| Somali | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution | Somalia, Djibouti, Ethiopia, Kenya |

Native speakers | (undated figure of 21 million) |

| Linguistic classification | Afro-Asiatic |

| Proto-language | Proto-Somali |

| Glottolog | None east2653 (East Omo–Tana (partial match)) |

The Somali languages form a group that are part of the Afro-Asiatic language family. They are spoken as a mother tongue by ethnic Somalis in Horn of Africa and the Somali diaspora. Even with linguistic differences, Somalis collectively view themselves as speaking dialects of a common language.[1]

Some neighboring populations and individuals have also adopted the languages. Somali is for instance used as a second language by Girirra.[2]

Overview

Somali variations form a group of East Cushitic languages that are part of the Afroasiatic language family. Their closest relatives are the Aweer and Garre languages, followed by Rendille; this group is sometimes known as Sam or Eastern Omo-Tana. Together with Bayso and the Arboroid languages such as Daasanach, these are known as the Omo-Tana languages. A term "Somaloid" is ambiguous and has been used for either all of Omo-Tana, for the Sam group, or for a group comprising Sam and Baiso.

- Afroasiatic

- Semitic languages, Ancient Egyptian, etc.

- Cushitic

- Beja, Agaw languages, etc.

- East Cushitic

Classification

Somali linguistic varieties are broadly divided into three main groups: Northern, Benadir and Maay. Northern Somali (or Nsom[3]) forms the basis for Standard Somali.[4]

The most extensive publication on the subject is Marcello Lamberti's 'Die Somali-Dialekte'.[5] Both Lamberti (1986) and Blench (2006) separate Central and Benadir into two distinct groups, Digil and Maay and Benadir and Ashraaf, respectively:[6][7]

- Somali

- Northern

- Benadir

- Ashraaf

- Maay

- Digil

Northern

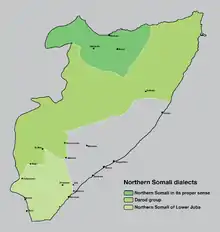

Northern Somali is spoken by more than 70% of the entire Somali population.[3] Its primary speech area stretches from Djibouti, Somaliland and to parts of the eastern and southwestern sections of Somalia.[8] This widespread modern distribution is a result of a long series of southward population movements over the past ten centuries from the Gulf of Aden littoral.[9] Northern Somali is subdivided into three dialects: Northern Somali proper (spoken in the northwest), the Darod group (spoken in the northeast and along the eastern Ethiopia frontier), and the Lower Juba group (spoken by northern Somali settlers in the southern riverine areas).[3] Northern Somali has frequently been used by famous Somali poets as well as the political elite, and thus has the most prestige out of the Somali dialects.[10] Due to being wide spread, it forms the basis for Standard Somali.[11] Most of the classical Somali poetry is recited and composed in the Northern Somali dialect.[3]

Lamberti divides Northern Somali into three subgroups:[7]

- Northern Somali proper: spoken in the countries of Djibouti and Somaliland (Awdal, Maroodi Jeex, Saaxil, Togdheer, Sanaag and Sool). The dialects belonging to this group are the Issa, Gadabuursi, Isaaq and the Darood, (Warsangeli and Dulbahante). The greatest number of speakers overall.

- Darod group: spoken in the regions of Bari, Nugal, Mudug, in the Somali Region of Ethiopia and along the Ethiopian border in the regions of Galguduud, Bakool and Gedo. The dialects of this group are the North-Eastern dialects (Marehan,Warsangeli, Dulbahante, Majeerteen, and Ogaden).

- Lower Juba group: spoken by the part of the Northern Somali population which have immigrated into the Lower Juba region in the last 100/150 years. As this territory was a Benaadir-speaking area before the arrival of the immigrants from the north, the Nsom of Lower Jubba presents many peculiarities typical for the Benaadir dialects and could be considered a Benaadirised Nsom.

Coastal

Coastal Somali (also grouped as Benadir and Ashraf) is spoken on the Benadir coast from Hobyo to south of Merca, including Mogadishu and in the hinterland.[6]

- Coastal:[7]

- Benadiri

- Northern

- Southern

- Ashraaf

- Shingani

- Lower Shabbelle

- Benadiri

Central

Central Somali (also grouped as Digil and Maay) is spoken in the inter-riverine regions of Somalia by the Digil and Mirifle clans, collectively known as the Rahanweyn Somalis.[6] They are most often described as dialects[6] Others regard them as being divergent from the latter as Spanish is to Portuguese.[12] Of the Central variations, Jiddu is the most incomprehensible to Benadir and Northern speakers.[6]

Other

In addition, Kirk (1905) reports Yibir and Midgan, spoken by the Yibir and Madhiban, respectively. Blench (2006) says, "These lects, spoken respectively by magicians and hunters among the Somali are said to differ substantially in lexicon from standard Somali. Whether this differentiation is in the nature of a code or these represent distinct languages remains unknown."

Other groupings

Ehert & Ali (1984) classifications represents a sharp contrast to that of the rest. They classify these variation into three main groups in a more genealogically focused approach:[13]

- Soomaali

Jiiddu in this model is relocated as not even a Somali sensu lato variety in origin, but instead as a sibling of Bayso.[13] In contrast, Garre shows quite close affinity to Aweer, a language spoken by the physically and culturally distinct Aweer people.[14][15] Evidence suggests that the Aweer/Boni are remnants of the early hunter-gatherer inhabitants of Eastern Africa. According to linguistic, anthropological and other data, these groups later came under the influence and adopted the Afro-Asiatic languages of the Eastern and Southern Cushitic peoples who moved into the area.[16]

Reconstruction

Proto-Somali has been reconstructed by Biber (1982).[17]

References

- ↑ Somali nationalism: international politics and the drive for unity in the Horn of Africa. Department of Linguistics and the African Studies Center, University of California, Los Anglos. 1963. p. 24. ISBN 9780674818255.

- ↑ Somali at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- 1 2 3 4 Lamberti, Marcello (1986). Map of Somali dialects in the Somali Democratic Republic (PDF). H. Buske. ISBN 9783871186905.

- ↑ Dalby, Andrew (1998). Dictionary of languages: the definitive reference to more than 400 languages. Columbia University Press. p. 571.

- ↑ Somalia: Language situation and dialects (PDF). Landinfo. 2011. p. 5., Quote: "Lamberti surveyed Somali dialects during a field study in Somalia in 1981. He completed his studies in Mogadishu, Bardheere and Luuq in the Gedo region; Saakow, Jilib and Bu'aale in Middle Juba; Merka and Qoryoley in Lower Shebelle; Qansax Dheere, Baidoa, Dinsor, Yaaq Baraaway and Bur Hakaba in the Bay Region; Jamaame and Kismayo in Lower Juba, as well as Adalar in Middle Shebelle (1986a, p. 15). Martin Orwin stresses that no systematic field studies of the Somali dialects have been carried out since the 1980's."

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Report Somalia: Language situation and dialects" (PDF). Country of Origin Information Centre (Landinfo). 2011. p. 6.

- 1 2 3 4 Blench, Roger (2006). "The Afro-Asiatic Languages: Classification and Reference List" (PDF). p. 3.

- ↑ Mundus, Volumes 23-24. Wissenschaftliche Verlagsgesellschaft. 1987. p. 205.

- ↑ Andrzejewski, B.; Lewis, I. (1964). Somali poetry: an introduction. Clarendon Press. p. 6.

- ↑ Saeed, John (1999). Somali. Amsterdam: John Benjamins. p. 5. ISBN 1-55619-224-X.

- ↑ Ammon, Ulrich (2006). Sociolinguistics: An International Handbook of the Science of Language and Society, Part 3. Walter de Gruyter. p. 194. ISBN 9783110184181.

- ↑ Lewis, I. M. (1 January 1998). Saints and Somalis: Popular Islam in a Clan-based Society. The Red Sea Press. p. 74. ISBN 9781569021033.

- 1 2 Tosco, Mauro (1994). "The Historical Reconstruction of a Southern Somali Dialect: Proto-Karre-Boni". Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika. 15: 153–209.

- ↑ Aweer at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ↑ Garre at Ethnologue (25th ed., 2022)

- ↑ Mohamed Amin, Peter Moll (1983). Portraits of Africa. Harvill Press. p. 16. ISBN 0002726394.

- ↑ Douglas Biber. 1982. The phonological system of proto-Somali. Los Angeles: University of Southern California.