| |

| Classification | |

|---|---|

| Related instruments | |

| Arbajo, Dotara, Dranyen, Pamiri rubab, Seni rebab, Sarod, Tungna, Dutar, Tanbur | |

Rubab, Robab or Rabab (Pashto / Persian: رُباب, Punjabi: ਰਬਾਬ, Kashmiri: رَبابہٕ, Sindhi: روباب (Nastaleeq), रबाब (Devanagari), Azerbaijani / Turkish: Rübab, Tajik / Uzbek рубоб) is a lute-like musical instrument.[1] The rubab, one of the national musical instruments of Afghanistan, is also commonly played in Pakistan and India by Pashtuns, Balochis, Sindhis, Kashmiris[2] and Punjabis. The rubab has three variants, the Kabuli rebab of Afghanistan, the Rawap of Xinjiang, the Pamiri rubab of Tajikistan and the seni rebab of northern India.[3] The instrument and its variants spread throughout West, Central, South and Southeast Asia.[4] The Kabuli rebab from Afghanistan[1] derives its name from the Arabic rebab and is played with a bow while in Central Asia and the Indian subcontinent, the instrument is plucked and is distinctly different in construction.[3]

Size variants

| English | Strings | Pashto | Persian | In Inches |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Small | 5 sympathetic strings | وړوکی رباب

Warukay Rabab |

زيلچه

Zaliche |

27 |

| Medium | 19 strings, 13 sympathetic strings | منځنۍ) رباب)

(Mianzanai) rabab |

رباب

Rubab |

28 |

| Large | 21 strings, 15 sympathetic strings | لوی رباب

Large rabab |

شاه رباب (king size)

Shah rabab |

30 |

Components

_ca_1200_CE.jpg.webp)

| English | Pashto | Persian |

|---|---|---|

| Headstock | تاج

Tāj |

سرپنجه or تاج

"Tāj" or "Sar Penjah" |

| Tuning peg | غوږي

Ghwagi/Ghwazhi |

گوشی

Goshi/Gushi |

| Nut | ? | شیطانک

Sheitanak |

| Neck | غړۍ

Gharai |

دسته

Dastah |

| Strings | تارونه

Tāruna |

تار

Tār |

| Long/Low Drones | شاتار

Shātār |

شاهتار

Shahtar |

| Short/High Drones | ? | ? |

| Sympathetic Strings | بچي

Bachi |

? |

| Frets | پرده

Pardah |

پرده

Pardah |

| Chest | سينه

Sinah |

سینه

Sinah |

| Side | ? | صفحه

Safhah |

| Skin belly | ګوډی or څرمن

"Tsarman" or "Goday" |

پوست

Pust |

| Head or Chamber | ډول

Dol |

کاسه

Kasah |

| Bridge | ټټو

Tatu |

خرک

Kharak |

| tailpiece | ? | سیمگیر

Seemgeer |

| Plectrum | شاباز

Shabaz |

مضراب

Mezrab |

In detail about the strings:

| English | Explanation | Pashto | Persian |

|---|---|---|---|

| Strings | Main strings: 3 and made out of nylon

Long Drone: 2-3 and made out of steel Short Drone: 2 and made out of steel |

تارونه

Tāruna |

تار

Tār |

| First/Low/Bass String | Low/Bass String is the thickest string | کټی

Katay |

? |

| Second String | Thiner than bass string and thicker than high string | بم

Bam |

بم

Bam |

| Third/High String | The thinest string out of all the three main strings | زېر

Zer |

زیر

Zir |

Construction

The body is carved out of a single piece of wood, with a head covering a hollow bowl which provides the sound-chamber. The bridge sits on the skin and is held in position by the tension of the strings. It has three melody strings tuned in fourths, two or three drone strings and up to 15 sympathetic strings. The instrument is made from the trunk of a mulberry tree, the head from an animal skin such as goat, and the strings from the intestines of young goats (gut) or nylon.

History

The rubab is known as "the lion of instruments" and is one of the two national instruments of Afghanistan (with the zerbaghali).[3] Classical Afghan music often features this instrument as a key component. Elsewhere it is known as the Kabuli rebab in contrast to the Seni rebab of India.[3] In appearance, the Kabuli rubab looks slightly different from the Indian rubab.[5] It is the ancestor of the north Indian sarod, although unlike the sarod, it is fretted.[6]

The rubab is attested from the 7th century CE. It is mentioned in old Persian books, and many Sufi poets mention it in their poems. It is the traditional instrument of Khorasan and is widely used in countries such as Afghanistan, Pakistan, Azerbaijan, Iran, Turkey, Iraq, Tajikistan, and Uzbekistan, as well as in the Xinjiang province of northwest China and the Jammu and Kashmir and Punjab regions of northwest India.[7]

The rubab was the first instrument used in Sikhism; it was used by Bhai Mardana, companion of the first guru, Guru Nanak. Whenever a shabad was revealed to Guru Nanak he would sing and Bhai Mardana would play on his rubab; he was known as a rababi. The rubab playing tradition is carried on by Sikhs such as Namdharis.

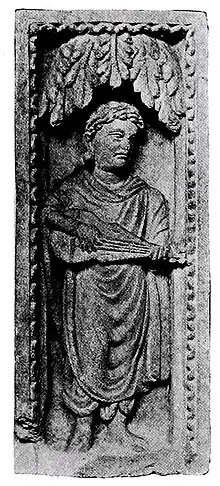

Young man with Iranian rubab, 16th century, Safavid Empire. 8-shaped body resembles a tar, but tars have both sides of the 8 covered with hide. Rubabs had a lower section covered with hide, and an upper hollow section covered with wood.

Young man with Iranian rubab, 16th century, Safavid Empire. 8-shaped body resembles a tar, but tars have both sides of the 8 covered with hide. Rubabs had a lower section covered with hide, and an upper hollow section covered with wood. Abbasid era rubab, painted on the inside of a bowl, 10th century C. E. The instrument has two strings.

Abbasid era rubab, painted on the inside of a bowl, 10th century C. E. The instrument has two strings.

Variants

_titled_'Lute_Players_Near_the_Golden_Temple'%252C_taken_on_28_January_1903.jpg.webp)

In northern India, the seni rebab, which emerged during the Mughal Empire, has "a large hook at the back of its head, making it easier for a musician to sling it over the shoulder and play it even while walking."[3] The Sikh rabab was traditionally a local Punjabi variant known as the 'Firandia' rabab (Punjabi: ਫਿਰੰਦੀਆ ਰਬਾਬ Phiradī'ā rabāba),[8][9][10][11] however Baldeep Singh, an expert in the Sikh musical tradition, challenges this narrative.[12][13]

In Tajikistan a similar but somewhat distinct rubab-i-pamir (Pamiri rubab) is played, employing a shallower body and neck.[14] The rubab of the Pamir area has six gut strings, one of which, rather than running from the head to the bridge, is attached partway down the neck, similar to the fifth string of the American banjo.[15]

Notable players

- Ustad Mohammed Omar (1905—1980), Rabab player From Kabul, Afghanistan

- Ustad Rahim Khushnawaz (1945-2010), Rabab Player From Herat, Afghanistan

- Ustad Homayun Sakhi, Rabab Player From Kabul, Afghanistan

- Ustad Ramin Saqizada, Rabab Player From Afghanistan

- Ustad Sadiq Sameer, Rabab Player, From Afghanistan

- Ustad Shahzaib Khan, Rabab Player From Nowshera/Nokhar, Pakistan

- Ustad Waqar Atal, Rabab Player, From Peshawer, Pakistan

- John Baily, Emeritus Professor of Ethnomusicology at Goldsmiths, University of London [16]

- Khaled Arman (b. 1965), Rabab Player and Guitarist From Kabul, Afghanistan [17]

- Daud Khan Sadozai, Afghan Rubab and Sarod Player from Kabul Afghanistan [18]

See also

References

- 1 2 David Courtney, 'Rabab', Chandra & David's Homepage

- ↑ The Wide World Magazine: An Illustrated Monthly of True Narrative, Adventure, Travel, Customs and Sport ... A. Newnes, Limited. 1905. pp. 15–.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "The roar of Afghan's 'lion of instruments'". Deccan Herald. 10 April 2016. Retrieved 16 August 2021.

- ↑ Miner, Allyn (2004). Sitar and Sarod in the 18th and 19th Centuries. Motilal Banarsidass Publications. p. 61. ISBN 9788120814936.

- ↑ Kak, Siddharth (1982). Cinema Vision India, Volume 2. Siddharth Kak. p. 25.

The rubab of Kabul is very similar to the sarod. The Indian rubab looks different. The sarod is a blend of these two rubabs.

- ↑ Simon Broughton. "Tools of the Trade: Sarod". Songlines-The World Music Magazine. Archived from the original on 2006-11-18.

- ↑ "Indian Music : Indian Instruments". Archived from the original on 2017-10-24. Retrieved 2017-10-23.

- ↑ "Rabab". Sikh Musical Heritage - The Untold Story. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ↑ "Raj Academy | Rabab". Raj Academy. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ↑ "Rabab". SIKH SAAJ. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ↑ "Sikh Instruments-The Rabab". Oxford Sikhs. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ↑ Bharat Khanna (Nov 1, 2019). "Punjabi varsity's Firandia rabab helps revival of string instrument | Ludhiana News - Times of India". The Times of India. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ↑ Singh, Baldeep (2012-06-27). "Rabab goes shopping…". The Anād Foundation. Retrieved 2022-08-18.

- ↑ "Pastimes of Central Asians. A Musician Playing a Rubab, a Fretted Lute-like Instrument". World Digital Library. Retrieved 14 May 2014.

- ↑ Music and Poetry from the Pamir Mountains Musical Instruments, The Institute of Ismaili Studies.

- ↑ "Professor John Baily". Goldsmiths, University of London.

- ↑ "Biography". Khaled Arman.

- ↑ "Biography". www.daud-khan.art. Retrieved 2021-05-19.

External links

- Video, rubab being played. Part of performance is slide rubab, like slide guitar.

- Existence of rubab threatened in modern Afghanistan.

- Will the Taliban Stop the Music in Afghanistan?

- Farabi School

- World Music Central - Ustad Mohammad Omar

- Music of the Uyghurs