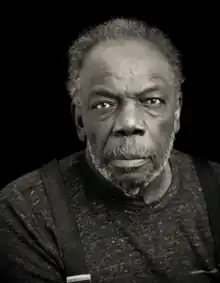

Sam Gilliam | |

|---|---|

by Fredrik Nilsen Studio | |

| Born | November 30, 1933 Tupelo, Mississippi, U.S. |

| Died | June 25, 2022 (aged 88) Washington, D.C., U.S. |

| Alma mater | University of Louisville |

| Known for | Painting |

| Notable work | Double Merge (Carousel I and Carousel II) (1968) Seahorses (1975) Yves Klein Blue (2017) |

| Movement | Washington Color School |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 3, including Leah and Melissa |

Sam Gilliam (/ˈɡɪliəm/ GHIL-ee-əm; November 30, 1933 – June 25, 2022) was an American abstract painter and sculptor. Born in Mississippi and raised in Kentucky, Gilliam spent his entire adult life in Washington, D.C., eventually being described as the "dean" of the city's arts community.[1] Originally associated with the Washington Color School, a group of Washington-area artists that developed a form of abstract art from color field painting in the 1950s and 1960s, Gilliam began to move beyond the movement's core aesthetics of flat fields of color when he introduced sculptural elements to his paintings.[2][3] His work has also been described as lyrical abstraction.[4]

Following his early experiments in color and form, Gilliam became widely known for his draped paintings, which he first developed in the mid-to-late 1960s.[5] These works comprise unstretched painted canvases without stretcher bars, hung or draped like fabric in galleries and outdoor spaces, and Gilliam has been recognized as the first artist to have "freed the canvas" from the stretcher in this way.[6] This innovation has been identified as a major contribution to contemporary art, collapsing the space between painting and sculpture and influencing the development of installation art.[7] Despite becoming a signature style, Gilliam mainly moved on from his draped paintings after the mid-1970s, returning to them primarily for public commissions and several late-career works.[8] In his later work, Gilliam produced art in a range of styles and materials, continuing to experiment with and explore the boundaries between painting, sculpture, and printmaking. Other well-known series of works include his "quilt" paintings from the 1980s, which Gilliam produced by arranging multiple shaped canvases together to resemble the patchwork style of quilts from his childhood,[9] and his extensive series of paintings on canvas with attached painted metal, produced beginning in the 1980s and 1990s.[10]

Although he achieved early critical success, including becoming the first African American artist to represent the United States in an exhibition at the Venice Biennale in 1972, Gilliam's career saw a period of relative decline in attention in the 1980s and 1990s, although he continued to exhibit his work, primarily in Washington.[11] Despite fewer high-profile national and international exhibitions during this period, he was able to sustain his practice in part through public commissions and grant funding. Beginning in the mid-2000s his work began to see renewed critical and institutional attention, and his contributions to contemporary art were reexamined and reevaluated in several notable publications and exhibitions.[8] His late-career milestones included creating a work for permanent display in the lobby of the then-newly opened National Museum of African American History and Culture in 2016, and exhibiting for a second time at the Venice Biennale in 2017.[1] Arne Glimcher, Gilliam's art dealer at Pace Gallery, wrote following his death that, "His experiments with color and surface are right up there with the achievements of Rothko and Pollock."[12]

Biography

Sam Gilliam was born in Tupelo, Mississippi, on November 30, 1933,[13] the seventh of eight children born to Sam and Estery Gilliam.[14] The Gilliams moved to Louisville, Kentucky,[13] shortly after he was born. His father worked on the railroad; his mother cared for the large family. At a young age, Gilliam wanted to be a cartoonist and spent most of his time drawing.[15] He attended Central High School in Louisville and graduated in 1951.[16]

After high school, Gilliam attended the University of Louisville[13] and received his B.A. degree in fine arts in 1955 as a member of the second admitted class of black undergraduate students.[17] In the same year he held his first solo art exhibition at the university. From 1956 to 1958 Gilliam served in the United States Army.[13] He returned to the University of Louisville in 1961 and, as a student of Charles Crodel,[18] received his M.A. degree in painting.[19] While attending college he befriended painter Kenneth Victor Young.[20]

Gilliam listened to his college professor's advice to become a high school teacher and was able to teach art at Washington's McKinley High School.[17][21] Gilliam was devoted to developing his painting during his weekdays reserved for the classroom.[17] In 1962, Gilliam moved to Washington, D.C., after marrying Washington Post reporter Dorothy Butler[22] who was the first African American female reporter at the Washington Post.[17] Later Gilliam lived in Washington, D.C., with his long-time partner, Annie Gawlak. They were married in 2018 after a 35-year partnership.[15]

Career in the 1960s, early 1970s

During the social upheaval of the 1960s in the United States, Gilliam began painting works that were abstract but still made bold, declarative statements, inspired by the specific conditions of the African-American experience.[23] This was at a time that "abstract art was said by some to be irrelevant to black African life."[24] Abstraction remained a critical issue for artists such as Gilliam. His early style developed from brooding figural abstractions into large paintings of flatly applied color, pushing Gilliam to eventually remove the easel by eliminating the stretcher. During this time period, Gilliam painted large color-stained canvases, which he draped and suspended from the walls and ceilings, comprising some of his best-known artwork.[25][26]

Gilliam was influenced by German Expressionists such as Emil Nolde, Paul Klee, and the American Bay Area Figurative School artist Nathan Oliveira. His early influences included Morris Louis and Kenneth Noland. He said that he found many clues about how to go about his work from Vladimir Tatlin, Frank Stella, Hans Hofmann, Georges Braque, Pablo Picasso, and Paul Cézanne. In 1963, Thomas Downing, an artist who identified himself with the Washington Color School, introduced Gilliam to this new school of thought. Around 1965, Gilliam became the first painter to introduce the idea of the unsupported canvas. He was inspired to do this by observing laundry hanging outside his Washington studio.[14] His drape paintings were suspended from ceilings or arranged on walls or floors, representing a sculptural third dimension in painting. Gilliam said that his paintings are based on the fact that the framework of the painting is in real space. He was attracted to its power and the way it functioned. Gilliam's draped canvases change in each environment where they are arranged and frequently he embellished the works with metal, rocks, and wooden beams.[27] He received countless public and private commissions for these draped canvases which earned him the title of the "father of the draped canvas".[28] One of his last, and largest, works within this series was titled Seahorses (1975), made for the Philadelphia Museum of Art.[28] The work consisted of six parts and was made of hundreds of feet of canvas hung on the outside walls of the museum.[28]

During the 1960s, Gilliam also experimented with beveled-edge paintings, often using acrylic paint to color over the edges of the canvas onto the frames of the painting. Similarly to his drape paintings, these beveled paintings blurred the line between sculpture and paintings, while retaining a distinct commitment to abstraction.[29]

In 1971, he boycotted an event at the Whitney Museum, in New York, in support of and in solidarity with the Black Emergency Cultural Coalition as a protest against the museum for failing to consult with black art experts in selecting art for the show.[30]

In 1972, Gilliam represented the United States at the 36th Venice Biennale in a group show curated by Walter Hopps. His draped canvas Baroque Cascade (1968) was exhibited at the show, a multi-canvas installation that stretched over 75 feet before being hung from the rafters in the exhibition hall. The work had originally been shown at the Corcoran Gallery in 1969 in a show of Gilliam's work organized by Hopps. Gilliam was the first African-American artist to show at the Biennale for the United States, although no African-American artist represented the US with a solo show until Robert Colescott's solo exhibition in 1997.[14][26][31][32][33]

Career in the 1970s and 1980s

In 1975, Gilliam veered away from the draped canvases, and became influenced by jazz musicians such as Miles Davis and John Coltrane.[34] He started producing dynamic geometric collages, which he called "Black Paintings" because they are painted in shades of black.[22] Works like Rail (1977) typify this style, with thick layers of black paint and outlines of sharp geometric shapes.[29]

In the 1980s Gilliam's style changed dramatically once more, transitioning to paintings reminiscent of African patchwork quilts from his childhood, using an improvisational approach.[35] These works often included multiple canvases carved into geometric shapes and combined into a single form.[36] The transition between his "Black Paintings" and quilt-inspired paintings can be seen in his Wild Goose Chase series.[28]

Later career

In the late 1980s and 1990s, Gilliam was largely overlooked by the institutional art world. He showed his work very infrequently outside of Washington, D.C. during this time, as a result of both his desire to work in his own community and a decline in interest from critics and museums in New York. Despite this isolation from a broader audience, he continued to produce paintings in new forms and developed new approaches to abstraction, including experimentation with metal forms and the use of washi paper to create sculptural works, and exhibited extensively in Washington, D.C. and across the Southeast United States.[37] In 2019, journalist Greg Allen wrote about Gilliam's insulation from mainstream art spaces in Art in America, saying "if, at some periods in his extensive career, Gilliam seemed invisible, it’s simply because people refused to see him."[32] Gilliam himself said in 1989 that "I’ve learned the difference between what is really good and real for me and what is something that I dreamed would be real and good for me. I’ve learned to — I don’t mean to say I’ve learned to love this — but I’ve learned to accept this, the matter of staying here."[8]

Beginning in the 2000s, Gilliam's career saw a marked resurgence in critical and institutional attention, starting with his first full-scale retrospective at the Corcoran Gallery in 2005.[38] In 2012, Los Angeles-based gallerist David Kordansky visited Gilliam in Washington with the artist Rashid Johnson to offer representation and begin planning an exhibition, a request that reportedly moved Gilliam to tears. Kordansky subsequently helped place major works by the artist in high-profile institutions like the Museum of Modern Art and Metropolitan Museum of Art and organized several exhibitions of Gilliam's work.[39] Throughout the 2000s and 2010s Gilliam participated in a large number of high-profile solo and group shows, including exhibiting at the Venice Biennale for a second time in 2017, in the Giardini's central pavilion for the show Viva Arte Viva.[8] His work Yves Klein Blue (2017), a large-scale draped painting, was hung outside the entrance of the venue.[33][40] His first European retrospective, Sam Gilliam: Music of Color, was hosted in 2018 by the Kunstmuseum Basel.[41] In 2019 Gilliam acquired representation through a New York-based gallery for the first time, Pace Gallery.[37]

In 2022, one month before his death, he debuted a series of tondo paintings in a solo show at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C. The abstract paintings, the first of Gilliam's works in the tondo form, are circular canvases in beveled frames containing fields of color, sometimes overflowing onto the frames themselves.[42] The paintings' beveled frames represented a return to a form the artist had originally explored in the 1960s and 1970s.[29]

Recognition

Gilliam had many commissions, grants, awards, and honorary doctorates.

His honors included eight honorary doctorates, and the Kentucky Governor's Award in the Arts. He received several National Endowment for the Arts grants, the Longview Foundation Award, and a Guggenheim Fellowship. He also received the Art Institute of Chicago's Norman W. Harris Prize, and an Artist's Fellowship from the Washington Gallery of Modern Art.[43] He was named the 2006 University of Louisville Alumnus of the Year.[43]

In 1987 Gilliam was selected by the Smithsonian Art Collectors Program to produce a print to celebrate the opening of the S. Dillon Ripley Center in the National Mall. He donated his talent to produce In Celebration, a 35-color limited-edition serigraph that highlighted his trademark use of color. The sale benefited the Smithsonian Associates, the continuing education branch of the larger Smithsonian Institution.[44] In early 2009, he again donated his talents to the Smithsonian Associates to produce a 90-color serigraph entitled Museum Moment, which he described as "a celebration of art".[45]

In April 2003, a dedication of the installation of Gilliam's work, Matrix Red-Matrix Blue, was held at Rutgers Law School, Newark.[46] In May 2011, his work From a Model to a Rainbow was installed in the Washington Metro Underpass at 4th and Cedar, NW.[47]

In January 2015, Gilliam was awarded the Medal of Art by the U.S. State Department for his longtime contributions to Art in Embassies and cultural diplomacy.[16] His work was shown in embassies and diplomatic facilities in over 20 countries during his career.[31]

Personal life

In 1962, Gilliam married Dorothy Butler, a Louisville native and the first African-American female columnist at The Washington Post. They divorced in the 1980s but have three daughters (Stephanie, Melissa, and Leah) and also have three grandchildren. After the divorce he met Annie Gawlak, owner of the former G Fine Art gallery in Washington, D.C. The pair were married in 2018 after having been together in a 35-year partnership.[48]

Gilliam died of renal failure at his home in Washington, D.C., on June 25, 2022, at the age of 88.[49]

Selected public artwork

- Solar Canopy (1986)

Solar Canopy is an aluminum sculpture made by Gilliam in 1986. It is a large 34'x 12'x 6" feet painted sculpture located at York College, City University of New York's Academic Core Lounge on the third floor across a huge open window. It is suspended from the ceiling at 60 ft (18 m) high. The artwork is made up of painted geometric shapes with many vibrant colors, some having a solid color while others have a tie-dye effect painted on them. The artwork is connected together in a horizontal diagonal with a circular shape in the middle. The circular middle is red on the outside and underneath is painted with many different colors in a tie-dye effect. It also has small blocks under it painted in solid colors of red, orange, blue, and yellow. Attached to some of the small blocks are triangular blocks.[50]

- Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue (1991)

Located at the Jamaica Center train station (E,J,Z) Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue is a large aluminum sculpture mounted high outside on a wall above one of the entrances.[51] The Metropolitan Transportation Authority Arts for Transit project commissioned the work in 1991. It is made up of geometric shapes painted in solid primary colors (red, yellow, blue). The shape of the overall sculpture is circular, with the outer part being blue while the inner parts are red and yellow. In the artist's words, the work "calls to mind movement, circuits, speed, technology, and passenger ships...the colors used in the piece... refer to colors of the respective subway lines. The predominant use of blue provides one with a visual solid in a transitional area that is near subterranean."[52]

Exhibitions

Gilliam staged a large number of solo shows in the United States and internationally. His solo shows include Paintings by Sam Gilliam (1967), The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.;[53] Projects: Sam Gilliam (1971), Museum of Modern Art, New York;[54] Red & Black to “D”: Paintings by Sam Gilliam (1982–1983), Studio Museum in Harlem, New York;[55] Sam Gilliam: Construction (1996), Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky;[56] Sam Gilliam in 3-D (1998-1999), Kreeger Museum, Washington, D.C.;[57] Sam Gilliam: A Retrospective (2005–2007), originating at the Corcoran Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.;[58] Sam Gilliam (2017), Seattle Art Museum;[59] and Sam Gilliam: The Music of Color (2018), Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland, the artist's first solo museum exhibition in Europe.[60] Following Gilliam's decision to join David Kordansky Gallery and Pace Gallery in 2012 and 2019, respectively, he began staging multiple solo gallery exhibitions in relatively quick succession, including Hard Edge Paintings 1963-1966 (2013) at Kordansky in Los Angeles, curated by artist Rashid Johnson;[39] Green April (2016), also in Los Angeles;[61] Existed Existing (2020) at Pace, his first solo exhibition of new work in New York in over 20 years;[62] and Sam Gilliam (2021), his first solo exhibitions in Asia, hosted at Pace's Seoul and Hong Kong locations.[63][64]

The first major American museum retrospective of Gilliam's work in nearly two decades was scheduled to open in 2020 at the Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden in Washington, D.C., but was rescheduled to 2022 due to the COVID-19 lockdowns. The show, Sam Gilliam: Full Circle, opened in May 2022 as an exhibition of works the artist had produced almost exclusively during the COVID-19 pandemic, instead of a broader retrospective as originally planned. Full Circle was Gilliam's final show during his lifetime, opening one month before his death.[65][66]

The first posthumous solo exhibition of Gilliam's work, Late Paintings, opened at Pace's London gallery in October 2022. Late Paintings was the final show Gilliam had planned during his life and was his first solo exhibition in the United Kingdom.[67]

He also participated in many group exhibitions, including The De Luxe Show (1971), DeLuxe Theater, Houston;[68] the 36th Venice Biennale (1972);[14] Gilliam/Edwards/Williams: Extensions (1974), Wadsworth Atheneum, Hartford, Connecticut;[69] the Marrakech Biennale (2016);[70] and the 57th Venice Biennale (2017).[71]

Notable works in public collections

- Long Green (1965), Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[72]

- Shoot Six (1965), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[73]

- They Sail (1966), The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.[74]

- Red Petals (1967), The Phillips Collection, Washington, D.C.[75]

- Carousel State (1968), Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York[76]

- Double Merge (Carousel I and Carousel II) (1968), Museum of Fine Arts, Houston, and Dia Art Foundation, New York (jointly owned)[77]

- Relative (1968), National Gallery of Art, Washington, D.C.[78]

- Restore (1968), Speed Art Museum, Louisville, Kentucky[79]

- 10/27/69 (1969), Museum of Modern Art, New York[80]

- April 4 (1969), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[81]

- Dakar I (1969), Philadelphia Museum of Art[82]

- Green April (1969), Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland[83]

- Light Depth (1969), Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[84]

- Swing (1969), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[85]

- Basque 1 Range (1970), Pérez Art Museum Miami[86]

- Change (1970), Mumok, Vienna, Austria[87]

- Change (1970), Louisiana Museum of Modern Art, Humlebæk, Denmark[88]

- Leaf (1970), Dallas Museum of Art[89]

- Simmering (1970), Tate, London[90]

- Carousel Merge (1971), Walker Art Center, Minneapolis[91]

- Carousel Merge 2 (1971), Milwaukee Art Museum[92]

- Day Tripper (1971), Carnegie Museum of Art, Pittsburgh[93]

- Rondo (1971), Kunstmuseum Basel, Switzerland[94]

- Wide Narrow (1972), Rose Art Museum, Waltham, Massachusetts[95]

- "A" and the Carpenter I (1973), Art Institute of Chicago[96]

- N°1 D (1977), Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris[97]

- Rail (1977), Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[98]

- Eiler Blues (1978), Madison Museum of Contemporary Art, Wisconsin[99]

- Untitled (Black) (1978), Whitney Museum, New York[100]

- Triple Variants (1979), Richard B. Russell Federal Building, Atlanta (General Services Administration)[101]

- The Arc Maker I & II (1981), Detroit Institute of Arts[102]

- Master Builder Pieces and Eagles (1981), Studio Museum in Harlem, New York[103]

- Red & Black (1981), Indianapolis Museum of Art[104]

- To Braque for Mantelpieces (1982), Cleveland Museum of Art[105]

- Sculpture with a D (1980-1983), Davis station, Massachusetts Bay Transportation Authority, Boston[106]

- Solar Canopy (1986), York College, City University of New York[107]

- Purple Antelope Space Squeeze (1987), Milwaukee Art Museum[108]

- The Petition (1990), Smithsonian American Art Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[109]

- Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue (1991), Jamaica Center–Parsons/Archer station, Metropolitan Transportation Authority, New York[110]

- Running Naked (1991), Minneapolis Institute of Art[111]

- Daily Red (1998), Anacostia Community Museum, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[112]

- Graining (1998), Kreeger Museum, Washington, D.C.[113]

- Norfolk Keels (1998), Chrysler Museum of Art, Norfolk, Virginia[114]

- Chair Key (2002), Philander Smith College, Little Rock, Arkansas[115]

- Blue (2009), Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts, Philadelphia[116]

- From Model to Rainbow (2011), Takoma station, Washington Metropolitan Area Transit Authority[117]

- Yet Do I Marvel (Countee Cullen) (2016), National Museum of African American History and Culture, Smithsonian Institution, Washington, D.C.[118]

Citations

- 1 2 O'Sullivan, Michael (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, abstract artist who went beyond the frame, dies at 88". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on November 29, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Panero, James (August 19, 2020). "'Sam Gilliam' Review: Flowing Color, Billowing Canvas". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on November 27, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Cohen, Jean Lawlor; Cohen, Jean Lawlor (June 26, 2015). "When the Washington Color School earned its stripes on the national stage". The Washington Post. ISSN 0190-8286. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam Biography". Ogden Museum of Southern Art. Archived from the original on March 29, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Smee, Sebastian (June 28, 2022). "Sam Gilliam never fought the canvas. He liberated it". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on September 22, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Di Liscia, Valentina (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, Groundbreaking Abstractionist, Dies at 88". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on October 26, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Rappolt, Mark (July 21, 2014). "Feature: Sam Gilliam". ArtReview. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- 1 2 3 4 Smith, Roberta (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, Abstract Artist of Drape Paintings, Dies at 88". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ↑ Bryan-WIlson, Julia (November 2023). "The Rake and the Furrow". Artforum. 62 (3). Archived from the original on December 17, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Basciano, Oliver (June 30, 2022). "Sam Gilliam obituary". The Guardian. Archived from the original on June 14, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ Capps, Kriston (July 8, 2022). "Painter Sam Gilliam Spent His Entire Career in Washington, D.C. Here's How the City Sustained Him When the Art World Wasn't Watching". Artnet. Archived from the original on February 9, 2023. Retrieved December 17, 2023.

- ↑ "Arne Glimcher Recounts His Friendship with Sam Gilliam". Pace Gallery. June 27, 2022. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sam Gilliam – Bio". www.phillipscollection.org. Archived from the original on November 30, 2020. Retrieved August 23, 2020.

- 1 2 3 4 Kinsella, Eileen (January 2, 2018). "At Age 84, Living Legend Sam Gilliam Is Enjoying His Greatest Renaissance Yet". Retrieved June 22, 2018.

- 1 2 "Beer with a Painter: Sam Gilliam". Hyperallergic. March 19, 2016. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- 1 2 "SAM GILLIAM Medal of Arts 2015". Art in Embassies. U.S. Department of State. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

Sam Gilliam was awarded the Medal of Art for his longtime contributions to Art in Embassies and cultural diplomacy on January 21, 2015. ... In 1951, Gilliam graduated from Central High School in Louisville.

- 1 2 3 4 Brown, Jackson (2017). "Sam Gilliam". Callaloo. 40 (5): 59–68. doi:10.1353/cal.2017.0155. ISSN 1080-6512. S2CID 201765406.

- ↑ "Man of Constant Color: SAM GILLIAMââ'¬â"¢S ABSTRACT ART COMES HOME FOR A RETROSPECTIVE – LEO Weekly".

- ↑ Sam Gilliam Jr., A Study of Different Uses of Solid Forms in Painting, A Thesis Submitted to the Graduate School of the University of Louisville, 1961.

- ↑ "Kenneth Victor Young: Exploring Space". East City Art. March 11, 2021. Archived from the original on June 25, 2021. Retrieved September 2, 2021.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam – Biography". rogallery.com. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- 1 2 "Sam Gilliam". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam (b.1932)". The Melvin Holmes Collection of African American Art. Retrieved August 19, 2020.

- ↑ Russell, John (1983). "Art". The New York Times.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam facts, information, pictures | Encyclopedia.com articles about Sam Gilliam". www.encyclopedia.com. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- 1 2 "Basking in Sam Gilliam's Endless Iterations". Hyperallergic. November 29, 2019. Retrieved May 9, 2020.

- ↑ Tate. "'Simmering', Sam Gilliam, 1970 | Tate". Tate. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 "Sam Gilliam | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Michalarou, Efi. "ART CITIES: N.York-Sam Gilliam". dreamideamachine ART VIEW. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 8, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam's Biography". The HistoryMakers. Retrieved March 9, 2021.

- 1 2 Capps, Kriston (March 27, 2015). "Return to Splendor". WCP. Washington City Paper. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved July 22, 2022.

- 1 2 Allen, Greg (February 2019). "Color in Landscape". Art in America. ARTNews. Archived from the original on June 28, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- 1 2 Campbell, Andrianna (July 11, 2017). "Sam Gilliam". Artforum International. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam – Biography". rogallery.com. Retrieved March 10, 2019.

- ↑ Beardsley, John (1989). Sam Gilliam: Recent Paintings November 15 – December 16, 1989. Ingalls Library clipping file, The Cleveland Museum of Art: Barbara Fendrick Gallery. pp. n.p. (exhibition booklet without pages).

- ↑ "Remembering Sam Gilliam". Pace Gallery. June 27, 2022. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved July 7, 2022.

- 1 2 Greenberger, Alex (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, Groundbreaking Artist Who Brought Abstraction Into the Third Dimension, Dies at 88". ARTNews. Archived from the original on June 27, 2022. Retrieved June 29, 2022.

- ↑ Binstock, Jonathan P. (December 5, 2005). Sam Gilliam : a retrospective catalogue. Univ of California Press. ISBN 9780520246348. OCLC 835849576.

- 1 2 Griffin, Jonathan (September 10, 2014). "The New Dealer". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 17, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ↑ "La Biennale di Venezia – Artists". www.labiennale.org. Archived from the original on June 29, 2017. Retrieved February 22, 2017.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam". Kunstmuseum Basel. Archived from the original on July 8, 2022. Retrieved July 17, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam: Full Circle". Hirshhorn. Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- 1 2 "Sam Gilliam". louisville.edu. Retrieved July 22, 2018.

- ↑ "In Celebration, 1987 by Sam Gilliam". The Smithsonian Associates. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Museum Moment, 2009 by Sam Gilliam". The Smithsonian Associates. Retrieved August 9, 2013.

- ↑ "Rutgers Law School News" (PDF). Rutgers Law School. April 1, 2003. Retrieved July 11, 2017.

- ↑ "Norton to Recognize World Renowned Artist Sam Gilliam During Metro Dedication Ceremony, Saturday". Congresswoman Eleanor Holmes Norton. June 10, 2011. Retrieved March 11, 2017.

- ↑ Capps, Kriston (March 27, 2015). "Return to Splendor". Washington City Paper. Washington DC. Retrieved March 27, 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Roberta (June 27, 2022). "Sam Gilliam, Abstract Artist of Drape Paintings, Dies at 88". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 27, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam, Solar Canopy, 1986", Unforgotten Masterpieces.

- ↑ "CultureNOW – Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue: Sam Gilliam and MTA Arts & Design". culturenow.org. Retrieved December 26, 2017.

- ↑ "Jamaica Center-Parsons-Archer | Sam Gilliam", MTA Arts & Design, MTA.

- ↑ "Remembering Sam Gilliam". The Phillips Collection. Archived from the original on July 19, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Projects: Sam Gilliam". MoMA. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on June 9, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam". Studio Museum in Harlem. September 10, 2020. Archived from the original on July 7, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Prominent African American Artist, Sam Gilliam, Dies at the Age of 88" (PDF). Speed Art Museum. Archived (PDF) from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam in 3-D". Kreeger Museum. Archived from the original on October 25, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam: a retrospective". Corcoran Gallery of Art. Archived from the original on October 14, 2021. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam". SAM. Seattle Art Museum. Archived from the original on January 24, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam: Music of Color". Kunstmuseum Basel. Archived from the original on October 7, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Rodney, Seph (July 11, 2016). "A Black Painter Who Found Aesthetic Liberty in the 1960s". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on June 7, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam: Existed Existing". Pace Gallery. Archived from the original on May 31, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam". Pace Gallery. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam". Pace Gallery. Archived from the original on June 30, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "A Major Sam Gilliam Retrospective Is Coming to the Hirshhorn | Washingtonian (DC)". Washingtonian. February 7, 2020. Retrieved May 1, 2020.

- ↑ Rudig, Stephanie (May 26, 2022). "This D.C. Artist Painted Furiously Through The Pandemic. The Hirshhorn Is Now Displaying Their Work". DCist. WAMU. Archived from the original on May 27, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Sam Gilliam: Late Paintings". Pace Gallery. Archived from the original on October 11, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Greenberger, Alex (August 11, 2021). "How a 'Revolutionary' Racially Integrated Art Exhibition in Texas Changed the Game". ARTnews. Archived from the original on July 2, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Allen, Greg (February 1, 2019). "Sam Gilliam: Color in Landscape". Art in America. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Vartanian, Hrag (May 6, 2016). "Tracing the Contours of Power at the Marrakech Bienniale". Hyperallergic. Archived from the original on July 22, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ Campbell, Andrianna (July 11, 2017). "Sam Gilliam discusses his work, showing in the Venice Biennale, and the NEA". Artforum. Archived from the original on October 22, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Long Green". Anacostia Community Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on June 16, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ↑ "Shoot Six". NGA. National Gallery of Art. 1965. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "They Sail". Phillips. The Phillips Collection. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Red Petals". Phillips. The Phillips Collection. Retrieved July 19, 2022.

- ↑ "Carousal State". MetMuseum. Metropolitan Museum of Art. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Double Merge (Carousel I and Carousel II)". MFAH. Museum of Fine Arts, Houston. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Relative". NGA. National Gallery of Art. 1968. Archived from the original on March 21, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Restore". Speed. Speed Art Museum. Archived from the original on June 24, 2016. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "10/27/69". MoMA. Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on December 15, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "April 4 - Sam Gilliam". SAAM. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on July 31, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Dakar I". PhilaMuseum. Philadelphia Museum of Art. Archived from the original on December 2, 2021. Retrieved August 8, 2022.

- ↑ "Green April". Kunstmuseum Basel (in German). Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Light Depth". Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Swing". SAAM. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on February 27, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Basque 1 Range". PAMM. Pérez Art Museum Miami. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Change". Mumok. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "24 I FOKUS - NYE VÆRKER I SAMLINGEN". Louisiana (in Danish). Louisiana Museum of Modern Art. Archived from the original on January 6, 2023. Retrieved January 6, 2023.

- ↑ "Leaf". DMA. Dallas Museum of Art. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Simmering". Tate. Archived from the original on November 29, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Carousel Merge". Walker. Walker Art Center. Archived from the original on December 5, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Carousel Merge 2". MAM. Milwaukee Art Museum. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Day Tripper". CMOA. Carnegie Museum of Art. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Rondo". Kunstmuseum Basel (in German). Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "Wide Narrow". RAM. Rose Art Museum. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ ""A" and the Carpenter I". AIC. Art Institute of Chicago. 1973. Archived from the original on November 13, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "N°1 D". MAM Paris. Musée d'Art Moderne de Paris. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Rail". Hirshhorn Museum and Sculpture Garden. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on April 15, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Eiler Blues". MMoCA. Madison Museum of Contemporary Art. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Untitled (Black)". Whitney. Whitney Museum. Archived from the original on July 4, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Triple Variants". GSA. General Services Administration. Archived from the original on June 29, 2022. Retrieved November 10, 2022.

- ↑ "The Arc Maker I & II". DIA. Detroit Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on June 15, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Master Builder Pieces and Eagles". Studio Museum. The Studio Museum in Harlem. April 23, 2021. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Red & Black". IMA. Indianapolis Museum of Art. Archived from the original on November 6, 2022. Retrieved November 6, 2022.

- ↑ "To Braque for Mantelpleces". ClevelandArt. Cleveland Museum of Art. October 30, 2018. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "On the red line" (PDF). MBTA. p. 3. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ↑ "Solar Canopy". York College. City University of New York. Archived from the original on April 18, 2021. Retrieved June 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Purple Antelope Space Squeeze". MAM. Milwaukee Art Museum. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "The Petition". SAAM. Smithsonian American Art Museum. Archived from the original on June 13, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Jamaica Center Station Riders, Blue". MTA. Metropolitan Transportation Authority. Archived from the original on October 27, 2021. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Running Naked". MIA. Minneapolis Institute of Arts. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Daily Red". Anacostia Community Museum. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on February 13, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Graining". Kreeger Museum. Archived from the original on October 22, 2020. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "Norfolk Keels". Chrysler Museum of Art. Archived from the original on November 27, 2023. Retrieved November 27, 2023.

- ↑ "Chair Key". Philander Smith College African American Art. Philander Smith College. October 13, 2014. Archived from the original on November 15, 2022. Retrieved November 15, 2022.

- ↑ "Blue". PAFA. Pennsylvania Academy of the Fine Arts. February 19, 2018. Archived from the original on May 28, 2022. Retrieved May 28, 2022.

- ↑ "From Model to Rainbow". WMATA. Archived from the original on July 9, 2022. Retrieved July 11, 2022.

- ↑ "Yet Do I Marvel (Countee Cullen)". NMAAHC. Smithsonian Institution. Archived from the original on August 7, 2023. Retrieved August 7, 2023.

General and cited references

- Sam Gilliam: a retrospective, October 15, 2005, to January 22, 2006, Corcoran Gallery of Art

- Binstock, Jonathan P., and Sam Gilliam. 2005. Sam Gilliam: a retrospective. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Sam Gilliam papers, 1958–1989, Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution

- AskArt lists 52 references to Sam Gilliam

- Washington Art, catalog of exhibitions at State University College at Potsdam, NY & State University of New York at Albany, 1971, Introduction by Renato G. Danese, printed by Regal Art Press, Troy NY.

External links

- Sam Gilliam Papers, 1957–1989. Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution.

- "Sam Gilliam" files, Thelma & Bert Ollie Memorial Collection of Abstract Art by Black Artists: Files for Research and Education, Museum Archives, Saint Louis Art Museum

- Gilliam's Newest Work Inspires Dickstein Shapiro, Washingtonian magazine

- Sam Gilliam at the National Gallery of Art

- Sam Gilliam Lecture, March 9, 1977, from Maryland Institute College of Art's Decker Library, Internet Archive

- Sam Gilliam at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, Minneapolis, MN

- Sam Gilliam "Existed Existing" at Pace Gallery