The soils of the Kola Tembien woreda (district) in Tigray (Ethiopia) reflect its longstanding agricultural history, highly seasonal rainfall regime, relatively high temperatures, overall dominance of sandstone and metamorphic lithology and steep slopes.[1]

Factors contributing to soil diversity

Climate

Annual rainfall depth is very variable from year to year, but also from place to place. Whereas, there is around 500 mm annual rainfall near Tekezé River, this increases to 1600 mm in Abiy Addi, which benefits from the orographic rains induced by the Dogu’a Tembien massif.[2] Most rains fall during the main rainy season, which typically extends from June to September. Mean temperature in woreda town Abiy Addi is 22.4 °C, oscillating between average daily minimum of 12.8 °C and maximum of 31.5 °C. The contrasts between day and night air temperatures are much larger than seasonal contrasts.[3]

Geology

From the higher to the lower locations, the following geological formations are present:[4]

Topography

As part of the Ethiopian highlands the land has undergone a rapid tectonic uplift, leading the occurrence of mountain peaks, plateaus, valleys and gorges.

Land use

Generally speaking the level lands and intermediate slopes are occupied by cropland, while there is rangeland and shrubs on the steeper slopes. Remnant forests occur around Orthodox Christian churches and a few inaccessible places. A recent trend is the widespread planting of eucalyptus trees.

Environmental changes

Soil degradation in this district became important when humans started deforestation almost 5000 years ago.[5][6] Depending on land use history, locations have been exposed in varying degrees to such land degradation.

Geomorphic regions and soil units

Detailed information on soils is available for the southern part of the district which is part of the Giba River catchment. Given the complex geology and topography of the district, it has been organised into land systems - areas with specific and unique geomorphic and geological characteristics, characterised by a particular soil distribution along the soil catena.[7][8][9] Soil types are classified in line with World Reference Base for Soil Resources and reference made to main characteristics that can be observed in the field.

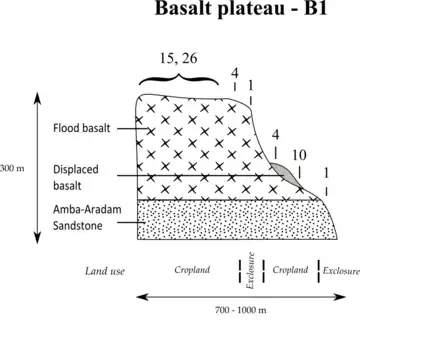

Basalt plateaus

- Associated soil types

- Inclusions

Adigrat Sandstone cliff and footslope

- Associated soil types

- Inclusions

- shallow, dry soils with very high amounts of stones (Leptic and Skeletic Cambisol and Regosol) (4)

- deep, dark cracking clays with good fertility, but problems of waterlogging (Chromic and Pellic Vertisol) (12)

- soils with stagnating water due to an abrupt textural change such as sand over clay (Haplic Planosol]]) (34)

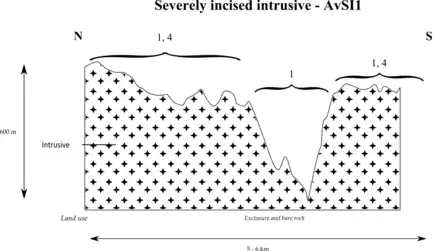

Severely incised granite near Giba mouth

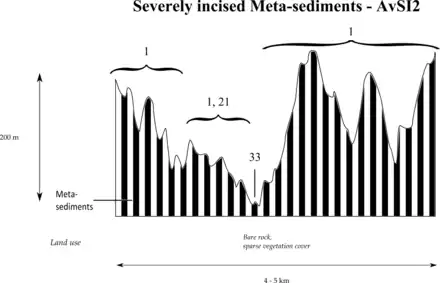

Severely incised metamorphic sedimentary rock

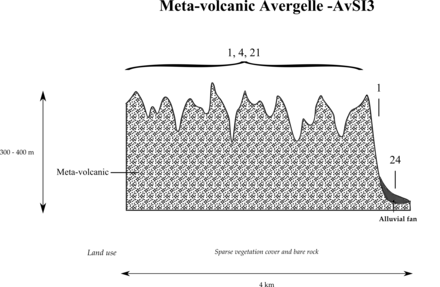

Soils on metamorphic volcanic rock

Soil erosion and conservation

The reduced soil protection by vegetation cover, combined with steep slopes and erosive rainfall has led to excessive soil erosion.[5][10][11] Nutrients and organic matter were lost and soil depth was reduced. Hence, soil erosion is an important problem, which results in low crop yields and biomass production. As a response to the strong degradation and thanks to the hard labour of many people in the villages, soil conservation has been carried out on a large scale since the 1980s and especially 1980s; this has curbed rates of soil loss.[12][13] Measures include the construction of infiltration trenches, stone bunds,[14] check dams,[15] small reservoirs such as Addi Asme'e as well as a major biological measure: exclosures in order to allow forest regeneration.[16]

References

- ↑ Nyssen, Jan; Tielens, Sander; Gebreyohannes, Tesfamichael; Araya, Tigist; Teka, Kassa; Van De Wauw, Johan; Degeyndt, Karen; Descheemaeker, Katrien; Amare, Kassa; Haile, Mitiku; Zenebe, Amanuel; Munro, Neil; Walraevens, Kristine; Kindeya Gebrehiwot; Poesen, Jean; Frankl, Amaury; Tsegay, Alemtsehay; Deckers, Jozef (2019). "Understanding spatial patterns of soils for sustainable agriculture in northern Ethiopia's tropical mountains". PLOS ONE. 14 (10): e0224041. Bibcode:2019PLoSO..1424041N. doi:10.1371/journal.pone.0224041. PMC 6804989. PMID 31639144.

- ↑ Jacob, M. and colleagues (2013). "Assessing spatio-temporal rainfall variability in a tropical mountain area (Ethiopia) using NOAAs Rainfall Estimates". International Journal of Remote Sensing. 34 (23): 8305–8321. Bibcode:2013IJRS...34.8319J. doi:10.1080/01431161.2013.837230. hdl:1854/LU-4252226. S2CID 140560276.

- ↑ Jacob, M. and colleagues (2019). "Dogu'a Tembien's Tropical Mountain Climate". Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains. GeoGuide. SpringerNature. pp. 45–61. doi:10.1007/978-3-030-04955-3_3. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6. S2CID 199105560.

- ↑ Sembroni, A.; Molin, P.; Dramis, F. (2019). Regional geology of the Dogu'a Tembien massif. In: Geo-trekking in Ethiopia's Tropical Mountains — The Dogu'a Tembien District. SpringerNature. ISBN 978-3-030-04954-6.

- 1 2 Nyssen, Jan; Poesen, Jean; Moeyersons, Jan; Deckers, Jozef; Haile, Mitiku; Lang, Andreas (2004). "Human impact on the environment in the Ethiopian and Eritrean highlands - a state of the art". Earth-Science Reviews. 64 (3–4): 273–320. Bibcode:2004ESRv...64..273N. doi:10.1016/S0012-8252(03)00078-3.

- ↑ Blond, N. and colleagues (2018). "Terrasses alluviales et terrasses agricoles. Première approche des comblements sédimentaires et de leurs aménagements agricoles depuis 5000 av. n. è. à Wakarida (Éthiopie)" (PDF). Géomorphologie: Relief, Processus, Environnement. 24 (3): 277–300. doi:10.4000/geomorphologie.12258. S2CID 134513245.

- ↑ Bui, E.N. (2004). "Soil survey as a knowledge system". Geoderma. 120 (1–2): 17–26. Bibcode:2004Geode.120...17B. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2003.07.006.

- ↑ "Principes de la cartographie des pédopaysages dans les Alpes". Écologie. 29 (1–2): 49. 1998. ProQuest 223074690.

- ↑ Tielens, Sander (2012). Towards a soil map of the Geba catchment using benchmark soils. MSc thesis. Leuven, Belgium: K.U.Leuven.

- ↑ Demel Teketay (2001). "Deforestation, wood famine, and environmental degradation in Ethiopia's highland ecosystems: urgent need for action". Northeast African Studies. 8 (1): 53–76. doi:10.1353/nas.2005.0020. JSTOR 41931355. S2CID 145550500.

- ↑ Nyssen, Jan; Frankl, Amaury; Zenebe, Amanuel; Deckers, Jozef; Poesen, Jean (2015). "Land management in the northern Ethiopian highlands: local and global perspectives; past, present and future". Land Degradation & Development. 26 (7): 759–794. doi:10.1002/ldr.2336. S2CID 129501591.

- ↑ Haftu Etsay, and colleagues (2019). "Factors that influence the implementation of sustainable land management practices by rural households in Tigrai region, Ethiopia". Ecological Processes. 8 (1). doi:10.1186/s13717-019-0166-8.

- ↑ Tibebu Kassawmar, and colleagues (2018). "Assessing the soil erosion control efficiency of land management practices implemented through free community labor mobilization in Ethiopia". ISWCR. 6 (2): 87–98.

- ↑ Nyssen, Jan; Poesen, Jean; Gebremichael, Desta; Vancampenhout, Karen; d'Aes, Margo; Yihdego, Gebremedhin; Govers, Gerard; Leirs, Herwig; Moeyersons, Jan; Naudts, Jozef; Haregeweyn, Nigussie; Haile, Mitiku; Deckers, Jozef (2007). "Interdisciplinary on-site evaluation of stone bunds to control soil erosion on cropland in Northern Ethiopia". Soil and Tillage Research. 94 (1): 151–163. doi:10.1016/j.still.2006.07.011. hdl:1854/LU-378900.

- ↑ Nyssen, J.; Veyret-Picot, M.; Poesen, J.; Moeyersons, J.; Haile, Mitiku; Deckers, J.; Govers, G. (2004). "The effectiveness of loose rock check dams for gully control in Tigray, Northern Ethiopia". Soil Use and Management. 20: 55–64. doi:10.1111/j.1475-2743.2004.tb00337.x. S2CID 98547102.

- ↑ Descheemaeker, K. and colleagues (2006). "Sediment deposition and pedogenesis in exclosures in the Tigray Highlands, Ethiopia". Geoderma. 132 (3–4): 291–314. Bibcode:2006Geode.132..291D. doi:10.1016/j.geoderma.2005.04.027.