.jpg.webp) Examples on a ceiling at Yasaka Shrine |

| Votive talismans designed for the home |

|---|

| Ofuda, and Jingū taima when from Ise Jingu |

| Votive paper slips applied to the gates of shrines |

| Senjafuda |

| Amulets sold at shrines for luck and protection |

| Omamori |

| Wooden plaques representing prayers and wishes |

| Ema |

| Paper fortunes received by making a small offering |

| O-mikuji |

| Stamps collected at shrines |

| Shuin |

Senjafuda (千社札, lit. 'thousand-shrine tags') are votive slips, stickers or placards posted on the gates or buildings of Shinto shrines and Buddhist temples in Japan. Unlike ofuda, which bear the name of the shrine, senjafuda bear the name of the worshipper, and can be purchased pre-printed with common names at temples and shrines throughout Japan, as well as at stationery stores and video game centres. Senjafuda were originally made from wooden slats, but have been made of paper since the Edo period.

A single senjafuda measures 1.6 sun (58 mm (2.3 in)) in width and 4.8 sun (173 mm (6.8 in)) in height. This gives the senjafuda a ratio of 1:3. A frame is drawn inside this space which contains the lettering or pictures. In 1887, a measurement for this frame was also established as 48 mm (1.9 in) wide and 144 mm (5.7 in) tall.

Ordinarily, the designs were used to commemorate a visit to a temple or shrine and printed with simple monochromatic schemes, but eventually aesthetic sense gave way to colorful variations and designs. In the pleasure quarters of Kyoto, colorful designs were employed on senjafuda and used in place of traditional business cards. This variation is called hana-meishi which roughly translated to "flower business card." Today, the "business card" use of senjafuda is the most common.

Senjafuda were primarily printed with Edomoji, or Edo-period lettering styles, and pressed with the same traditional wooden boards used to produce ukiyo-e prints. Stickers on shrines are often pasted in very obvious, easily seen locations, but a variation on this practice is to purposely obscure the location of the senjafuda in order to protect it from exposure to wind and rain and thus prolong its presence.

History

Senjafuda were first produced in the Heian period (794–1185) when shrine worshipers made pilgrimages to visits to many shrines and worship the Buddhist goddess of mercy, Kannon. They were not originally made of paper, they were first made from wooden slats that were hung from the gates of Kannon temples by nails made of bamboo. The slats were carved out with the visitors' name, area of origin and often included a prayer for a good life and afterlife.

There are two styles of senjafuda: the older style, daimei nosatsu, and the newer style, kokan nosatsu. Daimei nosatsu are basic black ink on white paper. The ink used is so strong that after the printed senjafuda are placed on the shrine or temple gate, years later when the paper is peeled away, the ink remains. Therefore, many shrine kannushi or shinshoku do not like the use of senjafuda, as well as more modern practices, where younger senjafuda practitioners do not pray or buy a stamp from the shrine before applying their senjafuda.

The later style of senjafuda are called kokan nosatsu and originated in the Edo period (1603–1868). During the beginning of the Edo period, shrine pilgrimages gained popularity, beginning the tradition known as senjamairi, meaning "a thousand shrine visits for good luck". Kokan nosatsu senjafuda are a lot more colorful than saimei nosatsu, and have rich patterns and designs, being used more as novelty items and more like trading cards or the business cards of today. Like many things during the Edo period, kokan nosatsu senjafuda were regulated, with the number of colours on a person's senjafuda limited to their class and place in society.

Because of this, collectors who enjoyed the many designs and colors of senjafuda began meeting to exchange them with one another;[1] first, the meetings took place at private homes, and then later were arranged for public places like restaurants and expensive tea houses. According to Kiritani's Vanishing Japan, the oldest surviving invitation card to a senjafuda meeting dates back to 1799.[2] Due to the growing popularity of senjafuda meetings, the government enforced a law forbidding their trading, which did not stop the meetings from taking place. Senjafuda meetings continue to this day, with collectors and aficionados alike meeting to share and trade their own designs as well as admire others.

US collector and Japanese anthropologist Frederick Starr was a turn-of-the-century collector and avid participant in senjafuda or nōsatsu-kai (votive slip exchange clubs), so much so that he was given the name "Dr. Ofuda". He collected tens of thousands of slips, and a fellow collector and popular art enthusiast, Gertrude Bass Warner, purchased much of his collection. It currently resides at the University of Oregon Knight Library Special Collections & University Archives, part of the Gertrude Bass Warner Collection, and examples are viewable online at UO Oregon Digital.[3][4]

Construction

Senjafuda used to be made from rice paper with ink called sumi, and were pasted on with a starchy rice paste. The pilgrims used to carry walking staffs for their long journeys, which doubled as an applicator for senjafuda. The paste was applied with something called meotobake – two brushes about 30 degrees apart, with a clip on the other side of the brushes, allowing senjafuda to be pasted in out of reach areas, leaving others to wonder exactly how they got up there.

In the present day, senjafuda are made from printed paper, and are rarely made traditionally through wood block printing. Wooden slat senjafuda, however, are still produced, and are worn as a necklace or used for key chain and cell phone ornaments. The ones made from paper are pre-printed with common names; machines are also available that can produce custom senjafuda with adhesive backings.

Famous figures

Some famous producers of senjafuda are Hiroshige, Eisen, Kunisada, Kuniyoshi. They mainly produced senjafuda, due to the expensive of the ukiyo-e printing process.

Senrei Sekioka was one of the foremost Japanese experts of senjafuda history; Iseman and Frederick Starr were also important members of the nosatsu-kai during the Meiji and Taishō eras.

Modern-day senjafuda

Senjafuda are also sold as stickers which do not require separate paste. As stickers, they are also placed in books and on personal items for identification and decoration. A common criticism of the sticker version of senjafuda is that they are more difficult to peel off than their original pasted ancestors, and thus can disfigure the underlying buildings when removed.

Gallery

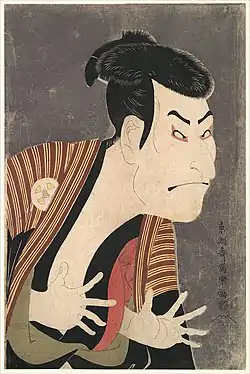

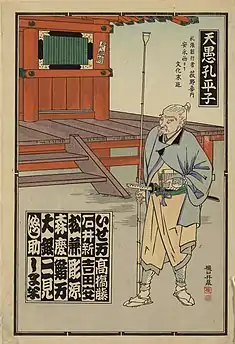

Nōsatsu, Shōki the Demon Queller

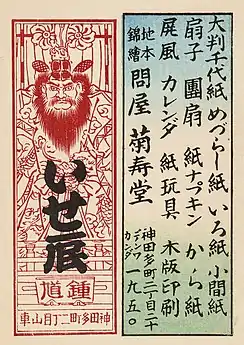

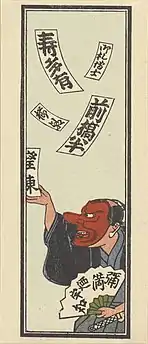

Nōsatsu, Shōki the Demon Queller Masked senjafuda collector tossing slips into the air

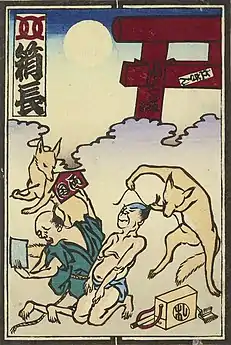

Masked senjafuda collector tossing slips into the air Fox hairdressers

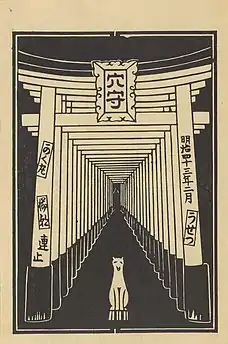

Fox hairdressers A stone fox statue in front of a series of shrine gates at Anamori Inari, Tokyo

A stone fox statue in front of a series of shrine gates at Anamori Inari, Tokyo Tengu Kōhei with a box for his senjafuda and pole-mounted brushes used for pasting

Tengu Kōhei with a box for his senjafuda and pole-mounted brushes used for pasting

See also

Notes

- ↑ "The world of senjafuda". Mellon Projects. Retrieved 24 November 2022.

- ↑ Kiritani, Elizabeth Vanishing Japan

- ↑ McDowell, Kevin. "Gertrude Bass Warner Collection of Japanese Shrine and Temple Votive Slips (nōsatsu)". Oregon Digital. University of Oregon. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

- ↑ McDowell, Kevin. "Rare Collection: Nōsatsu Japanese Shrine and Temple Votive Slips". Upbound UO Blog. Special Collections & University Archives, University of Oregon. Retrieved 3 May 2017.

References

- Gordenker, Alice, "So, What the Heck is That? Shrine tags", Japan Times, 18 November 2010, p. 13.

External links

Media related to Senjafuda at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Senjafuda at Wikimedia Commons- World of Senjafuda University of Oregon

- Gallery of senjafuda Christenson Collection of Miniature Japanese Woodblock Prints