| Santa Marta Formation | |

|---|---|

| Stratigraphic range: Santonian-Campanian | |

| |

| Type | Geological formation |

| Unit of | Marambio Group |

| Sub-units | Alpha Member, Beta Member |

| Underlies | Snow Hill Island Formation |

| Overlies | Hidden Lake Formation |

| Thickness | 1,000 m (3,300 ft) |

| Lithology | |

| Primary | Mudstone, sandstone |

| Other | Siltstone, tuff |

| Location | |

| Coordinates | 63°00′S 57°00′W / 63.0°S 57.0°W |

| Approximate paleocoordinates | 60°54′S 67°36′W / 60.9°S 67.6°W |

| Region | James Ross Island |

| Country | |

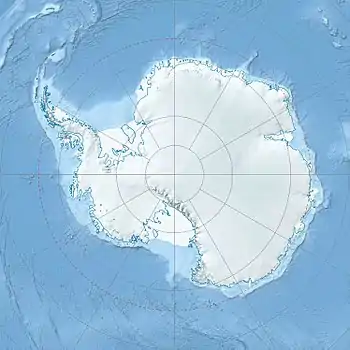

Santa Marta Formation (Antarctica) | |

The Santa Marta Formation is a geologic formation in Antarctica. It, along with the Hanson Formation and the Snow Hill Island Formation, are the only formations yet known on the continent where dinosaur fossils have been found. The formation outcrops on James Ross Island off the coast of the northern tip of the Antarctic Peninsula. In its entirety, the Santa Marta Formation is on average one kilometer thick.

Stratigraphy

The Santa Marta Formation was deposited during the Santonian and Campanian ages of the Late Cretaceous. It overlies the Gustav Group laid down during the Barremian and Santonian ages and is succeeded by the Snow Hill Island Formation of late Campanian age. Together, the Santa Marta Formation, Snow Hill Island Formation, the overlying López de Bertodano Formation (deposited from the late Campanian age of the Late Cretaceous to the early Paleocene epoch of the early Paleogene), and the Sobral Formation (deposited during the early Paleocene) form the Marambio Group.[1]

Originally, the formation was subdivided into three informal members termed the Alpha, Beta, and Gamma members. The names were later changed to the Lachman Crags, Herbert Sound, and Rabot members.[2] The Lachman Crags and Herbert Sound members, named after the areas in which they outcrop, are found in the northern part of James Ross Island. Both members are late Campanian in age. The Lachman Crags Member, the older of the two, is around 500 meters thick. The lower section of the member consists of tuffaceous mudstone while the upper section consists of tuffaceous turbidites formed by underwater avalanches. Bioturbation is evident in tuff beds throughout the member due to the disruption of sediments by benthic life during the time of deposition. The Herbert Sound member is also around 500 meters thick and also can be divided into two distinct sections. Channeled debris flows interbedded with turbides make up the lower portion of the member and are overlain by fine sandstones (followed by coarser sandstones and coquinas) that make up the upper portion of the member.[3]

The depositional environment is thought to have been a system of abyssal fans radiating out from a large river delta. The rapid aggradation of sediments from the delta produced a steep delta slope,[3] which may have resulted in occasional debris flows that formed the turbides. A high degree of tectonic activity in the region at the time may explain the intermittent tuff beds throughout the formation.

The Rabot Member of the Santa Marta Formation is confined to the southeastern part of James Ross Island and dates back to the early to late Campanian. Outcroppings of the member are separated from those of other members in the northern part of the island. Originally the member was regarded as its own formation, and now it is considered to be the lateral equivalent of both the Lachman Crags and Herbert Sound members.[4] Like the Lachman Crags and Herbert Sound members, the Rabot member consists of mudstones and beds of tuff that are often highly bioturbated, and also consists of rare conglomerates. Recently a fourth member has been assigned to the formation called the Hamilton Point Member. The beds of this member used to be considered part of the upper portion of the Rabot member, but now are considered to be their own distinct member.[1]

Flora and fauna

A wide variety of microorganisms inhabited the coastal waters at the time of the deposition of the Santa Marta Formation. Microfossils include ostracods[5] and dinoflagellates.[4]

Invertebrates were also common. Fossils of ammonites can be found in the formation, often embedded vertically in the bedding plane. Originally it was thought that dead ammonites could only be oriented this way in sediment if they were in shallow waters below a certain pressure, but there is evidence to support that due to specific conditions during burial, it was possible for these ammonites to be vertically oriented at greater depths.[6] Ammonite genera present in the formation include Anagaudryceras, Anapachydiscus, Eupachydiscus, Gaudryceras, Maorites, Natalites, Parasolenoceras, Yezoites, and the heteromorph ammonites Ainoceras, Eubostrychoceras, Ryugasella and Baculites. Many bivalve fossils have been found such as Cucullaea, Panopea, Pinna, and Pterotrigonia. Polychaete annelid worms such as Rotularia and gastropods such as the cerithiid sea snail Cerithium have also been discovered in beds within the formation.

Numerous ichnofossils provide evidence of benthic activity, along with previously mentioned bioturbated sediments. Vertical spreite trace fossils have been found as part of fodinichnia dominated ichnocoenosis and were assigned to ichnogenre such as Paradictyodora.[3] Trackways thought to belong to decapods have also been found.[7]

Fish were present, including one of the first frilled sharks, Chlamydoselachus thomsoni.[8] Other marine vertebrates included the small mosasaur Taniwhasaurus antarcticus, previously known as Lakumasaurus antarcticus.[9] The close relation of T. antarcticus to other species of Taniwhasaurus found in New Zealand and Patagonia provides evidence for a Gondwanan endemism.[10]

Antarctopelta oliveroi, an ankylosaur, was discovered in 1986 on the northern part of James Ross Island about 2 kilometers south of Santa Marta Cove in beds that were part of the Santa Marta Formation.[11] It was the first dinosaur found in Antarctica. It may be a possible nodosaur but there has been no formal phylogenic analysis to prove its relationship with other ankylosaurs. Although the formation is made up of only marine deposits, the bodies of these animals along with other debris may have frequently been washed out to sea to later sink to the bottom and be buried by sediment.

Leaves and fragments of plants are commonly found as fossils throughout the formation as well as large tree trunks in the lower members. This is evidence of the forested environment that covered Antarctica during the Late Cretaceous due to the overall warmer global temperature and milder climate. At that time the river delta had much vegetation, and was able to support large herbivores such as Antarctopelta.

See also

References

- 1 2 Pirrie, D.; Crame, J. A.; Lomas, S. A.; Riding, J. B. (1997). "Late Cretaceous stratigraphy of the Admiralty Sound region, James Ross Basin, Antarctica". Cretaceous Research. 18 (1): 109–137. doi:10.1006/cres.1996.0052.

- ↑ Keating, J. M. (1992). "Palynology of the Lachman Crags Member, Santa Marta Formation (Upper Cretaceous) of north-west James Ross Island". Antarctic Science. 4 (3): 293–304. Bibcode:1992AntSc...4..293K. doi:10.1017/S0954102092000452. S2CID 130244948.

- 1 2 3 Olivero, Eduardo B.; Buatois, Luis A.; Scasso, Roberto A. (2004). "Paradictyodora antarctica: a new complex vertical spreite trace fossil from the Upper Cretaceous-Paleogene of Antarctica and Tierra del Fuego, Argentina". Journal of Paleontology. 78 (4): 783–789. doi:10.1666/0022-3360(2004)078<0783:PAANCV>2.0.CO;2. S2CID 131316915.

- 1 2 Sumner, Paul W. (1992). "Dinoflagellate cysts from the Rabot Member (Santa Marta Formation) of eastern James Ross Island". Antarctic Science. 4 (3): 305–310. Bibcode:1992AntSc...4..305S. doi:10.1017/S0954102092000464. S2CID 129854861.

- ↑ Fauth, Gerson; Seeling, Jens; Luther, Axel (2003). "Campanian (Upper Cretaceous) ostracods from southern James Ross Island, Antarctica". Micropaleontology. 49 (4): 95–107. doi:10.2113/49.1.95.

- ↑ Olivero, Eduardo B. (2007). "Taphonomy of ammonites from the Santonian–Lower Campanian Santa Marta Formation, Antarctica: sedimentological controls on vertically embedded ammonites". PALAIOS. 22 (6): 586–597. Bibcode:2007Palai..22..586O. doi:10.2110/palo.2005.p05-118r. hdl:11336/156233. S2CID 131436435.

- ↑ Pirrie, D.; Feldmann, R. M.; Buatois, L. A. (2004). "A new decapod trackway from the Upper Cretaceous, James Ross Island, Antarctica". Palaeontology. 47 (1): 1–12. doi:10.1111/j.0031-0239.2004.00343.x.

- ↑ Richter, Martha; Ward, David J. (1990). "Fish remains from the Santa Marta Formation (Late Cretaceous) of James Ross Island, Antarctica". Antarctic Science. 2 (1): 67–76. Bibcode:1990AntSc...2...67R. doi:10.1017/S0954102090000074. S2CID 140650195.

- ↑ Caldwell, M. W.; Konishi, T.; Obata, I.; Muramoto, K. (2008). "New species of Taniwhasaurus (Mosasauridae, Tylosaurinae) from the upper Santonian-lower Campanian (Upper Cretaceous) of Hokkaido, Japan". Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology. 28 (2): 339–348. doi:10.1671/0272-4634(2008)28[339:ANSOTM]2.0.CO;2. S2CID 129446036.

- ↑ Martin, J. E.; Fernández, M. (2007). "The synonymy of the Late Cretaceous mosasaur (Squamata) genus Lakumasaurus from Antarctica with Taniwhasaurus from New Zealand and its bearing upon faunal similarity within the Weddellian Province". Geological Journal. 42 (2): 203–211. doi:10.1002/gj.1066. S2CID 128429649.

- ↑ Olivero E. B., Gasparini Z., Rinaldi C. A. and Scasso R. (1991) First record of dinosaurs in Antarctica (Upper Cretaceous, James Ross Island): paleogeographical implications, in Thomson M. R. A., Crame J. A. and Thomson J. W. (eds), Geological Evolution of Antarctica. Cambridge University Press, Cambridge: 617–622. ISBN 978-0-521-37266-4