In contract theory, signalling (or signaling; see spelling differences) is the idea that one party (the agent) credibly conveys some information about itself to another party (the principal).

Although signalling theory was initially developed by Michael Spence based on observed knowledge gaps between organisations and prospective employees,[1] its intuitive nature led it to be adapted to many other domains, such as Human Resource Management, business, and financial markets.[2]

In Spence's job-market signaling model, (potential) employees send a signal about their ability level to the employer by acquiring education credentials. The informational value of the credential comes from the fact that the employer believes the credential is positively correlated with having the greater ability and difficulty for low-ability employees to obtain. Thus the credential enables the employer to reliably distinguish low-ability workers from high-ability workers.[1] The concept of signaling is also applicable in competitive altruistic interaction, where the capacity of the receiving party is limited.[3]

Introductory questions

Signalling started with the idea of asymmetric information (a deviation from perfect information), which relates to the fact that, in some economic transactions, inequalities exist in the normal market for the exchange of goods and services. In his seminal 1973 article, Michael Spence proposed that two parties could get around the problem of asymmetric information by having one party send a signal that would reveal some piece of relevant information to the other party.[1] That party would then interpret the signal and adjust their purchasing behaviour accordingly—usually by offering a higher price than if they had not received the signal. There are, of course, many problems that these parties would immediately run into.

- Effort: How much time, energy, or money should the sender (agent) spend on sending the signal?

- Reliability: How can the receiver (the principal, who is usually the buyer in the transaction) trust the signal to be an honest declaration of information?

- Stability: Assuming there is a signalling equilibrium under which the sender signals honestly and the receiver trusts that information, under what circumstances will that equilibrium break down?

Job-market signalling

In the job market, potential employees seek to sell their services to employers for some wage, or price. Generally, employers are willing to pay higher wages to employ better workers. While the individual may know their own level of ability, the hiring firm is not (usually) able to observe such an intangible trait—thus there is an asymmetry of information between the two parties. Education credentials can be used as a signal to the firm, indicating a certain level of ability that the individual may possess; thereby narrowing the informational gap. This is beneficial to both parties as long as the signal indicates a desirable attribute—a signal such as a criminal record may not be so desirable. Furthermore, signaling can sometimes be detrimental in the educational scenario, when heuristics of education get overvalued such as an academic degree, that is, despite having equivalent amounts of instruction, parties that own a degree get better outcomes—the sheepskin effect.

Spence 1973: "Job Market Signaling" paper

Assumptions and groundwork

Michael Spence considers hiring as a type of investment under uncertainty[1] analogous to buying a lottery ticket and refers to the attributes of an applicant which are observable to the employer as indices. Of these, attributes which the applicant can manipulate are termed signals. Applicant age is thus an index but is not a signal since it does not change at the discretion of the applicant. The employer is supposed to have conditional probability assessments of productive capacity, based on previous experience of the market, for each combination of indices and signals. The employer updates those assessments upon observing each employee's characteristics. The paper is concerned with a risk-neutral employer. The offered wage is the expected marginal product. Signals may be acquired by sustaining signalling costs (monetary and not). If everyone invests in the signal in the exactly the same way, then the signal can't be used as discriminatory, therefore a critical assumption is made: the costs of signalling are negatively correlated with productivity. This situation as described is a feedback loop: the employer updates their beliefs upon new market information and updates the wage schedule, applicants react by signalling, and recruitment takes place. Michael Spence studies the signalling equilibrium that may result from such a situation. He began his 1973 model with a hypothetical example:[1] suppose that there are two types of employees—good and bad—and that employers are willing to pay a higher wage to the good type than the bad type. Spence assumes that for employers, there's no real way to tell in advance which employees will be of the good or bad type. Bad employees aren't upset about this, because they get a free ride from the hard work of the good employees. But good employees know that they deserve to be paid more for their higher productivity, so they desire to invest in the signal—in this case, some amount of education. But he does make one key assumption: good-type employees pay less for one unit of education than bad-type employees. The cost he refers to is not necessarily the cost of tuition and living expenses, sometimes called out of pocket expenses, as one could make the argument that higher ability persons tend to enroll in "better" (i.e. more expensive) institutions. Rather, the cost Spence is referring to is the opportunity cost. This is a combination of 'costs', monetary and otherwise, including psychological, time, effort and so on. Of key importance to the value of the signal is the differing cost structure between "good" and "bad" workers. The cost of obtaining identical credentials is strictly lower for the "good" employee than it is for the "bad" employee. The differing cost structure need not preclude "bad" workers from obtaining the credential. All that is necessary for the signal to have value (informational or otherwise) is that the group with the signal is positively correlated with the previously unobservable group of "good" workers. In general, the degree to which a signal is thought to be correlated to unknown or unobservable attributes is directly related to its value.

The result

Spence discovered that even if education did not contribute anything to an employee's productivity, it could still have value to both the employer and employee. If the appropriate cost/benefit structure exists (or is created), "good" employees will buy more education in order to signal their higher productivity.

The increase in wages associated with obtaining a higher credential is sometimes referred to as the “sheepskin effect”,[4] since “sheepskin” informally denotes a diploma. It is important to note that this is not the same as the returns from an additional year of education. The "sheepskin" effect is actually the wage increase above what would normally be attributed to the extra year of education. This can be observed empirically in the wage differences between 'drop-outs' vs. 'completers' with an equal number of years of education. It is also important that one does not equate the fact that higher wages are paid to more educated individuals entirely to signalling or the 'sheepskin' effects. In reality, education serves many different purposes for individuals and society as a whole. Only when all of these aspects, as well as all the many factors affecting wages, are controlled for, does the effect of the "sheepskin" approach its true value. Empirical studies of signalling indicate it as a statistically significant determinant of wages, however, it is one of a host of other attributes—age, sex, and geography are examples of other important factors.

The model

To illustrate his argument, Spence imagines, for simplicity, two productively distinct groups in a population facing one employer. The signal under consideration is education, measured by an index y and is subject to individual choice. Education costs are both monetary and psychic. The data can be summarized as:

| Group | Marginal Product | Proportion of population | Cost of education level y |

|---|---|---|---|

| I | 1 | y | |

| II | 2 | y/2 |

Suppose that the employer believes that there is a level of education y* below which productivity is 1 and above which productivity is 2. Their offered wage schedule W(y) will be:

Working with these hypotheses Spence shows that:

- There is no rational reason for someone choosing a different level of education from 0 or y*.

- Group I sets y=0 if 1>2-y*, that is if the return for not investing in education is higher than investing in education.

- Group II sets y=y* if 2-y*/2>1, that is the return for investing in education is higher than not investing in education.

- Therefore, putting the previous two inequalities together, if 1<y*<2, then the employer's initial beliefs are confirmed.

- There are infinite equilibrium values of y* belonging to the interval [1,2], but they are not equivalent from the welfare point of view. The higher y* the worse off is Group II, while Group I is unaffected.

- If no signaling takes place each person is paid their unconditional expected marginal product . Therefore, Group, I is worse off when signaling is present.

In conclusion, even if education has no real contribution to the marginal product of the worker, the combination of the beliefs of the employer and the presence of signalling transforms the education level y* in a prerequisite for the higher paying job. It may appear to an external observer that education has raised the marginal product of labor, without this necessarily being true.

Another model

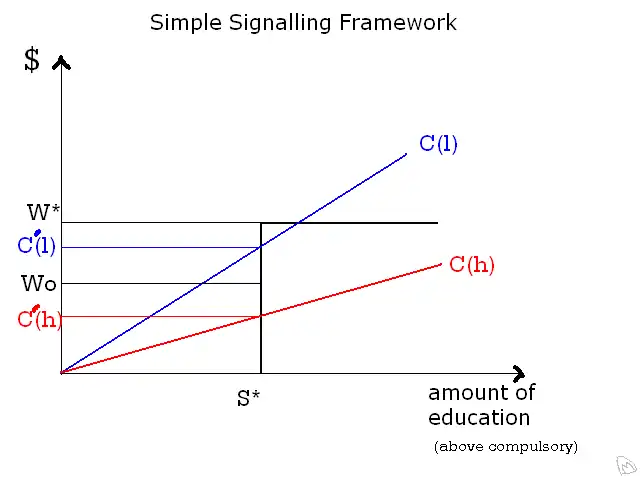

For a signal to be effective, certain conditions must be true. In equilibrium, the cost of obtaining the credential must be lower for high productivity workers and act as a signal to the employer such that they will pay a higher wage.

In this model it is optimal for the higher ability person to obtain the credential (the observable signal) but not for the lower ability individual. The table shows the outcome of low ability person l and high ability person h with and without signal S*:

| Person | Without Signal | With Signal | Will the person obtain the signal S*? |

|---|---|---|---|

| l | Wo | W* - C'(l) | No, because Wo > W* - C'(l) |

| h | Wo | W* - C'(h) | Yes, because Wo < W* - C'(h) |

The structure is as follows: There are two individuals with differing abilities (productivity) levels.

- A higher ability / productivity person: h

- A lower ability / productivity person : l

The premise for the model is that a person of high ability (h) has a lower cost for obtaining a given level of education than does a person of lower ability (l). Cost can be in terms of monetary, such as tuition, or psychological, stress incurred to obtain the credential.

- Wo is the expected wage for an education level less than S*

- W* is the expected wage for an education level equal or greater than S*

For the individual:

- Person(credential) - Person(no credential) ≥ Cost(credential) → Obtain credential

- Person(credential) - Person(no credential) < Cost(credential) → Do not obtain credentia

Thus, if both individuals act rationally it is optimal for person h to obtain S* but not for person l so long as the following conditions are satisfied.

Edit: note that this is incorrect with the example as graphed. Both 'l' and 'h' have lower costs than W* at the education level. Also, Person(credential) and Person(no credential) are not clear.

Edit: note that this is ok as for low type "l": , and thus low type will choose Do not obtain credential.

Edit: For there to be a separating equilibrium the high type 'h' must also check their outside option; do they want to choose the net pay in the separating equilibrium (calculated above) over the net pay in the pooling equilibrium. Thus we also need to test that: Otherwise high type 'h' will choose Do not obtain credential of the pooling equilibrium.

For the employers:

- Person(credential) = E(Productivity | Cost(credential) ≤ Person(credential) - Person(no credential))

- Person(no credential) = E(Productivity | Cost(credential) > Person(credential) - Person(no credential))

In equilibrium, in order for the signalling model to hold, the employer must recognize the signal and pay the corresponding wage and this will result in the workers self-sorting into the two groups. One can see that the cost/benefit structure for a signal to be effective must fall within certain bounds or else the system will fail.[5]

IPOs

Signaling typically occurs in an IPO, where a company issues out shares to the public market to raise equity capital. This arises due to information asymmetry between potential investors and the company raising capital. Given firms are private before an IPO, prospective investors have limited information about the firm's true value or future prospects, which may lead to market inefficiencies and mispricing. To overcome this information asymmetry, firms may use signaling to communicate their true value to potential investors.

Leland and Pyle (1977) analyzed the role of signals within the process of an IPO, finding that companies with good future perspectives and higher possibilities of success ("good companies") should always send clear signals to the market when going public, i.e. the owner should keep control of a significant percentage of the company. In order for this signal to be perceived as reliable, the signal must be too costly to be imitated by "bad companies". By not providing a signal to the market, asymmetric information will result in adverse selection in the IPO market.

Various forms of signaling have also been observed during IPOs, especially when companies underprice the offered share price to prospective investors. Underpricing can be explained by prospect theory, which suggests that investors tend to be more risk-averse when it comes to gains than losses. Hence, when a company offers its shares at a discount to their true value, it creates the perception of a gain for investors, which can increase demand for the shares and lead to a higher aftermarket price. This excess demand also sends a positive signal to the market that the firm is undervalued, as the issuer signals to the market that they are leaving money on the table - defined as number of shares sold times the difference between the first-day closing market price and the offer price. This represents a substantial indirect cost to the issuing firm, but allows initial investors to achieve sizeable financial returns at the very first day of trading.[6]

In spite of leaving money on the table, underpricing is still beneficial to the firm because it allows them to raise more capital than they would have if they had priced the shares at their true value, assuming a higher price at market close. This also helps to generate positive publicity and media attention for the issuer, providing further signaling for a company's positive growth prospects.

Additionally, firms can also signal their quality to the market through their choice of an underwriter. A reputable underwriter, such as a well-known investment bank, can signal that the issuing firm is of high quality and has a strong likelihood of future success. Considering the underwriter's role in providing due diligence and expertise in the IPO process, it is unlikely for an underwriter to associate themselves with firms that have a high likelihood of failure. This helps increase the credibility of the issuing firm, and hence the share capital on offer. Additionally, the underwriter's compensation structure, which is typically based on the success of the IPO, provides an incentive for the underwriter to ensure the success of the IPO. Therefore, by choosing a reputable underwriter, the issuing firm can signal its quality to potential investors, which increases the demand for its shares and can potentially lead to a higher aftermarket price.[7]

However, while signaling mechanisms can benefit issuers, they can also impose costs on investors. Information asymmetry can make it difficult for investors to distinguish between true signals of quality and mere attempts to manipulate the market. Moreover, the use of signals can lead to a "winner's curse" where investors overpay for shares that are not worth the price paid.[8] Thus, understanding the costs and benefits of different signaling mechanisms is crucial in improving market efficiency and reducing information asymmetry problems.

Brands

The development of brand capital is an important strategy firms use to signal quality and reliability to consumers. Waldfogel and Chen (2006) studied the impact of retailers providing information on internet retail sites to the importance of branding as a signalling mechanism.[9] Their study used web visits to branded vendors, unbranded vendors and third party sites which took data and collated it for consumers labelled information intermediaries.[10] The paper did not directly measure the outcome on consumer spending because it did not include actual consumer expenditure on branded or unbranded products.[11] It further acknowledged there is the potential consumer spending deviates from visiting behaviour.[12] Nonetheless, it found using information intermediaries increases the number of consumer visits to unbranded vendors while it also depresses visits to branded vendors.[13] The authors concluded by observing that while branding is a market concentrating mechanism, the internet has the potential to result in reducing market concentration as information provision undermines the effectiveness of brand spending.[12] The extent of its effectiveness depends on the ease and cost effectiveness by which information can be provided.[14]

Altruism and Signalling

Various studies and experiments have analysed signalling in the context of altruism. Historically, due to the nature of small communities, cooperation was particularly important to ensure human flourishing.[15] Signalling altruism is critical in human societies because altruism is a method of signalling willingness to cooperate.[16] Studies indicate that altruism boosts an individual’s reputation in the community, which in turn enables the individual to reap greater benefits from reputation including increased assistance if they are in need.[16] There is often difficulty in distinguishing between pure altruists who do altruistic acts expecting no benefit to themselves whatsoever and impure altruists who do altruistic acts expecting some form of benefit. Pure altruists will be altruistic irrespective of whether there is anyone observing their conduct, whereas impure altruists will give where their altruism is observed and can be reciprocated.

Laboratory experiments conducted by behavioural economists has found that pure altruism is relatively rare. A study conducted by Dana, Weber and Xi Kuang found that in dictator games, the level of proposing 5:5 distributions were much higher when proposers could not excuse their choice by reference to moral considerations.[17] In games where voters were provided by the testers with a mitigating reason they could cite to the other person to explain their decision, 6:1 splits were much more common than fair 50:50 split.[18]

Empirical research in real world scenarios shows charitable giving diminishes with anonymity.[19] Anonymous donations are much less common than non-anonymous donations.[19] In respect to donations to a national park, researchers found participants were 25% less generous when their identities were not revealed relative to when they were.[20] They also found donations were subject to reference effects.[20] Participants on average gave less money where researchers told them the average donation was lower than in other instances where the researchers told participants the amount of the average donation was higher.[20]

A study on charity runs where donors could reveal only their name, only the amount, their name and amount or remain completely anonymous with no reference to donation amount had three main findings. First, donors that gave a significant amount of money revealed the amounts donated but were more likely to not reveal their names.[21] Second, those who gave small donations were more likely to reveal their names but hide their donations.[21] Third, average donors were most likely to reveal both name and amount information.[21] The researchers noted small donor donations were consistent with free riding behaviour where participants would try and obtain reputation enhancement by noting their donation, without having to donate at levels that would otherwise be necessary to get the same boost if amount information was published.[22] Average donors revealed name and amount to also gain reputation.[22] With respect to high donors, the researchers thought two alternatives were possible. Either, donors did not reveal names because despite high donations signalling high cost altruism there were larger reputational drawbacks to what is perceived to be showboating,[22] or large contributors were genuinely altruistic and wanted to signal the importance of the cause.[23] Revealing amount values the authors thought is more consistent with the latter hypothesis.[23]

eBay Motors' Price Premium

Signalling has been studied and proposed as a means to address asymmetric information in markets for "lemons".[24] Recently, signalling theory has been applied in used cars market such as eBay Motors. Lewis (2011)[25] examines the role of information access and shows that the voluntary disclosure of private information increases the prices of used cars on eBay. Dimoka et al. (2012)[26] analyzed data from eBay Motors on the role of signals to mitigate product uncertainty. Extending the information asymmetry literature in consumer behavior literature from the agent (seller) to the product, authors theorized and validated the nature and dimensions of product uncertainty, which is distinct from, yet shaped by, seller uncertainty. Authors also found information signals (diagnostic product descriptions and third-party product assurances) to reduce product uncertainty, which negatively affect price premiums (relative to the book values) of the used cars in online used cars markets.

Internet-Based Hospitality Exchange

In internet-based hospitality exchange networks such as BeWelcome and Warm Showers, hosts do not expect to receive payments from travelers. The relation between traveler and host is rather shaped by mutual altruism. Travelers send homestay requests to the hosts, which the hosts are not obligated to accept. Both networks as non-profit organizations grant trustworthy teams of scientists access to their anonymized data for publication of insights to the benefit of humanity. In 2015, datasets from BeWelcome and Warm Showers were analyzed.[27] Analysis of 97,915 homestay requests from BeWelcome and 285,444 homestay requests from Warm Showers showed general regularity — the less time is spent on writing a homestay request, the less is the probability of being accepted by a host. Low-effort communication aka 'copy and paste requests' obviously sends the wrong signal.[27]

Outside options

Most signalling models are plagued by a multiplicity of possible equilibrium outcomes.[28] In a study published in the Journal of Economic Theory, a signalling model has been proposed that has a unique equilibrium outcome.[29] In the principal-agent model it is argued that an agent will choose a large (observable) investment level when he has a strong outside option. Yet, an agent with a weak outside option might try to bluff by also choosing a large investment, in order to make the principal believe that the agent has a strong outside option (so that the principal will make a better contract offer to the agent). Hence, when an agent has private information about his outside option, signalling may mitigate the hold-up problem.

Foreign policy and international relations

Due to the nature of international relations and foreign policy, signaling has long been a topic of interest when analyzing the actions of the agents involved. This study of signaling regarding foreign policy has further allowed economists and academics to understand the actions and reactions of foreign bodies when presented with varying information. Typically when interacting with one another, the actions of these foreign parties are heavily dependent on the proposed actions and reactions of each other.[30] In many cases however, there is an asymmetry of information between the two parties with both looking to aid their own non-mutually beneficial interests.

Costly signaling

In foreign policy, it is common to see game theory problems such as the prisoner’s dilemma and chicken game occur as the different parties both have a dominating strategy regardless of the actions of the other party. In order to signal to the other parties, and furthermore for the signal to be credible, strategies such as tying hands and sinking costs are often implemented. These are examples of costly signals which typically present some form of assurance and commitment in order to show that the signal is credible and the party receiving the signal should act on the information given.[30] Despite this however, there is still much contention as to whether, in practice, costly signaling is effective. In studies by Quek (2016) it was suggested that decision makers such as politicians and leaders don't seem to interpret and understand signals the way that models suggest they should.[31]

| B Cooperate | B Defect | |

|---|---|---|

| A Cooperate | 3,3 | 0,5 |

| A Defect | 5,0 | 1,1 |

| B Swerve | B Don't Serve | |

|---|---|---|

| A Swerve | 0,0 | -1,1 |

| A Don't Swerve | 1,-1 | -5,-5 |

Sinking costs and Tying hands

A costly signal in which the cost of an action is incurred upfront ("ex ante") is a sunk cost. An example of this would be the mobilization of an army as this sends a clear signal of intentions and the costs are incurred immediately.

When the cost of the action is incurred after the decision is made ("ex post") it is considered to be tying hands. A common example is an alliance which does not have a large initial monetary cost yet ties the hands of the parties, as either party would incur significant costs if they abandoned the other party, especially in crises.

Theoretically both sinking costs and tying hands are valid forms of costly signaling however they have garnered much criticism due to differing beliefs regarding the overall effectiveness of the methods in altering the likelihood of war. Recent studies such as the Journal of Conflict Resolution suggest that sinking costs and tying hands are both effective in increasing credibility. This was done by finding how the change in the costs of costly signals vary their credibility. Prior to this research studies conducted were binary and static by nature, limiting the capability of the model.[32] This increased the validity of the use of these signaling mechanisms in foreign diplomacy.

Effectiveness of signaling through time

The initial research into signaling suggested that it was an effective tool in order to manage foreign economic and military affairs however, with time and more thorough analysis problems began to present themselves, these being:

- Whether or not the extent to which the signal is received and acted upon may not justify the cost of the signal

- Parties and those who govern them are able to signal in more ways than just through actions

- Different signals often provoke different responses from different parties (heterogeneity plays a large part in the effectiveness of signals)[30]

In Fearon’s original models (Bargaining model of war) the model was simple in that a party would display their intentions, their intended audience would then interpret the signals and act upon them. Thus, creating a perfect scenario which validates the use of signaling. Later in works by Slantchev (2005), it was suggested that due to the nature of using military mobilization as a signal, despite having intentions to avoid war can increase tensions and thus both be a sunk cost and can tie the party’s hands. Furthermore Yarhi-Milo, Kertzer and Renshon (2017) were able to use a more dynamic model to assess the effectiveness of these signals given varying cost levels and reaction levels.[31]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 Michael Spence (1973). "Job Market Signaling". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 87 (3): 355–374. doi:10.2307/1882010. JSTOR 1882010.

- ↑ Connelly, B. L.; Certo, S. T.; Ireland, R. D.; Reutzel, C. R. (2011). "Signaling theory: A review and assessment". Journal of Management. 37 (1): 39–67. doi:10.1177/0149206310388419. S2CID 145334039.

- ↑ Lotem, A., M. Fishman, and L. Stone. 2003. From reciprocity to unconditional altruism through signaling benefits. Proc. R. Soc. Lond. B. 270: 200.

- ↑ Hungerford, Thomas; Solon, Gary (1987). "Sheepskin Effects in the Returns to Education". Review of Economics and Statistics. 69 (1): 175–177. doi:10.2307/1937919. JSTOR 1937919.

- ↑ http://economics.mit.edu/files/552

- ↑ Loughran, Tim; Ritter, Jay (2004). "Why Has IPO Underpricing Changed over Time?". Financial Management. 33 (3): 5–37. ISSN 0046-3892. JSTOR 3666262.

- ↑ Carter, Richard B.; Dark, Frederick H.; Singh, Ajai K. (1998). "Underwriter Reputation, Initial Returns, and the Long-Run Performance of IPO Stocks". The Journal of Finance. 53 (1): 285–311. doi:10.1111/0022-1082.104624. ISSN 0022-1082. JSTOR 117442.

- ↑ Vong, Anna P. I.; Trigueiros, Duarte (August 2009). "An empirical extension of Rock's IPO underpricing model to three distinct groups of investors". Applied Financial Economics. 19 (15): 1257–1268. doi:10.1080/09603100802570408. ISSN 0960-3107. S2CID 55865031.

- ↑ Waldfogel, Joel; Chen, L (2006). "Does Information Undermine Brand? Information Intermediary Use and Preference for Branded Web Retailers". Journal of Industrial Economics. 54 (4): 425–449. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.201.155. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6451.2006.00295.x. S2CID 153526568.

- ↑ Waldfogel and Chen (2006), p 429.

- ↑ Waldfogel and Chen (2006), p 427.

- 1 2 Waldfogel and Chen (2006), p. 448.

- ↑ Waldfogel and Chen (2006), p. 447.

- ↑ Waldfogel and Chen (2006), p .427.

- ↑ Mokos, Judit; Scheuring, Istvan (2019). "Altruism, costly signaling, and withholding information in a sport charity campaign". Evolution, Mind and Behaviour. 17: 10–18. doi:10.1556/2050.2019.00007. hdl:10831/58264. S2CID 213610349.

- 1 2 Mokos and Scheuring, (2019), p.10.

- ↑ Cartwright, Edward (2018). Behavioural Economics (Third ed.). London: Routledge. p. 357.

- ↑ Cartwright (2018), p.357-358.

- 1 2 Cartwright (2018), p.357.

- 1 2 3 Cartwright (2018), p.358.

- 1 2 3 Mokos and Scheuring, (2019), p.13.

- 1 2 3 Mokos and Scheuring, (2019), p.14.

- 1 2 Mokos and Scheuring, (2019), p.15.

- ↑ Akerlof, G. A. (1970). The market for" lemons": Quality uncertainty and the market mechanism. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 488-500.

- ↑ Lewis, Gregory (2011). "Asymmetric Information, Adverse Selection and Online Disclosure: The Case of eBay Motors". American Economic Review. 101 (4): 1535–1546. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.232.8552. doi:10.1257/aer.101.4.1535.

- ↑ Dimoka, Angelika; Hong, Yili; Pavlou, Paul (2012). "On Product Uncertainty in Online Markets: Theory and Evidence". MIS Quarterly. 36 (2): 395–426. doi:10.2307/41703461. JSTOR 41703461. S2CID 8963257.

- 1 2 Rustam Tagiew; Dmitry I. Ignatov; Radhakrishnan Delhibabu (2015). Economics of Internet-Based Hospitality Exchange. (IEEE/WIC/ACM) International Conference on Web Intelligence and Intelligent Agent Technology (WI-IAT). Singapore. pp. 493–498. arXiv:1501.06941. doi:10.1109/WI-IAT.2015.89.

- ↑ Fudenberg, Drew; Tirole, Jean (1991). Game Theory. MIT Press.

- ↑ Goldlücke, Susanne; Schmitz, Patrick W. (2014). "Investments as signals of outside options". Journal of Economic Theory. 150: 683–708. doi:10.1016/j.jet.2013.12.001.

- 1 2 3 Gartzke, Erik; Carcelli, Shannon; Gannon, J Andres; Zhang, Jiakun Jack (August 2017). "Signaling in Foreign Policy" (PDF). Oxford Research Encyclopedia of Politics: 30.

- 1 2 Yarhi-Milo, Keren; Kertzer, Joshua D; Renshon, Jonathon (2018). "Tying Hands, Sinking Costs and Leader Attributes" (PDF). Journal of Conflict Resolution. 62 (10): 2150–2179. doi:10.1177/0022002718785693. S2CID 150334324 – via Harvard University.

- ↑ Quek, Kai (19 January 2021). "Four Costly Signaling Mechanisms". American Political Science Review. 115 (2): 537–549. doi:10.1017/S0003055420001094. S2CID 232422457 – via Cambridge University Press.

Further reading

- Michael Spence (1973). "Job Market Signaling". Quarterly Journal of Economics. 87 (3): 355–374. doi:10.2307/1882010. JSTOR 1882010. paper

- Michael Spence (2002). "Signaling in Retrospect and the Informational Structure of Markets". American Economic Review. 92 (3): 434–459. doi:10.1257/00028280260136200.(also available as his Nobel Prize lecture PDF)

- Andrew Weiss (1995). "Human Capital vs. Signaling Explanations of Wages". The Journal of Economic Perspectives. 9 (4): 133–154. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.718.3629. doi:10.1257/jep.9.4.133.

- Dimoka, Angelika; Hong, Yili; Pavlou, Paul (June 2012). "On Product Uncertainty in Online Markets: Theory and Evidence". MIS Quarterly. 36 (2): 395–426. doi:10.2307/41703461. JSTOR 41703461. S2CID 8963257.

- Waldfogel, Joel; Chen, L (2006). "Does Information Undermine Brand? Information Intermediary Use and Preference for Branded Web Retailers". Journal of Industrial Economics. 54 (4): 425–449. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.201.155. doi:10.1111/j.1467-6451.2006.00295.x. S2CID 153526568.

- Lewis, Gregory (2011). "Asymmetric Information, Adverse Selection and Online Disclosure: The Case of eBay Motors". American Economic Review. 101 (4): 1535–1546. CiteSeerX 10.1.1.232.8552. doi:10.1257/aer.101.4.1535.