Silver certificates are a type of representative money issued between 1878 and 1964 in the United States as part of its circulation of paper currency.[1] They were produced in response to silver agitation by citizens who were angered by the Fourth Coinage Act, which had effectively placed the United States on a gold standard.[2] The certificates were initially redeemable for their face value of silver dollar coins and later (for one year from June 24, 1967, to June 24, 1968) in raw silver bullion.[1] Since 1968 they have been redeemable only in Federal Reserve Notes and are thus obsolete, but still valid legal tender at their face value and thus are still an accepted form of currency.[1]

Large-size silver certificates, generally 1.5 in (38 mm) longer and 0.5 in (13 mm) wider than modern U.S. paper currency, (1878 to 1923)[nb 1] were issued initially in denominations from $10 to $1,000 (in 1878 and 1880)[4][5] and in 1886 the $1, $2, and $5 were authorized.[5][6] In 1928, all United States bank notes were re-designed and the size reduced.[7] The small-size silver certificate (1928–1964) was only regularly issued in denominations of $1, $5, and $10.[8] The complete type set below is part of the National Numismatic Collection at the Smithsonian's National Museum of American History.

History

The Coinage Act of 1873 intentionally[9][10] omitted language authorizing the coinage of "standard"[2] silver dollars[11] and ended the bimetallic standard[12] that had been created by Alexander Hamilton.[13][nb 2] While the Coinage Act of 1873 stopped production of silver dollars, it was the 1874 adoption of Section 3568 of the Revised Statutes that actually removed legal tender status from silver certificates in the payment of debts exceeding five dollars.[15] By 1875 business interests invested in silver (e.g., Western banks, mining companies) wanted the bimetallic standard restored. People began to refer to the passage of the Act as the Crime of '73. Prompted by a sharp decline in the value of silver in 1876, Congressional representatives from Nevada and Colorado, states responsible for over 40% of the world's silver yield in the 1870s and 1880s,[16] began lobbying for change. Further public agitation for silver use was driven by fear that there was not enough money in the community.[17] Members of Congress claimed ignorance that the 1873 law would lead to the demonetization of silver,[18] despite having had three years to review the bill prior to enacting it to law.[19] Some blamed the passage of the Act on a number of external factors including a conspiracy involving foreign investors and government conspirators.[11] In response, the Bland–Allison Act, as it came to be known, was passed by Congress (over a presidential veto)[20] on February 28, 1878. It did not provide for the "free and unlimited coinage of silver" demanded by Western miners, but it did require the United States Treasury to purchase between $2 million and $4 million of silver bullion per month[21][22] from mining companies in the West, to be minted into coins.[nb 3]

Large-size silver certificates

.jpg.webp)

The first silver certificates (Series 1878) were issued in denominations of $10 through $1,000.[nb 4] Reception by financial institutions was cautious.[25] While more convenient and less bulky than dollar coins, the silver certificate was not accepted for all transactions.[26] The Bland–Allison Act established that they were "receivable for customs, taxes, and all public dues,"[20] and could be included in bank reserves,[22] but silver certificates were not explicitly considered legal tender for private interactions (i.e., between individuals).[22] Congress used the National Banking Act of July 12, 1882, to clarify the legal tender status of silver certificates[27] by clearly authorizing them to be included in the lawful reserves of national banks.[28] A general appropriations act of August 4, 1886, authorized the issue of $1, $2, and $5 silver certificates.[6][29] The introduction of low-denomination currency (as denominations of U.S. Notes under $5 were put on hold) greatly increased circulation.[30] Over the 12-year lifespan of the Bland–Allison Act, the United States government would receive a seigniorage amounting to roughly $68 million (between $3 and $9 million per year),[31] while absorbing over 60% of U.S. silver production.[31]

Small-size silver certificates

Treasury Secretary Franklin MacVeagh (1909–13) appointed a committee to investigate possible advantages (e.g., reduced cost, increased production speed) to issuing smaller sized United States banknotes.[32] Due in part to the outbreak of World War I and the end of his appointed term, any recommendations may have stalled. On August 20, 1925, Treasury Secretary Andrew W. Mellon appointed a similar committee and in May 1927 accepted their recommendations for the size reduction and redesign of U.S. banknotes.[32] On July 10, 1929, the new small-size currency was issued.[33]

In keeping with the verbiage on large-size silver certificates, all the small-size Series 1928 certificates carried the obligation "This certifies that there has (or have) been deposited in the Treasury of the United States of America X silver dollar(s) payable to the bearer on demand" or "X dollars in silver coin payable to the bearer on demand". This required that the Treasury maintain stocks of silver dollars to back and redeem the silver certificates in circulation. Beginning with the Series 1934 silver certificates the wording was changed to "This certifies that there is on deposit in the Treasury of the United States of America X dollars in silver payable to the bearer on demand." This freed the Treasury from storing bags of silver dollars in its vaults, and allowed it to redeem silver certificates with bullion or silver granules, rather than silver dollars. Years after the government stopped the redemption of silver certificates for silver, large quantities of silver dollars intended specifically to satisfy the earlier obligation for redemption in silver dollars were found in Treasury vaults.

As was usual with currency during this period, the year date on the bill did not reflect when it was printed, but rather a major design change. Under the Silver Purchase Act of 1934, the authority to issue silver certificates was given to the U.S. Secretary of Treasury.[34] Additional changes, particularly when either of the two signatures was altered, led to a letter being added below the date. One notable exception was the Series 1935G $1 silver certificate, which included notes both with and without the motto "In God We Trust" on the reverse. 1935 dated one dollar certificates lasted through the letter "H", after which new printing processes began the 1957 series.[35] In some cases printing plates were used until they wore out, even though newer ones were also producing notes, so the sequencing of signatures may not always be chronological. Thus some of the 1935 dated one dollar certificates were issued as late as 1963.[36]

World War II Issues

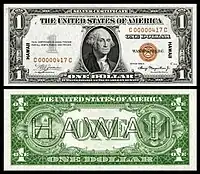

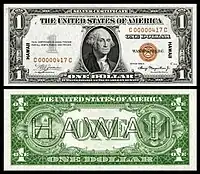

In response to the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbor, the Hawaii overprint note was ordered from the Bureau of Engraving and Printing on June 8, 1942 (all were made-over 1934–1935 bills).[33] Issued in denominations of $1, $5, $10, and $20, only the $1 was a silver certificate, the others were Federal Reserve Notes.[37] Stamped "HAWAII" (in small solid letters on the obverse and large letters on the reverse), with the Treasury seal and serial numbers in brown instead of the usual blue, these notes could be demonetized in the event of a Japanese invasion.[38] Additional World War II emergency currency was issued in November 1942 for circulation in Europe and Northern Africa.[33] Printed with a bright yellow seal, these notes ($1, $5, and $10) could be demonetized should the United States lose its position in the European or North African campaigns.[37]

"Star notes"

When a bill is damaged in printing it is normally replaced by another one (the star replaces a letter at the edge of the note). To keep the amounts issued consistent, these replacement banknotes are normally indicated by a star in the separately sequenced serial number. For silver certificates this asterisk appears at the beginning of the serial number.[39]

End of the silver certificates

In the nearly three decades since passage of the Silver Purchase Act of 1934, the annual demand for silver bullion rose steadily from roughly 11 million ounces (1933) to 110 million ounces (1962).[40] The Acts of 1939 and 1946 established floor prices for silver of 71 cents and 90.5 cents (respectively) per ounce.[40] Predicated on an anticipated shortage of silver bullion,[41][42] Public Law 88-36 (PL88-36) was enacted on June 4, 1963, which repealed the Silver Purchase Act of 1934, and the Acts of July 6, 1939, and July 31, 1946,[43] while providing specific instruction regarding the disposition of silver held as reserves against issued certificates and the price at which silver may be sold.[nb 5] It also amended the Federal Reserve Act to authorize the issue of lower denomination notes (i.e., $1 and $2),[43] allowing for the gradual retirement (or swapping out process) of $1 silver certificates and releasing silver bullion from reserve.[42] In repealing the earlier laws, PL88-36 also repealed the authority of the Secretary of the Treasury to control the issue of silver certificates. By issuing Executive Order 11110, President John F. Kennedy was able to continue the Secretary's authority.[44] While retaining their status as legal tender, the silver certificate had effectively been retired from use.[33]

In March 1964, Secretary of the Treasury C. Douglas Dillon halted redemption of silver certificates for silver dollar coins; during the following four years, silver certificates were redeemable in uncoined silver "granules".[41] All redemption in silver ceased on June 24, 1968.[1] While there are some exceptions (particularly for some of the very early issues as well as the experimental bills) the vast majority of small sized one dollar silver certificates, especially non-star or worn bills of the 1935 and 1957 series, are worth little or nothing above their face values. They can still occasionally be found in circulation.

Issue

Large-size United States silver certificates (1878–1923)

Series and varieties

| Series | Value | Features/varieties |

|---|---|---|

| 1878 and 1880[nb 6] |

|

In addition to the two engraved signatures customary on United States banknotes (the Register of the Treasury and Treasurer of the United States), the first issue of the Series 1878 notes (similar to the early Gold Certificate) included a third signature of one of the Assistant Treasurers of the United States (in New York, San Francisco, or Washington DC).[47] Known as a countersigned or triple-signature note, this feature existed for the first run of notes issued in 1880, but was then removed from the remaining 1880 issues.[5] |

| 1886 |

|

The Act of August 4, 1886, authorized the issue of lower denomination ($1, $2, and $5) silver certificates.[6] Similar to the Series 1878/1880 notes, the Treasury seal characteristics (size, color, and style) varies with the change of the Treasury signatures.[48] The series is known for the ornate engraving on the reverse of the note. |

| 1891 |

|

The Bureau of Engraving and Printing introduced the process of "resizing" paper for Series 1891 notes.[49] |

| 1896 |

|

The Educational Series is considered to be the most artistically designed bank notes printed by the United States.[5] |

| 1899 |

|

Large-size silver certificates from the Series of 1899 forward have a blue Treasury seal and serial numbers.[50] |

| 1908 | $10 | |

| 1923 |

|

|

Complete typeset

| Value | Series | Fr.[nb 7] | Image | Portrait | Signature & seal varieties[nb 8] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| $1 | 1886 | Fr.217 |  |

Martha Washington | |

| $1 | 1891 | Fr.223 |  |

Martha Washington | |

| $1 | 1896 | Fr.224 | .jpg.webp) |

Allegory History Instructing Youth (obv); George Washington & Martha Washington (rev) | |

| $1 | 1899 | Fr.226 |  |

Abraham Lincoln & Ulysses Grant |

|

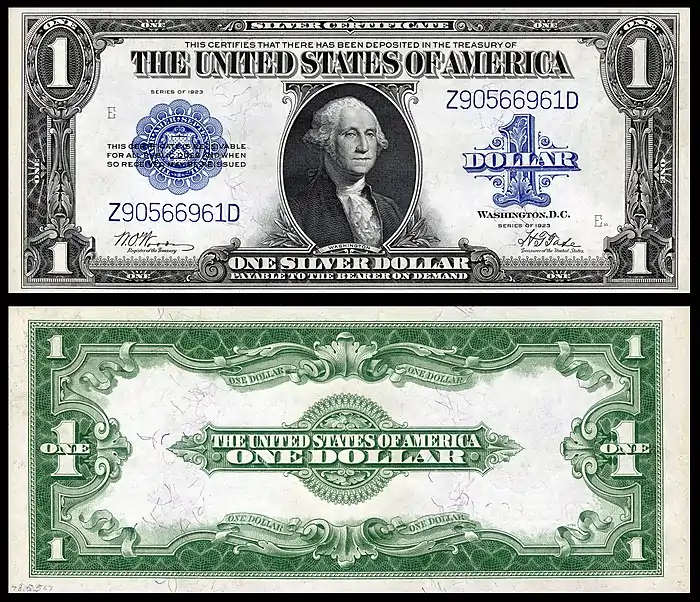

| $1 | 1923 | Fr.239 |  |

George Washington | |

| $2 | 1886 | Fr.242 |  |

Winfield Scott Hancock | |

| $2 | 1891 | Fr.246 |  |

William Windom | |

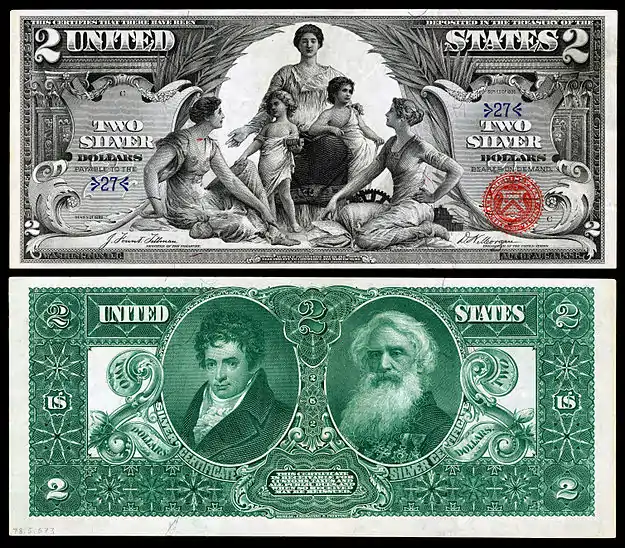

| $2 | 1896 | Fr.247 |  |

Allegory of Science Presenting Steam and Electricity to Commerce and Manufacture (obv); Robert Fulton & Samuel F.B. Morse (rev) | |

| $2 | 1899 | Fr.249 |  |

George Washington |

|

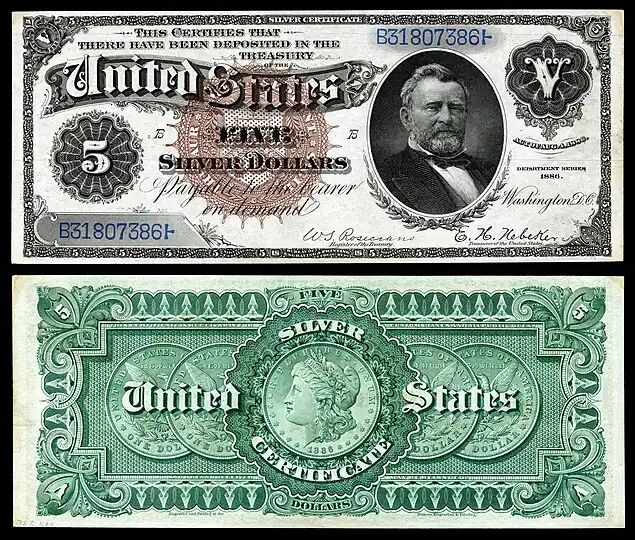

| $5 | 1886 | Fr.264 |  |

Ulysses Grant | |

| $5 | 1891 | Fr.267 |  |

Ulysses Grant | |

| $5 | 1896 | Fr.270 |  |

Allegory of Electricity Presenting Light to the World (obv); Ulysses Grant & Philip Sheridan (rev) | |

| $5 | 1899 | Fr.271 |  |

Running Antelope |

|

| $5 | 1923 | Fr.282 | .jpg.webp) |

Abraham Lincoln | 282 – Speelman and White – blue |

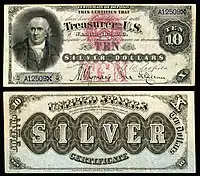

| $10 | 1878 | Fr.285a* |  |

Robert Morris |

|

| $10 | 1880 | Fr.287 |  |

Robert Morris |

|

| $10 | 1886 | Fr.291 |  |

Thomas Hendricks | |

| $10 | 1891 | Fr.298 |  |

Thomas Hendricks | |

| $10 | 1908 | Fr.302 |  |

Thomas Hendricks | |

| $20 | 1878 | Fr.307 |  |

Stephen Decatur |

|

| $20 | 1880 | Fr.311 |  |

Stephen Decatur |

|

| $20 | 1886 | Fr.316 |  |

Daniel Manning | |

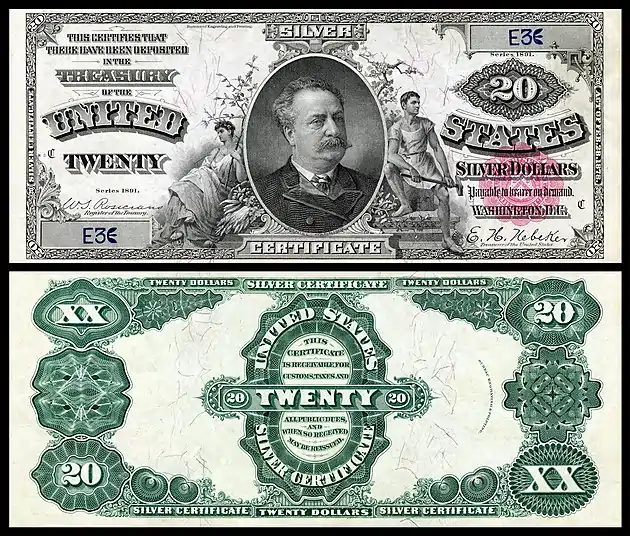

| $20 | 1891 | Fr.317 |  |

Daniel Manning | |

| $50 | 1878 | Fr.324 |  |

Edward Everett |

|

| $50 | 1880 | Fr.327 |  |

Edward Everett | |

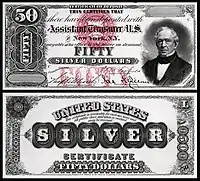

| $50 | 1891 | Fr.331 |  |

Edward Everett | |

| $100 | 1878 | Fr.337b |  |

James Monroe |

|

| $100 | 1880 | Fr.340 |  |

James Monroe | |

| $100 | 1891 | Fr.344 |  |

James Monroe | |

| $500 | 1878 | Fr.345a |  |

Charles Sumner | 345a – Scofield and Gilfillan, CS by A.U. Wyman* – large red, rays |

| $500 | 1880 | Fr.345c |  |

Charles Sumner | |

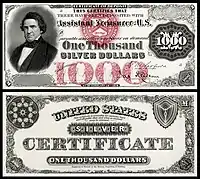

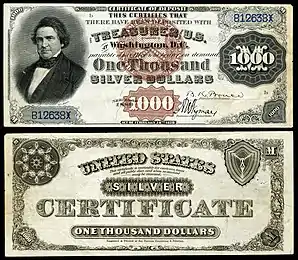

| $1,000 | 1878 | Fr.346a |  |

William Marcy | 346a – Scofield and Gilfillan, CS unknown – large red, rays |

| $1,000 | 1880 | Fr.346d |  |

William Marcy | |

| $1,000 | 1891 | Fr.346e |  |

William Marcy | 346e – Tillman and Morgan – small red |

Small-size United States silver certificates (1928–1957)

| Value | Series | Fr.[nb 9] | Image | Portrait | Signature & seal varieties |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

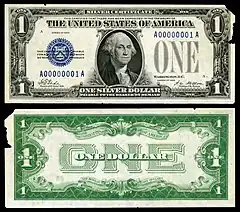

| $1 | 1928 to 1928-E | Fr.1600 |  |

George Washington | 1600 – Tate and Mellon (1928) – blue |

1601 – Woods and Mellon (1928A) – blue[nb 10] | 1602 – Woods and Mills (1928B) – blue | 1603 – Woods and Woodin (1928C) – blue | 1604 – Julian and Woodin (1928D) – blue | 1605 – Julian and Morgenthau (1928E) – blue |

| $1 | 1934 | Fr.1606 |  |

George Washington | 1606 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934) – blue |

| $1 | 1935 to 1935-G | Fr.1607 |  |

George Washington | 1607 – Julian and Morgenthau (1935) – blue |

1608 – Julian and Morgenthau (1935A)– blue | 1609 – Julian and Morgenthau (1935A) R-Exp – blue.[nb 11] | 1610 – Julian and Morgenthau (1935A) S-Exp – blue | 1611 – Julian and Vinson (1935B) – blue | 1612 – Julian and Snyder (1935C) – blue | 1613W – Clark and Snyder (1935D) Wide – blue[nb 12] | 1613N – Clark and Snyder (1935D) Narrow – blue | 1614 – Priest and Humphrey (1935E) – blue | 1615 – Priest and Anderson (1935F) – blue | 1616 – Smith and Dillon (1935G) – blue |

| $1 | 1935-G to 1957-B | Fr.1619 |  |

George Washington | 1617 – Smith and Dillon (1935G) – blue[nb 13] |

1618 – Granahan and Dillon (1935H) – blue | 1619 – Priest and Anderson (1957) – blue | 1620 – Smith and Dillon (1957A) – blue | 1621 – Granahan and Dillon (1957B) – blue |

| $5 | 1934 to 1934-D | Fr.1650 |  |

Abraham Lincoln | 1650 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934) – blue |

1651 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934A) – blue | 1652 – Julian and Vinson (1934B) – blue | 1653 – Julian and Snyder (1934C) – blue | 1654 – Clark and Snyder (1934D) – blue |

| $5 | 1953 to 1953-C | Fr.1655 |  |

Abraham Lincoln | 1655 – Priest and Humphrey (1953) – blue |

1656 – Priest and Anderson (1953A) – blue | 1657 – Smith and Dillon (1953B) – blue | 1658 – Granahan and Dillon (1953C) – blue[nb 14] |

| $10 | 1933 to 1933-A | Fr.1700 |  |

Alexander Hamilton | 1700 – Julian and Woodin (1933) – blue[nb 15]

1700a – Julian and Morgenthau (1933A) – blue[nb 14] |

| $10 | 1934 to 1934-D | Fr.1701 |  |

Alexander Hamilton | 1701 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934) – blue |

1702 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934A) – blue | 1703 – Julian and Vinson (1934B) – blue | 1704 – Julian and Snyder (1934C) – blue | 1705 – Clark and Snyder (1934D) – blue |

| $10 | 1953 to 1953-B | Fr.1706 |  |

Alexander Hamilton | 1706 – Priest and Humphrey (1953) – blue |

1707 – Priest and Anderson (1953A) – blue | 1708 – Smith and Dillon (1953B) – blue |

| $1 | 1935-A | Fr.2300 |  |

George Washington | 2300 – Julian and Morgenthau – brown |

| $1 | 1935-A | Fr.2306 |  |

George Washington | 2306 – Julian and Morgenthau (1935A) – yellow |

| $5 | 1934-A | Fr.2307 |  |

Abraham Lincoln | 2307 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934A) – yellow |

| $10 | 1934 to 1934-A | Fr.2309 |  |

Alexander Hamilton | 2308 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934) – yellow |

2309 – Julian and Morgenthau (1934A) – yellow |

See also

Explanatory footnotes

- ↑ Large size notes represent the earlier types or series of U.S. banknotes. Their "average" dimension is 7.375 × 3.125 inches (187 × 79 mm). Small size notes (described as such due to their size relative to the earlier large size notes) are an "average" 6.125 × 2.625 inches (156 × 67 mm), the size of modern U.S. currency. "Each measurement is +/- 0.08 inches (2mm) to account for margins and cutting".[3]

- ↑ Some have suggested that the bimetallic standard was actually initiated by Thomas Jefferson.[14]

- ↑ Although the exact monthly purchase was left to the discretion of the Secretary of the Treasury, the $2 million minimum was never exceeded.[23]

- ↑ "The act of February 28, 1878, also authorized the holder of these silver dollars to deposit: the same with the Treasurer, or any Assistant Treasurer, of the United States, in sums not less than ten dollars, and receive therefor certificates of not less than ten dollars each, corresponding with the denominations of the United States notes."[24]

- ↑ "SEC. 2. The Secretary of the Treasury shall maintain the ownership and the possession or control within the United States of an amount of silver of a monetary value equal to the face amount of all outstanding silver certificates. Unless the market price of silver exceeds its monetary value, the Secretary of the Treasury shall not dispose of any silver held or owned by the United States in excess of that required to be held as reserves against outstanding silver certificates, but any such excess silver may be sold to other departments and agencies of the Government or used for the coinage of standard silver dollars and subsidiary silver coins. Silver certificates shall be exchangeable on demand at the Treasury of the United States for silver dollars or, at the option of the Secretary of the Treasury, at such places as he may designate, for silver bullion of a monetary value equal to the face amount of the certificates".[43]

- ↑ Notes issued under a given Series (e.g., Series 1880, Series 1899) are, in some cases, released over a period of years, as reflected in the Friedberg number signature and seal varieties. For example, based on dates of the signature combinations,[46] the Series 1899 $1 silver certificate was first issued with the signature combination of Lyons and Robert (in office together from 1898 to 1905) and last issued with the Speelman and White signatures (in office together from 1922 to 1927). Therefore, a Series 1899 note could have been issued as late as 1927.

- ↑ "Fr" numbers refer to the numbering system in the widely used Friedberg reference book. Fr. numbers indicate varieties existing within a larger type design.[48]

- ↑ Varieties are presented by Fr. number followed by the specific differences in signature combination, seal (color, size, and style), and minor design changes, if applicable. For Series 1878 notes, an asterisk following the Assistant Treasurer's name indicates it is hand-signed versus engraved.

- ↑ Because small-size silver certificates are presented in ascending Friedberg number, World War II emergency issue notes (2300, 2306, 2307, and 2309) are presented out of chronological order at the end of the table.

- ↑ Serial blocks of the 1928A and 1928B silver certificates that were lettered XB or YB were made of experimental paper, and ZB of regular paper as a control.[53]

- ↑ Series 1935A "Experimental" bills were stamped with either a red "R" or "S" while testing regular and synthetic papers.[8]

- ↑ For 1935D, narrow and wide refer to the width of design features on the reverse of the note. The wide variety is 0.0625 in (1.5875 mm) larger and has a four-digit reverse plate number less than 5016.[54]

- ↑ The motto ("In God We Trust") was added to the Series of 1935G notes midway through the issue.[8]

- 1 2 Printed but not issued.[55]

- ↑ Very few Series 1933 $10 Silver Certificates were released before they were replaced by Series 1934 and most of those remaining were consigned to destruction; only a few dozen are known to collectors today.[56]

Citations

- 1 2 3 4 "Silver Certificates". Bureau of Engraving and Printing/Treasury Website. Archived from the original on April 3, 2014. Retrieved February 12, 2014.

- 1 2 Leavens, p. 24.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 7.

- ↑ Blake, p. 18.

- 1 2 3 4 Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 74.

- 1 2 3 Knox, p. 155.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 185.

- 1 2 3 Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 187.

- ↑ Friedman, p. 1166.

- ↑ O'Leary, p. 392.

- 1 2 Barnett, p. 178.

- ↑ Friedman, p. 1165.

- ↑ Lee, p. 388.

- ↑ Carothers, p. 5.

- ↑ O'Leary, p. 388.

- ↑ Leavens, p. 36.

- ↑ Taussig, 1892, p. 11.

- ↑ Leavens, p. 38.

- ↑ Lee, p. 393.

- 1 2 Lee, p. 396.

- ↑ Agger, p. 262.

- 1 2 3 Knox, p. 153.

- ↑ Taussig, 1892, p. 8.

- ↑ Knox, p. 152.

- ↑ Taussig, 1892, p. 15.

- ↑ Taussig, 1892, p. 10.

- ↑ Taussig, 1892, p. 16.

- ↑ Champ & Thomson, p. 12.

- ↑ McVey, p. 438.

- ↑ Champ & Thomson, p. 14.

- 1 2 Leavens, p. 39.

- 1 2 Schwartz & Lindquist, p. 9.

- 1 2 3 4 "BEP History". Bureau of Engraving and Printing/ Treasury Website. Archived from the original on January 14, 2014. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ https://www.loc.gov/law/help/statutes-at-large/73rd-congress/session-2/c73s2ch674.pdf

- ↑ "Series of 1935 $1 Silver Certificate – Values and Pricing". Archived from the original on May 7, 2014.

- ↑ "USPaperMoney.Info: Delivery Dates by Series". www.uspapermoney.info.

- 1 2 Schwartz & Lindquist, p. 24.

- ↑ Cuhaj, p. 133.

- ↑ "A Guide To Values and Pricing for Star Notes". Archived from the original on November 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Dillon, p.401.

- 1 2 Ascher, p. 99.

- 1 2 Dillon, p.400.

- 1 2 3 Public Law 88-36 (An Act to repeal certain legislation relating to the purchase of silver, and for other purposes) (PDF) (Report). U.S. Government Printing Office. 1963. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- ↑ Grey, p. 83.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, pp. 70–90 and 188–90.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 303.

- ↑ Blake, p. 19.

- 1 2 Friedberg & Friedberg, pp. 6–7.

- ↑ Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances (Report). United States Department of the Treasury. 1892. p. 475. Retrieved February 16, 2014.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, pp. 74–81.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, pp. 70–90.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, pp. 188–90.

- ↑ Schwartz & Lindquist, p. 31.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 170.

- ↑ Friedberg & Friedberg, p. 190.

- ↑ Schwartz & Lindquist, p. 156.

General references

- Agger, Eugene E. (1918). "The Denominations of the Currency". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 32 (2): 257–277. doi:10.2307/1885428. JSTOR 1885428.

- Ascher, Leonard W. (1964). "The Coming Chaos in Our Coinage". Financial Analysts Journal. 20 (3): 99–102. doi:10.2469/faj.v20.n3.99. JSTOR 4469657.

- Barnett, Paul (1964). "The Crime of 1873 Re-examined". Agricultural History. 38 (3): 178–181. JSTOR 3740438.

- Blake, George Herbert (1908). United States paper money. George H. Blake. p. 32. Retrieved March 13, 2014.

- Carothers, Neil (1932). "A Senate Racket". The North American Review. 233 (1): 4–15. JSTOR 25113955.

- Cuhaj, George S. (2012). Standard Catalog of United States Paper Money. Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-4402-3087-5. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- Dillon, C. Douglas (1963). Annual Report of the Secretary of the Treasury on the State of the Finances (Report). United States Government Printing Office. pp. 400–403.

- Friedberg, Arthur L.; Friedberg, Ira S. (2013). Paper Money of the United States: A Complete Illustrated Guide With Valuations (20th ed.). Coin & Currency Institute. ISBN 978-0-87184-520-7. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- Friedman, Milton (1990). "The Crime of 1873". Journal of Political Economy. 98 (6): 1159–1194. doi:10.1086/261730. JSTOR 2937754. S2CID 153940661.

- Grey, George B. (2002). Federal Reserve System: Background, Analyses and Bibliography. Nova Science Publishers, Inc. ISBN 978-1-59033-053-1. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- Knox, John Jay (1888). United States Notes: A history of the various issues of paper money by the government of the United States (3rd ed.). Charles Scribner's Sons.

- Leavens, Dickson H. (1939). Silver Money. Principia Press, Inc. Retrieved February 13, 2014.

- Lee, Alfred E. (1886). "Bimetalism in the United States". Political Science Quarterly. 1 (3): 386–399. doi:10.2307/2139359. JSTOR 2139359.

- McVey, Frank L. (1902). "The Reclassification of the Paper Currency". Journal of Political Economy. 10 (3): 437–442. doi:10.1086/250857. JSTOR 1819565.

- O'Leary, Paul M. (1960). "The Scene of the Crime of 1873 Revisited: A Note". Journal of Political Economy. 68 (4): 388–392. doi:10.1086/258345. JSTOR 1830011. S2CID 153797690.

- Schwartz, John; Lindquist, Scott (2011). Standard Guide to Small-Size U.S. Paper Money – 1928 to Date. Krause Publications. ISBN 978-1-4402-1703-6. Retrieved February 14, 2014.

- Taussig, F.W. (1890). "The Silver Situation in the United States". The Quarterly Journal of Economics. 4 (3): 291–315. doi:10.2307/1881888. hdl:2027/uc1.$b245353. JSTOR 1881888.

- Taussig, F.W. (1892). "The Silver Situation in the United States". Publication of the American Economic Association. 7 (1): 7–118. JSTOR 2485709.

Further reading

- Hessler, Gene; Chambliss, Carlson (2006). The Comprehensive Catalog of U.S. Paper Money: All United States Federal Paper Money Since 1812 (7th ed.). BNR Press. ISBN 9780931960666.

- National Monetary Commission (1910). Laws of the United States concerning money, banking, and loans, 1778–1909. Government Printing Office. Retrieved February 14, 2014.