| Siege of Bristol | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of English Civil War | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| Prince Rupert | Lord Fairfax | ||||||

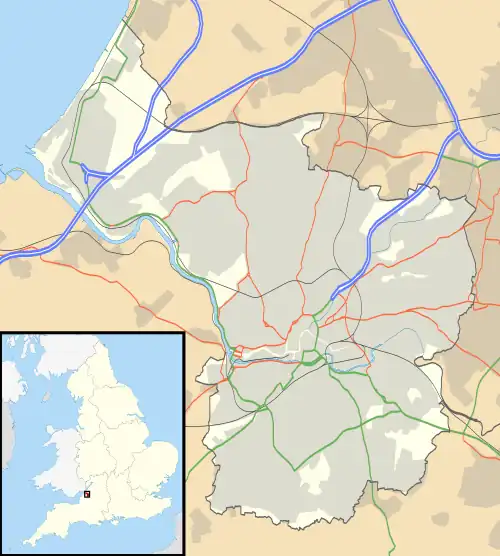

Bristol Location within Bristol | |||||||

The Second Siege of Bristol of the First English Civil War lasted from 23 August 1645 until 10 September 1645, when the Royalist commander Prince Rupert surrendered the city that he had captured from the Parliamentarians on 26 July 1643. The commander of the Parliamentarian New Model Army forces besieging Bristol was Lord Fairfax.

Context

After the Battle of Naseby in June 1645, it was clear that the war had turned decisively in favour of the Parliamentarians. Indeed, by the end of July, Prince Rupert was actively petitioning the king to end the war by treaty [1]. However, Charles believed he had enough men and munitions at his disposal to continue.[2] The holding of Bristol was vital to these plans. In the first instance, it was one of the only ports remaining in Royalist hands. Secondly, Charles had ordered a recruitment drive in Wales, and intended Bristol to be used to receive the raised troops. Indeed he was even considering moving his headquarters from Oxford to Bristol. [2]

Prelude

After reducing Bridgwater, Fairfax and the New Model Army turned back to clear away the Dorsetshire Clubmen and besiege Sherborne Castle. On the completion of this task, it was decided to besiege Bristol.[3]

Fairfax’s army was made up of 12,000 troops , whilst the defenders numbered just 1500 [1]. However, another Royalist army, commanded by Lord Goring lay to the west and Charles himself commanded an army in Oxford.

Preparations in Bristol

Prince Rupert ordered the town to prepare for a six-month siege. He ordered his men out to forage, had cattle driven into the town, and ordered large quantities of corn from Wales to assist those who could not afford to prepare themselves. [2] On 12 August, Rupert write to Charles stating that Bristol would be able to withstand a siege of four months. [2]

Despite these efforts, Bristol was in an extremely precarious position, with plague rife and concerns that the citizens may mutiny against the Royalists. [4] [2] Military issues also abounded: there had been no time to clear the surrounding countryside of cover, [4] the outer walls were extremely hard to defend — being over 4 miles in length and less than 5ft high in places — and men were deserting daily. [5]

On 3 September, Prince Rupert convened a Council of War. They considered three options:

- Breaking out with the cavalry

- Retreating to the inner walls

- Defending the outer walls

Option 1 had the obvious drawback of leaving the infantry abandoned. Similarly, option 2 left the general populace at risk. Therefore, it was decided to defend the outer walls. [2]

Preparations of the New Model Army

On 22 August the first units of the New Model Army arrived [2] under harassment by Royalist patrols (one of which managed to capture John Okey). [4] The bulk of the army arrived on the 23rd and invested Stapleton. [5]

Fairfax was careful to ensure that his army paid in ready cash for all goods consumed, and this, along with a growing antagonism towards the Royalists led to approximately 2000 of the local clubmen joining the camp. [5] On the 28th the clubmen took the fortress at Portishead from a Royalist garrison, removing possibility of Bristol being relieved from the sea. [5] [2] On 29 August a bridge was made across the Avon, allowing the New Model Army to encircle Bristol. [2]

During this time there were numerous dummy attacks in the nights, which were used to reduce the gunpowder and morale of the besieged town. [2]

Negotiations

On 31 August, Fairfax intercepted a letter from Goring stating that it would be at least three weeks before he could arrive to relieve the siege. Charles had left Oxford to recapture Hereford, but it was anticipated that he too would then turn to Bristol. Therefore Fairfax decided to take the town by force. [5]

On 4 September, summons for surrender was sent to Prince Rupert. The communication consisted of a formal summons, along with a personal note. Fairfax attempted to draw attention to the faction opposing Rupert within Charles’ court (led by George Digby). [5] [2] There is disagreement regarding the extent to which this tactic was effective, with some historians arguing Rupert knew too little about English politics to be compelled by Fairfax’s reasoning [5] whilst other authors claim the arguments resonated with Rupert and were a contributing factor in his eventual surrender [2].

Rupert spent the following days attempting to stall. [5] [2] He initially requested that permission be sought from the king to surrender. This was refused. He then asked for the summons to be sanctioned by Parliament. This too was refused. Rupert then opened negotiations for surrender. By 10 September it was clear that these were not being conducted in good faith and Fairfax’s patience was exhausted. [5]

Siege

At 2am on 10 September the attack began with the firing of four great guns. [2] As expected, the outer walls proved impossible to defend and fell easily. [5] Priors Hill fort held for three hours before it was eventually overwhelmed with scaling ladders. No quarter was offered and the entire garrison was killed. Simultaneously, clubmen in the south pushed back Royalists towards the centre of Bristol. [2]

The Royalists retreated to the inner walls but the town was clearly indefensible. They set fires in anticipation of surrender. [5] It was before 8am (less than six hours after the siege began) that the trumpet was sounded for ceasefire. [4]

Prince Rupert was escorted to Oxford with his men, conversing as he rode with the officers of the escort about peace and the future of his adopted country.[3]

Aftermath

King Charles, was stunned by the suddenness of the catastrophic loss of Bristol, and dismissed Rupert from all his offices and ordered him to leave England. In a letter to Rupert, Charles wrote "you assured me you would keep Bristol for four months. Did you keep it four days?" [1].

Some Whig historians have argued that the king was completely delusional in his belief that Bristol could be held [5]. They argue that his belief was so strong that the only explanation he could find was one of gross dereliction of duty. Others argue that he believed Rupert was to stage a coup, a belief stoked by his enemies at court — namely, Digby — who even went as far as to suggest he had been bribed to surrender. [4]

The fall of Bristol meant that Chester was the only important seaport remaining to connect the English Royalists with Ireland.[3] The war was by this point all but over. The resources to continue the fight collapsed in the south of England but the king managed to hold onto some fortified town for another 9 months before surrendering to the Scots.

Upon hearing of the surrender, the House of Commons voted to reinstate Nathaniel Fiennes to his seat. He had previously been disgraced after failing to hold Bristol in 1646, but it was now clear that the town was less defensible than assumed. [5]

Oliver Cromwell once again (as after Naseby) wrote to the Commons arguing in support of the Independent faction on the grounds that his men had fought and died for the cause of religious liberty. [4] His words were reprinted and led to an increase in the factional tension that would eventually end in the military coup of 1648.

Citations

- 1 2 3 Royle, Trevor (2005). Civil War: The War of the Three Kingdoms 1638-1660. Abacus. p. 354. ISBN 978-0-349-11564-1.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 Spencer, Charles (2008). Prince Rupert: The Last Cavalier. Phoenix. pp. 153–156. ISBN 978-0-7538-2401-6.

- 1 2 3 Atkinson 1911, 41. Fall of Bristol.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Hibbert, Christopher (1993). Cavaliers and Roundheads. BCA. p. 224. ISBN 0-246-13632-4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Gardiner, S. R. (1987). History of the Great Civil War. Windrush. pp. 312–318. ISBN 0-900075-05-8.

References

- Attribution

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Atkinson, Charles Francis (1911). "Great Rebellion". In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 12 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 403–421.