The Serapeum of Alexandria in the Ptolemaic Kingdom was an ancient Greek temple built by Ptolemy III Euergetes (reigned 246–222 BC) and dedicated to Serapis, who was made the protector of Alexandria, Egypt. There are also signs of Harpocrates. It has been referred to as the daughter of the Library of Alexandria. The site has been heavily plundered.[1]

History

The site is located on a rocky plateau, overlooking land and sea.[1] By all detailed accounts, the Serapeum was the largest and most magnificent of all temples in the Greek quarter of Alexandria.

Besides the image of the god, the temple precinct housed an offshoot collection of the Library of Alexandria.[2] The geographer Strabo tells that this stood in the west of the city.

Nothing now remains above ground, except the enormous Pompey's Pillar. According to Rowe and Rees 1956, accounts of Serapeum's still standing buildings they saw there have been left by Aphthonius, the Greek rhetorician of Antioch "who visited it about A.D. 315", and Rufinus, "a Christian who assisted at the destruction of [it] during the end of the fourth century"; the Pillar marks the "Acropolis" of the Serapeum in the account by Aphthonius, that is, "the upper part of the great Serapeum area".[1]

Closure and destruction

The Serapeum of Alexandria was closed in July of 325 AD, likely on the orders of the Christian emperor Constantine. Emperor Theodosius I (379–395) gradually made pagan feasts into workdays, banned public sacrifices, and closed pagan temples. The decree promulgated in 391 declared that "no one is to go to the sanctuaries, [or] walk through the temples", which resulted in the abandonment of many temples throughout the Empire. This set the stage for riots in Alexandria in 391 (although the date is debated). According to Wace,[1]

The Serapeum was the last stronghold of the pagans who fortified themselves in the temple and its enclosure. The sanctuary was stormed by the Christians. The pagans were driven out, the temple was sacked, and its contents were destroyed.

The Serapeum was destroyed by Roman soldiers in 391[3][4] and not rebuilt. After the destruction, a monastery was established, a church was built for St. John the Baptist, known as Angelium or Evangelium. However, the church fell to ruins around 600 AD, restored by Pope Isaac of Alexandria (681–684 AD), and finally destroyed in the 10th century. In the 20th century, a Muslim cemetery, Bāb Sidra, was located at the site.[1]

The destruction of the Serapeum was but the most spectacular of such conflicts, according to Peter Brown.[5] Several other ancient, and modern authors, instead, have interpreted the destruction of the Serapeum in Alexandria as representative of the triumph of Christianity and an example of the attitude of the Christians towards pagans. However, Brown frames it against a long-term backdrop of frequent mob violence in the city, where the Greek and Jewish quarters had fought during four hundred years, since the 1st century BC.[6] Also, Eusebius mentions street-fighting in Alexandria between Christians and non-Christians, occurring as early as 249. There is evidence that non-Christians had taken part in citywide struggles both for and against Athanasius of Alexandria in 341 and 356. Similar accounts are found in the writings of Socrates of Constantinople. R. McMullan further reports that, in 363 (almost 30 years earlier), George of Cappadocia was killed for his repeated acts of pointed outrage, insult, and pillage of the most sacred treasures of the city.[7]

Accounts of the events

Several accounts for the context of the destruction of the Serapeum exist. According to church historians Sozomen and Rufinus of Aquileia, Bishop Theophilus of Alexandria obtained legal authority over one such temple of Dionysus, which he intended to convert into a church. During the renovations, the objects of pagan mystery still held within, especially the cultic phalli of Dionysus, were removed and exhibited in a procession of exposure, offense, and ridicule by the Patriarch; this incited crowds of pagans to seek revenge. They killed and wounded many Christians before seizing the Serapeum, still the most imposing of the city's remaining sanctuaries, and barricading themselves inside, taking captured Christians with them. These sources report that the captives were forced to offer sacrifices and that those who refused were tortured (their shins broken) and ultimately cast into caves that had been built for blood sacrifices. The pagans also plundered the Serapeum.[8]

A decree was issued by Theodosius offering the offending pagans pardon and calling for the destruction of all pagan images, suggesting that these were at the origin of the commotion. Consequently, the Serapeum was either destroyed, or (as per Sozomen) converted into a Christian temple, as were the buildings dedicated to the Egyptian god Canopus.[8]

About this period, the bishop of Alexandria, to whom the temple of Dionysus had, at his own request, been granted by the emperor, converted the edifice into a church. The statues were removed, the adyta (hidden statues) were exposed; and, in order to cast contumely on the pagan mysteries, he made a procession for the display of these objects; the phalli (ritual symbols of Dionysus), and whatever other object had been concealed in the adyta which really was, or seemed to be, ridiculous, he made a public exhibition of. The pagans, amazed at so unexpected an exposure, could not suffer it in silence, but conspired together to attack the Christians. They killed many of the Christians, wounded others, and seized the Serapion, a temple which was conspicuous for beauty and vastness and which was seated on an eminence. This they converted into a temporary citadel; and hither they conveyed many of the Christians, put them to the torture, and compelled them to offer sacrifice. Those who refused compliance were crucified, had both legs broken, or were put to death in some cruel manner. When the sedition had prevailed for some time, the rulers came and urged the people to remember the laws, to lay down their arms, and to give up the Serapion. There came then Romanus, the general of the military legions in Egypt; and Evagrius was the prefect of Alexandria. As their efforts, however, to reduce the people to submission were utterly in vain, they made known what had transpired to the emperor. Those who had shut themselves up in the Serapion prepared a more spirited resistance, from fear of the punishment that they knew would await their audacious proceedings, and they were further instigated to revolt by the inflammatory discourses of a man named Olympius, attired in the garments of a philosopher, who told them that they ought to die rather than neglect the gods of their fathers. Perceiving that they were greatly dispirited by the destruction of the idolatrous statues, he assured them that such a circumstance did not warrant their renouncing their religion; for that the statues were composed of corruptible materials, and were mere pictures, and therefore would disappear; whereas, the powers which had dwelt within them, had flown to heaven. By such representations as these, he retained the multitude with him in the Serapion. When the emperor was informed of these occurrences, he declared that the Christians who had been slain were blessed, inasmuch as they had been admitted to the honor of martyrdom, and had suffered in defense of the faith. He offered free pardon to those who had slain them, hoping that by this act of clemency they would be the more readily induced to embrace Christianity; and he commanded the demolition of the temples in Alexandria which had been the cause of the popular sedition. It is said that, when this imperial edict was read in public, the Christians uttered loud shouts of joy, because the emperor laid the odium of what had occurred upon the pagans. The people who were guarding the Serapion were so terrified at hearing these shouts, that they took to flight, and the Christians immediately obtained possession of the spot, which they have retained ever since. I have been informed that, on the night preceding this occurrence, Olympius heard the voice of one singing hallelujah in the Serapion. The doors were shut and everything was still; and as he could see no one, but could only hear the voice of the singer, he at once understood what the sign signified; and unknown to any one he quitted the Serapion and embarked for Italy. It is said that when the temple was being demolished, some stones were found, on which were hieroglyphic characters in the form of a cross, which on being submitted to the inspection of the learned, were interpreted as signifying the life to come. These characters led to the conversion of several of the pagans, as did likewise other inscriptions found in the same place, and which contained predictions of the destruction of the temple. It was thus that the Serapion was taken, and, a little while after, converted into a church; it received the name of the Emperor Arcadius.

(Sozomen, Historia Ecclesiastica, 7: 15)One of the soldiers, better protected by faith than by his weapon, grabs a double-edged axe, steadies himself and, with all his might, hits the jaw of the old statue. Hitting the worm-eaten wood, blackened by the sacrificial smoke, many times again, he brings it down piece by piece, and each is carried to the fire that someone else has already started, where the dry wood vanishes in flames. The head goes down, then the feet are hacked, and finally the god's limbs are ripped from the torso with ropes. And so it happens that, a piece at a time, the senile buffoon is burned right in front of its adorer, Alexandria. The torso, which had remained unscathed, was burned in the amphitheatre, in a final act of contumely. [...] A brick at a time, the building is taken apart by the righteous (sic) in the name of our Lord God: the columns are broken, the walls knocked down. The gold, the fabrics and precious marbles are removed from the impious stones imbued with the devil. [...] The temple, its priests and the wicked sinners are now vanquished and relegated to the flames of hell, as the vain superstition (paganism) and the ancient demon Serapis are finally destroyed.

- Tyrannius Rufinus, Historia ecclesiastica, 2: 23An alternate account of the incident is found in Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists by Eunapius, the pagan historian of later Neoplatonism.[9] Here, an unprovoked Christian mob successfully used military-like tactics to destroy the Serapeum and steal anything that may have survived the attack. According to Eunapius, the remains of criminals and slaves, who had been occupying the Serapeum at the time of the attack, were appropriated by Christians, placed in (surviving) pagan temples, and venerated as martyrs.[10][11]

But Antonius was worthy of his parents, for he settled at the Canobic mouth of the Nile and devoted himself wholly to the religious rites of that place, and strove with all his powers to fulfil his mother's prophecy. To him resorted all the youth whose souls were sane and sound, and who hungered for philosophy, and the temple was filled with young men acting as priests. Though he himself still appeared to be human and he associated with human beings, he foretold to all his followers that after his death the temple would cease to be, and even the great and holy temples of Serapis would pass into formless darkness and be transformed, and that a fabulous and unseemly gloom would hold sway over the fairest things on earth. To all these prophecies time bore witness, and in the end his prediction gained the force of an oracle. [...] An exception must be made of one of her sons; his name was Antoninus, and I mentioned him just now; he crossed to Alexandria, and then so greatly admired and preferred the mouth of the Nile at Canobus, that he wholly dedicated and applied himself to the worship of the gods there, and to their secret rites. He made rapid progress towards affinity with the divine, despised his body, freed himself from its pleasures, and embraced a wisdom that was hidden from the crowd. On this matter I may well speak at greater length. He displayed no tendency to theurgy and that which is at variance with sensible appearances, perhaps because he kept a wary eye on the imperial views and policy which were opposed to these practices. But all admired his fortitude and his unswerving and inflexible character, and those who were then pursuing their studies at Alexandria used to go down to him to the seashore. For, on account of its temple of Serapis, Alexandria was a world in itself, a world consecrated by religion: at any rate those who resorted to it from all parts were a multitude equal in number to its own citizens, and these, after they had worshipped the god, used to hasten to Antoninus--some, who were in haste, by land, while others were content with boats that plied on the river, gliding in a leisurely way to their studies. [...] Now, not long after, an unmistakable sign was given that there was in him some diviner element. For no sooner had he left the world of men than the cult of the temples in Alexandria and at the shrine of Serapis was scattered to the winds, and not only the ceremonies of the cult but the buildings as well, and everything happened as in the myths of the poets when the Giants gained the upper hand. The temples at Canobus also suffered the same fate in the reign of Theodosius, when Theophilus presided over the abominable ones like a sort of Eurymedon who ruled over the proud Giants, and Evagrius was prefect of the city, and Romanus in command of the legions in Egypt. For these men, girding themselves in their wrath against our sacred places as though against stones and stone-masons, made a raid on the temples, and though they could not allege even a rumour of war to justify them, they demolished the temple of Serapis and made war against the temple offerings, whereby they won a victory without meeting a foe or fighting a battle. In this fashion they fought so strenuously against the statues and votive offerings that they not only conquered but stole them as well, and their only military tactics were to ensure that the thief should escape detection. Only the floor of the temple of Serapis they did not take, simply because of the weight of the stones which were not easy to move from their place. Then these warlike and honourable men, after they had thrown everything into confusion and disorder and had thrust out hands, unstained indeed by blood but not pure from greed, boasted that they had overcome the gods, and reckoned their sacrilege and impiety a thing to glory in. Next, into the sacred places they imported monks, as they called them, who were men in appearance but led the lives of swine, and openly did and allowed countless unspeakable crimes. But this they accounted piety, to show contempt for things divine. For in those days every man who wore a black robe and consented to behave in unseemly fashion in public, possessed the power of a tyrant, to such a pitch of virtue had the human race advanced! [...T]hey collected the bones and skulls of criminals who had been put to death for numerous crimes, men whom the law courts of the city had condemned to punishment, made them out to be gods, haunted their sepulchres, and thought that they became better by defiling themselves at their graves. "Martyrs" the dead men were called, and "ministers" of a sort, and "ambassadors" from the gods to carry men's prayers,--these slaves in vilest servitude, who had been consumed by stripes and carried on their phantom forms the scars of their villainy. However these are the gods that earth produces! This, then, greatly increased the reputation of Antoninus also for foresight, in that he had foretold to all that the temples would become tombs. Likewise the famous Iamblichus, as I have handed down in my account of his life, when a certain Egyptian invoked Apollo, and to the great amazement of those who saw the vision, Apollo came: "My friends," said he, "cease to wonder; this is only the ghost of a gladiator." So great a difference does it make whether one beholds a thing with the intelligence or with the deceitful eyes of the flesh. But Iamblichus saw through marvels that were present, whereas Antoninus foresaw future events. This fact of itself argues his superior powers. His end came painlessly, when he had attained to a ripe old age free from sickness. And to all intelligent men the end of the temples which he had prognosticated was painful indeed.

- Eunapius, Lives of Philosophers and Sophists, 421-427Excavations

.jpg.webp)

Architecture has been traced to an early Ptolemaic and a second Roman period.[1] The excavations at the site of the column of Diocletian in 1944 yielded the foundation deposits of the Serapeion. These are two sets of ten plaques, one each of gold, silver, bronze, Egyptian faience, sun-dried Nile mud, and five of opaque glass.[12] The inscription that Ptolemy III Euergetes built the Serapeion, in Greek and Egyptian, marks all plaques; evidence suggests that Parmeniskos (Parmenion) was assigned as architect.[13]

The foundation deposits of a temple dedicated to Harpocrates from the reign of Ptolemy IV Philopator were also found within the enclosure walls.[14]

Signs point to a first destruction during the Kitos War in 116 AD. It has been suggested it was then rebuilt under Hadrian.[1] This is supported with the 1895 find of a black diorite statue, representing Serapis in his Apis bull incarnation with the sun disk between his horns; an inscription dates it to the reign of Hadrian (117–138).

It has also been suggested that there was worship of the goddess of health, marriage, and wisdom Isis.[1] Subterranean galleries beneath the temple were most probably the site of the mysteries of Serapis. Granite columns suggest a Roman rebuilding and widening of the Alexandrine Serapeum in AD 181–217. Excavations recovered 58 bronze coins, and 3 silver coins, with dates up to 211.[15] The torso of a marble statue of Mithras was found in 1905/6.[1]

Statues

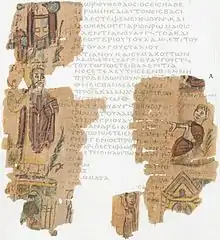

According to fragments, there were statues of the twelve gods. Mimaut mentioned in the 19th century, nine standing statues holding rolls, which would coincident with the nine goddesses of the arts, reportedly present at the Library of Alexandria.[16] Eleven statues were found at Saqqara. A review of "Les Statues Ptolémaïques du Sarapieion de Memphis" noted they were probably sculpted in the 3rd century with limestone and stucco, some standing others sitting. Rowe and Rees 1956 suggested that both scenes in the Serapeum of Alexandria and Saqqara, share a similar theme, such as with Plato's Academy mosaic, with Saqqara figures attributed to: "(1) Pindare, (2) Démétrios de Phalère, (3) x (?), (4) Orphée (?) aux oiseaux, (5) Hésiode, (6) Homère, (7) x (?), (8) Protagoras, (9) Thalès, (10) Héraclite, (11) Platon, (12) Aristote (?)."[1][17]

Serapeum, quod licet minuatur exilitate verborum, atriis tamen columnariis amplissimis et spirantibus signorum figmentis et reliqua operum multitudine ita est exornatum, ut post Capitolium, quo se venerabilis Roma in aeternum attollit, nihil orbis terrarum ambitiosius cernat.

Ammianus Marcellinus, Res Gestae, XXII, 16

The Serapeum, splendid to a point that words would only diminish its beauty, has such spacious rooms flanked by columns, filled with such life-like statues and a multitude of other works of such art, that nothing, except the Capitolium, which attests to Rome's venerable eternity, can be considered as ambitious in the whole world.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Rowe, Alan; Rees, B. R. (March 1957). "A contribution to the archaeology of the Western Desert: IV. With one plate". Bulletin of the John Rylands Library. 39 (2): 485–520. doi:10.7227/bjrl.39.2.9. ISSN 2054-9326.

- ↑ Sabottka, M. (1986). Das Serapeum in Alexandria. Paper presented at the Koldeway-Gesellschaft, Bericht über die 33. Tagung für Ausgrabungswissenschaft und Bauforschung 30. Mai-30. Juni 1984. Sabottka, M. (1989). Das Serapeum in Alexandria. Untersuchungen zur Architektur und Baugeschichte des Heiligtums von der frühen ptolemäischen Zeit bis zur Zerstörung 391 n. Chr., Dissertation, University of Berlin.

- ↑ Hahn: Gewalt und religiöser Konflikt. p. 82.

- ↑ See Hebblewhite, M. (2020) Theodosius and the Limits of Empire 120ff for a useful overview of the episode.

- ↑ The Rise of Western Christendom (2003): 73–74.

- ↑ Kreich, Chapter 4 Archived 2010-05-31 at the Wayback Machine, Michael Routery, 1997.

- ↑ Ramsay McMullan, Christianizing the Roman Empire A.D. 100–400 (Yale University Press) 1984: 90.

- 1 2 MacMullen (1984)

- ↑ Lives of the Philosophers and Sophists (LCL vol. 134, pp. 416–425)

- ↑ Cox Miller, Patricia (2000). "10. Strategies of Representation in Collective Biography: Constructing the Subject as Holy". In Hägg, Tomas; Rousseau, Philip (eds.). Greek Biography and Panegyric in Late Antiquity. With the assistance of Christian Høgel. University of California Press. pp. 222–223. ISBN 9780520223882.

- ↑ (Turcan, 1996)

- ↑ Kessler, D. (2000). Das hellenistische Serapeum in Alexandria und Ägypten. Paper presented at the Ägypten und der östliche Mittelmeerraum im 1. Jahrtausend v. Chr. conference, Berlin.

- ↑ McKenzie, J. (2007). The Architecture of Alexandria and Egypt, C. 300 B.C. to A.D. 700: Yale University Press.

- ↑ McKenzie, J. S., Gibson, S., & Reyes, A. T. (2008). Reconstructing the Serapeum in Alexandria from the Archaeological Evidence.

- ↑ Judith McKenzie, "Glimpsing Alexandria from archaeological evidence"; Journal of Roman Archaeology Vol. 16 (2003), pp. 50–56. "The Roman version of the Serapeum, which was larger, was built between 181 and 217. Concrete foundations and parts of granite columns survive from this phase. The concrete foundations enclose the foundations of the ashlar walls of the Ptolemaic temple, following the Egyptian custom. [...] Foundation deposits of coins were found embedded in the corners of the pool near the E entrance, 'the floor of the pool being of exactly the same material as the foundations of the Roman temple itself'. The latest coin is dated to 211 and provides a terminus post quem the pool and an indication of the date of construction of the Roman temple."

- ↑ Murray, S. A., (2009). The library: An illustrated history. New York: Skyhorse Publishing, p. 17

- ↑ Ph. Lauer; Ch. Picard (1957). "Reviewed Work: Les Statues Ptolémaïques du Sarapieion de Memphis". Archaeological Institute of America. doi:10.2307/500375. JSTOR 500375.

External links

Media related to Serapeum of Alexandria at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Serapeum of Alexandria at Wikimedia Commons- Rufinus – "The Destruction of the Serapeum A.D. 391"

- Richard Stillwell, ed. Princeton Encyclopedia of Classical Sites, 1976: "Alexandria, Egypt: Serapeion"