| Soltan Hoseyn شاه سلطان حسین | |

|---|---|

Portrait of Soltan Hoseyn in the Reizen over Moskovie, door Persie en Indie by Cornelis de Bruijn, dated 1703.[1] It is currently located in the Bibliothèque nationale de France in Paris.[2] | |

| Shah of Iran | |

| Reign | 6 August 1694 – 21 October 1722 |

| Coronation | 7 August 1694 |

| Predecessor | Suleiman of Persia |

| Successor | Tahmasp II (Qazvin) Mahmud Hotaki (Isfahan) |

| Born | 1668 |

| Died | 9 September 1727 (aged 59) Isfahan |

| Burial | |

| Spouse |

|

| Issue | See below |

| Dynasty | Safavid dynasty |

| Father | Suleiman of Persia |

| Mother | Unnamed Circassian woman |

Soltan Hoseyn[lower-alpha 1] (Persian: شاه سلطان حسین, romanized: Soltān-Hoseyn; 1668 – 9 September 1727) was the Safavid shah of Iran from 1694 to 1722. He was the son and successor of Shah Suleiman (r. 1666–1694).

Born and raised in the royal harem, Soltan Hoseyn ascended the throne with limited life experience and more or less no expertise in the affairs of the country. He was installed on the throne through the efforts of powerful great-aunt, Maryam Begum, as well as the court eunuchs, who wanted to increase their authority by taking advantage of a weak and impressionable ruler. Throughout his reign, Soltan Hoseyn became known for his extreme devotion, which had blended in with his superstition, impressionable personality, excessive pursuit of pleasure, debauchery, and wastefulness, all of which have been considered by both contemporary and later writers as elements that played a part in the decline of the country.

The last decade of Soltan Hoseyn's reign was marked by urban dissension, tribal uprisings, and encroachment by the country's neighbours. The biggest threat came from the east, where the Afghans had rebelled under the leadership of the warlord Mirwais Hotak. The latter's son and successor, Mahmud Hotak made an incursion into the country's centre, eventually reaching the capital Isfahan in 1722, which was put under siege. A famine soon emerged in the city, which forced Soltan Hoseyn to surrender on 21 October 1722. He relinquished his regalia to Mahmud Hotak, who subsequently had him imprisoned, and became the new ruler of the city. In November, Soltan Hoseyn's third son and heir apparent, declared himself as Tahmasp II in the city of Qazvin.

Soltan Hoseyn was beheaded on 9 September 1727 under the orders of Mahmud Hotak's successor Ashraf Hotak (r. 1725–1729), due to an insulting letter sent by the Ottoman commander-in-chief Ahmad Pasha, who claimed that he had marched into Iran in order to restore Soltan Hoseyn to the throne.

Background

Soltan Hoseyn was born in 1668 in the royal harem.[3] He was the eldest son of Shah Solayman (r. 1666–1694) and a Circassian woman. He had the same upbringing as his father, being raised in the royal harem, and thus having limited life experience and more or less no expertise in the affairs of the country.[4] At best, Soltan Hoseyn is known to have read the Quran under the guidance of Mir Mohammad-Baqer Khatunabadi. Although Soltan Hoseyn seems to have been able to speak Persian, he preferred to speak in Azeri Turkish, similar to the majority of Safavid shahs.[3]

When Shah Solayman was on deathbed, he reportedly told his courters, that if they wanted fame for the royal family and the country, then they should choose the younger son Sultan Tahmasp (aged 23). However, if they sought peace and calmness, they should choose the elder son, Soltan Hoseyn (aged 26). The French missionary priest Père Martin Gaudereau, who was in the capital of Isfahan during this period, reports that Shah Solayman was more inclined towards Sultan Tahmasp as his successor. Nevertheless, Soltan Hoseyn's succession to the throne was secured by his powerful great-aunt, Maryam Begum, as well as the court eunuchs, who wanted to increase their authority by taking advantage of a weak and impressionable ruler.[3]

Enthronement

Due to disagreements between the palace ranks and the desire to have the enthronement take place at a well-timed moment, Soltan Hoseyn was first enthroned on 7 August 1694, a week after his father's death (29 July).[3] Several preparations were made before the enthronement. To assure stability amongst the populace, the whole city was stationed with troops. In order to make the shah's soul gain tranquility, an abundance of food was made accessible, including to the poor.[3] The merchants in the bazaar were instructed to place lights in front of their stores. On the day of the inauguration, at 4 o'clock, trumpets were blown after having been unused for fifteen days. During that night, the Royal Square (Maydan-e Shah) and the surrounding bazaars were lit with bright lights, and all types of animals were shown off in the square. However, Soltan Hoseyn was himself enthroned in the Ayena-khana palace on the southern bank of the Zayanderud, thus foreshadowing his provincialism and detachment.[3]

Unlike his predecessors, Soltan Hoseyn rejected the custom of having the leader of the Sufis to equip him with a sword during the ceremony. Instead, he asked the shaykh al-Islam of Isfahan and leading cleric, Mohammad-Baqer Majlesi, to carry out this responsibility. Maljesi assembled a different type of gathering, where he granted Soltan Hoseyn the title of dinparvar (nurturer of the faith). When Soltan Hoseyn asked Majlesi what he wanted in return, he asked for the implementation of Sharia law. Subsequently, 6,000 bottles of wine from the royal cellars were said to have been poured out on the square in a pompous manner.[3] A decree was declared which prohibited all types of "unislamic" actions, such as the manufacture and drinking of alcohol, youngsters visiting coffeehouses, and women going out without male company. Leisure activities such as pigeon-flying and playing games were also banned. This was made public in the provinces and engraved in stone friezes above mosques.[3]

The fluid transition of power to Soltan Hoseyn demonstrates that the realm's numerous leading factions were still working more together than clashing.[5]

However, authority soon shifted away from Muhammad Baqer Majlesi to Soltan Hoseyn's great aunt, Maryam Begum (the daughter of Shah Safi). Under her influence, Hosein became an alcoholic and paid less and less attention to political affairs, devoting his time to his harem and his pleasure gardens.[6]

Major events and developments

The North

Azerbaijan

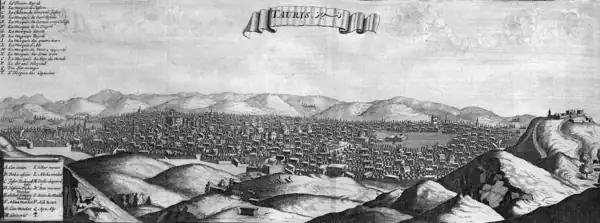

Azerbaijan, possibly the leading province concerning income and army recruitment, was in a state of chaos by 1711. During the early part of that year, a vague and violent conflict took place in Tabriz, allegedly resulting in the death of 3,000.[7] In the ensuing years, the inhabitants of the city greatly suffered due to high prices and oppressive management. During the early part of 1719, they revolted against the city's cruel governor, Mohammad-Ali Khan, who fled as a result. The government in Isfahan subsequently punished the inhabitants of Tabriz with a heavy fine. In 1721, Tabriz was affected by a deadly earthquake, causing the destruction of 75% of the city and the death of over 40,000 inhabitants.[7]

Shirvan

In 1702, Shirvan was described by the Dutch traveler Cornelis de Bruijn as one of the key provinces of the Safavid realm, admiring it for its fertility, high agricultural yield and cheap prices. The province was then controlled by Allahverdi Khan, known for his assertive and fair rule. However, when de Bruijin returned to Shirvan in 1707, the province was in disarray due to the mismanagement of Allahverdi Khan's son and successor, who was more interested in women and wine. de Bruijin spoke with locals who stated that they would rather live under Russian rule and would not oppose an invasion by them. In 1709, Lezghi mountaineers capitalized on the power vacuum in Shirvan by launching raids into the province.[7]

Russo-Persian War

In June 1722, Peter the Great, the then tsar of the neighbouring Russian Empire, declared war on Safavid Iran in an attempt to expand Russian influence in the Caspian and Caucasus regions and to prevent its rival, Ottoman Empire, from territorial gains in the region at the expense of declining Safavid Iran.

The Russian victory ratified for Iran's cession of their territories in the Northern, Southern Caucasus and contemporary mainland Northern Iran, comprising the cities of Derbent (southern Dagestan) and Baku and their nearby surrounding lands, as well as the provinces of Gilan, Shirvan, Mazandaran, and Astrabad to Russia per the Treaty of Saint Petersburg (1723).[8]

The East

Balochi raids

The most exposed part of Iran's frontier was located in the extensive arid lands to the east. The area was populated by tribes that neither the Safavids nor the Mughals were ever successful in pacifying.[9] In 1699, the Kerman province was overwhelmed by a Balochi invasion.[3]

In response, Soltan Hoseyn appointed the Georgian prince Gorgin Khan (George XI) as beglerbeg (governor) of Kerman. The latter had previously served as the vali (viceroy) of Georgia, but had been dismissed in 1688 for helping rebel forces against the Safavid governor of Kakheti.[10] Brave and strong-willed during warfare, Gorgin Khan preferred to use as the solution to any problem.[11] With the help of his brother Shahqoli Khan (Levan), he routed the numerically superior Balochis in various encounters. In 1703, as a result of incursions by the Afghans, Soltan Hoseyn appointed Gorgin Khan as the sepahsalar (commander-in-chief) and governor of Qandahar, as well as the vali of Georgia.[10]

Gorgin Khan's governorship of Qandahar

At Qandahar, Gorgin Khan soon competed against Mirwais Hotak, a chief of the Hotaki clan of the Afghan Ghilzai tribe, who also served as the kalantar (mayor) of the city.[12] An affluent man from prominent family, Mirwais was charitable towards his supporters and the poor.[13] He had been under service of the Safavids for a long time, serving as the qafilah-salar, whose function was to patrol the caravan passage between Iran and India.[14] However, he was dismissed as qafilah-salar in 1706, apparently due to his poor service and negligence of his responsibility in collecting fees and taxes.[3][15] Meanwhile, the Afghan relations with Gorgin Khan had become uneasy due to his oppressive rule.[15] Most sources agree that his rule started to become oppressive quickly after his assumption of power in Qandahar.[10]

The (nominally Shi'i) Georgian soldiers of Gorgin Khan concealed goods, seized Afghan girls and women, and increased taxes. They also disregarded the religious freedom that the Sunni Afghans had been guaranteed as a condition for accepting Safavid rule. They were said to have defiled Sunni mosques by bringing pigs and wine inside, as well as taking advantage of underaged girls and 9-10 year old boys, with some of them ending up being killed, and their corpses thrown in front of their parents' homes.[15]

The Afghans, aggrieved by this treatment, sent complaints to Isfahan, but they were seized by Gorgin Khan's men at the court and thus never reached Soltan Hoseyn.[15] Mirwais planned to rebel against the Georgians, but was soon arrested and brought to Isfahan under the orders of Gorgin Khan, who was suspicious of him.[16] The latter urged Soltan Hoseyn to eliminate him, or at least prohibit him from going back to Qandahar.[17] During his stay at Isfahan, Mirwais observed the fragility of the Iranian regime, as well as the possibility to benefit from the factional strife there.[18] Through proficient flattery and bribery, he successfully reintegrated himself. He persuaded Soltan Hoseyn that Gorgin Khan was not trustworthy, as he planned to make his rule in Qandahar autonomous, and also planned a Russo-Georgian alliance against Iran.[17]

The rebellion of Mirwais

Mirwais was given permission to go on a pilgrimage to Mecca, where he convinced the religious authorities to declare a fatwa that gave the Afghans the right to become independent of Iranian control. In 1708, he was sent back to Qandahar as a shadow administrator, where he launched a massive rebellion. In April 1709, the Afghans made a surprise attack against Gorgin Khan and his retinue, killing them in their tents. They subsequently took control over Qandahar, and massacred its Georgian garrison. The news of these developments did not motivate the government to take action. Soltan Hoseyn instead sent two emissaries in a row to protest, but they were both jailed.[13]

Soltan Hoseyn then responded by selecting Gorgen Khan's nephew Khosrow Khan (Kay Khosrow) as the commander of the Afghan expedition.[17] The latter had previously served as the darugha (prefect) of Isfahan,[19] and following Gorgin Khan's death became the new sepahsalar and vali of Georgia.[12] Khosrow Khan struggled to prepare the expedition, as he was given an insufficient amount of 7,000 to pay for 3,000 soldiers. The grand vizier, as well as members of the anti-Georgian court faction, greatly hindered the release of funds for the expedition. Khosrow Khan instead found reassurance through military support by the Herat-based Afghan Abdali tribe, the adversaries of the Ghilzai.[17]

After two years of warfare with the Ghilzai, Khosrow Khan finally besieged Qandahar with Abdali assistance. Two months, later the Ghilzai appealed for peace. However, after being demanded of total surrender to the Iranian forces, they continued fighting. In October 1711, Khosrow Khan and his exhausted soldiers were forced to withdraw, due to the summer heat, illness, shortage of supplies, and attacks by the Baluchi, who had joined the Afghans. Khosrow Khan and many of his troops were killed by the pursuing Afghan soldiers, who took their military equipment.[17]

In late 1712, the qorchibashi (head of the mounted cavalry or royal guards[20]) Mohammad Zaman Khan was entrusted with the task of attacking the Afghans whilst assembling an army en route. However, the lack of funds greatly hindered his expedition. Rather than using money from his own treasury, Soltan Hoseyn forced the merchants in Isfahan and New Jolfa to give a combined amount of 14,000 tomans. The expedition eventually fell apart when Zaman Khan died near Herat in the spring of 1712.[21]

He was succeeded by Mansur Khan Shahsevan, whose expedition also ended in failure. He left Isfahan in September 1713 with fifty troops and more or less without any funds. Meanwhile, Sultan Husayn had forced his courtiers to lend him money to construct a new maydan (town square) in Farahabad. During the summer of 1713, 500 soldiers were marching towards the east, with no funds and horses and equipped with sticks. Mahd Ali Khan, who governed Farah, was unable to march towards with his 1,500 soldiers towards Mirwais due to lack of funds. Many of his soldiers had deserted and made the countryside dangerous, causing the locals more trouble than the Afghans. Meanwhile, the local militia of Marv had revolted due to the lack of pay, and a force of 8,000 Turkmens were marching towards Mashhad.[21]

The Afghan capture of Isfahan

Following the death of Mirwais in 1715, the Iranians failed in their efforts to appease the Afghans through compromises, as Mirwais's son and later successor Mahmud Hotak (r. 1717–1725) swore to get his revenge against the Iranians. The Afghans advanced into the heartland of Iran in 1720, conquering Kerman. Six months later, they chose to withdraw, but came back the next year, causing chaos in the southeast and eastern part of the country. Nevertheless, Soltan Hosayn continued to use the majority of his time and funds on construction projects.[3] Mahmud and his army swept westward aiming at the shah's capital of Isfahan itself. Rather than biding his time within the city and resisting a siege in which the small Afghan army was unlikely to succeed, Soltan Hoseyn marched out to meet Mahmud's force at Golnabad.[22] Here, on 8 March, the royal army was thoroughly routed and fled back to Isfahan in disarray.[23]

The shah was urged to escape to the provinces to raise more troops but he decided to remain in the capital which was now encircled by the Afghans.[24] Mahmud's siege of Isfahan lasted from March to October, 1722. Lacking artillery, he was forced to resort to a long blockade in the hope of starving the Iranians into submission.[25] Soltan Hoseyn's command during the siege displayed his customary lack of decisiveness and the loyalty of his provincial governors wavered in the face of such incompetence.[26] Protests against his rule also broke out within Isfahan and the shah's son, Tahmasp, was eventually elevated to the role of co-ruler. In June, Tahmasp managed to escape from the city in a bid to raise a relief force in the provinces, but little came of this plan.[27] Starvation and disease finally forced Isfahan into submission. It is believed that over 80,000 of the inhabitants of the city died during the siege. On 23 October, Soltan Hoseyn abdicated and acknowledged Mahmud as the new shah of Iran.[28]

Captivity and death

Mahmud initially treated Soltan Hoseyn considerately, but as he gradually became mentally unbalanced he began to view the former shah with suspicion.[29] In February 1725, believing a rumour that one of Soltan Hoseyn's sons, Safi Mirza, had escaped, Mahmud ordered the execution of all the other Safavid princes who were in his hands, with the exception of Soltan Hoseyn himself. When Soltan Hoseyn tried to stop the massacre, he was wounded, but his action saved the lives of two of his young children. Mahmud succumbed to insanity and died on 25 April of the same year.[30]

Mahmud's successor Ashraf Khan at first treated the deposed shah with sympathy. In return, Soltan Hoseyn gave him the hand of one of his daughters in marriage, a move which would have increased Ashraf's legitimacy in the eyes of his Iranian subjects. However, Ashraf was involved in a war with the Ottoman Empire, which contested his claim to the Iranian throne. In the autumn of 1726, the Ottoman governor of Baghdad, Ahmad Pasha, advanced with his army on Isfahan, sending an insulting message to Ashraf saying that he was coming to restore the legitimate shah to the throne. In response, Ashraf had Soltan Hoseyn's head cut off and sent it to the Ottoman with the message that "he expected to give Ahmad Pasha a fuller reply with the points of his sword and his lance". As the Iranologist Michael Axworthy comments, "In this way Shah Soltan Hoseyn gave in death a sharper answer than he ever gave in life".[31]

Religious policy

%252C_Safavid_Iran%252C_dated_March-April_1713-14.jpg.webp)

Soltan Hoseyn's religiosity is implied through the numerous awqaf (charitable endowment under Islamic law) he gifted. He may not have been as intolerant as he commonly is described, as implied by his trust in the Sunni grand vizier Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani, his interest when visiting to the churches of New Jolfa, as well as the numerous decrees (farman) he declared, which protected the Christian population of Iran and allowed missionaries to perform their operations. That status of European missionaries was better under Soltan Hoseyn than that of his father.[3]

The clerics, who held influence over Soltan Hoseyn, were permitted to pursue their dogmatic plans, such as their anti-Sufi policies and taking action against non-Shi'ites. These actions included the forced conversion of Zoroastrians, and converting their temple in Isfahan into a mosque, exacting jizya (poll tax) from Jews and Christians, and making it illegal for non-Shi'ites to go outside during rain for fear that they may pollute Shi'ites. In most cases these laws were avoided through bribery, or in other occasions through other means, such as when Maryam Begum interceded on the behalf of the Armenians of New Jolfa.[3]

Nevertheless, the progressively intolerant environment caused by these measures decreased the loyalty of the non-Shi'ites towards the Safavid government. Due to increased taxes and endangerment by a law that permitted the family member of an apostate to gain their belongings, several wealthy Armenians withdrew much of their financial assets and left for the Italian cities of Venice and Rome. The anti-Sunni policies pursued by the government had the most substantial consequences, as it alienated the many Sunnis of the country, most of whom inhabited its frontiers.[3]

Soltan Hoseyn also had the tawhid-khana (Sufi assemblies) closed.[3]

Foreign Policy

While less involved with the outside world than his predecessors, Soltan Hoseyn was more engaged in foreign policy than that of his father. He continued the latter's policy of preserving peaceful relations with the Ottoman Empire.[3]

Government

During the reign of Soltan Hoseyn, the structure of the government remained unchanged, continuing the same multi-constitutional foundations (Turk, Tajik,[lower-alpha 2] gholam) that had existed earlier. Soltan Hoseyn's first grand vizier was the Tajik sayyid Mohammad Taher Vahid Qazvini,[33] who had held the office since 1691, during the reign of Shah Soleyman.[34] Mohammad Taher Vahid, as well to a lesser degree the court steward (nazer) Najafqoli Khan, were the main counselors of Soltan Hoseyn during his early reign.[3] In May 1699, Soltan Hoseyn dismissed Mohammad Taher Vahid, supposedly due to the latter's old age. He replaced him with the eshik-aqasi-bashi Mohammad Mo'men Khan Shamlu, who, however, was also advanced in age.[35]

He was in turn replaced in 1707 by Shahqoli Khan Zanganeh, son of the Sunni Kurd Shaykh Ali Khan Zanganeh, who had also previously served as grand vizier.[33] He was succeeded in 1715 by the Sunni Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani, whom Soltan Hoseyn left most of the state affairs to.[3][33] The French consul Ange Garde considered Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani to be the "absolute ruler of the realm, who takes care of everything while the king has not the slightest knowledge of what goes on in the country."[36] He was succeeded in 1720 by Mohammad Mo'men Khan Shamlu's son Mohammad Qoli Khan Shamlu, who remained grand vizier until the fall of Isfahan.[33][37]

The high clerics were notably favoured and regarded by Soltan Hoseyn, particularly Maljesi, whom he often consulted and entrusted to write texts about religious subjects. Following Majlesi's death in 1669, Soltan Hoseyn's former tutor Khatunabadi succeeded him in that regard.[3] The latter was given the most powerful religious office of the country, the mullabashi, an office first created by Soltan Hoseyn.[38] The courts eunuchs also uninterruptedly increased their influence, such as in 1696, when the head of the black eunuchs, Agha Kamal, was the most praised subject of Soltan Hoseyn. By 1714, it was the eunuchs who decided who was promoted, appointed or discharged. During Soltan Hoseyn's late reign, the most prominent influence was exercised by Maryam Begum.[3]

There were many who held the post of sepahsalar under Soltan Hoseyn, primarily members of the Shamlu and the Zanganeh tribes. The post of qorchibashi (head of the mounted cavalry or royal guards) continued to be held by tribal groups, also primarily the Shamlu and Zanganeh.[39] The post of qollar-aghasi (chief of the gholams[40]) was held by officers of tribal and Georgian gholam origin.[33] The post of sadr continued to be held by Tajik sayyids.[33] The provincial bureaucracy mainly imitated that of the central bureaucracy, and was thus controlled by members of leading local Tajik families, often of sayyid origin.[33]

Personality

Throughout his reign, Soltan Hoseyn became known for his extreme devotion, which had blended in with his superstition, impressionable personality, excessive pursuit of pleasure, debauchery, and wastefulness, all of which have been considered by both contemporary and later writers as elements that played a part in the decline of the country. Because of his piety, he received the nicknames "Darvish", "Molla" and "Molla Husayn," and became known as a monarch whose doings were only in line with the Sharia law. Soltan Hoseyn demonstrated his devotion by depriving alcohol and female dancers from royal ceremonies. However, a few months after his enthronement, he started drinking, reportedly under the influence of Maryam Begum, who also drank. Despite his religiosity, Soltan Hoseyn kept the openly Sunni Fath-Ali Khan Daghestani as his grand vizier for five years.[3]

The meek aspect of Soltan Hoseyn is reported by all eyewitnesses, who displayed it as either benevolence and rightfulness, or as an absence of determination, which played a part in the collapse of the Safavid kingdom. Judasz Tadeusz Krusinski considers Soltan Hoseyn to have been "less able and resolute than his father" and "good-natured and human" who "hurt no particular person and by that means hurt all mankind."[3] When asked to make a choice, Soltan Hoseyn usually supported the suggestion made by the last person he spoke to, often with the words yakhshi dir ("It is good" in Turkic). He was said to have used that phrase so much that the eunuchs and courtiers nicknamed him after it in secret.[41] The Iranologist Rudi Matthee considers Soltan Hoseyn's use of the phrase a demonstration of his naivety.[3]

Like Krusinski, Abd al-Hoseyn Khatunabadi also portrays Soltan Hoseyn as kind and against spilling blood. Contrary to the previous Safavid shahs, Soltan Hoseyn did not harm any of his opponents or family members, and was also unable to do the same to animals. While previous Safavid shahs had used death as a type of punishment, Soltan Hoseyn used relinquishment of wealth and financial fines as the highest punishment. According to John Malcolm, writing in 1815, Soltan Hoseyn did not possess the bloodshed and brutality of his father, but that his "bigotry proved more destructive to the country than the vices of Soleyman." Soltan Hoseyn's kind personality was considered by many of his subjects as a proof of his weakness.[3]

Building projects

In Isfahan, Soltan Hoseyn ordered the construction of Chaharbagh School, the largest building to be created since the reign of Shah Abbas I (r. 1588–1629). It was located to the east of Chaharbagh avenue.[42]

Coinage

Under Soltan Hoseyn, the minting of gold coins was reinstituted. When he lacked the funds to continue the taxing and fruitless military expeditions against the Afghans, he started to have gold ashrafi currency minted in 1717. The number of coin mints during the reign of Soltan Hoseyn heavily decreased. The weight of the abbasi currency was reduced a few times, from 7.39g (between 1694 and 1711) to 6.91g (between 1711 and 1717), and then to 5.34g (1717–1722). Its weight reached its lowest during the Afghan siege of Isfahan, weighing 4.61g.[43]

Issue

Soltan Hoseyn married numerous times;

- (1); 1694, a daughter of Vahshatu Sultan, Safi Quli Khan.

- (2); a daughter of Vakhtang V (Shah Nawaz Khan II), King of Kartli.

- (3); 1710 Farda Begum Sultan, also known as Princess Khoreshan (died 1732, m. second, ca. 1727, the Khan of Erevan), daughter of Kaikoshrow, King of Kartli and commander-in-chief of the Persian army.

- (4); Amina Begum, alias Khair un-nisa Khanum (m. second, ca. 1713, Amir Fath 'Ali Bahador Khan-e Qajar Quyunlu, Nai'b us-Sultana), daughter of Husain Quli Agha.

Sons

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Mahmud Mirza (b.1697-k. 8 February 1725), Vali Ahad

- Safi III (b.1700 – d. 1726)

- Tahmasp II

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Mehr Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Heydar Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Salim Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Soleyman Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Ismail Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Mohammad Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Sultan Khalil Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Mohammad Baqer Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

- Prince Shahzadeh Mohammad Ja'afar Mirza (k. 8 February 1725)

Daughters

- Razia Begum (died 1776, Karbala), married Nader Shah in 1730;[44]

- Fatima Sultan Begum (died 5 February 1740, Mashhad), married Prince Reza Qoli Mirza eldest son of Nader Shah;[45]

- Maryam Begum or Khan Aqa Begum, married Sayyid Murtaza;[45]

See also

Notes

References

- 1 2 3 Matthee 2011, p. 166.

- ↑ Mokhberi 2019, p. 92.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 15 16 17 18 19 20 21 22 23 24 Matthee 2015a.

- ↑ Matthee 1997, p. 854.

- ↑ Newman 2008, p. 104.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 30–31.

- 1 2 3 Matthee 2011, p. 222.

- ↑ Kazemzadeh 1991, p. 319.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 231.

- 1 2 3 Matthee 2002, pp. 163–165.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, p. 35.

- 1 2 Matthee & Mashita 2010, pp. 478–484.

- 1 2 Axworthy 2006, p. 36.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, pp. 148, 233.

- 1 2 3 4 Matthee 2011, p. 233.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, pp. 233–244.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Matthee 2011, p. 234.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, p. 37.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 234. For the function of prefect, see p. 257.

- ↑ Newman 2008, p. 17.

- 1 2 Matthee 2011, p. 235.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, p. 44.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 47–49.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 50–51.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, p. 51.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 52.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 52–53.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 54–55.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 64–65.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, pp. 86–88.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 27.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Newman 2008, p. 105.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 72.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 204.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 209.

- ↑ Matthee 2011, p. 214.

- ↑ Anzali & Gerami 2018, p. 9.

- ↑ Newman 2008, p. 105. For the function of the qorchibashi, see p. 17.

- ↑ Haneda 1986, pp. 503–506.

- ↑ Axworthy 2006, p. 33.

- ↑ Babaie 2021, p. 114.

- ↑ Akopyan 2021, p. 305.

- ↑ Perry, J.R. (2015). Karim Khan Zand: A History of Iran, 1747-1779. Publications of the Center for Middle Eastern Studies. University of Chicago Press. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-226-66102-5.

- 1 2 Kissling, H. J.; Spuler, Bertold; Barbour, N.; Trimingham, J. S.; Braun, H.; Hartel, H. (1 August 1997). The Last Great Muslim Empires. BRILL. p. 210. ISBN 978-9-004-02104-4.

Sources

- Akopyan, Alexander V. (2021). "Coinage and the monetary system". In Matthee, Rudi (ed.). The Safavid World. Routledge. pp. 285–309.

- Amanat, Abbas (2017). Iran: A Modern History. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0300112542.

- Anzali, Ata; Gerami, S. M. Hadi (2018). Opposition to Philosophy in Safavid Iran: Mulla Muḥammad-Ṭāhir Qummi's Ḥikmat al-ʿĀrifīn. Brill. ISBN 978-9004345645.

- Axworthy, Michael (2006). The Sword of Persia: Nader Shah, from Tribal Warrior to Conquering Tyrant. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-1850437062.

- Babaie, Sussan (2021). "Safavid Town Planning". In Melville, Charles (ed.). Safavid Persia in the Age of Empires: The Idea of Iran. Vol. 10. I.B. Tauris. pp. 105–132.

- Bournoutian, George (2021). From the Kur to the Aras: A Military History of Russia's Move into the South Caucasus and the First Russo-Iranian War, 1801–1813. Brill. ISBN 978-9004445154.

- Haneda, M. (1986). "Army iii. Safavid Period". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume II/5: Armenia and Iran IV–Art in Iran I. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 503–506. ISBN 978-0-71009-105-5.

- Kazemzadeh, Firuz (1991). "Iranian relations with Russia and the Soviet Union, to 1921". In Avery, Peter; Hambly, Gavin; Melville, Charles (eds.). The Cambridge History of Iran. Vol. 7. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-20095-0.

- Matthee, Rudi (1997). "Sulṭān Ḥusayn". In Bosworth, C. E.; van Donzel, E.; Heinrichs, W. P. & Lecomte, G. (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam. Volume IX: San–Sze (2nd ed.). Leiden: E. J. Brill. pp. 854–855. ISBN 978-90-04-10422-8.

- Matthee, Rudi (2002). "Gorgin Khan". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XI/2: Golšani–Great Britain IV. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 163–165. ISBN 978-0-933273-62-7.

- Matthee, Rudi; Mashita, Hiroyuki (2010). "Kandahar iv. From The Mongol Invasion Through the Safavid Era". In Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Encyclopædia Iranica, Volume XV/5: Ḵamsa of Jamāli–Karim Devona. London and New York: Routledge & Kegan Paul. pp. 478–484. ISBN 978-1-934283-28-8.

- Matthee, Rudi (2011). Persia in Crisis: Safavid Decline and the Fall of Isfahan. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857731814.

- Matthee, Rudi (2015a). "Solṭān Ḥosayn". Encyclopaedia Iranica.

- Matthee, Rudi (2015b). "The Decline of Safavid Iran in Comparative Perspective". Journal of Persianate Studies. 8 (2): 276–308. doi:10.1163/18747167-12341286.

- Mokhberi, Susan (2019). The Persian Mirror: Reflections of the Safavid Empire in Early Modern France. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0190884802.

- Newman, Andrew J. (2008). Safavid Iran: Rebirth of a Persian Empire. I.B.Tauris. ISBN 978-0857716613.