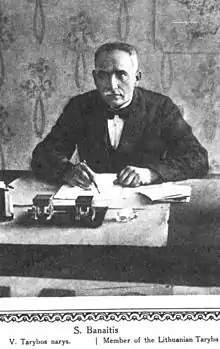

Saliamonas Banaitis | |

|---|---|

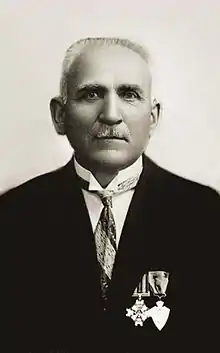

Portrait of Banaitis in 1928 | |

| Born | 15 July 1866 Vaitiekupiai, Augustów Governorate, Congress Poland |

| Died | 4 May 1933 (aged 66) |

| Resting place | Petrašiūnai Cemetery |

| Nationality | Lithuanian |

| Occupation(s) | Farmer, publisher, banker |

| Known for | Signatory of the Act of Independence of Lithuania |

| Political party | Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party Economic and Political Union of Lithuanian Farmers |

| Children | 4 sons (including Kazimieras Viktoras) and 1 daughter |

| Relatives | Brother-in-law priest Justinas Pranaitis |

| Awards | Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas |

Saliamonas Banaitis (ⓘ; 15 July 1866 – 4 May 1933) was a Lithuanian printer, politician, and businessman. He was one of the twenty signatories of the Act of Independence of Lithuania in 1918.

Early death of his father and brother forced Banaitis to quit school in order to work at his family's farm. Despite lack of higher education, he joined Lithuanian cultural life – smuggled banned Lithuanian press, assisted Vincas Kudirka with the publication of Lithuanian-language newspapers Varpas and Ūkininkas, participated in the Great Seimas of Vilnius. In 1905, he moved to Kaunas and established the first Lithuanian printing press in the city. In close cooperation with the Society of Saint Casimir, his press published almost 400 books and ten periodicals. He founded a credit union in 1911.

Banaitis was particularly active during World War I. He established the first Lithuanian gymnasium as well as 12 primary schools in Kaunas, organized an ensemble of kanklės players, prepared and published a political proposal for a future Lithuanian state along the historical traditions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania. In 1917, he attended Vilnius Conference and was elected to the 20-member Council of Lithuania. On 16 February 1918, he was the second (after Jonas Basanavičius) to sign the Act of Independence of Lithuania. At the outbreak of the Lithuanian Wars of Independence, he recruited men to join the newly formed Lithuanian Army.

In independent Lithuania, Banaitis was one of the founders of the right-wing Economic and Political Union of Lithuanian Farmers and editor of its newspaper Žemdirbių balsas (Voice of Farmers). The union failed to win seats in the parliamentary elections and merged with the Party of National Progress to form the Lithuanian Nationalist Union in 1924. In 1918, Banaitis was one of the founders and council member of the Trade and Industry Bank. Due to mismanagement, the bank went bankrupt in 1927. He was also co-founder and vice-chairman of the Lithuanian Steamship Corporation. His last project, the construction of the Kaunas bus station, was completed already after his death.

Early life and education

Banaitis was born in Vaitiekupiai, Šakiai District, Augustów Governorate, Congress Poland. On his mother's side, his ancestors had French roots and lived in East Prussia until 1830.[1] His mother participated in the Uprising of 1863. His father was a Lithuanian farmer; he died when Banaitis was three years old. He attended a primary school in Sintautai for three years. In 1879, he enrolled into the Marijampolė Gymnasium.[1] His classmate was Kazys Grinius, future President of Lithuania.[2] His tutor for the gymnasium entrance examinations was priest Antanas Radušis who introduced Banaitis to the banned Lithuanian press.[3] In 1883, Banaitis was forced to quit school when his brother died and his mother needed help at the 71-hectare (180-acre) farm.[4] Banaitis never finished his education and was the only of the twenty signatories without tertiary education.[5]

Despite the circumstances, Banaitis did not limit himself to farming. He began smuggling Lithuanian books that were banned by the Tsarist authorities and successfully evaded the police. Together with a partner, who had returned from United States, he established shops in Sintautai, Griškabūdis, Lukšiai.[6] In 1886, he got acquainted with Martynas Jankus and joined the cultural Birutė Society. At least four Lithuanians got a job at Jankus' press with Banaitis' recommendations.[7] His farm became known as a center of Lithuanian culture. Vincas Kudirka visited it in summer 1888 and Juozas Adomaitis-Šernas lived there in spring 1889 hiding from the German police.[7] In 1890, when Kudirka became ill, Banaitis wanted to take over the publication of the monthly Lithuanian-language newspapers Varpas and Ūkininkas, but due to disagreements between Kudirka and Jankus, the newspapers were left in the care of doctor Juozas Bagdonas.[8]

In 1890, Banaitis married Marijona,[9] sister of priest Justinas Pranaitis and organist Petras Juozas Pranaitis. They had five children, one daughter and four sons. Son Kazimieras Viktoras Banaitis (1896–1963) studied at the Leipzig Conservatory and became a known composer. Son Bronius (1898–1967) studied at the Technische Universität Darmstadt and became an engineer. Son Vytautas (1900–1980), educated at the Wharton School of the University of Pennsylvania, was the only member of the family to remain in Lithuania after the Soviet occupation of Lithuania in 1940.[10]

In 1900–1902, Banaitis attended bookkeeping courses in Saint Petersburg. After the graduation, he was offered a government job in the Vyatka Governorate, but refused.[11] Upon return to Lithuania, he spent two years trying to establish a modern dairy. He bought equipment in Warsaw from Jonas Smilgevičius and attempted to produce butter and cheese, but other farmers did not support the effort and the enterprise failed.[12] He attended the Great Seimas of Vilnius in December 1905, but was not very active in its proceedings.[12]

Owner of a printing press

When the Lithuanian press ban was lifted, he petitioned the Ministry of National Education for a permit to open a Lithuanian press in Kaunas. The permit was received but the authorities demanded to print pro-Russian newspaper Lietuvos balsas (Voice of Lithuania).[13] The first issue was published on 19 January 1906, but perhaps due to sabotage by Banaitis,[14] the newspaper was discontinued after 32 issues.[15] The beginnings were difficult – there was a lack of equipment (the first acquisition was a hand-powered Koenig & Bauer press) and of qualified personnel. To obtain enough funds, Banaitis mortgaged his farm in Vaitiekupiai. By 1914, the press grew to 30 employees and four printing presses.[14] But due to lack of quality equipment and typeset, the publications were of low polygraphic quality.[16]

Banaitis press closely cooperated with the Society of Saint Casimir. The major project was the publication of the full Bible translation into Lithuanian by Juozapas Skvireckas from the Vulgate. The first sections of the New Testament (the four gospels and Acts of the Apostles) were published already in 1906. In total, six volumes were published in 1911–1937 – the first two volumes were published under Banaitis' ownership.[17] In 1907, he published his own translation of seven Japanese fairy tales from Russian to address the public interest in Japan in the wake of the Russo-Japanese War.[18] In ten years, the press published about 300 books with a combined circulation of 1.3 million. Some of these were small cheap booklets printed in thousands of copies, such as a 13-page booklet on good confession (50,000 copies sold for three kopeykas each) in 1905[19][20] and a farmer's calendar (75,000 copies sold for three kopeykas each) in 1910.[14] In total, between 1905 and 1918, the press published 358 Lithuanian, 34 Russian, five Polish, and one Latin book.[14] The press also printed Lithuanian newspapers Garnys, Viensėdis and magazines Ateitis, Bažnytinė apžvalga, Draugija, Lietuvaitė, Lietuvos mokykla, Nedėldienio skaitymas, Vienybė.[21]

During World War I, Banaitis did not evacuate to Russia and continued to work in Kaunas. When Germans captured Kaunas in summer 1915, Banaitis published newspaper Kauno žinios (Kaunas News). It was a brief newsletter-type publication on the developments in the front and in the city.[22] Banaitis wanted to publish it only in Lithuanian, but Ober Ost officials insisted on translating it to German and Polish. The newspaper was discontinued by the end of 1915. Banaitis wanted to publish other Lithuanian periodicals, but did not get a permit from the German authorities.[22] Banaitis then secretly printed an anti-German proclamation. When it was discovered by the Germans, two employees were arrested and imprisoned. Banaitis managed to secure their release in two months.[23] On 1 November 1918, Banaitis sold his press for 25,000 Rbls to the Society of Saint Casimir.[24]

During World War I

Cultural and educational activities

Back in 1904, Banaitis joined the Daina Society which organized music and theater performances.[8] In 1915, Banaitis organized Kaunas chapter of the Lithuanian Society for the Relief of War Sufferers and became its vice-chairman.[25] In early September 1915, Banaitis managed to obtain a permit for a Lithuanian gymnasium (present-day Aušra Gymnasium).[26] With financial help from the Lithuanian Society and resources of the educational Saulė Society, Banaitis organized the new school – located the premises, obtained supplies, and recruited students and teachers.[27] The school opened by the end of 1915 with about 60 students.[28] Banaitis' son Bronius was among its students and graduated in spring 1919 while another son Kazimieras Viktoras was one of the first teachers.[29] Saulė Society soon took over the school administration. Banaitis further established 12 elementary schools and was their inspector.[30] In late 1915, he also organized bookkeeping courses. He and four others taught 20 students for four months.[31]

In winter 1915, the press was mostly idle as few orders came due to war. Banaitis decided to hire Pranas Puskunigis, a known kanklės player from Skriaudžiai, to establish and lead a kanklės ensemble from his press workers.[32] The ensemble began giving performances in late 1915. Accompanied by a student choir from the Saulė Gymnasium (led by Banaitis' son and future composer Kazimieras Viktoras), the ensemble organized a concert at the Kaunas City Theater on 5 January 1916.[33] The ensemble was also invited to perform in Königsberg. When the society of kanklės players was organized in 1925, both Puskunigis and Banaitis were among the co-founders.[25]

Political activities

On 15 December 1915, 800 copies of a proclamation authored by Banaitis, Jonas Kriaučiūnas, Adomas Jakštas, and others was printed at the Banaitis press.[34] It was a proposal for a constitution of a future Lithuanian state. The proclamation envisioned a Lithuanian–Belarusian–Latvian confederation along the historical traditions of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania ruled by a Grand Duke and two-chamber parliament. The project guaranteed democratic freedoms and human rights, such as universal voting rights, freedom of religion, freedom of speech, freedom of the press, and freedom of association.[34] However, it did not attract greater interest.[35]

In September 1917, as a member of the Lithuanian Christian Democratic Party, Banaitis attended Vilnius Conference and was elected to the 20-member Council of Lithuania. Since he was based in Kaunas and the council was based in Vilnius, he was not among the most active or influential members of the council.[36] On 15 January 1918, Banaitis was appointed to a three-member commission to initiate the creation of Lithuanian police and military, but the German administration would not allow it.[37] When the council debated whether Lithuania should be a constitutional monarchy or a democratic republic, Banaitis supported monarchy. On 16 February 1918, he was the second (after Jonas Basanavičius) to sign the Act of Independence of Lithuania.[36] When Germany signed the Armistice of 11 November 1918 and Soviet Russia began its westward offensive starting the Lithuanian–Soviet War, Banaitis was active in organizing the Lithuanian Army. His goal was to recruit 2,000 volunteers in Kaunas.[38] For a few months in 1919, he served as a governor of Šakiai district. During that time he organized local administration and recruited 120 men for the Lithuanian Army. His four sons also became army volunteers.[38]

Post-independence

Political and editorial activities

Banaitis founded and became vice-chairman of the Economic and Political Union of Lithuanian Farmers (Lithuanian: Ekonominė bei politinė Lietuvos žemdirbių sąjunga). Its founding meeting took place on 28 April 1919.[39] It was a right-wing political party that sympathized and eventually merged with the Party of National Progress to form the Lithuanian Nationalist Union.[40] In May 1919, it briefly discussed a possible merger with the Farmers' Association.[41] In October 1919, Banaitis began editing and publishing party's newspaper Žemdirbių balsas (Voice of Farmers).[42] In his native Vaitiekupiai and nearby Sintautai, he established a milk separating and grain cleaning points.[8]

Banaitis, as a candidate of the union, participated in the April 1920 elections to the Constituent Assembly of Lithuania, but the union failed to win any seats.[43] Due to the poor election results, the publication of Žemdirbių balsas ceased between May 1920 and January 1921, and between February 1921 and January 1922.[44] When the publication resumed, Banaitis used the newspaper to advocate against monopoly (particularly for linen production), explain benefits of property insurance, promote the idea of a Farmer's Bank, and agitate against the ruling parties.[45] After the Union of Lithuanian Farmers failed to win any seats in the October 1922 elections, the newspaper was discontinued on 5 February 1923.[46] Next year, the party merged into the Lithuanian Nationalist Union.[40]

Banaitis returned to publishing in February 1928 when he established weekly newspaper Tautos kelias (Path of the Nation).[47] The newspaper supported the coup d'état of December 1926 that brought the Lithuanian Nationalist Union and President Antanas Smetona to power.[48] However, Banaitis soon lost editorial control to supporters of Prime Minister Augustinas Voldemaras. In June 1928, Banaitis resigned as editor in favor of Algirdas Sliesoraitis, one of the founders of the Iron Wolf organization.[49]

Business ventures

Already in October 1911, Banaitis and lawyer Antanas Petraitis established a small Lithuanian credit union.[50] The number of union members grew from 70 to 429 in January 1915.[51] By the time it was liquidated due to World War I, its balance was 554,000 Rbls.[52] In early 1918, the Council of Lithuania discussed the need for a Lithuanian bank. Banaitis, Martynas Yčas, Jurgis Alekna, and others established the Trade and Industry Bank, which was approved in December 1918 becoming the first Lithuanian bank.[53] Banaitis was elected to its council[54] and obtained 300,000 German marks to purchase weapons and ammunition for the Lithuanian Army from the Germans.[3] Initially, the bank was successful and raised substantial capital from the Lithuanian government, prominent Lithuanians, and Lithuanian Americans.[55] However, due to the hyperinflation of the German mark, mishandled transition to the Lithuanian litas, and general mismanagement, the bank suffered major financial losses.[56] In September 1927, Banaitis, on behalf of the board, officially declared the bank bankrupt.[57]

In February 1919, the first Lithuanian Shipping Company (Lithuanian: Lietuvos laivininkystės bendrovė) was organized by 19 Lithuanians to provide passenger and cargo transportation via the Neman and other rivers in Lithuania.[58] It was later known as the Lithuanian Steamship Corporation (Lithuanian: Lietuvos garlaivių bendrovė). It was chaired by Martynas Yčas and Banaitis was vice-chairman. In March 1920, the company received the first motorized sea ships Jūratė and Kastytis (named after the fairy tale Jūratė and Kastytis) produced by the Friedrich Krupp Germaniawerft.[58] However, cargo transportation around the Baltic Sea was not profitable. Kastytis sank in 1925, and Jūratė was sold in 1926.[59] The river transport was more profitable. The company had several steamships, including Rambynas (built in 1912 in Kiev, capacity 800 passengers), Reinholdas (built in 1912 in Elbing, capacity 320 passengers), Eglė (built in 1883 in Germany, capacity 255 passengers), Gulbė.[60]

In 1927, Banaitis decided to expand on the shipping business to the Lithuanians emigrants headed towards the South America. He applied for a permit to establish a bureau of the Hamburg Südamerikanische Dampfschifffahrts-Gesellschaft, but due to financial difficulties it was approved only in June 1928.[61] A year later, it changed the name to Amerika and represented Lloyd Royal Belge operating from Antwerp.[62] In 1930, due to the Great Depression, Lloyd Royal Belge experienced financial difficulties and was acquired by Compagnie Maritime Belge. The Lithuanian government ordered Banaitis to find a different ship owner to represent and, when he failed to do so, terminated the permit for Amerika in March 1931.[63]

Last years

In 1927, Banaitis became a free non-matriculated student at the Law Faculty of the University of Lithuania. He attended the courses for a year.[64] On 15 May 1928, for contributions to the Lithuanian state, he was awarded the 4th class of the Order of the Lithuanian Grand Duke Gediminas.[65] In the last years, Banaitis worked as the director of the bus station in Kaunas. Appointed in early 1932 as the station director, he worked to relocate the station to a more convenient location. He was instrumental in purchasing the plot of land next to the Kaunas railway station and starting the construction. The new station was opened in 1935.[63]

Banaitis suffered bleeding from a stomach ulcer and died on 4 May 1933 in Kaunas.[3] His funeral was attended by many dignitaries. Fellow signatories of the Act of Independence Antanas Smetona and Pranas Dovydaitis delivered public speeches.[66] He was buried in the old Kaunas cemetery and reburied in the Petrašiūnai Cemetery when the old cemetery was converted into the present-day Ramybė Park.[66] Banaitis left debts that he used to finance his business ventures. Family members had to raise funds to save the mortgaged farm in Vaitiekupiai from being auctioned off by a bank.[67] The farm burned down in 1941; its remnants were destroyed by the authorities of the Lithuanian SSR – stones of the foundations were used to pave roads.[68]

References

- In-line notes

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 7.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 8.

- 1 2 3 Lukšas 2012.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 8–9.

- ↑ Jegelavičius 2002.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 9.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 10.

- 1 2 3 Krikštaponis 2011.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 60.

- ↑ Girininkienė 2013.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 11.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 12.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 13.

- 1 2 3 4 Baršys 2015, p. 14.

- ↑ Tapinas 1997, p. 282.

- ↑ Surblys 2007, p. 283.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 15.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Tapinas 1997, p. 497.

- ↑ Bloznelis & Zimnachaitė 2008, p. 111.

- ↑ Žukas 2002.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 17.

- ↑ Bauža 1934, pp. 447–448.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 16.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 19.

- ↑ Vitkutė 2008, p. 272.

- ↑ Vitkutė 2008, p. 273.

- ↑ Vitkutė 2008, p. 274.

- ↑ Vitkutė 2008, pp. 275, 278.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 21.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 20.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 18.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 18–19.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 24.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 28.

- ↑ Čepėnas 1986, p. 199.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 29.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 31.

- 1 2 Sabaliūnas 1990, p. 11–12.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 35.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 32.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 35–36.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 36, 38.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 37.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 39.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 43.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 43–44.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 44.

- ↑ Terleckas 2004, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Terleckas 2004, p. 34.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 40.

- ↑ Terleckas 2000, p. 10.

- ↑ Terleckas 2000, p. 39.

- ↑ Terleckas 2000, p. 38.

- ↑ Terleckas 2000, p. 46–47.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 41.

- 1 2 Adomavičius 2011, p. 6.

- ↑ Adomavičius 2011, p. 7.

- ↑ Kasparavičius 2015, pp. 39, 62.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 45–46.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 46.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 47.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, pp. 42–43.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 84.

- 1 2 Baršys 2015, p. 48.

- ↑ Baršys 2015, p. 61.

- ↑ Stažytė 2018.

- Bibliography

- Adomavičius, Romas (2011). "Lietuvos Respublikos prekybinio laivyno raida 1921–1936 metais". Istorija. Mokslo darbai (in Lithuanian). 84. ISSN 1392-0456.

- Baršys, Povilas (2015). Vasario 16-osios Akto signataras Saliamonas Banaitis. Iš Lietuvos nacionalinio muziejaus archyvo (in Lithuanian). Vol. 13. Vilnius: Lietuvos nacionalinis muziejus. ISBN 978-609-8039-63-4. ISSN 1648-2859.

- Bauža, Bronius (10 June 1934). "Atsiminimai apie a.a. Saliamoną Banaitį". Naujoji Romuva (in Lithuanian). 178–179. ISSN 1392-043X.

- Bloznelis, Mindaugas; Zimnachaitė, Aldona (2008). "Šv. Kazimiero draugijos kelias" (PDF). Kauno istorijos metraštis (in Lithuanian). 9. ISSN 2335-8734.

- Čepėnas, Pranas (1986). Naujųjų laikų Lietuvos istorija (in Lithuanian). Vol. II. Chicago: Dr. Griniaus fondas. ISBN 5-89957-012-1.

- Girininkienė, Vida; et al., eds. (2013). Sintautai (PDF). Lietuvos valsčiai (in Lithuanian). Vol. 2. Vilnius: Versmė. ISBN 978-9955-589-75-4.

- Jegelavičius, Sigitas (February 2002). "Vasario 16-osios Akto signatarai". Universitas Vilnensis (in Lithuanian). Vilnius University (17). ISSN 1822-1513. Archived from the original on 28 January 2007.

- Kasparavičius, Gediminas (2015). Upių laivyba Lietuvoje 1919−1940 m. (PDF) (Master's) (in Lithuanian). Vytautas Magnus University.

- Krikštaponis, Vilmantas (17–24 August 2011). "Lietuvių tautos, valstybės ir ūkio ugdytojas. Saliamono Banaičio 145-osioms gimimo metinėms". XXI amžius (in Lithuanian). 57, 59. ISSN 2029-1299.

- Lukšas, Aras (20 July 2012). "Pamirštas Tėvynės darbininkas" (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos žinios. Retrieved 23 February 2018.

- Sabaliūnas, Leonas (1990). Lithuanian Social Democracy in Perspective, 1893-1914. Duke University Press. ISBN 9780822310150.

- Stažytė, Karolina (2018). "Saliamonas Banaitis" (in Lithuanian). 15min. Retrieved 25 February 2018.

- Surblys, Alvydas (2007). "Senosios Kauno knygos keliais". Knygotyra (in Lithuanian). 49. ISSN 0204-2061.

- Tapinas, Laimonas; et al., eds. (1997). Žurnalistikos enciklopedija (PDF) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Pradai. ISBN 9986-776-62-7.

- Terleckas, Vladas (2000). Lietuvos bankininkystės istorija 1918-1941 (in Lithuanian). Lietuvos banko Leidybos ir poligrafijos skyrius. ISBN 9986-651-26-3.

- Terleckas, Vladas (2004). "Savitarpio kredito bendrovės (1873–1914 m.) ir jų veiklos bruožai" (PDF). Pinigų studijos (in Lithuanian). 3. ISSN 1392-2637.

- Vitkutė, Justina (2008). "Pirmoji lietuviška gimnazija Kaune (1915–1920 metais)" (PDF). Kauno istorijos metraštis (in Lithuanian). 9. ISSN 2335-8734.

- Žukas, Vladas (14 August 2002). "Banaičio spaustuvė". Visuotinė lietuvių enciklopedija (in Lithuanian). Mokslo ir enciklopedijų leidybos centras.