.JPG.webp)

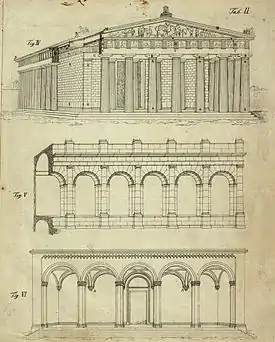

Rundbogenstil (round-arch style) is a nineteenth-century historic revival style of architecture popular in the German-speaking lands and the German diaspora. It combines elements of Byzantine, Romanesque, and Renaissance architecture with particular stylistic motifs.[1] It forms a German branch of Romanesque Revival architecture sometimes used in other countries.

History and description

The style was the deliberate creation of German architects seeking a German national style of architecture, particularly Heinrich Hübsch (1795–1863).[2][3][4] It emerged in Germany as a response to and reaction against the neo-Gothic style that had come to the fore in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. By adopting the smooth facade of late antique and medieval church architecture, it aimed to extend and develop the noble simplicity and quiet grandeur of neo-classicism, while moving in a direction more suited to the rise of industrialism and the emergence of German nationalism. Hallmarks of the style, in addition to the rounded arches from which it takes its name, include "eyebrows" over the windows and inverted crenelation under the eaves.

Rundbogenstil was employed for a number of railway stations, including those in Karlsruhe, Leipzig, Munich, Tübingen, and Völklingen. These were typically "first-generation" stations (built between 1835 and 1870); some were razed to be replaced by larger buildings. Those in Tübingen and Völklingen are still extant, while the Bayerischer Bahnhof in Leipzig is partially preserved.

Rundbogenstil was also widely employed in synagogue architecture. The first in this style was the Kassel Synagogue designed by Heinrich Hübsch with Albrecht Rosengarten, built in the latter's native city, Kassel, Hesse-Kassel, in 1839.[5] An early example in the United States is the Gates of Heaven Synagogue in Madison, Wisconsin, built in 1863 and designed by August Kutzbock, an immigrant from Bremen, Germany. Kutzbock also (co)designed secular buildings employing Rundbogenstil, such as the Carrie Pierce House (1857) in Madison. It was restored in 2008 and adapted for use as a boutique hotel, known as the Mansion Hill Inn.

Rundbogenstil architecture was influential in England, with Alfred Waterhouse's buildings for what is now called the Natural History Museum (originally the British Museum Natural History Collection) in London showing a direct and self-conscious emulation of the style.[6]

Rundbogenstil German synagogues

Berlin Lindenstrasse (1890–91)

Berlin Lindenstrasse (1890–91) Berlin Rykestrasse (1904)

Berlin Rykestrasse (1904) Deidesheim (1854)

Deidesheim (1854) Ermreuth

Ermreuth Freiburg (1870)

Freiburg (1870) Friedrichstadt (1845)

Friedrichstadt (1845).JPG.webp) Hechingen (1850–52; facade 1881)

Hechingen (1850–52; facade 1881) Kassel (1839)

Kassel (1839) Kraków am See (1866)

Kraków am See (1866) Laufersweiler (1839)

Laufersweiler (1839) Meisenheim (1866)

Meisenheim (1866) Steinsfurt (1893)

Steinsfurt (1893)

Rundbogenstil German train stations

Crimmitschau (1873)

Crimmitschau (1873) Hersfeld (1883)

Hersfeld (1883) Minden (1847)

Minden (1847) Munich (1849)

Munich (1849)

Rundbogenstil architecture in New York City

Morse Building on Nassau Street, Manhattan (1878–80)

Morse Building on Nassau Street, Manhattan (1878–80)_Pct_153_E67_jeh.jpg.webp) 19th Precinct, 153 East 67th Street, Manhattan

19th Precinct, 153 East 67th Street, Manhattan

Paul Robeson Theater, formerly the Fourth Universalist Church, Fort Greene, Brooklyn (1833–34)

Paul Robeson Theater, formerly the Fourth Universalist Church, Fort Greene, Brooklyn (1833–34) French Evangelical Church, formerly the Catholic Apostolic Church, 126 West 16th Street, Manhattan (c.1865)

French Evangelical Church, formerly the Catholic Apostolic Church, 126 West 16th Street, Manhattan (c.1865) First Reformed Church, rebuilt 1859, Jamaica, Queens

First Reformed Church, rebuilt 1859, Jamaica, Queens

Rundbogenstil architecture in Hungary

Csokonai Theatre, Debrecen

Csokonai Theatre, Debrecen

Rundbogenstil-influenced architecture in England

Rundbogenstil in Belgium

The Rundbogenstil was also widely employed in Belgium, for public buildings as well as for churches. A keen promotor of Neoclassiscism and the Rundbogenstil in Belgium was architect Lodewijk Roelandt (1786-1864), who lived in the city of Ghent. Among his achievements in Rundbogenstil are St Anne's Church (Sint-Annakerk (Gent)), the riding school Arena Van Vletingen, both in Ghent, and the Onze-Lieve-Vrouw-van-Bijstand-der-Christenenkerk (Sint-Niklaas) at Sint-Niklaas.

See also

References

Notes

- ↑ Strauss, Gerhard & Olbrich, Harald: "Eintrag Rundbogenstil." Lexikon der Kunst. Architektur, bildende Kunst, angewandte Kunst, Industrieformgestaltung, Kunsttheorie. (in German.) Leipzig: Seemann. Band 6, p. 293 ff.

- ↑ Bergdoll, Barry, European Architecture, 1750-1890, Oxford, 2000, pp. 184-9

- ↑ Kathleen Curran, The Romanesque Revival: Religion, Politics, and Transnational Exchange, Penn State Press, 2003, p. 1 ff.

- ↑ James Stevens Curl, "Rundbogenstil", A Dictionary of Architecture and Landscape Architecture, 2000, Encyclopedia.com

- ↑ Rachel Wischnitzer, The Architecture of the European Synagogue, Philadelphia: JPS, 1964, pp. 197-8

- ↑ Records of HM Office of Works, P.R.O., Works 17/16/2, National Archives, 4 March 1868.

External links

Media related to Rundbogenstil architecture at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Rundbogenstil architecture at Wikimedia Commons