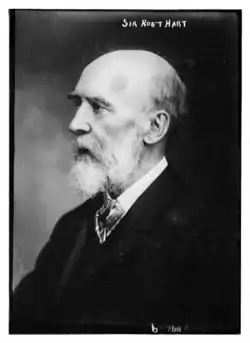

Sir Robert Hart | |

|---|---|

| |

| 2nd Inspector-General of the Chinese Maritime Customs Service | |

| In office 15 November 1863 – 20 September 1911 | |

| Monarchs | Tongzhi Emperor Guangxu Emperor Xuantong Emperor |

| Preceded by | Horatio Nelson Lay |

| Succeeded by | Francis Aglen |

| Personal details | |

| Born | Robert Walter Hart 20 February 1835 Portadown, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland |

| Died | 20 September 1911 (aged 76) Great Marlow, Buckinghamshire, England |

| Resting place | Bisham, Berkshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Alma mater | Queen's College, Belfast |

Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet, GCMG (20 February 1835 – 20 September 1911) was a British diplomat and official in the Qing Chinese government, serving as the second Inspector-General of China's Imperial Maritime Custom Service (IMCS) from 1863 to 1911. Beginning as a student interpreter in the consular service, he arrived in China at the age of 19 and resided there for 54 years, except for two short leaves in 1866 and 1874.[1]

Hart was the most important and most influential Westerner in Qing dynasty China.[2][3] According to Jung Chang, he transformed Chinese Customs "from an antiquated set-up, anarchical and prone to corruption, into a well-regulated modern organisation, which contributed enormously to China's economy."[4] Professor Rana Mitter of the University of Oxford writes that Hart "was honest and helped to generate a great deal of income for China."[5] Sun Yat-sen described him as "the most trusted as he was the most efficient and influential of 'Chinese.'"[6]

Early life and education

Hart was born in a little house in Dungannon Street, Portadown, County Armagh, Ulster, Ireland. He was the eldest of 12 children of Henry Hart (1806–1875), who worked in the distilleries, and a daughter of John Edgar of Ballybreagh. Hart's father was a "man of forceful and picturesque character, of a somewhat unique strain, and a Wesleyan to the core." At the age of 12, Hart's family moved to Milltown (near Maghery), on the banks of the Lough Neagh, staying there for a year before moving on to Hillsborough, where he first attended school. He was sent for a year to a Wesleyan school in Taunton, England, where he learnt his first Latin. His father's anger that his son was allowed to return home unaccompanied at the end of the school year led him being sent to the Wesleyan Connexion School in Dublin (now Wesley College Dublin) instead.[7]

Hart studied hard at school. By the age of 15, he was ready to leave school, and his parents decided to send him to the newly founded Queen's College, Belfast. He easily passed the entrance exams and earned himself a scholarship (he earned a further scholarship in the second year, and another in the third). He found little time for sports, but was heavily influenced by Ralph Waldo Emerson's Essays and had his first poem published in a Belfast newspaper. During his time at university, he became a favourite student of James McCosh, and they continued to correspond throughout the rest of their lives. In 1853, he took his degree examinations, and gained his B.A. at the age of 18. He also won medals in Literature as well as in Logic and Metaphysics, and left with the distinction of being a Senior Scholar. He decided to study for a master's degree but in spring 1854 was instead nominated by Queen's College for the Consular Service in China.[8][9]

Consular Service in China

Hart went down to the Foreign Office in London, where he met with the Permanent Under-Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, Edmund Hammond, and left for China in May 1854.[10] Hart took a ship from Southampton to Alexandria, then travelled to Suez, then on to Galle and Bombay, before arriving in Hong Kong. He spent three months as a student interpreter at the Superintendency of Trade, before the return of John Bowring, the Governor of Hong Kong. On Bowring's return, Hart was assigned to the British Consulate in Ningbo. In 1855, following a dispute with his Portuguese colleague, the British Consul was suspended, with Hart taking over his duties for a few months. Hart's calmness and good judgement in the face of conflict between the Chinese and Portuguese earned him favourable recommendations. Hart returned to his duties following the appointment of a new Consul, and was still resident in Ningbo (Ningpo) during the Ningpo massacre on 26 June 1857.[11]

In March 1858, Hart was transferred to Canton to serve as the Secretary of the Allied Commission that governed the city. In this role, he served under Harry Smith Parkes, and found the work "exceedingly interesting": Parkes often took Hart on his trips around or outside Canton. In October 1858, Hart was made an interpreter at the British Consulate in Canton under Rutherford Alcock. In 1859, the Chinese viceroy Lao Tsung Kuang, a special friend of Hart's, invited him to set up a customs house in Canton similar to the one in Shanghai under Horatio Nelson Lay. In response, Hart said that he knew nothing of customs, but wrote to Lay to explore the possibility. Lay then offered him the role of Deputy Commissioner of Customs, which he accepted, and Hart asked the British government if they would allow him to resign from the consular service. They permitted this, but made clear that he would not be allowed to return whenever he pleased: he submitted his resignation in May 1859, and joined the customs service.[12]

Chinese customs

Upon entering the customs service, Hart began drawing up a series of regulations for the operation of the customs house in Canton. For two years, from 1859 to 1861, Hart worked hard in Canton, but never fell ill in the hot and damp climate. In 1861, facing the threat of the Taiping Rebellion marching on Shanghai, Horatio Nelson Lay sought leave to return to Britain to nurse his injuries sustained during an anti-British riot in 1859. Lay claimed that so serious were his injuries that he was forced to return to England for two years to recover. In his place, two officiating Inspectors-General were appointed: George Henry Fitzroy, a former private secretary to Lord Elgin, and Hart. Whilst Fitzroy was content to stay in Shanghai, Hart went around China establishing new customs offices. With the recent ratification of the Treaty of Tientsin, a number of new ports were opened to foreign trade, and so new customs structures had to be put in place.[13] In 1861, Hart recommended to the Zongli Yamen the purchase of the Osborn or "Vampire" Fleet. When the proposal was adopted, Lay, on leave in Britain, set out arranging the purchase of the ships and hiring of personnel.

Inspector-General

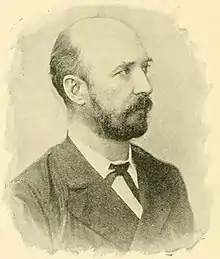

Hart as caricatured in Vanity Fair, December 1894

The good relations Hart established with the imperial authorities in Peking while deputising for Lay, and conflict between Lay and Prince Gong and the Zongli Yamen over the Osborn Fleet, led them to dismiss the difficult and haughty Lay upon his return from leave. Hart was appointed in his place in November 1863, with British approval. As Inspector-General of China's Imperial Maritime Custom Service (IMCS), Hart's main responsibilities included collecting custom duties for the Chinese government, as well as expanding the new system to more sea and river ports and some inland frontiers, standardising its operations, and insisting on high standards of efficiency and honesty.[14] The top echelon of the service was recruited from all the nations trading with China. Hart's advice led to the improvement of China's port and navigation facilities.

From the start, Hart was anxious to use such influence as he possessed in favour of other modernising steps. In October 1865 Hart submitted to Prince Gong a memorandum which caused some offence at the time. In it he advised that "[o]f all the countries in the world, none is weaker than China" and outlined his proposals.[15] A modern postal service and the supervision of internal taxes on trade were eventually added to the Service's responsibilities. Hart worked to persuade China to establish its own embassies in foreign countries. Earlier, in 1862, he had with the Manchu noble Prince Gong established the Tongwen Guan (School of Combined Learning) in Peking, with a branch in Canton, to enable educated Chinese to learn foreign languages, culture and science, for China's future diplomatic and other needs. (An early appointment to the school was the completely unsuitable 'Baron von Gumpach' (an assumed name) whose discharge led him to sue Hart in the British Supreme Court for China and Japan for defamation. In 1873, the case ultimately went to the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council Hart v Gumpach[16] which upheld Hart's right to make the decision.[17]) In 1902 the Tongwen Guan was absorbed into the Imperial University, now Peking University.

Hart was known for his diplomatic skills, and befriended many Chinese and Western officials. This aided him in directing customs operations without interruption even during periods of turmoil. His American Commissioner, Edward Drew, credited him with preventing a war with Britain in 1876 (via the Chefoo Convention), and he and his London representative, James Campbell, helped bring about peace after a French attack on the Chinese navy in Fuzhou in 1884. In 1885, Hart had also been asked to become Minister Plenipotentiary at Peking, upon the retirement of Sir Thomas Wade. He declined the honor after four months of hesitation, on the grounds that his work in the Customs Service was of certain benefit to both China and Britain, but that the outcome of a change of post was unclear.[18] In 1885, Hart wrote a letter to Lord Salisbury, strongly advocating an alliance with China as a preemptive defence of British India from the Russian Empire.[19]

During Hart's tenure in the Maritime Customs, Prince Gong was head of the Zongli Yamen, the newly established Chinese equivalent of the British Foreign Office, and the two men held each other in high regard. Hart was so well known in the Zongli Yamen that he was affectionately nicknamed "our Hart" (wǒmen de Hèdé, 我們的赫德). He also often worked closely with the powerful Viceroy, Li Hongzhang and their final work together involved negotiating a settlement China could tolerate at the end of the Boxer Rebellion, when the Eight-Nation Alliance of Western forces took control of Peking to lift the Siege of the International Legations, after the Dowager Empress and her nephew the Guangxu Emperor had fled the city.

Hart held his post till his retirement in 1910, although he left China on leave in April 1908, and was succeeded temporarily by his brother-in-law, Sir Robert Bredon, and then formally by Sir Francis Aglen. Hart died on 20 September 1911 after a cardiac decline following a bout of pneumonia. He was buried on 25 September 1911 at Bisham, Berkshire, England.[9] His tombstone was restored in 2013.[20]

Personal life

In China, Hart purchased women for sex in order to always "have a girl in the room with me, to fondle when I please".[21]: 35 In October 1854, Hart noted following his purchase of a teenage sex servant that "some of the China women are very good-looking: you can make one your absolute possession for 50 to 100 dollars and support her at a cost of only 2 or 3 dollars per month."[21]: 35 His purchase of Chinese sex workers occurred over a 20 year period.[21]: 211

Hart fathered three children with a Chinese sex servant.[21]: 211 He returned to England to configure a family with 18-year-old Hester Bredon.[21]: 211 They married in Dublin on 22 August and in September left for Peking.[22] Bredon lived with Hart in China and the two had children together.[21]: 211 After a decade, Bredon took the children she had with Hart and returned to England.[21]: 211 Hart resumed his purchases of Chinese sex workers for a time.[21]: 211 In 1883, Hart began living celibately.[21]: 211

Hart was disappointed in the adult lives of his three legitimate children, but acknowledged in a letter to Campbell that he had been a neglectful father, not being present to set an example, but China was his priority.[23]

His diary records letters from her in 1870 and in May 1872 "Will this never end?".[24] While making no direct contact with them, Hart took an interest in the progress of his children with his sex servant, through his lawyer and soon also via Campbell, his friend and colleague in charge of the London office.[25] In his last decade, he was obliged to acknowledge them by legal declarations.[26]

He had deep friendships with many girls and women, amongst whom were three generations of the Carrall family.[23]

Many of his male staff felt he was a supportive friend as well as a demanding superior.[27]

Archives

The papers and correspondence of Sir Robert Hart (MS 15) are held in the Special Collections & Archives of Queen's University, Belfast[28][29] and at (PP MS 67) in the Archives and Special Collections of the School of Oriental and African Studies, London.[30]

Awards and recognition

Robert Hart, was highly decorated, receiving four hereditary titles, fifteen orders of knighthood (of the first class) and many other honorary academic and civic awards.

His skills as Inspector-General were recognized by both Chinese and Western authorities, and he was awarded several honorific Chinese titles, including the Red Button, or button of the highest rank; a Peacock's Feather; the Order of the Double Dragon; the Ancestral Rank of the First Class of the First Order for Three Generations; and the title of Junior Guardian of the Heir Apparent in December 1901.[31] He was also appointed a CMG, KCMG, and GCMG, and received a British baronetcy. In 1900, he was awarded the Prussian Order of the Crown (First Class), and received this in person the following year from the German Minister in China.[32] In 1906, he was awarded a Grand Cross of the Order of the Dannebrog by the King of Denmark.

His name is still remembered through a street, Hart Avenue, in Tsim Sha Tsui, Hong Kong. There was also formerly a "Rue Hart " in the Beijing Legation Quarter[33] (now Taijichang First Street) and a Hart Road in Shanghai (now Changde Road).

In 1935, the "Sir Robert Hart Memorial Primary School" in Portadown, Northern Ireland, was established in his name.[34]

Hart is commemorated in the scientific name of a species of Chinese legless lizard, Dopasia harti.[35]

He was posthumously promoted to "Minister" rank and awarded the title of Senior Guardian of the Heir Apparent according to Chinese political tradition.

Honours list

1870: Chevalier of the Order of Vasa (Sweden).

1870: Chevalier of the Order of Vasa (Sweden). 1873: Grand Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph (Austria-Hungary; Commander: 1870)

1873: Grand Cross of the Order of Franz Joseph (Austria-Hungary; Commander: 1870) 1875: Honorary Master of Arts, Queen's College, Belfast.

1875: Honorary Master of Arts, Queen's College, Belfast..svg.png.webp) 1881: Red Button of the First Class (China).

1881: Red Button of the First Class (China). 1882: Honorary Doctor of Laws, Queen's College, Belfast.

1882: Honorary Doctor of Laws, Queen's College, Belfast. 1885: Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France; Commander: 1878)

1885: Grand Officer of the Legion of Honour (France; Commander: 1878).svg.png.webp) 1885: First Class, Second Grade of the Order of the Double Dragon (China)

1885: First Class, Second Grade of the Order of the Double Dragon (China).svg.png.webp) 1885: The Peacock's Feather (China)

1885: The Peacock's Feather (China) 1885: Knight Commander of the Order of Pius IX (Holy See).

1885: Knight Commander of the Order of Pius IX (Holy See)..svg.png.webp) 1886: Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Michigan.

1886: Honorary Doctor of Laws, University of Michigan. 1888: Grand Cross of the Order of Christ (Portugal).

1888: Grand Cross of the Order of Christ (Portugal). 1889: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (Great Britain; KCMG: 1882; CMG: 1879)

1889: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of St Michael and St George (Great Britain; KCMG: 1882; CMG: 1879).svg.png.webp) 1889: Ancestral rank of the First Class of the First order for three generations (China).

1889: Ancestral rank of the First Class of the First order for three generations (China). 1893: Baronet of Kilmoriarty in the County of Armagh.

1893: Baronet of Kilmoriarty in the County of Armagh._-_Commander_Grand_Cross.svg.png.webp) 1894: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star (Sweden).

1894: Commander Grand Cross of the Order of the Polar Star (Sweden). 1897: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Orange Nassau (Netherlands).

1897: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of Orange Nassau (Netherlands). 1900: First Class of the Order of the Crown (Prussia).

1900: First Class of the Order of the Crown (Prussia)..svg.png.webp) 1901: Junior Guardian of the Heir Apparent (China)

1901: Junior Guardian of the Heir Apparent (China) 1906: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown (Italy; Grand Officer: 1884).

1906: Knight Grand Cross of the Order of the Crown (Italy; Grand Officer: 1884). 1906: First Class of the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan).

1906: First Class of the Order of the Rising Sun (Japan). 1906: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium; Grand Officer: 1893; Commander: 1869)

1906: Grand Cordon of the Order of Leopold (Belgium; Grand Officer: 1893; Commander: 1869) 1907: First Class of the Order of St Anna (Russia).

1907: First Class of the Order of St Anna (Russia)._GC_ribbon.svg.png.webp) 1907: Grand Cross of the Order of the Dragon of Annam (France).

1907: Grand Cross of the Order of the Dragon of Annam (France). 1907: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav (Norway).

1907: Grand Cross of the Order of St. Olav (Norway).

Arms

|

See also

- History of foreign relations of China

- Ernest Mason Satow, who met Hart many times while he was British Minister in China, 1900–1906. (See Satow's diary).

References

- ↑ King, Frank H. H.. "Hart, Sir Robert, first baronet". Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (2004 ed.). Oxford University Press. doi:10.1093/ref:odnb/33739.

- ↑ Thompson, Larry Clinton (2009). William Scott Ament and the Boxer Rebellion. McFarland. p. 37. ISBN 9780786440085.

- ↑ Heaver, Stuart (9 November 2013). "Affairs of Our Hart". South China Morning Post. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ↑ Chang, p. 78

- ↑ Mitter, Prof Rana (20 April 2018). "Five ways China's past has shaped its present". BBC News – via bbc.co.uk.

- ↑ Cantlie, James; Jones, C. Sheridan (1912). Sun Yat Sen and the Awakening of China. New York: Fleming H. Revell Company. p. 248.

- ↑ Bredon, pp. 9–14

- ↑ Bredon, pp. 14–24

- 1 2 Drew, Edward B. (July 1913). "Sir Robert Hart and His Life Work in China". Journal of Race Development. 4 (1): 1–33. doi:10.2307/29737977. JSTOR 29737977.

- ↑ Bredon, pp. 24–5

- ↑ Bredon, pp. 31–42

- ↑ Bredon, pp. 42–52

- ↑ Bredon, pp. 55–60

- ↑ E.B. Drew,1913

- ↑ Jung Chang, 'Empress Dowager Cixi', Vintage Books, London 2013 pg. 80

- ↑ "Hart v Van Gumpach (China and Japan) [1873] UKPC 9 (28 January 1873)".

- ↑ Fairbank et al, comment pp. 14–15 and several of his contemporary letters to Campbell

- ↑ Fairbank et al, 1975, letters to Campbell, many letters between 519 and 559. Letter 550 includes his letter of explanation to Lord Granville

- ↑ Scott, David (2008). China and the international system, 1840-1949 : power, presence, and perceptions in a century of humiliation. Albany, NY: State University of New York Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-1-4356-9559-7. OCLC 299175689.

- ↑ "Remembering Sir Robert Hart | British Inter-University China Centre".

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Driscoll, Mark W. (2020). The Whites are Enemies of Heaven: Climate Caucasianism and Asian Ecological Protection. Durham: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-1-4780-1121-7.

- ↑ Smith R.J. et al, 1978

- 1 2 Tiffen 2012

- ↑ Smith et al 1991

- ↑ Fairbank et.al

- ↑ Li and Wildy,2003

- ↑ 70th birthday tribute, Queen's University Belfast Hart archive, MS15.8,J.

- ↑ "Special Collections – Information Services – Queen's University Belfast". 18 May 2016.

- ↑ Edward LeFevour, "A Report on the Robert Hart Papers at Queen's University, Belfast NI." Journal of Asian Studies 33.3 (1974): 437–439 online.

- ↑ "SOAS University of London". soas.ac.uk.

- ↑ "Latest intelligence -China". The Times. No. 36637. London. 13 December 1901. p. 3.

- ↑ "Court Circular". The Times. No. 36400. London. 12 March 1901. p. 10.

- ↑ Rue Hart. drben.net.

- ↑ "Hart Memorial Primary School". Retrieved 29 September 2014.

- ↑ Beolens, Bo; Watkins, Michael; Grayson, Michael (2011). The Eponym Dictionary of Reptiles. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. xiii + 296 pp. ISBN 978-1-4214-0135-5. (Hart, p. 117).

- ↑ "Grants and Confirmations of Arms, Vol. H". National Library of Ireland. p. 287. Retrieved 19 August 2022.

- ↑ Burke's Peerage. 1949.

Further reading

- Bell, S. Hart of Lisburn. Lisburn Historical Press, 1985.

- Bickers, Robert. "Revisiting the Chinese maritime customs service, 1854–1950." Journal of Imperial and Commonwealth History 36.2 (2008): 221–226.

- Bickers, Robert. "Purloined Letters: History and the Chinese Maritime Customs Service." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 691–723. online

- Bickers, Robert A. (2011). The scramble for China: foreign devils in the Qing empire, 1800–1914. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 9780713997491.

- Bredon, Juliet. Sir Robert Hart: The Romance of a Great Career (1st ed.). London: Hutchinson & Co., 1909.

- Bredon, Juliet. Sir Robert Hart: The Romance of a Great Career (2nd ed.). London: Hutchinson & Co., 1910.

- Broomhall A. J., Hudson Taylor & China's Open Century Volume Three: If I Had a Thousand Lives; Hodder and Stoughton and Overseas Missionary Fellowship, 1982.

- Brunero, Donna Maree. Britain's Imperial Cornerstone in China: The Chinese Maritime Customs Service, 1854–1949 (Routledge, 2006).

- Chang, Jung. Empress Dowager Cixi: The Concubine Who Launched Modern China. Vintage Books, 2014.

- Chang, Chihyun. "Sir Robert Hart and the Writing of Modern Chinese History." International Journal of Asian Studies 17.2 (2020): 109–126.

- Drew, Edward B. "Sir Robert Hart and His Life Work in China." The Journal of Race Development (1913): 1–33 online.

- Eberhard-Bréard, Andrea. "Robert Hart and China's statistical revolution." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 605–629. online

- Horowitz, Richard S. "Politics, power and the Chinese maritime customs: The Qing restoration and the ascent of Robert Hart." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 549–581 online.

- King, Frank H.H. "The Boxer Indemnity—'Nothing but Bad'." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 663–689.

- Li, L. and Wildy, D. "A New Discovery and its Significance: The Statutory Declarations made by Sir Robert Hart concerning his Secret Domestic Life in 19th century China," Journal of the Hong Kong Branch of the Royal Asiatic Society, 13. 2003.

- Morse, Hosea Ballou. International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Submission: 1861–1893. (1918) online; based in part on Hart's papers

- Morse, Hosea Ballou. International Relations of the Chinese Empire: The Period of Subjection: 1894–1911 (1918) online; based in part on Hart's papers.

- O'Leary, Richard. "Robert Hart in China: The significance of his Irish roots." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 583–604. online

- Spence, Jonathan D. To Change China: Western Advisers in China, 1620–1960. Harmondsworth and New York: Penguin Books, 1980.

- Tiffen, Mary, Friends of Sir Robert Hart: Three Generations of Carrall women in China. Tiffania Books, 2012.

- Van de Ven, Hans. "Robert Hart and Gustav Detring during the Boxer Rebellion." Modern Asian Studies 40.3 (2006): 631–662 online.

- Vynckier, Henk and Chihyun Chang, "'Imperium in Imperio': Robert Hart, the Chinese Maritime Customs Service, and its (Self-)Representations," Biography 37#1 (2014), pp. 69–92 online

- Wright, S.F. Hart and the Chinese Customs, William Mullen and Son for Queen's University, Belfast, 1952; a scholarly biography.

Primary sources

- Bruner, K. F., Fairbank, J. K., and Smith, R. J. Entering China's Service: Robert Hart's Journals, 1854–1863. Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1986.

- Fairbank J. K., Bruner, K. F., Matheson, E. M., ed. The I.G. in Peking: Letters of Robert Hart, Chinese Maritime Customs, 1868–1907. (2 vol. Belknap Press of Harvard University Press, 1975) vol 2 online

- Smith, R. J., Fairbank, J. K., & Bruner, K. F. Robert Hart and China's Early Modernization: His Journals, 1863–66. Council on East Asian Studies, Harvard University, 1991.

- Smith, Richard, John K. Fairbank, and Katherine Bruner, eds. Robert Hart and China’s Early Modernization: His Journals, 1863–1866 (BRILL, 2020).

External links

- The Irish Contribution to Joseon Korea – OhmyNews International Archived 16 February 2010 at the Wayback Machine at English.ohmynews.com

- Sir Robert Hart Collection at Queen's University, Belfast

- Chinese Maritime Customs project at the University of Bristol

- Sir Robert Hart Memorial Primary School

- Sir Robert Hart at Bumali Broject

- tiffaniabooks.com Archived 9 May 2021 at the Wayback Machine

- Newspaper clippings about Sir Robert Hart, 1st Baronet in the 20th Century Press Archives of the ZBW