale de Roller Sports) as the only governing body able to sanction international roller derby competitions within the Olympic Movement. Disputes between World Skate and WFTDA has meant that only 4 teams were present in the first Roller Derby World Championships organized by World Skate in 2017, as part of the 2017 World Roller Games[112]

USA Roller Sports (USARS) is recognized by the International Roller Sports Federation (FIRS) and the United States Olympic Committee (USOC) as the National Governing Body of competitive roller sports in the United States, including speed, figure, hockey, roller derby and slalom. WFTDA and USARS maintain a reciprocity agreement for insurance purposes.[113]

Outside the United States, many roller derby leagues enjoy support from their national skate federations, such as Skate Australia,[114] the British Roller Sports Federation,[115] and Roller Sports Canada.[116] In Europe, roller derby was recognized as a sport in Paris in 2010 by the Federation Internationale de Roller Sports (FIRS), which reports directly to the International Olympic Committee. As of 2017, FIRS has been accepted as the international rule set by the International Olympic Committee. Teams competed under the FIRS rules at the 2017 Nanjing Games.[117] The former Canadian Women's Roller Derby Association worked with the American federation.[118]

Tournaments

Since 2006, the WFTDA has sponsored an annual championship. In 2008, it adopted the "Big 5" format: four regional playoffs and a final championship tournament.[119] As of 2019, the WFTDA postseason includes two playoffs that feed into the Championship tournament, plus three standalone, regionally-based Continental Cups.[120] The WFTDA also recognizes eligible tournaments hosted by member leagues.[121]

Internationally, the first Roller Derby World Cup took place in Toronto, Canada, in December 2011.[122] The second World Cup took place in Dallas, Texas, in December 2014.[123]

Since 2012, USARS has held an annual Roller Derby National Championship. In 2017, FIRS and the USOC recognized USARS to participate in the 2017 Nanjing games.[117]

The largest roller derby tournament in the southern hemisphere, The Great Southern Slam, has been held biannually in Adelaide, South Australia since 2010.

Social significance

Zaina Arafat said in the Virginia Quarterly Review that roller derby defies heteronormativity and patriarchal standards. In Egypt, Arafat says, there are expectations that a woman will not show visible scars, will have an unblemished body for her husband, and will refrain from activities that may damage her body. She says roller derby in Egypt is subversive, as it acts as an indirect political statement.[124]

Author Carly Giesler said that skaters enact sexualities that create or reclaim an identity, and their role parodies "hegemonic scripts of sexuality" through the use of costumes, derby names and personas. Roller derby acts as a unique stage for female athletes, letting them rebut constraints society places on women and female athletes. Giesler said that female sports objectifies them for the male gaze, but roller derby turns this on its head by disregarding gender roles and norms.[125]

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Until 2019, the jammer also scored a point by passing the opposing jammer. There were 5 potential points per trip.

- ↑ Before 2013, there were "major" and "minor" penalties, the former included any player's fourth penalty, and it was strategic for a key player to deliberately commit such a penalty when it would have least effect.

- ↑ "Roland Cloni of Akron, world's champion roller skater, who yesterday tried out the track in the Broadway armory, where the national roller skating derby will be held this week, asserted new world's records can be established for flat tracks. The derby will open tomorrow and run until Saturday."[38]

- ↑ Sources disagree on whether it was Leo alone or with his brother, the skate maker Oscar Seltzer.[39][40]

- ↑ "Roller derby has entertained the masses in one form or another since the 1930s, when brothers Leo and Oscar Seltzer conceptualized the idea of a skating contest on a Chicago restaurant tablecloth."[39]

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 29 30 31 32 33 34 35 36 37 38 39 40 41 42 43 44 45 46 "The Rules of Flat Track Roller Derby". Women's Flat Track Derby Association (WFTDA). Retrieved 2018-05-15.

- 1 2 Moffett, Matt (2013-02-03). "As the World Turns, So Do the Wheels of Roller Derby". Online.wsj.com. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "The Rules of Flat Track Roller Derby", Women's Flat Track Derby Association official site, 2023, retrieved March 21, 2023

- ↑ Clark, Brian J.; Spencer, L. Todd (2012). "Common Ground: the alternative sport of roller derby". YouTube. The Virginian-Pilot. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Roller Derby: The Fastest Growing Sport In America". YouTube. 2012-02-26. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Neale, Rick (24 June 2008). "All-Female Roller Derby Elbows Its Way In as a Legitimate Sport", USA Today

- ↑ "Will roller derby be included in the 2020 Olympics? | Olympics | Sports | National Post". Sports.nationalpost.com. 4 July 2011. Archived from the original on 20 July 2012. Retrieved 6 March 2012.

- ↑ "Roller Sports's pitch for the 2020 Olympics". Olympictalk.nbcsports.com. 2013-05-28. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ Greg Otto (2013-05-30). "Three Sports Make Olympic Cut for 2020 Summer Games". U.S. News. Archived from the original on 2017-08-15. Retrieved 2017-09-11.

- ↑ "SpudTown Knockdown 3: An Interview with CandyMan, Tournament Director | Fragglepuss". Fragglepuss.wordpress.com. 2012-08-29. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- 1 2 Fagundes, Dave (2011-03-15). "Talk Derby to Me: Intellectual Property Norms Governing Roller Derby Pseudonyms". SSRN 1755305.

- 1 2 "WFTDA Leagues". WFTDA. 2017. Retrieved 2017-07-08.

- ↑ "RDCL - Roller Derby Coalition of Leagues". Roller Derby Coalition of Leagues. Retrieved January 8, 2020.

- ↑ "DNN Releases First Power Rankings of 2010". Derby News Network. 2010-03-05. Archived from the original on 2011-12-01. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ↑ "Join Us". United Kingdom Roller Derby Association. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-10-04.

- ↑ "Welcome to CWRDA". Canadian Women's Roller Derby Association. Archived from the original on 2009-05-10. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ↑ "Derby 101". Canberra Roller Derby League. Retrieved 25 July 2012.

- 1 2 Em Dash (2016-04-22). "Learning to Pivot in Roller Derby". DerbyLife.com. Archived from the original on 2018-05-17. Retrieved 2018-05-16.

- ↑ "Roller derby: A glossary". Silicon Valley Roller Girls. 5 February 2009. Retrieved 2018-06-26.

- ↑ Brauns, Katie (2009-04-14). "A Local Roller Derby Team Shows Its Toughness at a Saturday Bout but Doesn't Get a Win". Bend Bulletin. Archived from the original on 2012-09-09. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- ↑ Vodoo, Big Daddy. "Roller Derby Strategies and Plays". Little City Roller Girs. Archived from the original on 2012-04-02. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ Joulwan, Melissa (2007-04-06). Rollergirl: Totally True Tales from the Track - p 94. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416538554.

- ↑ "Game Play: Strategy". Atlanta Roller Girls. Archived from the original on 28 September 2011. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ↑ Crouse, Tripp (15 July 2011). "Five Point Grand Slam: By the Position – Pivot/No. 1". Fivepointgrandslam.blogspot.com. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "Passing the Panty". Derbystein.wordpress.com. 9 August 2015. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ Bump, Speed. "Strategy 101: The Wall". Rose City Rollers. Archived from the original on 14 June 2018. Retrieved 22 September 2011.

- ↑ Lucy Croysdill. "Roller Derby Training: Evasive Jamming – Part One". pivotstar.com. Archived from the original on 2018-09-30. Retrieved 2018-09-29.

- ↑ Joulwan, Melissa (2007-04-06). Rollergirl: Totally True Tales from the Track - p 95. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 9781416538554.

- ↑ Ma, Ling (21 October 2010). "Game Changer". Chicago Reader. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ Falcon, M. "Derby Techniques of Interest Part 1: Knocking a jammer out of bounds and forming a bridge". Thunder Bay Roller Derby League. Archived from the original on 20 September 2016. Retrieved 23 August 2016.

- ↑ "Remarkable roller-skating feat". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1884-04-13. p. 10.

- ↑ "A six-day roller skate race". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1885-03-02. p. 10.

- ↑ "On rollers for six days: beginning the race at the Madison-Square Garden. Thirty-six entries, including Frank Hart and several champions—cheering the start". New York Times. 2 March 1885. p. 10.

- ↑ "Roller marathon thrills and jars: 100 boys meet with adventures and tumbles in West Side Boulevard race. Dodge cars and autos. But records are smashed by contestants in red tights, overalls, etc". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1908-11-27. p. 5.

- ↑ "Roller skating on banked track: old-time sport is revived with speed contests at the Garden". New York Times. 1922-12-17. p. 11.

- ↑ "24-hour roller race: Ollie Moore will be teamed with Willie Blackburn at Garden". New York Times. 1914-12-17. p. S2.

- 1 2 "Roller derby on tomorrow". Chicago Daily Tribune. 1922-04-24. p. 20.

- 1 2 Boulware, Jack (2000). San Francisco Bizarro: A Guide to Notorious Sights, Lusty Pursuits, and Downright Freakiness in the City by the Bay. Macmillan. p. 79. ISBN 0-312-20671-2.

- ↑ Luker, Kelly (1997-07-23). "Blood on the Tracks". Metro Santa Cruz. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- 1 2 Rasmussen, Cecilia (1999-02-21). "L.A. Then and Now: The Man Who Got Roller Derby Rolling Along". Los Angeles Times.

- ↑ "Roller Derby". Time. 1936-02-03. Archived from the original on March 14, 2009. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ "Variations". Time. 1936-09-21. Archived from the original on December 15, 2008. Retrieved 2008-07-13.

- ↑ Deford, Frank (1971). Five Strides on the Banked Track: The life and times of the Roller Derby. Little, Brown and Company. p. 84. ISBN 0-316-17920-5.

- ↑ "Roller Derby at the National Museum of Roller Skating". National Roller Skating Museum. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-02-22. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- 1 2 3 Deford, Frank (1971). Five Strides on the Banked Track: The Life and Times of the Roller Derby. Little, Brown and Company. ISBN 0-316-17920-5.

- ↑ Rushin, Steve (1998-12-14). "A Forward Roll: Dusted off and spiffed up, the Roller Derby is aiming to regain the hold it once had on TV". Sports Illustrated. Archived from the original on 2008-09-08. Retrieved 2018-04-24.

- 1 2 "Roller Derby". KTVU-TV. 2004. Archived from the original on 2007-04-05. Retrieved 2007-06-08.

- ↑ "USARS Rules of Roller Derby" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-03-24. Retrieved 2017-11-07.

- ↑ Brick, Michael (2008-12-17), "Pushing the Limit: The Dude of Roller Derby and His vision", New York Times, retrieved 2008-12-17

- ↑ La Gorce, Tammy (2008-11-07), "With Names That Could Kill, Women Rev Up Roller Derby", New York Times, retrieved 2008-12-17 (New York print edition: 2008-11-09 p. NJ6)

- ↑ "Teams - Roller Derby Stats & Rankings - Flat Track Stats". flattrackstats.com. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ "Paris, les filles et le Roller Derby (Paris Roller Girls)". YouTube. 2012-04-08. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Oslo Roller Derby". Retrieved 2013-01-30.

- ↑ Cat O'Ninetails (2011). "Roller Derby Worldwide". Retrieved 2011-09-08.

- ↑ "Copenhagen Roller Derby". Copenhagenrollerderby.com. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ TLV Derby Girls Archived 2014-07-14 at the Wayback Machine. Official site

- ↑ "Roller Derby Singapore". Roller Derby Singapore. Retrieved 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "New roller derby sport kicks off in Singapore". asiaone.com. 2011-12-19. Archived from the original on 2012-01-10. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ↑ "Roller Derby Singapore | CPDG | Teaser Video". YouTube. 2011-04-01. Archived from the original on 2021-11-07. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Dani (2012-10-13). "In the beginning". Dubai Roller Derby. Retrieved 2013-10-15.

- ↑ "21 sports in Dubai this week - Sport & Outdoor Features". TimeOutDubai.com. 2013-01-15. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Up Close and Personal with the CaiRollers of Cairo, Egypt". DerbyLife.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-28. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "Egypt's Cairollers Have Best Name Ever, Are Super Rad Rollergirls". Jezebel.com. 2012-11-27. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ "thoughts on the start of the 12th year of Modern Roller Derby « Jerry Seltzer". Rollerderbyjesus.com. 2013-01-18. Archived from the original on 2014-03-01. Retrieved 2013-02-15.

- ↑ Welle (www.dw.com), Deutsche, Top stories in 90 seconds | DW | 05.01.2022, retrieved 2022-01-05

- ↑ jknotts (2019-09-08). "Why Roller Derby is the Toughest Sport on Eight Wheels". www.thebeijinger.com. Retrieved 2022-01-05.

- ↑ "Cairollers Bring Roller Derby to Egypt". Dailynewsegypt.com. 13 March 2013.

- ↑ Whittaker, Richard. "Electric Skaterland: Austin births a Roller Derby revolution Austin Sports". AustinChronicle.com. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ The Dames: The Story of the Boston Roller Derby League (QuickTime). Cambridge, MA: Cambridge Community Television. 2008-02-22. Event occurs at 26:50. Retrieved 2008-06-23. See also the accompanying blog post Archived 2008-05-01 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ Wells, Steven (2005-05-23). "Roller derby gets a good punking". The Guardian. London.

- ↑ "Punk On The Rocks: Roller Derby Wrecker". Ourstage.com. Archived from the original on 2012-03-31.

- ↑ Jackie (2006-10-26), Roller Derby: Uniting Younger Women, One Bout at a Time, Younger Women's Task Force, retrieved 2008-06-18 (This is a post on the main YWTF blog.)

- ↑ Pat Zanghi (2010-04-22). "Oddballs: Roller Derby". Uncle Boise. Archived from the original on 2010-05-28. Retrieved 2009-05-25.

- ↑ "Soldiers in the Roller Derby". Army Live.

- ↑ "Reno Roller Girls". Reno Roller Girls. Archived from the original on 2011-02-02. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ "WFTDA 2011 Demographic Survey Results". WFTDA. Archived from the original on 2011-04-02. Retrieved 2011-03-31.

- ↑ "New Jersey Roller Derby packs thousands into Convention Hall - Video - NJ.com". Videos.nj.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-07. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ Van, Samantha. "Roller Derby May Be Included in 2020 Olympics: A Female's Reaction". Sports.yahoo.com. Archived from the original on 2013-03-16. Retrieved 2012-03-06.

- ↑ "CNN.com Video". CNN.

- ↑ Loca, Chica. "Whip It-Marketing Session" (PDF). WFTDA. Archived from the original (PDF) on 20 August 2012. Retrieved 24 September 2011.

- ↑ "Shannon and Heather's aha moment commercial - YouTube". www.YouTube.com. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Cheerios TV ad on YouTube

- ↑ Aleve TV ad on YouTube

- 1 2 King, April, ed. (2014-09-01). "International Rollergirls' Master Roster". twoevils.org. Retrieved 2018-06-17.

- ↑ Tracy "Justice Feelgood Marshall" Williams (2008-12-08), Killbox retires (sort of), Derby News Network, archived from the original on 2010-12-25, retrieved 2008-12-30

- ↑ "Seattle Derby Brats – No Flash in the Pan". Archived from the original on 2011-01-24. Retrieved 2010-08-23.

It's like your alter ego," Grianne says, "You don't want to be announced as Grianne Hunter. You want to be something tougher.

- ↑ "Denver Roller Dolls—Teams—Mile High Club". Retrieved 2009-07-19.

This season, 13 of the team's members are making the switch from derby names to real names.

- ↑ "Derby Names: Not Ready for Prime Time". DerbyLife.com. 2011-09-14. Archived from the original on 2011-10-02. Retrieved 2011-09-24.

- ↑ Derby Roll Call Archived 2018-08-21 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ "Treasure Valley Rollergirls". Treasure Valley Rollergirls. Archived from the original on 2011-07-24. Retrieved 2010-08-31.

- ↑ Wilson, Tracy (2005-11-07), How Roller Derby Works, HowStuffWorks, Inc., retrieved 2008-06-22

- ↑ "Anatomy of a concussion". NJ.com. 2008-11-20. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "Dain Bramage". Roller Derby. Archived from the original on 2011-11-01. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ Ryder, Kari (2008-06-19). "PCL Injuries in Roller Derby". Retrieved 2008-06-22.

- ↑ Injury Gallery, Rat City Rollergirls, archived from the original on 2007-10-26, retrieved 2008-06-22

- ↑ Pabst Bruise Gallery, Minnesota RollerGirls, archived from the original on 2007-08-14, retrieved 2008-06-22

- ↑ "Derby injuries? - SkateLog Forum". Skatelogforum.com. Archived from the original on 2016-03-03. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "WFTDA Insurance Program". WFTDA. Retrieved 2018-06-18.

- ↑ "Roller Derby Worldwide". Archived from the original on 2013-01-11. Retrieved 2013-05-01.

- ↑ Looser, Devoney (2014-05-02). "Could Roller Derby Be the Brighter Future of College Sports?". Slate Magazine. Retrieved 2019-10-22.

- ↑ Patel, Rena (2018-03-28). "5C Roller Derby Team Victorious Against ASU in First Ever Intercollegiate Derby Bout on the West Coast". The Scripps Voice. Retrieved 2022-09-24.

- ↑ "WFTDA Stats Actually Rule". The Derby Apex. 2017-05-18.

- ↑ "fiveonfive » women's flat track roller derby magazine". Fiveonfivemag.com. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ Dator, James (13 August 2013). "The rise of roller derby". SBNation.com. Retrieved 2016-03-01.

- ↑ "The State of Derby – Part II: OSDA and JRDA". Archived from the original on 2011-08-25. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ "The State of Derby – Part III: Modern Athletic Derby Endeavor". Rollerderbyinsidetrack.com. Archived from the original on 2011-09-05. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ Captain Gorgeous (2011-06-28). "The State of Derby – Part IV: Men's Roller Derby Association". Roller Derby Inside Track. Archived from the original on 2011-09-15. Retrieved 2011-10-06.

- ↑ "HOME". Junior Roller Derby Association. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ USA Roller Sports. "To Whom It May Concern" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-10-26.

- ↑ "Open Letter to USA Roller Sports". Women's Flat Track Derby Association. 2011-05-12. Archived from the original on 2011-10-10. Retrieved 2012-02-04.

- ↑ "FIRS unveils 1st edition of international Roller Derby rules". rollerderbynotes.com. 30 December 2016. Retrieved 2023-04-11.

- ↑ "USARS / WFTDA Reciprocity". USA Roller Sports. 2009-06-24. Archived from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ↑ Rachel Afflick. "Ballarat Junior Roller Derby Star Set for Battle". Archived from the original on 2011-10-07. Retrieved 2011-10-05.

- ↑ "Roller Derby is now recognised as a sport in the UK, and UKRDA the National Association". Euroderby.org. Retrieved 2011-10-02.

- ↑ "Roller Derby". Rollersports.ca. 2010-01-07. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- 1 2 "Rolling Up to Tokio 2020". Rollersports.org. Retrieved 2017-11-01.

- ↑ "Welcome to the CWRDA". Roller Derby Association of Canada. Archived from the original on 2011-10-26. Retrieved 2011-10-12.

- ↑ "THE BIG 5 WFTDA SPONSORED TOURNAMENTS". WFTDA. Archived from the original on 2011-11-15. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ↑ "2019 WFTDA Postseason Dates and Locations Released". WFTDA. 1 March 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ↑ "WFTDA Recognized Events". WFTDA. Retrieved 2011-11-15.

- ↑ "Blood & Thunder Roller Derby World Cup 2011". Blood & Thunder Magazine. Archived from the original on 2011-08-12. Retrieved 2011-08-08.

- ↑ "Dallas to Host 2014 Roller Derby World Cup". Blood & Thunder Magazine. 2013-06-10. Archived from the original on 2014-12-14. Retrieved 2014-12-14.

- ↑ Arafat, Zaina, "POWER JAM: Roller Derby as Political Act", Virginia Quarterly Review, vol. 93, no. 3, Summer2017, pp. 36-59.

- ↑ Gieseler, Carly. "Derby Drag: Parodying Sexualities in the Sport of Roller Derby". Sexualities, vol. 17, no. 5-6, 2014, pp. 758–776., doi:10.1177/1363460714531268.

External links

- The Rules of Flat Track Roller Derby (WFTDA), with illustrations and case rulings; links for PDF and single-web-page formats

- Roller derby at Curlie

- Flat Track Stats—Statistical aggregation of WFTDA sanctioned roller derby

- Roller Derby Forum