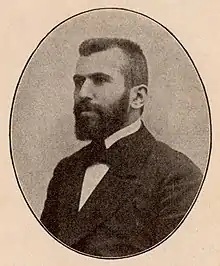

Süleyman Nazif | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 January 1870 Diyarbakır, Ottoman Empire |

| Died | 4 January 1927 (aged 56) Istanbul, Turkey |

| Nationality | Turkish |

Süleyman Nazif (Ottoman Turkish: سلیمان نظیف; 29 January 1870 – 4 January 1927)[1] was a Turkish poet and a prominent member of the CUP. He mastered Arabic, Persian, and French languages and worked as a civil servant during the reign of Sultan Abdul Hamid II. He contributed to the literary magazine Servet-i Fünun ("Wealth of Knowledge") until it was censored by the Ottoman government in 1901.[2]

Biography

Süleyman Nazif was born in 1870 in Diyarbakır to a Kurdish family, his father was Said Pasha, a poet and historian.[3] He was the brother of renowned Turkish poet and politician Faik Ali Ozansoy. He started his education in his very early years in Maraş. Later, he was schooled in Diyarbakır. In 1879, he joined his father again in Maraş, took private lessons from his father and in French language from an Armenian priest.[4]

Following the death of his father in 1892, Süleyman Nazif worked at several posts in the Governorate of Diyarbakır. In 1896, he was promoted and worked a while in Mosul. After moving to Constantinople, he started to write articles against Sultan Abdul Hamid II sympathizing with the ideas and aims of the Young Ottomans. He left Istanbul and settled in Paris in 1897.[5] There he contributed to Meşveret which had been started by Ahmet Rıza and joined the Committee of Union and Progress.[5] He stayed eight months in Paris.[4]

When he returned home, he was forced to work at a secretary post in the Governorate of Bursa. In 1908, Süleyman Nazif moved to Istanbul again and joined the Committee of Union and Progress. He also published a newspaper, Tasvîr-i Efkâr, together with the renowned journalist Ebüzziya Tevfik. Although this newspaper had to close soon, his articles made him a well-known writer.[2][4]

After Sultan Abdülhamid II restored the constitutional monarchy following the 1908 Young Turk Revolution, Süleyman Nazif served as governor of Ottoman provinces Basra (1909), Kastamonu (1910), Trabzon (1911), Mosul (1913) and Baghdad (1914).[6] However, since he was not very successful in administrative posts, he decided in 1915 to leave public service and return to his initial profession as a writer.[4]

During the Armenian genocide, Nazif was instrumental in preventing massacres from occurring in the province of Baghdad. In one instance, Nazif had intercepted a convoy of deportees numbering 260 Armenian women and children who were being sent to their deaths.[7] Nazif demanded that the convoy be transferred to a safer zone in Mosul but his proposal was ultimately refused. The convoy was eventually massacred.[7] During his time as governor of Baghdad, Nazif visited Diyarbakir where he encountered a "pungent smell of decaying corpses" which "pervaded the atmosphere and that the bitter stench clogged his nose, making him gag."[8] Nazif was critical of Dr. Mehmed Reshid, the governor of Diyarbakir, who was known as the "Butcher of Diyarbakir".[9] Nazif, who stated that Reshid "destroyed through massacre thousands of humans" also wrote about a committee established by Reshid with the objective of providing a 'solution of the Armenian question'.[8][10] The committee had its own military unit and was called the 'Committee of Inquiry'.[8] Nazif also encouraged other governors not to proceed with the deportation order. In a letter written to his brother Faik Ali Bey, the governor of Kutahya, Nazif wrote, "Don't participate in this event, watch out for our family's honor."[11]

On November 23, 1918, Nazif's article titled Kara Bir Gün (literally: A Black Day) was published in the newspaper Hadisat to condemn the French occupying forces in Istanbul. The article led to the commander of the French forces sentencing Nazif to execution by firing squad. The order was rescinded, however. As a result of a speech he gave on January 23, 1920, at a meeting to commemorate the French writer Pierre Loti, who had lived a while in Constantinople, Süleyman Nazif was forced into exile on Malta by the occupying British military. During his stay of around twenty months in Malta, he wrote the novel Çal Çoban Çal. After the Turkish War of Independence, he returned to Constantinople and continued to write.[2][4]

Nazif, ever critical of the European imperialist powers, attracted once more their hostility when he wrote his satirical article "Hazret-i İsa'ya Açık Mektup" (Open Letter to Jesus) in which he described to Jesus all the crimes that were perpetrated by his followers in his name. Two weeks later he published "The Reply of Jesus" in which he, as if Jesus was talking, refuted the charges and replied that he is not responsible for the Christians' crimes. These two letters caused a furore among Christians in Turkey and Europe, putting Nazif on the verge of being put on trial. In the end this did not materialize, Nazif apologizing but being not less critical of the "Crusader mentality" of the imperialist Europeans, targeting Turkey in order to extend their power on its soil.[12])

He died of pneumonia on January 4, 1927, and was interred at the Edirnekapı Martyr's Cemetery.[4]

Bibliography

- Batarya ile Ateş (1917)

- Firak-ı Irak (1918)

- Çal Çoban Çal (1921)

- Tarihin Yılan Hikayesi (1922)

- Nasıruddin Şah ve Babiler (1923)

- Malta Geceleri (1924)

- Çalınmış Ülke (1924)

- Hazret-i İsa'ya Açık Mektup (1924)

- İki Dost (1925)

- İmana Tasallut-Şapka Meselesi (1925)

- Fuzuli (1926)

- Lübnan Kasrının Sahibesi (1926) (La châtelaine du liban, 1924 by Pierre Benoit), translation

See also

References

- ↑ Finkel, Caroline, Osman's Dream, (Basic Books, 2005), 57; "Istanbul was only adopted as the city's official name in 1930..".

- 1 2 3 Necati Alkan (November 2000). "Süleyman Nazif's Nasiruddin Shah ve Babiler: an Ottoman Source on Babi-Baha'i History. (With a Translation of Passages on Tahirih*)". Research Notes in Shaykhi, Babi and Baha'i Studies. h-net. 4 (2). Retrieved 2008-11-13.

- ↑ Henning, Barbara. Narratives of the History of the Ottoman-Kurdish Bedirhani Family in Imperial and Post-Imperial Contexts.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 "Süleyman Nazif Hakkında Bilgi" (in Turkish). Türkçe Bilgi-Ansiklopedi. Retrieved 2008-11-09.

- 1 2 Syed Tanvir Wasti (2014). "Süleyman Nazîf – A Multi-Faceted Personality". Middle Eastern Studies. 50 (3): 494. doi:10.1080/00263206.2014.886571.

- ↑ Dadrian, Vahakn N. (1991). "The Documentation of the World War I Armenian Massacres in the Proceedings of the Turkish Military Tribunal". International Journal of Middle East Studies. 23 (4): 550. doi:10.1017/S0020743800023412. ISSN 0020-7438. JSTOR 163884.

- 1 2 Gaunt, David (2006). Massacres, resistance, protectors: muslim-christian relations in Eastern Anatolia during world war I (1st Gorgias Press ed.). Piscataway, NJ: Gorgias. p. 306. ISBN 1-59333-301-3.

- 1 2 3 Üngör, Ugur Ümit (March 2012). The making of modern Turkey: nation and state in Eastern Anatolia, 1913–1950. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-965522-9.

- ↑ Anderson, Perry (2011). The new old world (pbk. ed.). London: Verso. p. 459. ISBN 978-1-84467-721-4.

Resit Bey, the butcher of Diyarbakir

- ↑ Verheij, Jelle (2012). Joost Jongerden, Jelle Verheij (ed.). Social relations in Ottoman Diyarbekir, 1870–1915. Leiden: Brill. p. 279. ISBN 978-90-04-22518-3.

- ↑ Gunal, Bulent (April 23, 2013). "Binlerce Ermeni'nin hayatını kurtarmıştı". HaberTurk (in Turkish).

Pasif de olsa bu olaya katılma, ailemizin şerefine dikkat et.

- ↑ Necati Alkan (November 2008). "Süleyman Nazif's 'Open Letter to Jesus': An Anti-Christian Polemic in the Early Turkish Republic". Middle Eastern Studies. h-net. 44 (6).