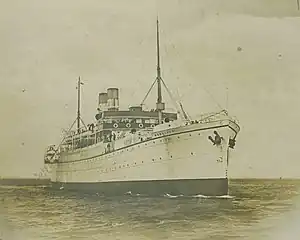

The ship as Moraitis | |

| History | |

|---|---|

| Name |

|

| Namesake |

|

| Owner |

|

| Operator |

|

| Port of registry | |

| Builder | John Priestman & Co, Sunderland |

| Yard number | 120 |

| Launched | 16 April 1907 |

| Completed | June 1907 |

| Commissioned | as troop ship, November 1912 |

| Decommissioned | as troop ship, July 1913 |

| Maiden voyage | 1 July 1907 |

| Identification |

|

| Fate | Scrapped in 1933 |

| General characteristics | |

| Type | Ocean liner |

| Tonnage | |

| Length | 400.0 ft (121.9 m) |

| Beam | 50.0 ft (15.2 m) |

| Depth | 27.6 ft (8.4 m) |

| Decks | 1 |

| Installed power | 574 NHP |

| Propulsion |

|

| Speed | 13 knots (24 km/h) |

| Capacity |

|

SS Themistocles was a Greek passenger steamship that was built in England in 1907 as Moraitis, renamed Themistocles in 1908, and scrapped in Italy in 1933. She was built to be a transatlantic ocean liner, but she served also as a troop ship.

Building

In 1907 DG Moraitis, the Greek owner of a fleet of cargo ships, founded the Hellenic Transatlantic Line.[1] He ordered Moraitis from John Priestman and company of Southwick, Sunderland, who launched her on 16 April 1907 and completed her that June.[2] Her registered length was 400.0 ft (121.9 m), her beam was 50.0 ft (15.2 m) and her depth was 27.6 ft (8.4 m). As built, her tonnages were 5,784 GRT and 3,764 NRT.[3] She had berths for 100 passengers in First Class and 1,500 in Third Class.[4]

Moraitis had twin screws. Each screw was driven by a three-cylinder triple expansion steam engine, built by George Clark, Ltd of Sunderland. The combined power of her twin engines was rated at 574 NHP[5] and gave her a speed of 13 knots (24 km/h).[4]

Moraitis registered Moraitis on the Aegean island of Andros.

Early career

On 1 July 1907 Moraitis began her maiden voyage, which was from Piraeus to New York via Patras, Gibraltar and Bermuda. On 5 September 1908 she sailed from Smyrna to New York via Piraeus, Patras and Algiers.[4] This turned out to be her last voyage with Hellenic Transatlantic Line, as the company then went bankrupt.

A new Hellenic Transatlantic Steam Navigation Company was formed to take over Hellenic Transatlantic Line's ships and services.[6] Moraitis' new owner renamed her Themistocles, after the ancient Athenian politician and general Themistocles, and re-registered her in Piraeus.[5]

On 12 November 1908 Themistocles started her first voyage for her new owner, sailing from Smyrna to New York via Piraeus, Kalamata and Patras.[4] In May 1909 a new Hellenic Transatlantic ship, Athinai, joined Themistocles on the same route.[7] By 1909 Themistocles's tonnages had been revised to 6,045 GRT and 3,924 NRT.[5]

Immigration cases

In 1910 the US Bureau of Immigration started investigating the Hellenic Transatlantic Company on suspicion of breaking the Immigration Act of 1907. The Bureau placed the company's ships under covert surveillance. It concluded that on each voyage to New York, each of it ships brought three or four dozen immigrants who avoided the immigration procedures on Ellis Island by either posing as members of the crew or being concealed aboard by members of the crew.[8]

On 18 December 1910 the Bureau searched Themistocles in New York. She was due to leave on 20 December, but she was detained to be searched a second time. The New York Times reported that "Locked in one small room [detectives] found four youths, the oldest about 20 years, who had been brought here neither as members of the crew nor as passengers. The men were arrested. An examination on board brought out the fact that the men had paid an average of $40 each to be brought here. They accused two of the officers in the Themistocles of being in on the plot." The four young men were taken to Ellis Island.[9]

The Immigration Bureau asked Themistocles' Master, Captain Spiridion Paramythioti, to surrender his two officers for arrest. He refused, and warned that as the Bureau did not have a Federal warrant, any attempt to arrest the pair aboard the ship would violate Greek law. However, the Bureau did deport about 40 people on the ship when she left New York. The Immigration authorities considered asking the Federal government to revoke the Hellenic Transatlantic Company's charter, and for the US Congress to change US law to give immigration officers more powers over foreign ships.[9]

When Themistocles docked in New York on 18 December, her passengers included a retired Hellenic Army Colonel, Nikolas Simopoulos, who was travelling under a false name. He was suspected of the defalcation of $4 million from Greek government funds. The Greek Ambassador in Washington alerted the Greek Consul in New York, who had a wireless telegraph message transmitted to Themistocles telling Captain Paramythioti about Simopoulos before his ship reached port.[10]

When Themistocles docked, the Greek Consul went aboard and arrested Simopoulos. US immigration authorities wanted to take Simopoulos to Ellis Island, but Paramythioti refused to surrender him, and insisted Simopoulos stay aboard to be repatriated to face trial.[10] On 19 December a US immigration board of inquiry met aboard Themistocles to consider whether Simopoulos should be deported. Simopoulos insisted he would return to Greece to try to clear his name.[11] On 20 December the board of inquiry ordered that Simopoulos be deported.[12]

In January 1911, US immigration authorities in New York sought to muster and examine Themistocles' crew. Her Master at first refused, but eventually co-operated under protest.[13]

On 25 February 1911 the Hellenic Transatlantic Company's New York agent and his secretary were arrested, Athinai was searched, and 22 of her officers and crew were arrested, including her Master.[8] The Bureau of Immigration wanted to interview Captain Paramythioti, as well. But the next time Themistocles docked in New York, she had a different Master and set of officers, except for her purser.[14]

Later career

By 1911 Themistocles' code letters were HRVK, and she was equipped for wireless telegraphy.[15] The Marconi Company supplied and operated her wireless equipment under contract.[16] By 1914 her call sign was SVT. Her wireless set had a transmission range of 220 nautical miles (410 km).[17]

On 8 October 1912 the First Balkan War began. The Greek government chartered Themistocles, Athinai, the National Steam Navigation Company liner Macedonia and another Greek ship to take to Greece 6,400 Greeks living in the USA who were either Hellenic Army reservists or volunteers. Themistocles was due to leave New York on 17 October.[18] She carried 1,200 military volunteers.[19] That November the Royal Hellenic Navy requisitioned her as a troop ship. She was returned to her owners in July 1913.[4]

In August 1914 the Hellenic Transatlantic company went bankrupt. The National Steamship Navigation Company Ltd of Greece bought Themistocles,[20] re-registered her in Andros, kept her on the same route, and appointed Embiricos Brothers to manage her.[21]

In August 1920 US Customs officers raided Themistocles in New York. Under a trap door in her engine room they found $80,000 worth of cocaine, morphine and opium, and 30 cases of whisky.[22]

In February 1921 the United States Public Health Service imposed 12 days' quarantine on incoming ships to prevent typhus cases from entering the country. On 12 February Themistocles and two other liners were detained at the quarantine station on Hoffman Island in Lower New York Bay. All her Third Class passengers were taken ashore, and their clothes and baggage fumigated.[23] All 500 of her passengers passed medical inspection, and she disembarked them in New York on 21 February.[24]

On 31 October 1921 Themistocles left Piraeus on one of her regular sailings to New York. Her crew found three stowaways in one of her holds, and detained them to be disembarked at Patras. One evaded his guards, remained aboard, and reappeared when the ship was in mid-Atlantic. He was put to work in the galley, and when the ship was approaching New York he was locked in a cabin to be surrendered to US immigration officers. But the stowaway escaped from the cabin and was not recaptured.[25]

In December 1921 Abraham Krotoshinsky, a survivor of The Lost Battalion on the Western Front, sailed from New York on Themistocles on his way to Palestine.[26]

On 31 August 1922 Themistocles left Smyrna, a fortnight before Turkish forces burned the city. She called at Piraeus, where $5 million in gold from the National Bank of Greece was embarked in her strong room. On 27 September she reached New York, where the gold was to be delivered to the Federal Reserve Bank of New York.[27]

On 6 January 1924 Themistocles left Patras on a scheduled voyage to New York. On 20 January a storm off the Azores disabled her wireless aerial. 36 hours later, volunteers with lifelines went aloft and repaired it. On the afternoon of 21 January the headwind was so great that she made only 3 nautical miles (6 km) in three hours. She reached New York on 2 February, seven days late.[28]

On 28 August 1924 Themistocles left Piraeus on the last of her regular voyages via Kalamata and Patras to New York. In 1927 she made one more voyage to New York, which left Piraeus on 14 September.[4] Also in 1927, Themistocles' tonnages were revised to 5,956 GRT and 3,892 NRT.[29]

Themistocles was scrapped in Savona in northern Italy in 1933.[2][30]

References

- ↑ Swiggum, Susan; Kohli, Marjorie (6 February 2005). "Hellenic Transatlantic Line". TheShipsList. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Moraitis". Wear Built Ships. Shipping and Shipbuilding Research Trust. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ↑ LLoyd's Register, 1907.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Swiggum, Susan; Kohli, Marjorie (25 September 2008). "Ship Descriptions – M". TheShipsList. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- 1 2 3 LLoyd's Register, 1909.

- ↑ Swiggum, Susan; Kohli, Marjorie (6 February 2005). "Hellenic Transatlantic Steam Navigation Co". TheShipsList. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ↑ Swiggum, Susan; Kohli, Marjorie (1 July 2012). "Ship Descriptions – A". TheShipsList. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- 1 2 "Raid Greek liner, arrest 27 of crew". The New York Times. 26 February 1911. p. 4. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- 1 2 "May discipline Greek line". The New York Times. 22 December 1910. p. 4. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- 1 2 "$4,000,000 defaulter on liner, they say". The New York Times. 19 December 1910. p. 1. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Not a defaulter, says Simopoulos". The New York Times. 20 December 1910. p. 8. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Lone wish of the deported". The New York Times. 21 December 1910. p. 4. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Unearth plot to smuggle aliens". The New York Times. 6 January 1911. p. 7. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Indicted officers quit their ship". The New York Times. 18 April 1911. p. 7. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ LLoyd's Register, 1911.

- ↑ LLoyd's Register, 1914.

- ↑ The Marconi Press Agency Ltd 1914, p. 412.

- ↑ "Greeks rushing for home". The New York Times. 5 October 1912. p. 4. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "For the Last Fortnight Outgoing Steamers Have Not Been Big Enough to Carry All Who Want to Take Up Arms for Their Native Land". The New York Times. 20 October 1912. p. 57. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ Swiggum, Susan; Kohli, Marjorie (5 February 2005). "National Greek Line / Byron S.S. Co". TheShipsList. Retrieved 9 June 2022.

- ↑ LLoyd's Register, 1915.

- ↑ "75 fined $100 each in dry law cases". The New York Times. 26 August 1920. p. 17. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "3 liners held back by quarantine jam". The New York Times. 22 February 1921. p. 17. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Treasury decries immigration ban". The New York Times. 23 February 1921. p. 7. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Elusive stowaway hides fourth time". The New York Times. 25 November 1921. p. 26. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Nathan Straus sends war hero abroad". The New York Times. 3 December 1921. p. 26. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Greek liner brings $5,000,000 in Francs". The New York Times. 28 September 1922. p. 2. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ "Ship battered by storm". The New York Times. 3 February 1924. p. 9. Retrieved 9 June 2022 – via Times Machine.

- ↑ LLoyd's Register, 1927.

- ↑ LLoyd's Register, 1934.

Bibliography

- Bonsor, NRP (1979). North Atlantic Seaway. Vol. 3. Jersey: Brookside Publications. p. 1,371. ISBN 978-0905824024.

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1907. Supplement: M – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1909. Supplement: T – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of British and Foreign Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1911. THE – via Internet Archive.

- "List of Vessels Fitted With Installation of Wireless Telegraphy". Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers, Sailing Vessels, and Owners. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1914.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1915. THE – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1927. THE – via Internet Archive.

- Lloyd's Register of Shipping. Vol. I–Steamers. London: Lloyd's Register of Shipping. 1934. THE – via Internet Archive.

- The Marconi Press Agency Ltd (1914). The Year Book of Wireless Telegraphy and Telephony. London: The Marconi Press Agency Ltd.