| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

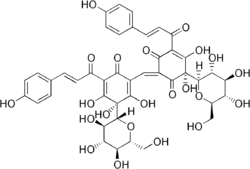

| IUPAC name

(2Z,6S)-6-β-D-Glucopyranosyl-2-[ [(3S)-3-β-D-glucopyranosyl-2,3,4-trihydroxy-5-[(2E)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-oxo-2-propenyl]-6-oxo-1,4-cyclohexadien-1-yl]methylene]-5,6-dihydroxy-4-[(2E)-3-(4-hydroxyphenyl)-1-oxo-2-propenyl]-4-cyclohexene-1,3-dione | |

Other names

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol) |

|

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.048.150 |

PubChem CID |

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA) |

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C43H42O22 | |

| Molar mass | 910.787 g·mol−1 |

| Appearance | Red powder |

| Slightly soluble | |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

Infobox references | |

Carthamin is a natural red pigment derived from safflower (Carthamus tinctorius), earlier known as carthamine.[2] It is used as a dye and a food coloring. As a food additive, it is known as Natural Red 26.

Safflower has been cultivated since ancient times, and carthamin was used as a dye in ancient Egypt.[2] It was used extensively in the past for dyeing wool for the carpet industry in European countries, and in the dyeing of silk and the creation of cosmetics in Japan, where the color is called beni (紅);[3][4] however, due to the expensive nature of the dye, Japanese safflower dyestuffs were sometimes diluted with other dyes, such as turmeric and sappan.[5]: 1 It competed with the early synthetic dye fuchsine as a silk dye after fuchsine's 1859 discovery.[6]

Carthamin is composed of two chalconoids; the conjugated bonds being the cause of the red color. It is derived from precarthamin by a decarboxylase.[7] It should not be confused with carthamidin, another flavonoid.

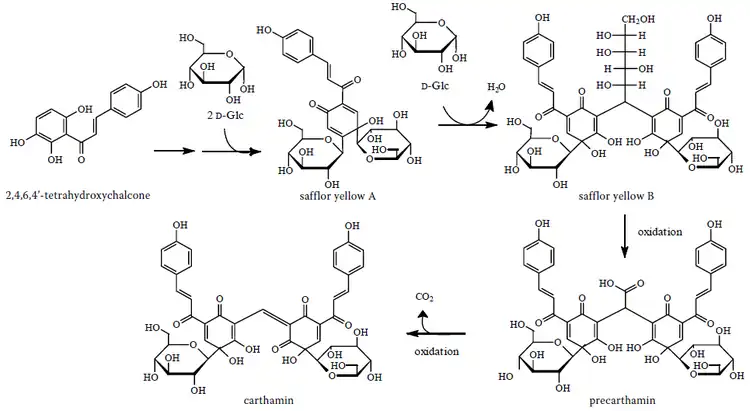

The carthamin is biosynthesized from a chalcone (2,4,6,4'-tetrahydroxychalcone) and two glucose molecules to give safflor yellow A and with other glucose molecule, safflor yellow B. The next step is the formation of precarthamin and finally carthamin.[8]

References

- ↑ Merck Index, 11th Edition, 1876

- 1 2 De Candolle, Alphonse. (1885.) Origin of cultivated plants. D. Appleton & Co.: New York, p. 164. Retrieved on 2007-09-25.

- ↑ Vankar, Padma S.; Tiwari, Vandana; Shanker, Rakhi; Shivani (2004). "Carthamus tinctorius (Safflower), a commercially viable dye for textiles". Asian Dyer. 1 (4): 25–27.

- ↑ Morse, Anne Nishimura, et al. MFA Highlights: Arts of Japan. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts Publications, 2008. p161.

- ↑ Arai, Masanao; Iwamoto Wada, Yoshiko (2010). "BENI ITAJIME: CARVED BOARD CLAMP RESIST DYEING IN RED" (PDF). Textile Society of America Symposium Proceedings. University of Nebraska - Lincoln. Archived from the original on 2 November 2021.

- ↑ Chevreul, M. E. (July 1860). "Note sur les étoffes de soie teintes avec la fuchsine, et réflexions sur le commerce des étoffes de couleur." Répertoire de Pharmacie, tome XVII, p. 62. Retrieved on 2007-09-25.

- ↑ Cho, Man-Ho; Paik, Young-Sook; Hahn, Tae-Ryong (2000). "Enzymatic Conversion of Precarthamin to Carthamin by a Purified Enzyme from the Yellow Petals of Safflower". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 48 (9): 3917–21. doi:10.1021/jf9911038. PMID 10995291.

- ↑ Man-Ho Cho; Young-Sook Paik; Tae-Ryong Hahn (2000). "Enzymatic Conversion of Precarthamin to Carthamin by a Purified Enzyme from the Yellow Petals of Safflower". J. Agric. Food Chem. 48 (9): 3917–3921. doi:10.1021/jf9911038. PMID 10995291.