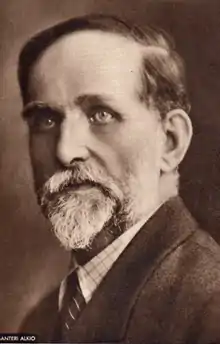

Santeri Alkio | |

|---|---|

| |

| President of the Centre Party of Finland | |

| In office 1918–1919 | |

| Preceded by | Filip Saalasti |

| Succeeded by | Petter Vilhelm Heikkinen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 17 June 1862 Laihia, Grand Duchy of Finland, Russian Empire |

| Died | 24 July 1930 (aged 68) Laihia, Finland |

| Political party | Centre Party |

| Spouse(s) | Susanna Mannila (1884–1894), Anna Augusta Falenius (1896–1930) |

| Occupation | politician, political ideologist |

| Profession | Writer |

Santeri Alkio (born Aleksander Filander; 17 June 1862 – 24 July 1930) was a Finnish politician, author and journalist. He is also considered to be the ideological father of the Finnish Centre Party.

History

Alkio was born in Laihia; his parents were Juho and Maria (née Jakku) Filander. He married teacher Anna Augusta Falenius in 1896.

Initially Santeri Alkio was active in the Young Finnish Party, but in the end decided it was too liberal for the farming population; urbanized parties did not, in his estimation, pay enough attention to the causes that were most important to farmers. To keep the agrarian folk from becoming ensnared by socialism, he founded the Etelä-Pohjanmaan Nuorsuomalainen Maalaisliitto ("Young-Finnish Countrymens' Union of Southern Ostrobothnia"), which he later fused into the less ideological Maalaisväestön liitto ("Union of the Rural Population", later Centre Party of Finland). Alkio became the chief ideologue of the Maalaisliitto, and is still considered the father of the party in spirit. The party still refers to alkioish tendencies in some of its factions.

Alkio was a member of the Finnish House of Representatives from 1907 to 1908 and again from 1914 to 1922. He was vice-chairman of the Eduskunta in 1917 and 1918. When the October Revolution began in Russia, the Bolshevik Declaration of the Rights of the Peoples of Russia led to controversy in the Finnish parliament on how to respond. Based on Alkio's proposal, the Parliament of Finland assumed sovereignty in Finland on 15 November, eventually leading to the Finnish Declaration of Independence on 6 December (Independence Day of Finland).[1] After independence, Alkio continued in parliament as the minister of social affairs from 1919 to 1920. He was the minister of social affairs of the Vennola government from (15 August 1919 – 15 March 1920). An ardent temperance-movement activist, he participated in drafting the Finnish Prohibition and also was the minister responsible for the confirmation of president K. J. Ståhlberg.

Alkio was an extremely prolific author. He founded the newspaper Ilkka and was its editor through the years 1906–1930.

His likeness graced a Finnish stamp on 17 July 1962.

Alkio's views

Alkio was a fervent spokesman for democracy and Finnish national independence. He led the youth association movement, which above all wanted to defend the values of rural life and foster temperance and healthy living, a desire the movement held in common with the coeval Christian revivalist and labor movements.

Despite his Christian background, Alkio was a strong opponent of the state church. In 1906 Alkio wrote that "We want to liberate the beautiful and simple teachings of Jesus from the tyranny of theology and that is why we would like to withdraw the support of the state from one confession and to proclaim it to all."

As a nationalist, Alkio supported the independent Senate of Svinhufvud. During the summer of 1917, he had supported usurping the highest power in the land from Russia via the Power of Government Act (Lex Tulenheimo) while the parties on the right still opposed it.

Alkio thought the red revolt supported by Russian soldiers was an attempt to return Finland to Soviet Russia: "It [the revolt] is meant to set Finnish independence at nought." (Sen [kapinan] tarkoituksena on tehdä tyhjäksi Suomen itsenäisyys.)

Alkio was also a pacifist. He attributed this to the influence of Mahatma Gandhi. On 15 January 1920, he wrote in the newspaper Maan Ääni that Europe should consider the question of the United States of Europe. This article made him one of the first important proponents of European integration. He died in Laihia.

Bibliography

- Teerelän perhe (1887)

- Puukkojunkkarit – kuvauksia nyrkkivallan ajalta (1894) (full text)

- Murtavia voimia (1896) (full text)

- Jaakko Jaakonpoika (1913) (full text)

- Uusi aika (1914)

- Patriarkka (1916)

- Ihminen ja kansalainen (1919)

- Yhteiskunnallista ja valtiollista (1919)

- Maalaispolitiikkaa I–II (1919, 1921)

- Kootut teokset I–XIII (1919–1928)

- Valitut teokset (1953)

References

- ↑ "iJari Korkki: Täyttääkö Suomi sata vuotta jo ensi viikolla? – Uusi itsenäisyysjulistus keskiviikkona". Yle Uutiset (in Finnish). 10 November 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2020.