SS Shalom before her maiden voyage | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | |

| Ordered | 1959[2] |

| Builder | Chantiers de l'Atlantique, St Nazaire, France[1] |

| Cost | £7.5 million[2] |

| Yard number | Z21[1] |

| Launched | 10 November 1962[1] |

| Completed | 1964 |

| Acquired | February 1964[1] |

| Maiden voyage | 17 April 1964[1] |

| In service | 3 March 1964[2] |

| Out of service | 3 November 1995[1] |

| Identification | IMO number: 5321679[1] |

| Fate | Sunk outside Cape St. Francis, 26 July 2001[1] |

| General characteristics (as built)[1] | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 191.63 m (628 ft 8 in) |

| Beam | 24.81 m (81 ft 5 in) |

| Draught | 8.20 m (26 ft 11 in) |

| Decks | 10[2] |

| Installed power |

|

| Propulsion | Twin propellers[3] |

| Speed | 20 knots (37 km/h; 23 mph) |

| Capacity | 1,090 (72 first class, 1,018 tourist class)[3] |

| Crew |

|

| General characteristics (after 1964 refit)[2] | |

| Type | Ocean liner/cruise ship |

| Tonnage | 25,338 GRT[1] |

| Capacity | 1,012 (148 first class, 864 tourist class) |

| General characteristics (after 1973 refit)[2] | |

| Type | Cruise ship |

| Capacity | 725 passengers |

| General characteristics (after 1982 refit)[2] | |

| Type | Cruise ship |

| Capacity | 814 passengers |

SS Shalom was a combined ocean liner/cruise ship built in 1964 by Chantiers de l'Atlantique, St Nazaire, France, for ZIM Lines, Israel, for transatlantic service from Haifa to New York. In 1967, SS Shalom was sold to the German Atlantic Line, becoming their second SS Hanseatic. Subsequently she served as SS Doric for Home Lines, SS Royal Odyssey for Royal Cruise Line and SS Regent Sun for Regency Cruises. The ship was laid up in 1995 following the bankruptcy of Regency Cruises. Numerous attempts were made to bring her back to service, but none were successful. The ship sank outside Cape St. Francis, South Africa, on 26 July 2001, while en route to India to be scrapped.[1][2]

On 26 November 1964, SS Shalom accidentally rammed the Norwegian tanker Stolt Dagali outside New York, resulting in the loss of nineteen Stolt Dagali crew members and damage to the stern of the tanker.[1][2]

History

The government-controlled ZIM Lines had begun transatlantic operations from Haifa to New York in 1953 with SS Jerusalem. In 1959, they placed an order for a brand new ship for the transatlantic service with Chantiers de l'Atlantique, France.[2] Proposed names for the new ship included King David and King Solomon, but ZIM finally opted for Shalom (peace) as the name of their new flagship.[1] The project manager was Captain Rimon, and the technical superintendent was IDF Naval officer and architect Edmond Wilhelm Brillant.

Controversy erupted in the wake of a decision to install two kitchens, kosher and non-kosher – to appeal to a wider clientele. Despite a government committee deciding in favor of only one kitchen, the government left the choice to Zim Lines, who, despite facing strong religious opposition, stood by their choice. The Union of Orthodox Rabbis, Rabbinical Council of America, Conservative Rabbinical Assembly and other groups initiated grassroots campaigns to force the issue.[4][5]

Shalom was floated out of drydock on 10 November 1962, with only one kitchen. After fitting out, she commenced on her sea trials on 24 January 1964. In February of the same year she was delivered to ZIM Lines, arriving in Haifa for the first time on 3 March 1964.[1][2] A year after entry into service, the rabbinate agreed to let nonkosher food be served aboard cruises not visiting Israeli ports.[4]

After six months in service, Shalom was rebuilt at Wilton-Fijenoord, Rotterdam, Netherlands, with additional first-class cabins. The ship was also rebuilt in 1973 before entering service for Home Lines, and in 1982 before entering service for Royal Cruise Line.[1][2]

Service history

1964–1967: Zim Lines

The brand-new Shalom begun her career with a series of short cruises out of Haifa, before embarking on her fully booked first crossing to New York on 17 April 1964.[2] However, by the time she entered service the transatlantic liner trade was already in decline, with more passenger crossing the Atlantic by air than by sea since 1959.[6] To make her better suited for cruise service, Shalom was rebuilt in the Netherlands in October 1964, increasing the number of first-class cabins.[2]

Sometime after 2:00 on 26 November 1964, while 50 miles (80 km) outbound from New York with 616 passengers, bound for the Caribbean in thick fog, Shalom collided with the vegetable oil-carrying Norwegian tanker Stolt Dagali just outside Point Pleasant, New Jersey. Shalom's bow cut Stolt Dagali in half, killing nineteen of the tanker's forty-four crew. The tanker's bow section remained floating, but her aft section sank in 130 feet (39.62 m) of water within seconds. Shalom's chief radio officer issued an all-ships plea for help; the United States Coast Guard received the information at 2:25 am. Some 3½ hours later, the Coast Guard cutter Point Arden arrived at the scene, delayed for some time as the position provided had been 15 miles (24 km) off course.[7] Five of Stolt Dagali's seamen had been plucked from the sea by Shalom within 30 minutes of the collision and were treated in the ships hospital for shock. Point Arden picked up four crewmen, the rest being saved by helicopter.[7][8][9]

Shalom's bow was badly damaged, with a 40-foot gash over the waterline. Leaking into her number one hold, but afloat, she was able to slowly return to New York under her own power. Later, she was repaired by Newport News and Shipbuilding in Norfolk, Virginia.[2] During the inquiry that followed, her second mate testified that the ship's radar scope had been cluttered by noise and that work was being done to adjust it before the accident occurred. It also transpired that her lookout had been given permission for a coffee break just before the event, and was returning to the bridge when the collision happened.[8][9][10]

The inquiry concluded that both ships had been at fault, with a majority of the blame falling on Shalom for not posting proper lookout and admitting to a malfunctioning radar. A dive to the wreck of Stolt Dagali had shown her engine telegraph set to full speed, making her complicit in the accident.[9]

In 1965, barely a year after Shalom had been delivered, ZIM Lines made the decision to abandon transatlantic service, and their ships were sold off over the next two years.[11] Shalom stayed in ZIM service until November 1967, when she was sold to German Atlantic Line.[1] Built at a time of general decline of transatlantic travel with the introduction of the jet, coupled with a restricted and expensive kitchen aimed at a niche clientele on mainline voyages and being reliant on government subsidies during a time of Israeli economic decline, ZIM no longer saw an economic case for her.[5]

1967–1973: German Atlantic Line

The German Atlantic Line had been without a ship since the first TS Hanseatic had been destroyed by fire in New York in September 1966.[12] On 9 November 1967, Shalom was sold to the German Atlantic Line and renamed Hanseatic, becoming the second ship to bear that name. On 16 December 1967, the new Hanseatic set on a crossing from Cuxhaven, Germany, to New York, with only special invited guests on board. After that she was used for cruising around North America and Europe.[1][12] During 1968, she was also used on transatlantic service, but after that year, German Atlantic decided to abandon liner service and concentrate solely on cruising.[12]

1973–1981: Home Lines

In 1973, Hanseatic was again sold as a replacement for a ship lost in a fire, this time for Home Lines' Homeric.[13] Home Lines and German Atlantic Line were both led by Nicolaos Vernicos Eugenides, who made the transfer of Hanseatic to the former's fleet a straightforward affair.[12] After being sold to Home Lines on 25 September 1973, Hanseatic was renamed Doric and subsequently rebuilt with a larger after superstructure. Home Lines used her for cruising from Port Everglades to the West Indies during the northern hemisphere winter season, and New York to Bermuda during the summer season.[1][2]

In preparation for the delivery of the new Atlantic in 1982,[14] Home Lines sold Doric to Royal Cruise Line in 1981.[1][2]

1981–1988: Royal Cruise Line

Under her new owners Doric was renamed Royal Odyssey. Before entering service for Royal Cruise Line, she received a four-month refit at the Greek shipyards of Perama and Neorion, where her funnel was rebuilt, her topmost deck expanded and a bulbous bow added below the waterline.[1][2] Royal Odyssey entered service for Royal Cruise Line on 25 May 1982,[1] and was used for cruises all around the world, including occasional cruises around the Pacific from Australia.[2][3][15]

In June 1988, Royal Cruise Line took delivery of the new MS Crown Odyssey.[16] The company operated with a three-ship fleet until November of the same year, when Royal Odyssey was sold to Regency Cruises.[11]

1988–1995: Regency Cruises

Royal Odyssey was renamed Regent Sun by Regency Cruises, and entered service for them on 9 December 1988. She continued sailing for Regency until 3 November 1995, when she was arrested at Jamaica, due to the poor financial situation of her owners. Subsequently, Regent Sun and all other Regency ships were laid up and put for sale.[1][2]

1995–2001: laid up

Following the collapse of Regency Cruises, Regent Sun never returned to active service, despite the interest expressed by several companies in operating her. In October 1996, Royal Venture Cruises wished to charter her under the name Sun Venture for additional cruise service,[1][2][11] while in 1997, Premier Cruises expressed interest in purchasing the ship, but withdrew their offer due to her poor condition. In 1998, the ship was first sold to Tony Travel & Agency and renamed Sun, then sometime later to International Shipping Partners and renamed Sun 11, but despite these changes in ownership, she remained laid up in the Bahamas. In 2000, International Shipping Partners begun rebuilding Sun 11 into a hotel ship, with a planned new name as Canyon Ranch at Sea, but this plan too fell through, and in 2001 Sun 11 was sold to Indian shipbreakers. While en route to India under tow, Sun 11 started taking in water on 25 July 2001 while outside South African territorial waters. The South African authorities forbade the ship to enter South African waters, and on 26 July she sank off Cape St. Francis.[1]

Design

Exterior design

Shalom was designed according to the principles of the era, with engines placed two-thirds aft and two slim funnels placed side-by side instead of the large traditional funnels. The funnel design in particular resembled SS Rotterdam of Holland America Line and SS Canberra of P&O, both of which were still under construction at the time Shalom was being designed. Her hull and superstructure design were optimized for transatlantic traffic, with the promenade decks entirely glass-enclosed.[2]

In original livery Shalom was almost entirely white, with an all-white hull and superstructure and white funnels with only small black bands around them, with the ZIM Lines logo between them. Originally her name and homeport were written on her hull in both Latin and Hebrew alphabet. When she entered service for German Atlantic Line, the name Hanseatic was written with large letters on her bow, arguably unbalancing her profile. In Home Lines service she received yellow funnels and a yellow radar mast, with the name written in the bow in somewhat smaller typeface.[2]

The 1982 refit radically altered the ship's profile, when the original slim funnels were replaced with a single large Queen Elizabeth 2-esque funnel, and the outer decks between the bridge and the funnel were built in. Additionally, a bulbous bow was added below the waterline, improving the ship's sea-keeping abilities. During the refit, the ship's livery was also altered, with the new funnel painted in blue and white, while a white decorative ribbon was added to her hull. The exact same livery was maintained as Regent Sun, with the Regency Cruises funnel symbol replacing that of Royal Cruise Line.[2]

Interior design

The public spaces on board Shalom were spread over two decks, originally named Rainbow and Olive Branch, which were the sixth- and seventh-highest passenger-accessible decks respectively. Facilities included a cinema, winter garden, tavern, shopping center, night club, and separate lounges for first- and tourist-class passengers. Shalom's award-winning interiors were mostly designed by Dora Gad in a bright, contemporary style.[2]

Gallery

1963 Israel stamp commemorating Shalom's launch

1963 Israel stamp commemorating Shalom's launch Brillant (left) and Amlan (right) in shipyards design room, Chantiers de l'Atlantique

Brillant (left) and Amlan (right) in shipyards design room, Chantiers de l'Atlantique Dry dock picture bow 1963

Dry dock picture bow 1963 Dry dock picture bow and upper decks accommodations 1963

Dry dock picture bow and upper decks accommodations 1963 Shalom after flotation, red primer color on accommodations, shifted from shipyards to special dedication with Paula Ben-Gurion, wife of David Ben Gurion, prime minister of Israel

Shalom after flotation, red primer color on accommodations, shifted from shipyards to special dedication with Paula Ben-Gurion, wife of David Ben Gurion, prime minister of Israel Stage of ceremony near the ship's bow

Stage of ceremony near the ship's bow Wives of ZIM mission engineers approaching

Wives of ZIM mission engineers approaching Paula Ben-Gurion in white suit

Paula Ben-Gurion in white suit Invitation to commissioning cocktail party, March 1964

Invitation to commissioning cocktail party, March 1964 Cocktail party menu, March 1964

Cocktail party menu, March 1964 Edmond W. Brillant, head of the table with glasses

Edmond W. Brillant, head of the table with glasses Edmond W. Brillant, dark suit with glasses

Edmond W. Brillant, dark suit with glasses Ship in service after commissioning, view from stern to bow

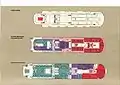

Ship in service after commissioning, view from stern to bow Ship's deck plan page 1

Ship's deck plan page 1 Ship's deck plan page 2

Ship's deck plan page 2 Ship's deck plan page 3

Ship's deck plan page 3 Ship's deck plan page 4

Ship's deck plan page 4 SS Shalom as SS Hansetic in Hamburg, 1969

SS Shalom as SS Hansetic in Hamburg, 1969 Hanseatic in Hamburg, June 1973

Hanseatic in Hamburg, June 1973_(Kiel_57.375).jpg.webp) Doric in Kiel

Doric in Kiel

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 27 28 Asklander, Micke. "T/S Shalom (1964)". Fakta om Fartyg (in Swedish). Archived from the original on 10 January 2012.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 25 26 Goossens, Renben. "Israel's Flagship – SS Shalom". Zim Israel Navigation Co. SS Maritime. Retrieved 16 February 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 Miller, William H. Jr. (1995). The Pictorial Encycpedia of Ocean Liners, 1860–1994. Mineola: Dover Publications. pp. 118. ISBN 0-486-28137-X.

- 1 2 Liebman, Charles S. (1977). Pressure Without Sanctions: The Influence of World Jewry on Israeli Policy. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. ISBN 978-0-8386-1791-5.

- 1 2 Birnbaum, Ervin (1970). The Politics of Compromise: State and Religion in Israel. Fairleigh Dickinson University Press. p. 257. ISBN 978-0-8386-7567-0.

- ↑ Ward, Douglas (2006). The Complete Guide to Cruising and Cruise Ships. Singapore: Berlitz. pp. 23. ISBN 981-246-739-4.

- 1 2 "Disasters: Left To Be Answered". Time Magazine. 4 December 1964. Archived from the original on July 15, 2010. (subscription required)

- 1 2 Time Magazine 57 (23). ISSN 0024-3019.

- 1 2 3 Bonner, Kit. "Death of the tanker Stolt Dagali". Retrieved 22 April 2011.

- ↑ Donahue, James L. "Tanker Stolt Dagali Wrecked In Atlantic Collision". Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 Boyle, Ian. "Shalom". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- 1 2 3 4 Boyle, Ian. "Hamburg Atlantik Line". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Boyle, Ian. "Home Lines". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Asklander, Micke. "M/S Atlantic (1982)" (in Swedish). Fakta om Fartyg. Archived from the original on 28 March 2012.

- ↑ Boyle, Ian. "Royal Cruise Line". Simplon Postcards. Retrieved 10 May 2013.

- ↑ Asklander, Micke. "M/S Crown Odyssey (1988)" (in Swedish). Fakta om Fartyg. Archived from the original on 11 January 2012.