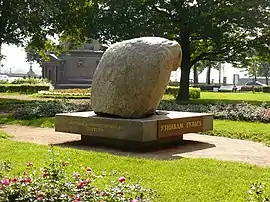

| The Solovetsky Stone | |

|---|---|

| A monument to the Victims of Political Repression, Russian: Соловецкий камень | |

| |

| Artist | Yuly Rybakov, Yevgeny Ukhnalyov |

| Completion date | 4 September 1990: Pedestal 4 September 2002: Solovki Stone |

| Medium | Granite |

| Movement | Minimalism |

| Dimensions | 225 cm × 230 cm × 235 cm (89 in × 91 in × 93 in) |

| Weight | 10,400 kg |

| Location | Saint Petersburg |

| 59°57′08″N 30°19′34″E / 59.952313°N 30.326125°E | |

The Solovetsky Stone is a monument to the victims of political repression in the Soviet Union and to those who have fought and fight for freedom. It stands in Troitskaya (Trinity) Square in Saint Petersburg, near several other buildings directly related to political repression in the Soviet era—the House of Tsarist Political Prisoners; the prison and necropolis of the Peter and Paul Fortress; and the Bolshoy Dom or headquarters of the NKVD, both in the city and the surrounding Leningrad Region. Nowadays, the Stone also serves as a focus for commemorative events and for gatherings related to current human rights issues.

The monument consists of a large boulder brought from the Solovetsky Islands in the White Sea, where the Solovki prison camp opened in 1923. The camp was the malignant cell which, in Solzhenitsyn's metaphor,[1] metastasized to create the entire Gulag network of forced labour camps. The Stone is a fitting symbol of the Gulag and the related practices of political terror. The Memorial society in Petersburg was behind the creation of the monument. It was designed by Yuly Rybakov and Yevgeny Ukhnalyov, both political prisoners during the Soviet period.

Design and symbolism

The monument comprises the Solovki Stone, a massive granite slab from the Solovetsky Islands, where the Solovki concentration camp operated in the 1920s and 1930s. The prison camp's diminutive name "Solovki" became shorthand in Russian for a punitive network of camps that already held more than 100,000 inmates in the 1920s. Between the 1930s and 1950, it has been estimated, the number of people who passed through the Gulag (as it later became known) reached 18 million, at least 1,500,000 of whom died in the camps.[2][3] The Gulag traumatized the population and had a lasting impact on several generations; it left its imprint on many aspects of society and culture.[4][5][6]

The granite slab was selected from among the boulders near the Savvatiyev Skethe (hermitage), which was used to house political prisoners in the 1920s. There on 19 December 1923, guards and a special firing squad shot and killed protesting prisoners.[7][8][9] The massacre marked a new stage in the repressive measures employed by the Soviet regime, and set an important precedent for resistance.[10][NB 1] Some sources assert that the stone was taken from Mount Sekirna, a hill in the vicinity of the Skethe. The Voznesensky Skethe (hermitage) on Mount Sekirna was used as a punishment block and execution yard.[11][12][13]

As an artefact from "that very place", keeping in touch with "the spirit of our ancestors", the Solovki Stone symbolizes a pre-Christian idea of continuity and the hereditivity of existence.[14][15][NB 2] In its designers conception, the stone's rough aesthetics endow it with a "backbone of personality that endures despite confronting faceless evil".[17]

The monument design is minimalist and it has a non-religious, secular character. It features a crude granite slab, 1.7 m (5 ft 7 in) high, mounted on a square granite pedestal (0.35 m × 2.35 m × 2.3 m [1 ft 2 in × 7 ft 9 in × 7 ft 7 in]), itself based on a concrete impost surrounded by granite footings.0.2 m (7.9 in) high.[18][19] The edges are oriented on the four cardinal points of the compass. From a certain angle, the stone resembles an elephant, which in Russian ('слон', 'slon') sounds like the abbreviation S.L.O.N. [Соловецкий лагерь особого назначения], the formal title of the "Solovetsky Special Purpose Camp".[20][21]

Inscriptions and location

The monument also conveys its meaning through the inscriptions on the pedestal.[15]

Its north face reads, "To the inmates of the Gulag" [Узникам ГУЛАГа]; the west face reads, "To those who fight for freedom" [Борцам за свободу]; and the east face reads "To the Victims of Communist Terror" [Жертвам коммунистического террора]. The south face carries words from Anna Akhmatova's long poem Requiem: "I would like to recall them all by name". The monument does not list any names, because not all the victims are yet known. Yuly Rybakov, one of the designers, consider the western insscription the most important because it commemorates not only the victims, but also all who have fought against the repressive system.[22][20][10] The lines on the east face explicitly name those responsible for the terror, a rare thing among similar monuments in Russia.[23] The direct mention of communism as the reason for this catastrophe, believes historian Alexander Etkind, makes the monument of universal significance.[24] The text on the Solovki Stone says nothing about its background. Its authors believe this should stir the interest of passers-by and make them curious to find out more.[10]

The monument is dedicated to all who were "shot, arrested, exiled, banned, broken by the Communist regime—whose graves are lost and fate unknown". The Memorial Society in St Petersburg, which initiated and sponsored the monument's creation, offered the following description of its significance: [25][26]

"This monument is a gift to the city on its 300th Anniversary from former political prisoners, who treasure freedom and human dignity more than personal safety and well-being. The Solovetsky Stone in Troitskaya Square is the symbol of free social thoughts, political and civic liberties. This monument pays tribute to all the victims of purposeless terror, it commemorates our fellow citizens, who suffered from political repression. It honors those who fought for human dignity among triumphant cruelty and didn't succumb to evil, preserving inner personal freedom and remained human in an inhuman world. This monument shows how a strong individual can overcome the totalitarian regime; it rejects violence and xenophobia. We live in an unstable country, which cannot guard our rights and freedom. So let this stone serve our freedom."

Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, Peter and Paul Fortress and Cathedral

Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, Peter and Paul Fortress and Cathedral Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, House of Tsarist Political Prisoners

Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, House of Tsarist Political Prisoners Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, Museum of Political History

Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, Museum of Political History Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, Trinity Chapel

Troitskaya Square: Solovetsky Stone, Trinity Chapel

The location of the Solovki Stone is itself significant.

The "Former Political Convicts" Residential Home (FPCRH) standing in front of the monument was built by the Soviet government in the early 1930s. It was intended for the revolutionaries and political activists, persecuted by the State police in Imperial Russia. Ironically, many inhabitants of the FPCRH fell victims of the Great Terror in 1937–1938. During the 1917 October Revolution the buildings of the Museum of Political History of Russia (St. Petersburg) to the north of Troitskaya square housed the Bolshevik authorities, who later headed the coup d'etat and initiated State Terror.[26] On the Field of Mars across the Neva there is a memorial necropolis, dedicated to the revolutionaries of 1917. This proximity is a vivid illustration, historian Zuzanna Bogumil believes, of the way in which "the revolution devours its children".[10] Across the Neva to the east is the Bolshoy Dom. The headquarters of the NKVD was built in the 1930s: today it houses its successor, the FSB.[15][NB 3] To the west, Troitskaya Square adjoins the Peter and Paul Fortress where, since Tsarist times, the Trubetskoy Bastion has been used as a political prison. After the revolution, the Soviet government incarcerated political prisoners here,[26] and it would later become the first location of the Great Terror.[28] A mass grave was discovered beneath the Golovkin Bastion of the fortress in 2007. It contained the bodies of victims of the Red Terror, perhaps even four of the Grand Dukes of Russia.[29] In 2003 the Holy Trinity Chapel was built northeast of the Solovki Stone, and marks the location of the Old Trinity Cathedral. The Cathedral was demolished in 1933 during the antireligious campaign of the Soviet Government.[26][NB 4]

The Trinity [Troitskaya] Square, furthermore, is the oldest administrative centre of St. Petersburg. Peter the Great, Zuzanna Bogumil reminds us, established the city and commanded that it develop, no matter what the human cost. Therefore, the Solovki Stone also epitomises the problem throughout Russian history of the inhuman treatment people have received.[10]

History

20th century—1961–1998

The idea of commemorating the victims of Soviet repression was first publicly proposed in October 1961 at the 22nd Congress of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union. When Nikita Khrushchev's program of De-Stalinisation ended in 1964, however, such a concept was abandoned and in the post-Khrushchev era political dissidents were once again repressed.[30] The idea persisted among Soviet dissidents during the 1970s.[31] In the 1980s, during perestroika, the policy of democratization and a relaxation of censorship finally allowed open discussions of the previously forbidden topic of State Terror.[32] At the end of the 1980s, the Memorial society was established. One of its major tasks was to commemorate the victims of political repression. At first it made a start only in Moscow, but after the St. Petersburg branch was founded in 1988 it became an active participant of the society's work.[33][34][35]

In June 1989 the Leningrad branch of the Memorial society called on citizens to create a monument in honour of the victims of political repression. As envisioned by the initiators, the monument should also be accompanied by a museum and an archive. Several locations were considered for the future monument: the Levashovo Memorial Cemetery; the Bolshoy Dom, NKVD (and KGB) headquarters in Leningrad; the Kresty Prison; and Troitskaya Square (then called Revolution Square) opposite the Former Political Convicts Residential Home. Memorial invited all citizens to join the discussion of the idea and initiated the fundraising campaign.[35]

On 27 March 1990, the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Congress of People's Deputies announced "an open competition on the best concept, location and design offer of a monument in honour of the victims of Stalin's terror". Troitskaya Square had been chosen as the preferred location.[36] Activists protested and demanded commemoration of all victims of Soviet repression. As a result, on 17 June 1992, the Leningrad City Congress cancelled the competition before it had begun.[25][37]

Memorial seized the initiative. Instead of the desired monument (which would require serious investments of time and money) a small, temporary sign would be created as a placeholder, the society announced.[10] On 4 September 1990, the last day of an "International Conference on Human Rights" in the city and on the eve of the memorial day for "Victims of the Red Terror" (5 September), a square granite base was installed on Trinity Square. "On this site a monument to the victims of political repression will one day stand," the inscription on its surface read. The base was crowned with a bronze wreath of barbed wire, and words from Akhmatova's Requiem ("I Would like to recall them all by name") were engraved on the south edge of the base.[20][35][38] it was designed by the artist Dmitry Bogomolov.[39]

The opening ceremony

The opening ceremony The opening ceremony

The opening ceremony At the memorial

At the memorial Overview

Overview

On 1 October 1990, the Leningrad authorities started a new round of the project competition in motion.

This time it considered the demand to widen the monument's message to "condemn all violence and illegality, neglection of political and any other intolerance" without reference to specific historical events.[37][40] The panel of judges was headed by two persons directly affected by the Red Terror: artist Andrei Mylnikov, whose father was executed in 1918, and art expert Dmitry Likhachov, a survivor of the Solovki camp. In spring 1991, the entries were displayed in the State Museum of the History of St. Petersburg. On 3 June 1991, the jury discussed them and selected the proposal of Dmitry Bogomolov which depicted a bronze human figure, crushed and crucified between four rocks. The lettering on the rocks was a record of political campaigns of repression in Petrograd-Leningrad. Soon the city administration lost interest, however, and the competition was cancelled.[35][41][42][43]

In 1995–1996 with the help from the Mayor of Saint Petersburg, Anatoly Sobchak, other memorials to the "victims of political repression" were unveiled in the city: Mihail Chemiakin's "Metaphysical Sphinxes" on the bank of the Neva opposite the Kresty Prison, and the "Moloch of Totalitarianism" by the entrance to the Levashovo Memorial Cemetery. Both were widely criticized by activists and former political prisoners: the message of the monuments was unclear, they said, so was the depiction of evil and violence.[44][45][46] In 1996, the municipal authorities announced that they would build a memorial monument based on the ideas of Edward Zaretsky,[47] a Leningrad-based sculptor and a member of local Jewish community. Zaretsky founded the Tsayar artistic association and went on to create such monuments as that to "Jews who fell victim to political repression" (1997) at the Levashovo Memorial Cemetery.[48][49] In 1998, Memorial's co-founder Veniamin Joffe publicly criticized the city administration for ignoring the future monument's location during the reburial ceremony of the remains of the last Romanovs, even though the procession passed through Troitskaya Square.[38]

For over ten years the city authorities back-pedalled over the proposal.[12][50] Memorial's wish for a grander monument vanished after the 1998 Russian financial crisis: many similar initiatives across the country then met the same fate.[10] In the late 1990s, the bronze wreath was stolen from the pedestal by vandals.[20][44][42]

21st century—2002

At the turn of the new millennium, Memorial renewed its efforts to create a monument. The socio-political climate in Russia was again hardly amenable: the country's new president Vladimir Putin was an officer of the KGB. Certain activists did not believe that the St Petersburg authorities would permit construction of the monument.[28] Veniamin Joffe decided, nevertheless, to follow the example of Arkhangelsk and Moscow and requested permission to install a boulder from the Solovki Archipelago.[10][15][20] After Joffe's untimely death in 2002 his widow Irina Flige took up the task.[42][50]

On behalf of Memorial she wrote to the city administration, formulating the main points of the future monument in her letter:

"The commemoration of the victims of political repression is inseparable from zero tolerance towards any form of ideological violence and political terror. There should be no features associated with evil and death about the monument, of tyranny over the human soul. The absolute political terror which arose throughout all our Soviet history resulted in the deaths of people of various confessions: Orthodox Christians, Muslims, practising Jews, Baptists, and even atheists. For that reason the monument should be non-sectarian. In light of the above, we consider a granite boulder from the Solovki Islands to be the best option, using the present square granite memorial base as a pedestal. The Solovki concentration camp symbolizes the Gulag in the history of our country. The Solovki Stone will become a decent memorial to those whom we lost to indiscriminate terror".[51]

In March 2001, the monument was included in the programme for the tercentenary celebrations of the founding of Saint Petersburg but received no budget allocation.[12][52]

Petersburg's Solovki Stone was designed by artists Yuly Rybakov and Yevgeny Ukhnalyov (the latter devised Russia's national coat of arms).[50] Both had suffered political repression during the Soviet period.[20][31] The monument was funded by donations, mostly from former political prisoners and their families. NGOs such as Memorial and Civil Control [grazhdanskaya kontrol], and the Union of Right Forces political party, made substantial contributions.[53][23][31][50] During their expedition to Solovki to select a suitable boulder Rybakov, Ukhnalyov and Flige found a massive granite slab near the former Savvatyev Skethe (hermitage). Transporting the hefty 10,400 kilograms [22,900 lb] boulder to St. Petersburg was a challenge but they were assisted by local fishermen and industrial workers and by the staff of the Solovki museum.[12][20][31]

Loading the stone

Loading the stone Loading the stone. Yuly Rybakov

Loading the stone. Yuly Rybakov Sailing off the Solovetsky Islands

Sailing off the Solovetsky Islands Installing the monument. Yuly Rybakov, Yevgeny Ukhnalyov

Installing the monument. Yuly Rybakov, Yevgeny Ukhnalyov After the installation: Yuly Rybakov, Irina Flige, Yevgeny Ukhnalyov

After the installation: Yuly Rybakov, Irina Flige, Yevgeny Ukhnalyov

The unhewn stone was successfully transported to St. Petersburg where on 4 September 2002 it was installed on the pedestal. Three more inscriptions were added around the four edges of the base.[21] It was 12 years to the day since the base was put in position.[20] The official inauguration took place on 30 October on the Day in Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repression, which coincided with the 300th Anniversary of St. Petersburg. City Governor Vladimir Yakovlev issued Decree No. 2572-pa, making the Solovki Stone city property[21][22] as of 15 October 2002.

Public activities and reactions

Every year on 5 September a ceremony remembering and mourning the loss of victims of "Political Repression and the Red Terror" in Soviet Russia takes place near the Solovki Stone. Among other annual demonstrations is "Restoring the Names", reading aloud the names of victims of political repression in Soviet Russia.[42][54] The Solovki Stone has also become a focus for public gatherings variously devoted to the victims of political terror, memorable dates in Russia's history, human rights initiatives and against violence and xenophobia.[55] Anna Politkovskaya,[56] Natalya Estemirova,[57][58] Stanislav Markelov and Anastasia Baburova,[59] Alexei Devotchenko,[60] Natalya Gorbanevskaya,[61] Valeriya Novodvorskaya,[62] Boris Nemtsov,[63] Vladimir Bukovsky, [64] and others have been commemorated here.

The first Saturday in June is a Day in Remembrance of the Victims of the Petrograd and Leningrad Prisons; it takes place near the Solovki Stone,[65] followed in early August by gatherings to mark the beginning of the Great Terror.[66] On 17 December, the anniversary of the enactment of Stalin's punitive 1933 law against gay people, LGBT activists lay floral tributes on the pedestal of the monument. There are usually protests each year on 20 December, the "Day of Secret Police Workers" [День работника органов безопасности Российской Федерации].[67] Gatherings in support of those charged in the Bolotnaya Square case, the Network case and other oppressed people have also been held here.[68][69]

The Solovki Stone in St. Petersburg has been vandalized several times. Within months of its inauguration it was daubed with swastikas and comments such as "not enough were killed", "slaves", etc.[70] The attacks were repeated in 2003,[71] 2007, 2012,[72] and 2013.[73] In 2013, for the first time, the issue of liability for the monument's condition was raised .[74] Finally Petersburg's ombudsman Alexander Shishlov demanded clarification of the monument's status.[75] In 2015 the traditional December Memorial Day was disturbed by people marching beneath portraits of Adolf Hitler. Neither the city administration or the local police intervened and human rights activists concluded that the march was a provocation staged by the city authorities.[76] In 2018 the Last Address civic initiative and the Solovetsky Stone were publicly criticized by nationalist Aleksandr Mokhnatkin.[77] On 30 October 2018, City Governor Alexander Beglov laid flowers at the monument.[78]

See also

- Butovo firing range, Moscow.

- Day in Remembrance of the Victims of Political Repression. Annual event in Russia (30 October) commemorating the Soviet era.

- Levashovo Memorial Cemetery, St. Petersburg.

- Mass graves in the Soviet Union

- political repression in the USSR

- Solovetsky Stone, Moscow.

References

- ↑ [ref to Gulag Archipelago].

- ↑ Werth, Nicolas (20 January 2009). "State Violence in Stalin's Time: An outline for an inventory and classification" (PDF). Stanford University.

- ↑ G. Zheleznov, Vinogradov, F. Belinskii (December 14, 1926). "Letter To the Presidium of the Central Executive Committee of the All-Union Communist Party (Bolshevik)". Library of Congress. Retrieved April 15, 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Applebaum 2012.

- ↑ Barnes 2011, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ Jakobson 1993, pp. 5–9.

- ↑ "A Memorial to Political Prisoners Shot at the Savvatiyev Skethe on 19 December 1923" [Памятный знак политзаключенным, расстрелянным в Савватиевском скиту] (in Russian). Sakharov Centre. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ↑ Andreeva, E. (5 September 2017). "The Scars borne by the Solovki Monastery from its days as a concentration camp" [Лагерные шрамы Соловецкого монастыря] (in Russian). TASS. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- ↑ Melgunov 2015, p. 270.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Bogumil, Z. (2010). "Crosses and Stones: Solovki symbols in constructing remembrance of the Gulag" [Кресты и камни: соловецкие символы в конструировании памяти о ГУЛАГе] (in Russian). NZ magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ Ezhelev, A. (2012). "Comment" [Прокомментируем] (in Russian). "Terra Incognita" human rights almanac. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Rubakov, Y. (2002). "Dedicated to the inmates of the Gulag" [Узникам ГУЛАГа посвящается…] (in Russian). Terra Incognita almanac. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ "In Memory of Political Prisoners held in the Solovki Skethes" [Памяти узников соловецких политскитов] (in Russian). Memorial Society. 15 August 2013. Retrieved 2020-05-19.

- ↑ Etkind, A. (9 August 2011). "Memorials to Grief and Stupidity" [Памятники горечи и глупости] (in Russian). Snob. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Etkind, A. (27 February 2017). "And their traces endure forever" [И след их вечен…] (in Russian). Hefter magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ Dorman, V. (2010). "From Solovki to Butovo: the Russian Orthodox Church and Memories of Repressive Measures in Post-Soviet Russia" [От Соловков до Бутово: Русская Православная Церковь и память о советских репрессиях в постсоветской России]. Laboratorium (in Russian) (2): 327–347. ISSN 2076-8214.

- ↑ "Memory of the quick and the dead" [Память – живая и мертвая] (in Russian). Novaya Gazeta. 27 March 2017. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ "The disagreement over the inscriptions on the Solovki Stone has been resolved" [Недоразумение с надписями на Соловецком камне исчерпано] (in Russian). St. Petersburg City Administration. 1 July 2019. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ Sakharov Center 2019.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "A Monument to the victims of Communist Terror has been unveiled in St. Petersburg" [Открытие памятника жертвам коммунистического террора в Санкт-Петербурге] (in Russian). Voice of America. 4 September 2002. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 3 Artemenko, M. (26 October 2018). "A tidal wave of Popular Grief as St. Petersburg honours the victims of Political Repression" ["Волга народного горя": В Петербурге почтут память жертв политических репрессий] (in Russian). Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 "Perpetuating the Memory of the Victims of Political Repression: A List of Monuments and Commemorative Plaques in St. Petersburg" [Увековечение памяти жертв политических репрессий в Санкт-Петербурге: перечень памятников и мемориальных досок] (PDF) (in Russian). Human Rights Ombudsman for Saint Petersburg. 2018. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2018-12-22. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 Khazanov, A. M. (2017). ""Whom should we Mourn, Whom Forget? The (re)construction of Collective Memory in Modern Russia"" [О ком скорбеть и кого забыть? (Ре)конструкция коллективной памяти в современной России] (in Russian). Historical Expertise Magazine. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ Etkind, A. (2004-08-03). ""No Traces of the Gulag remain in Russia"" [В России не осталось следов Гулага] (in Russian). Süddeutsche Zeitung. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 Zolotonosov 2005, p. 196.

- 1 2 3 4 Budkevich, M. (2002). ""A New Monument in St. Petersburg"" [Новый памятник в Санкт-Петербурге] (in Russian). Gazeta Petersburska, № 6—7 (42). ISSN 2219-9470.

- ↑ Voltskaya, T. (2018-10-05). ""The Great Terror: the Leningrad's Night of Shot Poets"" [Большой террор: ночь расстрелянных поэтов Ленинграда]. Peterburg of Freedom. The Archives (in Russian). Radio Svoboda.

- 1 2 Etkind, A. (2004). ""A time to compare stones. The post-Revolutionary Culture of Political Mourning in Modern Russia"" [Время сравнивать камни. Постреволюционная культура политической скорби в современной России]. Ab Imperio (in Russian). Ab Imperio magazine. ISSN 2166-4072. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ "Burials next to the Petropavlovsk fortress", Russia's Necropolis.

- ↑ ""Memorials to Victims of Political Repression in Russia. A Brief Profile"" [Памятники жертвам политических репрессий в РФ. Досье] (in Russian). TASS Russian News Agency. 15 January 2015. Archived from the original on 2018-12-04. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Zolotonosov, M. (2002). ""I would like to recall them all by name"" [Хотелось бы их поименно назвать] (in Russian). The Moscow News. Archived from the original on 2016-04-03. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ Putilova, E. (11 May 2013). ""Perpetuating the Memory of the victims of Political Repression—is that all Memorial should do?"" [Увековечение памяти жертв политических репрессий—дело "Мемориала". И только?] (in Russian). Cogita!ru. Archived from the original on 2018-10-11. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ ""Yuly Rubakov and the Solovki Stone in St. Petersburg"" [Юлий Рыбаков и Соловецкий камень в Питере] (in Russian). Solovki Encyclopaedia. 4 September 2002. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- ↑ ""Memorial turns 24" (+ Photo)" [24 года назад было учреждено общество "Мемориал" (+ ФОТО)] (in Russian). Human Rights Society website (Ryazan). 28 January 2013. Retrieved 2020-03-16.

- 1 2 3 4 Ansberg & Margolis 2009.

- ↑ Bulletin of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Congress of People's Deputies, Resolution No. 333 of 27 March 1990: "An open competition for the best concept, location and design proposal for a monument in honour of the victims of Stalin's terror" [Бюллетень исполнительного комитета Ленинградского городского совета народных депутатов. Решение исполкома Ленгорсовета № 333 от 27 марта 1990 г. "О проведении открытого конкурса на лучшую идею, место установки и проектное предложение памятника жертвам сталинских репрессий"]. Leningrad: Lenizdat. 1990. pp. 2–3.

- 1 2 Bulletin of the Executive Committee of the Leningrad City Congress of People's Deputies, Resolution No. 851 of 1 October 1990: "An open competition on the best concept, location and design proposal for a monument in honour of the victims of Stalin's terror" [Бюллетень исполнительного комитета Ленинградского городского совета народных депутатов. Решение исполкома Ленгорсовета № 851 от 1 октября 1990 г. "О проведении открытого конкурса на лучшую идею, место установки и проектное предложение памятника жертвам сталинских репрессий"]. Leningrad: Lenizdat. 1990.

- 1 2 Joffe 1998.

- ↑ Zolotonosov 2005, p. 197.

- ↑ Luba 1991.

- ↑ Zolotonosov 2005, pp. 197–198.

- 1 2 3 4 ""A mass grave of the victims killed in the Peter and Paul Fortress. 1917–1919"" [Захоронения расстрелянных в Петропавловской крепости. 1917–1919] (in Russian). Virtual Museum of the Gulag. 2 May 2014. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Lukina 1991.

- 1 2 Iofe 1998.

- ↑ Krivulin 1998.

- ↑ Volfson 2002, p. 6.

- ↑ Zolotonosov 2005, p. 198.

- ↑ Memorial societyo (ed.). "Zaretsky, Edward Vulfovich". Virtual Museum of the Gulag. Аlt-Soft.

- ↑ "The Tsayar Artistic Association" [Цаяр] (in Russian). The Saint Petersburg Encyclopaedia. Retrieved 2020-07-03.

- 1 2 3 4 Machinsky 2003.

- ↑ Zolotonosov 2005, p. 195.

- ↑ ""A monument to the victims of political repression in Saint Petersburg"" [Памятник жертвам политических репрессий в Петербурге] (in Russian). SPb Web Journal. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- ↑ Rezunkov, V. Dolinin (4 September 2002). "Vyacheslav Dolinin Вячеслав Долинин" (in Russian). Radio Svoboda. Retrieved 2020-07-20.

- ↑ "Names of the Victims of Political Repressiona are read aloud in St. Petersburg on the Day of Remembrance" [Имена убитых прочли у Соловецкого камня в Петербурге в День памяти жертв политических репрессий]. Fontanka.ru. 30 October 2018. Retrieved 2020-02-25.

- ↑ Kara-Murza Sr., Vladimir (13 February 2015). "The War against Monuments goes on" [Война с памятниками продолжается]. Радио Свобода (in Russian). Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Vishnevsky, Boris (2015-12-31). "Politkovskaya memorial event will go ahead despite ban" [n Будущее не за ними. Акция памяти Анны Политковской в Санкт-Петербурге состоится, несмотря на сопротивление властей] (in Russian). Novaya Gazeta. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Picket in St. Petersburg in Memory of Natalya Estemirova" [Пикет памяти Натальи Эстемировой в Петербурге] (in Russian). Cogita!ru. 19 July 2009. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Protest in memory of Natalya Estemirova held in St. Petersburg" [В Петербурге прошла акция памяти Эстемировой] (in Russian). Interfax. 16 July 2009. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Protest in memory of Stanislav Markelov and Anastasia Baburova took place in St. Petersburg" [Акции памяти Станислава Маркелова и Анастасии Бабуровой] (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 20 January 2011. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Nine days since the death of Alexei Devotchenko" [s Алексей Девотченко, 9 дней] (in Russian). Radio Liberty. 15 October 2014. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Plotnikova, A. (12 July 2013). "Event in memory of Natalya Gorbanevskaya in St. Petersburg" [Акция памяти Горбаневской в Петербурге] (in Russian). Voice of America. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "The late Valeria Novodvorskaya is remembered in St. Petersburg" [В Петербурге почтили память Валерии Новодворской] (in Russian). Radio Liberty. 16 July 2014. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Spontaneous gathering in memory of Boris Nemtsov held in St. Petersburg" [Стихийный митинг памяти Бориса Немцова в Петербурге] (in Russian). Cogita!ru. 28 February 2015. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Voltskaya, T. (19 October 2019). "Civic funeral in St. Petersburg to honour the late Vladimir Bukovsky" [В Петербурге состоялась гражданская панихида по Владимиру Буковскому] (in Russian). Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Voltskaya, T. (4 June 2016). "Event in memory of those who died in the prisons of Petrograd and Leningrad" [Прошли акции памяти погибших в тюрьмах Петрограда-Ленинграда]. Радио Свобода (in Russian). Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ↑ Kosinova, T. (14 August 2012). "75 years since the Great Terror began" [75 лет после Большого террора] (in Russian). Cogita!ru. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ↑ Bondarev, V. (21 December 2016). "Secret police officer's day marked at the Solovki Stone" [У Соловецкого камня в Санкт-Петербурге отметили День чекиста]. RFI.fr. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ↑ Vishnevsky, B. (14 February 2018). "Smolny permits Yabloko protest to go ahead" [Смольный одобрил протестную акцию "Яблока"] (in Russian). Zaks.ru. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ↑ Bondarev, Vladimir (18 February 2018). "'No more deaths!' Protest in St. Petersburg against the torture of activists" ["Хватит убивать!": в Петербурге прошел митинг против пыток активистов] (in Russian). RFI. Retrieved 2020-03-20.

- ↑ Tur, Tamara (30 October 2002). "Already desecrated" [Уже осквернили] (in Russian). Memorial newspaper. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Vandals desecrate the Solovki Stones" [Вандалы оскверняют Соловецкие камни] (in Russian). Solovki Encyclopaedia. 26 April 2003. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Solovki Stone desecrated in St. Petersburg" [В Петербурге осквернили Соловецкий камень] (in Russian). Lenta.ru. 9 February 2012. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Vandals scribble all over Petersburg's Solovki Stone" [Вандалы разрисовали Соловецкий камень в Петербурге] (in Russian). RIA Novosti. 28 February 2013. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Desecrated monument cannot be restored before departmental responsibility is established" [Расписанный вандалами памятник в Санкт-Петербурге не могут отреставрировать до определения его ведомственной принадлежности] (in Russian). TASS. 3 December 2013. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Some entertainment for the Ombudsman: Alexander Shishliov cleans monument to Andrei Sakharov" [Аттракцион для Уполномоченного: Александр Шишлов очистил памятник главному российскому правозащитнику Андрею Сахарову] (in Russian). Ombudsmanspb.ru. 25 April 2015. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Gavrilina, S. (22 December 2015). "Hitler proclaimed a "victim" of political repression" [Гитлера объявили "жертвой политических репрессий"] (in Russian). Nezavisimaya Gazeta. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ Voltskaya, T. (6 December 2018). "Those killed are denounced: Who wants to take down the plaques installed by the 'Last Address' organisation?" [Донос на расстрелянных. Кто хочет снять таблички "Последнего адреса"]. Радио Свобода (in Russian). Radio Liberty. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

- ↑ "Head of Petersburg city administration pays his respects to the Victims of Political Repression" [Глава города почтил память жертв политических репрессий] (in Russian). St. Petersburg City Administration. 30 October 2018. Retrieved 2020-03-19.

Comments

- ↑ Some researchers criticize this choice because the incident at the infirmary, the Savvatiyev Skethe, was only a small episode in the history of the Solovki camp and the Gulag. It was a prison for former revolutionaries of 1917, moreover, who enjoyed privileges because of their special status as political prisoners: they had much better conditions than other convicts. Other researchers consider their protest was not a rebellion intended to protect the human rights of all prisoners, but merely a fight for their own privileged status.[10]

- ↑ Some have criticized this idea for its mystical and religious undertones. The Russian Orthodox Church used the same concept, however, in designing the cross at the Butovsky which is also based on the Solovki Stone and was made on the Solovetsky Islands.[16]

- ↑ As rumored in the Soviet times, the Bolshoy Dom was a place where political prisoners were tortured and murdered. However, in fact the victims were moved out and killed on other locations.[27]

- ↑ Such proximity to sites of State Terror, some say, emphasize the significancwe and continuing relevance of the Solovki Stone. Others suggest that the monument's location next to a site where earlier killings took place demonstrates that the old political regime was not fully replaced by the new.[15]

Information under Location of the Solovetsky Stone has erroneously listed buildings in St Petersburg instead of Moscow.

Sources

Latin alphabetical order

- Ansberg, O. N.; Margolis, A. D. (2009). Life in Leningrad during Perestroika, 1985–1991 [Общественная жизнь Ленинграда в годы перестройки. 1985–1991] (PDF). St. Petersburg: Silver House publishers. p. 784. ISBN 978-5-902238-60-7.

- Applebaum, Anne (2012). Gulag: A History of the Soviet Camps. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780141975269.

- Barnes, Steven A. (2011). Death and Redemption: The Gulag and the Shaping of Soviet Society. Princeton: Princeton University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-691-15112-0.

- Dolinina, Kira (6 May 1995). "Monument unveiled in St. Petersburg: Michail Chemiakin is annoyed by disappointed ditizens" [Открытие памятника в Санкт-Петербурге. Михаил Шемякин остался недоволен недовольными им петербуржцами]. Kommersant (in Russian). St. Petersburg edition. ISSN 1561-347X.

- Jakobson, Michael (1993). The Origins Of The Gulag: The Soviet Prison Camp System, 1917–1934. The University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-5622-4.

- Joffe, Veniamin (1998). On optimism: New essays and speeches [Новые этюды об оптимизме: Сборник статей и выступлений] (PDF). St. Petersburg: Memorial. pp. 27–28, 38–39, 123, 128–129. ISBN 978-5-902238-60-7.

- Krivulin, V. (1998). The Tsar and the Sphinx: Hunting a Mammoth [Царь и сфинкс // Охота на мамонта]. St. Petersburg: Blitz Russian-Baltic Info Agency. p. 334. ISBN 5-86789-073-2.

- Lukina, L. (1991). "Will the competition continue?" [Конкурс будет продолжен?]. Vecherny Leningrad (in Russian). Leningrad.

- Luba, Y. B. (1991). "In Memory of the Victims" [В память о жертвах]. Vecherny Leningrad magazine (in Russian). Leningrad.

- Machinsky, D. A. (2003). "Light from the Dark—A year without Veniamin Joffe, about the Stone" [Свет из тьмы: Год без Вениамина Иофе. О явлении камня]. "Terra Incognita" human rights almanac (in Russian). No. № 4—5 (14–15). St. Petersburg.

- Melgunov, S. P. (2015). Red Terror in Russia, 1918-1923 [Красный террор в России 1918–1923] (in Russian). Moscow-Berlin: DirectMedia. p. 270. ISBN 978-5-4475-5965-6.

- Memorial Research & Information Centre (St. Petersburg) [НИЦ «Мемориал»] (ed.). "The Solovki Stone on Trinity Square in St. Petersburg [Соловецкий Камень на Троицкой площади в Санкт-Петербурге]". The Virtual Museum of the Gulag, archives [Виртуальный музей Гулага. Фонды]. Alt-Soft Ltd. Archived from the original on 2019-04-04. Retrieved 2019-11-04.

- Sakharov Center (Moscow), ed. (2019). "A Monument to the Victims of Political Repression in Petrograd-Leningrad [Памятник жертвам политических репрессий Петрограда—Ленинграда]". Memorials and commemorative plaques to the victims of political repression in the former Soviet Union [Памятники и памятные знаки жертвам политических репрессий на территории бывшего СССР]. Archived from the original on 2019-01-12.

- Volfson, M. (2002). "The Stone of History" [Камень истории]. Pravoe Delo magazine (in Russian). Vol. 35, no. 53. p. 6.

- Zolotonosov, M. N. (2005). A monument for victims of Political Repression in Petrograd-Leningrad [Памятник жертвам политических репрессий в Петрограде-Ленинграде]. St. Petersburg: Noviy Mir Iskusstva. pp. 195–199. ISBN 5-902640-01-6.

External links

- Russia's Necropolis of Terror and the Gulag. A select directory of burial grounds and commemoratives sites in Russia.