| Shuri Castle 首里城 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Naha, Okinawa | |||||

Seiden (main hall) of Shuri Castle in 2016 | |||||

| Coordinates | 26°13′1.31″N 127°43′10.11″E / 26.2170306°N 127.7194750°E | ||||

| Type | Gusuku | ||||

| Site information | |||||

| Open to the public | Partly (Main castle closed due to fire in 2019) | ||||

| Condition | Four main structures irreparably destroyed, surrounding structures intact.[1] Reconstruction work underway as of February 2020.[2] | ||||

| Site history | |||||

| Built | 14th century, first rebuild 1958–1992, second rebuild 2020-present | ||||

| In use | 14th century – 1945 | ||||

| Materials | Ryukyuan limestone, wood | ||||

| Demolished | 2019, destroyed by fire; 4 times previously (1453, 1660, 1709, 1945) | ||||

| Battles/wars | Invasion of Ryukyu (1609) World War II

| ||||

| Garrison information | |||||

| Occupants | Kings of Chūzan and Ryukyu Kingdom Imperial Japanese Army | ||||

| Japanese name | |||||

| Kanji | 首里城 | ||||

| Hiragana | しゅりじょう | ||||

| Katakana | シュリジョウ | ||||

| |||||

| Criteria | Cultural: ii, iii, vi | ||||

| Reference | 972 | ||||

| Inscription | 2000 (24th Session) | ||||

Shuri Castle (首里城, Shuri-jō, Okinawan: Sui Ugusuku[3]) is a Ryukyuan gusuku castle in Shuri, Okinawa Prefecture, Japan. Between 1429 and 1879, it was the palace of the Ryukyu Kingdom, before becoming largely neglected. In 1945, during the Battle of Okinawa, it was almost completely destroyed. After the war, the castle was re-purposed as a university campus. Beginning in 1992, the central citadel and walls were largely reconstructed on the original site based on historical records, photographs, and memory. In 2000, Shuri Castle was designated as a World Heritage Site, as a part of the Gusuku Sites and Related Properties of the Kingdom of Ryukyu. On the morning of 31 October 2019, the main courtyard structures of the castle were again destroyed in a fire.[4]

History

The date of construction is uncertain, but it was clearly in use as a castle during the Sanzan period (1322–1429). It is thought that it was probably built during the Gusuku period, like many other castles of Okinawa. When King Shō Hashi unified the three principalities of Okinawa and established the Ryukyu Kingdom, he used Shuri as a residence.[5] At the same time, Shuri flourished as the capital and continued to do so during the Second Shō dynasty.

For 450 years from 1429, it was the royal court and administrative center of the Ryukyu Kingdom. It was the focal point of foreign trade, as well as the political, economic, and cultural heart of the Ryukyu Islands. According to records, the castle burned down several times, and rebuilt each time. During the reign of Shō Nei, samurai forces from the Japanese feudal domain of Satsuma seized Shuri on 6 May 1609.[6] The Japanese withdrew soon afterwards, returning Shō Nei to his throne two years later, and the castle and city to the Ryukyuans, though the kingdom was now a vassal state under Satsuma's suzerainty and would remain so for roughly 250 years.

Decline

In the 1850s, Commodore Matthew C. Perry twice forced his way into Shuri Castle, but was denied an audience with the king both times.[7] In 1879, the kingdom was annexed by the Empire of Japan and the last king, Shō Tai, was compelled to move to Tokyo, and in 1884, he was “elevated” to the rank of marquess in the Japanese aristocracy. Subsequently, the castle was used as a barracks by the Imperial Japanese Army. The Japanese garrison withdrew in 1896,[8] but not before having created a series of tunnels and caverns below it.

In 1908, Shuri City bought the castle from the Japanese government; however, it did not have funding to renovate it. In 1923, thanks to Japanese architect Ito Chuta, Seiden survived demolition after being re-designated a prefectural Shinto shrine known as Okinawa Shrine. In 1925, it was designated as a national treasure. Despite its decline, historian George H. Kerr described the castle as "one of the most magnificent castle sites to be found anywhere in the world, for it commands the countryside below for miles around and looks toward distant sea horizons on every side."[9]

World War II

During World War II, the Imperial Japanese Army had set up its headquarters in the castle underground, and by early 1945 had established complex lines of defense and communications in the regions around Shuri, and across the southern part of the island as a whole. The Japanese defenses, centered on Shuri Castle, held off the massive American assault from 1 April through the month of May 1945. Beginning on 25 May, and as the final part of the Okinawa campaign, the American battleship Mississippi shelled it for three days[10][11] and by 27 May it was ablaze.[12] The Japanese retreated during the night, abandoning Shuri, while the US forces continued to pursue them south. US Marine and Army units secured the castle against little resistance.[11][13] On 29 May, Maj. Gen. Pedro del Valle—commanding the 1st Marine Division—ordered Captain Julian D Dusenbury of Company A, 1st Battalion, 5th Marines to capture the castle, which represented both strategic and psychological blows for the Japanese and was a milestone in the campaign.[14]

Post-war

After the war, the University of the Ryukyus was established in 1950 on the castle site, where it remained until 1975. In 1958, Shureimon was reconstructed and, starting from 1992, the 20th anniversary of reversion, the main buildings and surrounding walls of the central castle were reconstructed. At present, the entire area around the castle has been established as "Shuri Castle Park". In 2000, along with other gusuku and related sites, it was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site. However, only remnants such as stone walls and building foundations extant before 1950 are officially designated as World Heritage. In addition, 2000 saw the Shureimon gate at Shuri Castle featured on the new 2000 yen note, which entered circulation to commemorate the new millennium and the 26th G8 summit, which was held in Okinawa.

2019 fire

In the morning of 31 October 2019, a large fire broke out and burned down the Seiden, the main hall, and also the Hokuden and Nanden, adjacent buildings to the north and south.[4] A security alarm went off around 2:30 a.m., and a call to emergency services was placed around 10 minutes later. The Seiden, Hokuden, Nanden and Bandokoro were completely destroyed.[15] According to domestic news sources, "Six castle buildings occupying some 4,200 square metres (45,000 sq ft) in total were gutted."[16][17] The fire was put out around 1:30 p.m.[18]

Okinawa Police later told domestic broadcaster NHK that a security guard who checked on the alarm found that the main entrance doors to the Seiden were closed. When the guard unlocked the shutter and went inside, the interior was already filled with smoke.[19] After police initially ruled out arson,[20] authorities said that the fire was likely caused by an electrical fault after a burned electrical distribution board was found in the northeast side of where the Seiden had stood.[21] Police investigations later revealed that the lighting panel had no signs of short circuiting, though a surveillance camera did capture flashing light in the Seiden main hall shortly before and after the fire.[22]

The fire was the fifth time that Shuri Castle has been destroyed following previous incidents in 1453, 1660, 1709 and 1945.[23] Okinawa Governor Denny Tamaki said after the fire that Shuri Castle is "a symbol of the Ryukyu Kingdom, an expression of its history and culture", and has vowed to rebuild it.[24] Japan's Chief Cabinet Secretary Yoshihide Suga said that Shuri Castle is "an extremely important symbol of Okinawa".[19] The Japanese Government is considering supplemental appropriations to support restoration work.[19] UNESCO also said it would be ready to assist with Shuri Castle's reconstruction.[25] A crowdfunding campaign set up by Naha City officials for the rebuilding of Shuri Castle had received over $3.2 million in donations as of 6 November 2019.[26]

As of 10 February 2020, rebuilding efforts to restore the destroyed sections of Shuri Castle were underway.[27] In May 2021, a scale replica of the castle measuring one twenty fifth of the size of the actual structure was recreated at the Tobu World Square theme park in Kinugawa Onsen.[28]

Construction

Unlike Japanese castles, Shuri Castle was greatly influenced by Chinese architecture, with functional and decorative elements similar to that seen primarily in the Forbidden City. The gates and various buildings were painted in red with lacquer, walls and eaves colorfully decorated, and roof tiles made of Goryeo and later red Ryukyuan tiles, and the decoration of each part heavily using the king's dragon. Given that the Nanden and Bandokoro were both used for reception and entertainment of the Satsuma clan, a Japanese style design was used here only.

Ryukyuan elements also dominate. Like other gusuku, the castle was built using Ryukyuan limestone, being surrounded by an outer shell which was built during the Second Shō dynasty from the second half of the 15th century to the first half of the 16th century. Similarly, Okushoin-en is the only surviving garden in a gusuku in the Ryukyu Islands, which made use of the limestone bedrock and arranged using local cycads.

The current renovation is designed with a focus on the castle's role as a cultural or administrative/political center, rather than one for military purposes. The buildings that had been restored as original wooden buildings (and subsequently destroyed in the 2019 fire) were only in the main citadel. The Seiden was rebuilt using wood from Taiwan and elsewhere after rituals blessing the removal of large trees from mountains in the Yanbaru region of Okinawa took place. Other buildings, such as the Nanden or Hokuden were only restored as facades, with interiors made using modern materials such as steel and concrete. Old walls remain in part, and were excavated and incorporated during the construction of the new castle wall, forming the only surviving external remains of the original castle.

Sites of interest

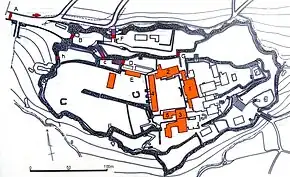

Due to its central role in Ryukyuan political and religious life, Shuri is composed of and surrounded by various sites of historical interest. The castle complex itself can be divided into three main zones, namely a central administrative area (including the Seidan and Ura), an eastern living and ceremonial space (behind the Seidan) called the Ouchibara (literally "inside field"), and a southwestern ceremonial area including the Kyo-no-uchi (literally "inside capital").

Buildings

All of the buildings located at Shurijo are modern reconstructions, the originals being lost in 1945.

- Bandokoro (番所) – located south of the Una, and paired with the Nanden, originally the main reception area, currently housing a museum. The two were built between 1621 and 1627.

- Hokuden 北御殿 (nishi nu udun) (北殿) – the "North Hall", located north of the Una, originally a judicial and administrative center where Sapposhi (Chinese envoys) were also received, currently housing a museum and gift-shop. Originally called the Nishi-no-udun or Giseiden, it was built around 1506–1521.

- Keizuza (系図座) – located east of the Shicha-nu-una, originally the government office responsible for the genealogy of noble families, currently housing a tearoom and stage for Ryukyuan dance shows.

- Kinju-tsumesho (近習詰所) – a work area for high-officials (such as the Kinju-gashira, Kinju-yaku, and Hisa), currently a passageway between the Nanden and Seiden.

- Kugani-udun (黄金御殿) – private area for the king, his wife, and mother, south of the Seiden. Originally dated to at least 1671, and rebuilt by 1715, it connected the Nanden to Oku-shoin. Inner rooms included the Suzuhiki and Ochane-zume.

- Nanden (fee nu udun) (南殿) – the "South Hall", formerly an entertainment area for Satsuma envoys, currently an exhibition space.

- Ni-kei-udun (二階御殿) – a sitting room for the king linked to the Seidan. Built in 1765, it was later extended south in 1874.

- Nyokan-kyoshitsu 城人御詰所 gushikunchu utsumesho (女官居室) – unknown function. Located north of the Kushino-una.

- Oku-shoin (奥書院) – rest house for the king, south of the Seiden, originally dated to at least 1715.

- Sasumoma (鎖之間) – anteroom located south of the Nanden for royal princes, and guest/official reception area.

- Seiden 百浦添御殿 mundashii udun (正殿) – the "Main Hall", also called the State Palace, was situated to the east of the Una, but facing west towards China, and contains the throne room and royal living and ceremonial areas. The western facade includes two 4.1 meter high Dai-Ryu Chu (Great Dragon Pillars), crafted of sandstone from Yonaguni Island, and symbols of the king. The left dragon is called Ungyou, and the right is Agyou, and these motifs are replicated throughout the building including the roof. Other decorative elements include botan (peony flowers), shishi (golden dragons), and zuiun (clouds). The Shichagui (first floor) was where the king personally conducted affairs of state and ceremonies. The Usasuka was the lower area in front of where the king sat, with the Hira-usasuka (side-areas) flanking either side. The second floor included the Ufugui, the area for the queen and her attendants, and the Usasuku, the upper main throne room of the king. Behind it are the Osenmikocha, chambers where the king would pray daily. According to historical records, the Seiden was burned down and rebuilt four times (most recently in 1992), and was also used as the prayer hall for a Shinto shrine between 1923-1945.

- Shoin (書院) – study and office of the king, south of the Nanden, where Chinese/Satsuma officials were entertained when visiting.

- Suimuikan (首里杜館) – cultural/exhibition center, gift shop, and restaurant area.

- Tomoya (供屋) – unknown function, but now housing the Bridge of Nations Bell replica.

- Yohokoriden (Yuufukui udun (世誇殿) – immediately east of the Seiden, it was the regular sleeping area for unmarried princesses, and the location of the ascension ceremony.

- Youmoutsuza (用物座) – paired building with the Keizuza, which dealt with the goods and materials used inside the castle.

- Yuinchi (寄満) – royal food preparation area, connected to the Kugani-udun, dated to at least 1715. Attendants included the Hocho (chef) and Agama (female servants).

Courtyard (~una)

- Kushino-una (後之御庭) – the living area immediately behind the Seiden, surrounded by the Nyokan-kyoshitsu and Yuinchi.

- Shicha-nu-una (下之御庭) – the lower area between the Houshinmon and Koufukumon.

- Una (御庭) - the central and primary reception and ceremonial area of the castle in front of the Seiden.

Gates (~mon)

- Bifukumon (美福門) – a gate leading south of the Kushino-una, leading to the Ouchibara. Called Akata-ujo prior to the construction of Keiseimon.

- Chūzanmon (中山門) – the first ceremonial gate to Shurijo, built around 1427 by King Shō Hashi, it was demolished in 1907.

- Hakuginmon (白銀門) – the easternmost gate leading to the Shinbyoden.

- Houshinmon (奉神門) – also known as Kimihokori-ujo, it is the main citadel entrance to the Una, currently the ticket check gate. Although the period of construction is unknown, the stone balustrades were completed in 1562.

- Kankaimon (歓会門) – built around 1477–1500 during the reign of King Shō Shin, the gate was burned down during the Battle of Okinawa in 1945 and restored in 1974. It is the first main gate to the castle. Kankai (歓会), which means "welcome", the gate was named to express welcome to the investiture envoys who visited Shuri as representatives of the Chinese Emperor.

- Keiseimon (継世門) – a southwest gate south of Bifukumon, also called Akata-ujo. Normally a side-gate, it was used by the Crown Prince when officially ascending the throne. The door was restored in 1998.

- Kobikimon (木曳門) – a trade gate usually blocked with stones, but opened for movement of building and wall repair materials.

- Koufukumon (広福門) – the entrance into the Shicha-nu-una, currently the ticket purchase gate. Historically, the eastern wing of the building housed Okumiza, the deputy's office to intervene in disputes between noble families. The west wing housed the Jishaza, the magistrate responsible for supervising the places of worship.

- Kyukeimon (久慶門) – the northern gate mostly used by women, also known as Hokoriujo hokori, meaning "Pleasant Pride". It was built during the reign of King Shō Shin.

- Roukokumon (漏刻門) – a gate housing a roukoku (water clock) in the turret, also called Kagoise-ujo. Visitors would dismount their horses or palanquins here.

- Shukujunmon (淑順門) – the citadel gate north of the Seiden, also called Onaka-ujo, leading to the Ouchibara.

- Shureimon (守礼門) – the second ceremonial gate built between 1527 and 1555, and now the main gate to the complex.

- Uekimon (右掖門) – leads directly to Kyukeimon. It was used as a service entrance to the Ouchibara.

- Zuisenmon (瑞泉門) – literally "splendid and auspicious spring gate", located near Ryuhi and probably built around 1470.

Shrines (~utaki) and temples (~ji)

- Benzaitendo (弁財天堂, Okinawan: Bizaitindoo) – a shrine built to house Housatsuzou-kyou (Buddhist scriptures) gifted by Sejo, the 7th Joseon king of Korea.

- Enkaku-ji (円覚寺, Okinawan: Ufutira) – a Buddhist temple for the royal family in the lower precincts north of the citadel, constructed in 1492.

- Kawarume-utaki (苅銘御嶽) – a small private shrine near the Okushoin.

- Kyo-no-uchi (京の内, Okinawan: chuu nu uchi) – a large open ritual area where prayers by the Kikoe-ōgimi (chifi-ufujin) (high-priestess) were made.

- Sonohyan-utaki (園比屋武御嶽, Okinawan: sunuhyan utaki) – a sacred stone "gate" to the left of Shureimon was erected in 1519, where the king offered prayers for order throughout the kingdom and safety at the outset of his travels.

- Suimui-utaki (首里森御嶽) – a walled worship space, supposedly "created by the gods", inside the Shicha-nu-una. It is the theme of many of the songs and prayers recorded in Omoro Sōshi (Okinawan: umuru sooshi), Ryukyu's oldest music collection.

Other features

- Agari-no-azana (東のアザナ) – the eastern lookout point of the innermost wall.

- Enganchi (円鑑池) – a moat created around Benzaitendo.

- Hojo-bashi (放生橋) – a stone bridge behind Enkaku-ji.

- Iri-no-azana (西のアザナ) – a modern lookout tower overlooking Naha.

- Nichiei-dai (日影台) – a sundial in front of Roukokumon and next to the Tomoya, which kept time in Shuri from around 1739 until 1879.

- Okushoin-en (奥書院園) – a private garden behind the Okushoin.

- Ouchibaru (御内原) – the residential area of the citadel to the east of the Seiden, forbidden to men except those of the royal family.

- Ryuhi (龍樋) – a natural spring in front of Zuisenmon, with a dragon headed spout.

- Ryutan (龍潭) – a man-made pond, built in 1427 and located north of Shureimon.

- Shikina-en (識名園) – built in 1799, the royal gardens and villa are a rare, historically valuable example of Ryukyuan landscape gardening.

- Shinbyoden (寝廟殿) – the easternmost area of the inner citadel where the body of a king was temporarily held.

- Tamaudun (玉陵) – the restored royal tombs of the Second Shō dynasty, located adjacent to Shurijo, where 17 kings, along with their queens and royal children, are entombed.

Ceremonies

Religious

Shurijo operated not only as a base of political and military control, it was also regarded as a central religious sanctuary of the Ryukyuan people. Formerly there were 10 utaki (shrines) within the castle and the large area on the south-western side of the citadel was occupied by a sanctuary called Kyo-no-uchi. This was a place where natural elements, such as trees and natural limestone rocks were utilized. Although Noro (priestesses) carried out a number of nature rituals (as also sometimes occurs in Shinto), the contents of the rituals and the layout of the inner part of the sacred areas remain unclear. After the war, limited religious observance continued on the site, mostly with the placement of incense sticks on places formerly considered sacred. However, restoration of the castle stopped general access to these sites, and for this reason, "Shuri Castle was resurrected, but it was destroyed as a place of worship".

Investiture

Contacts between the Ryukyu Islands and China began in 1372 and lasted five centuries until the establishment of Okinawa Prefecture in 1879. When a new king commenced, the Emperor of China sent officials to attend the investiture ceremony at the castle. Through this ceremony, the kingdom reiterated its ties with China, both politically, commercially, and culturally. This custom also granted the new monarch official international recognition within east Asia.

The Chinese delegation included about 500 people, including a Sapposhi (ambassador) and a representative, both appointed by senior officials of the emperor. The envoys departed from Beijing and proceeded by land to Fuzhou in Fujian Province, where they sailed to the Ryukyu Islands, sometimes via Kumejima, on Ukanshin ("Crown Ships").

Among the first tasks of the Chinese delegation was a Yusa (religious ceremony) in memory of the late king. Words of condolence from the emperor were spoken in Sōgen-ji in Naha, and (after 1799) envoys were then received in Shikina-en. Then the investiture ceremony took place in the Una, where two platforms were erected between the Nanden and Seiden, called Kettei, reserved for the envoys, and Sendokudai. The imperial official recited the formula for the appointment of the new king and bowed deeply.

Later, inside the castle, there was a "Feast of Investiture," followed by a "Mid-autumn Banquet", accompanied by songs and dances. This banquet was held on a temporary platform opposite the Hokuden, a platform on which the Imperial envoys stood. On the shore of Ryutan and in the castle, the "Choyo Banquet", during which a boat race and musical performances took place, was also held in the presence of the delegation. Two successive farewell banquets were then held opposite Hokuden, and finally a banquet at Tenshikan, where the king gave the Chinese delegation gold presents as an august sign for their return.

In popular culture

In the 2002 computer game, Deadly Dozen: Pacific Theater, the last mission takes place while assaulting Shurijo. In the 2008 video game, Call of Duty: World at War, the last American mission ("Breaking Point") also takes place in the castle, where US Marines make their final push to take Okinawa. In the game, main characters in the plot die alongside several US forces as the player proceeds upwards under mortar and small arms fire to Ura, the courtyard of the ruined castle, which was targeted by US airstrikes to soften Japanese forces entrenched there. Also the Call of Duty World at War multiplayer map ("Courtyard") takes place at Shuri Castle.

Gallery

Prewar Una and buildings before destruction

Prewar Una and buildings before destruction Shuri Castle

Shuri Castle Seiden - front facade

Seiden - front facade Usasuku - the upper royal throne room

Usasuku - the upper royal throne room Suimuikan

Suimuikan Shureimon

Shureimon Kankaimon

Kankaimon Zuisenmon

Zuisenmon Ryuhi

Ryuhi Suimi-utaki

Suimi-utaki Sasunoma

Sasunoma Kyo-no-uchi

Kyo-no-uchi Wall near Kyukeimon, with Ryutan in the distance

Wall near Kyukeimon, with Ryutan in the distance.jpg.webp) Benzaitendo, with Enganchi in the foreground.

Benzaitendo, with Enganchi in the foreground. 500 yen coin, issued to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa, with Shuri Castle depicted on the obverse side of the coin

500 yen coin, issued to commemorate the 20th anniversary of the reversion of Okinawa, with Shuri Castle depicted on the obverse side of the coin Shuri Castle's main gate and main hall's charred roof two days after the 2019 fire

Shuri Castle's main gate and main hall's charred roof two days after the 2019 fire

See also

References

- ↑ Tara John. "Fire breaks out in Japan's Shuri Castle". CNN. Retrieved Oct 31, 2019.

- ↑ "Shuri Castle Reconstruction Work Begins". nippon.com. 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2020-11-07.

- ↑ "スイグシク". 首里・那覇方言音声データベース (in Japanese). Archived from the original on 2020-08-07. Retrieved 2010-02-16.

- 1 2 "Shuri Castle, a symbol of Okinawa, destroyed in fire". The Japan Times Online. 2019-10-31. ISSN 0447-5763. Archived from the original on 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ↑ Okinawa Prefectural reserve cultural assets center (2016). "発見!首里城の食といのり". Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan. Retrieved 2016-09-02.

- ↑ Turnbull, Stephen (2009). The Samurai Capture a King: Okinawa 1609. Oxford: Osprey Publishing. pp. 58. ISBN 9781846034428.

- ↑ Kerr. pp. 315–317, 328.

- ↑ Kerr. p. 460.

- ↑ Kerr, George H. (2000). Okinawa: The History of an Island People (revised ed.). Boston: Tuttle Publishing. p. 50.

- ↑ Kerr, George. Okinawa: The History of an Island People. Revised Edition. Tokyo: Tuttle Publishing, 2000. p. 470.

- 1 2 "The Ordeals of Shuri Castle". Wonder-okinawa.jp. August 15, 1945. Archived from the original on July 4, 2009. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ↑ "The Ordeals of Shuri Castle". Archived from the original on 2009-07-04. Retrieved 2010-04-05.

- ↑ "The Final Campaign: Marines in the Victory on Okinawa (Assault on Shuri)". Nps.gov. Archived from the original on April 15, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2010.

- ↑ "Valor awards for Julian D. Dusenbury". valor.militarytimes.com. Retrieved 2016-06-22.

- ↑ "焼け落ちる正殿 未明に首里城で火災 消火活動続く". ANNnewsCH. 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 2021-12-21. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ↑ "Historic Okinawa castle gutted as predawn blaze rages". Mainichi Daily News. 2019-10-31. Archived from the original on 2019-10-31. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ↑ "Fire destroys Okinawa's Shuri Castle | NHK WORLD-JAPAN News". NHK WORLD. Retrieved 2019-10-31.

- ↑ "首里城の火災鎮火". Jiji.com (in Japanese). Jiji. 31 October 2019. Archived from the original on 1 November 2019. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- 1 2 3 "Entrance to Shurijo main hall shut at time of fire". www3.nhk.or.jp. NHK World-Japan. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ↑ "Police believe arson unlikely in Okinawa castle fire". english.kyodonews.net. Kyodo News. 2 November 2019. Retrieved 3 November 2019.

- ↑ "Electrical fault likely caused Shuri Castle fire". www3.nhk.or.jp. NHK World-Japan. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ "Electrical fault could have caused inferno at Okinawa's Shuri Castle, police say". The Japan Times. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 1 December 2020.

- ↑ "History of Shuri Castle" (PDF). oki-park.jp. Oki Park Official Site. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ↑ Ando, Ritsuko; Kim, Chang-Ran (31 October 2019). "Fire destroys Japan's World Heritage-listed Shuri Castle". reuters.com. Reuters. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- ↑ "UNESCO ready for Shurijo Castle reconstruction". www3.nhk.or.jp. NHK World-Japan. 1 November 2019. Retrieved 1 November 2019.

- ↑ "Shuri Castle rebuilding fund over $3 mil". www3.nhk.or.jp. NHK World-Japan. 6 November 2019. Retrieved 6 November 2019.

- ↑ "Shuri Castle Reconstruction Work Begins". nippon.com. 2020-02-10. Retrieved 2020-06-15.

- ↑ "Fire-hit Shuri Castle recreated in miniature form at theme park," Kyodo News, 3 May 2021, retrieved 26 July 2021

Further reading

- Benesch, Oleg and Ran Zwigenberg (2019). Japan's Castles: Citadels of Modernity in War and Peace. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 374. ISBN 9781108481946.

- De Lange, William (2021). An Encyclopedia of Japanese Castles. Groningen: Toyo Press. pp. 600 pages. ISBN 978-9492722300.

- Oleg Benesch, Ran Zwigenberg, Shuri Castle and Japanese Castles: A Controversial Heritage, The Asia-Pacific Journal. Japan Focus 17, 24, 3 (Decembre 2019, 15)

- Motoo, Hinago (1986). Japanese Castles. Tokyo: Kodansha. ISBN 0-87011-766-1.

External links

- Shuri Castle Park

- 首里城公園 空からみた首里城 (Shuri Castle Park as seen from the sky) YouTube

- Okinawa Prefectural Government | Shurijo

- Prefecture of Okinawa | Shuri-jo

- Comprehensive Database of Archaeological Site Reports in Japan, Nara National Research Institute for Cultural Properties Japanese

- 4828423125 Shuri Castle on OpenStreetMap