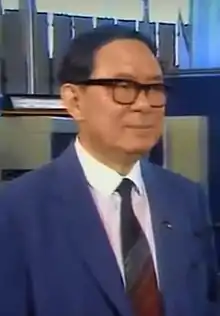

Song Jian | |

|---|---|

| 宋健 | |

Song jian 1989 | |

| State Councilor of the People’s Republic of China | |

| In office 1986–1998 | |

| Premier | Zhao Ziyang→Li Peng |

| Director of the State Science and Technology Commission | |

| In office 1985–1998 | |

| Preceded by | Fang Yi |

| Succeeded by | Zhu Lilan |

| President of the Chinese Academy of Engineering | |

| In office 1998–2002 | |

| Preceded by | Zhu Guangya |

| Succeeded by | Xu Kuangdi |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 29 December 1931 Rongcheng, Shandong, China |

| Political party | Chinese Communist Party |

| Alma mater | Harbin Institute of Technology, Beijing Foreign Language Institute, Moscow State University, Bauman Moscow State Technical University |

Song Jian (Chinese: 宋健; Wade–Giles: Sung Chien; born 29 December 1931) is a Chinese aerospace engineer, demographer, and politician. He was deputy chief designer of China's submarine-launched ballistic missile (JL-1) and one of the country's leading scientists in the post-Cultural Revolution era. After a decade of two-child restrictions in the 1970s, and following the Chinese government's announcement in 1979 to advocate for one child per family, he became a leading advocate for rapid implementation and broad coverage of China's one-child policy.[1][2][3][4] He served in high-ranking political positions including Vice Minister of Aerospace Industry, Director of the State Science and Technology Commission (1985–1998), vice-premier-level State Councillor (1986–1998), President of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, Vice Chairperson of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference, and a member of the Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party.

Early life and education

Song Jian was born on 29 December 1931 in Rongcheng, Shandong Province.[5][6] In 1946, he enlisted in the Chinese Communist Party's Eighth Route Army during the Chinese Civil War at the age of 14.[7]

After the establishment of the People's Republic of China in 1949, he studied at Harbin Institute of Technology and Beijing Foreign Language Institute,[8] before being sent to the Soviet Union in 1953 on the recommendation of Liu Shaoqi, Vice Chairman of China.[7] Described as a "brilliant" student, he studied cybernetics and military science under the theorist A. A. Feldbaum. He earned an associate Ph.D. degree from Moscow State University[7] and a Ph.D. from Bauman Moscow State Technical University.[6] He published seven papers in Russian on control theory, which won praise from Soviet and American scientists.[7]

Career

After the Sino-Soviet split in 1960, Song returned to China and was put in charge of control systems at the Fifth Academy (later known as the Seventh Ministry of Machine Building or Missile Ministry) of the Ministry of National Defense. He was one of China's top experts on missile guidance systems. Qian Xuesen, the "father of China's space and missile defence programs", highly praised Song's ability and declared that Song was China's foremost control theorist, surpassing Qian himself. Qian personally chose Song to co-author the revised edition of his Engineering Cybernetics, regarded as a bible of Chinese military science.[9]

At the beginning of the Cultural Revolution, Song's home was ransacked by the Red Guards before Premier Zhou Enlai included him in the list of top 50 scientists considered indispensable to national defence and afforded special protection. Song was sent to the Jiuquan Satellite Launch Center in the desert where he could focus on his studies and research, before returning to Beijing in 1969. His work on anti-ballistic missiles attracted Zhou's attention.[10]

In the late 1970s, Song applied his expertise in cybernetics to the problem of population control and became a proponent of China's so-called one-child policy.[11] At the same time, he continued to work in the missile and aerospace programs and rapidly ascended the political hierarchy. He was appointed deputy chief designer of JL-1, China's submarine-launched ballistic missile in February 1980 (under Huang Weilu), and Vice Minister of Aerospace Industry in 1982.[12] In 1985 he became Director of the powerful State Science and Technology Commission, and the next year he additionally became a State Councillor, a vice-premier-level position. He held both positions until 1998,[8][12] when he was appointed President of the Chinese Academy of Engineering and Vice Chairperson of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).[8]

Song was an alternate members of the 12th Central Committee of the Chinese Communist Party, and a full member of the 13th, 14th, and 15th central committees.[8]

One-child policy

After the end of the Cultural Revolution, Premier Zhou Enlai announced in 1970 a five-year plan that called for population growth targets in light of Malthusian concerns that a rapidly growing population would derail China's economic development. That program evolved into a two-child policy for the rest of the 1970s. Thereafter, China's new leader Deng Xiaoping continued this program, reducing military spending and urging scientists to focus their energy on solving the country's urgent economic problems, including widespread poverty.[13] In 1978, as China made its initial announcement to tighten the restrictions to one child per family, Song attended the Seventh World Congress of the International Federation of Automatic Control in Helsinki, Finland, where he encountered the cybernetic-based population control theory associated with the Club of Rome. He saw the theory as a precise and scientific approach to the population control problem, which seemed superior to the Marxist perspectives that had long predominated in China.[11]

Based on assumptions of future trends, Song and his group performed calculations that determined the "ideal" population for China in the next 100 years was 650 to 700 million, about two-thirds of its then-population of 1 billion. In order to achieve this long-term environmentally sustainable population, he showed that the "optimal" trajectory was to reduce fertility rapidly to one child per couple by 1985 and maintain that level for 20 to 40 years, and then slowly raise it to the replacement level (2.1 children per woman).[14]

Following the Chinese central government's decision to advocate for one-child families in 1979, Song and his associates entered the picture, actively supporting and promoting the one child ideal through conference discussions in 1980 in Chengdu. They presented their work to members of the Chinese Academy of Sciences,[15] and through the country's top scientists, came to the attention of, and won support of, China's top leaders for rapid implementation and broad coverage of one-child limits. Song's work was endorsed by Vice Premiers Chen Muhua[16] and Wang Zhen,[17] who recommended it to Chen Yun, the second most influential official after Deng Xiaoping. Shocked by Song's population projections, the highest of which projected China's population to reach 4 billion by 2080 if women continued to have three births per woman, China's leaders were convinced that rapid adoption of a near universal one-child policy was the country's only option if it wanted to meet Song's population targets.[17] Although some leaders, including Zhao Ziyang and Hu Yaobang, expressed doubts about its feasibility, at a top-secret high-level meeting convened in April 1980 Song won over many policymakers to his recommendation of universal one-child limits.[18] In September, the third session of the 5th National People's Congress approved the policy.[19]

Although it is widely agreed that Song's population projections influenced the speed and scope of implementation of one-child limits, several leading scholars have refuted Greenhalgh's thesis that Song "hijacked the population policymaking process" [20] and that he should be considered both the inventor and central architect of the one-child policy, a thesis that has often been regurgitated without much critical reflection.[4][21][22] Liang Zhongtang, who participated in the critical policy discussions in Chengdu in 1980 and emerged as the foremost internal critic of one-child limits, confirms that Greenhalgh put too much emphasis on Song and his group.[4] Wang et al. agree, concluding that "the idea of the one-child policy came from leaders within the Party, not from scientists who offered evidence to support it.".[23] Goodkind suggests that Song and his colleagues were "more like expert witnesses for a government already determined to prosecute one-child restrictions, taking advantage of the opportunity to become players in a vast and expanding government bureaucracy"[24] Indeed, upon learning of Song's work in February 1980, correspondence from Wang Zhen, Chen Muhua, and other top officials[20] suggests that they were already highly sympathetic to Song's position.

It is also important to note that the universal one-child limits advocated by Song lasted only five years. In the mid 1980s, China began to permit exemptions for rural parents whose first child was a daughter (an exemption allowed due to the unpopularity of the universal one-child rule), which, along with other exemptions, resulted in a "1.5-child" policy that lasted for nearly 30 years. Thus, the policy in place since the mid 1980s that has been commonly referred to as "the one-child policy" was actually a less restrictive policy, the very sort that China might have adopted in 1980 even without the population projections and cybernetic models of Song and his colleagues.

Other programs

As the director of the State Science and Technology Commission, Song was in charge of China's science and technology policies. He oversaw the Spark Program, which aims to popularize scientific knowledge and technology to benefit common people, the Torch Program, which encourages scientists to commercialize their scientific discoveries, and the 863 Program, which aims to stimulate the development of high-tech research in China. He also launched the Xia–Shang–Zhou Chronology Project to determine a more accurate chronology of the earliest dynasties in Chinese history.[25]

Honours and awards

Song Jian is an academician of both the Chinese Academy of Sciences and the Chinese Academy of Engineering. He is a foreign member of the US National Academy of Engineering, the Russian Academy of Sciences, and the Royal Swedish Academy of Engineering Sciences. He is also a member of Euro-Asian Academy of Sciences and the International Academy of Astronautics.[5]

References

- ↑ Tien, H.Y. (1991). China's Strategic Demographic Initiative. New York: Praeger.

- ↑ Scharping, Thomas (2003). Birth control in China 1949–2000: Population policy and demographic development. London: Routledge.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 253.

- 1 2 3 Hvistendahl (2010), p. 1460.

- 1 2 Lu (2006), p. 41.

- 1 2 "Song Jian" (in Chinese). Chinese Academy of Sciences. Archived from the original on 11 December 2018. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- 1 2 3 4 Greenhalgh (2008), p. 128.

- 1 2 3 4 "Song Jian" (in Chinese). Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference. Retrieved 17 January 2018.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2008), p. 129.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2008), p. 130.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh (2005), p. 259.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh (2005), p. 260.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 258.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 266.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 269.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 270.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh (2005), p. 271.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 272.

- ↑ Greenhalgh (2005), p. 273.

- 1 2 Greenhalgh (2005), p. 269-270.

- ↑ Zubrin, Robert (2012). "Radical Environmentalists, Criminal Pseudo-Scientists, and the Fatal Cult of Antihumanism". The New Atlantis. 2646.

- ↑ Fong, Mei (2016). One child: The story of China's most radical experiment. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Harcourt.

- ↑ Wang, Feng; Cai, Yong; Gu, Baochang (2013). "Population, policy, and politics: How will history judge China's one-child policy?". Population and Development Review. 38 (Suppl. 1): cite p.119–120. doi:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00555.x. hdl:10.1111/j.1728-4457.2013.00555.x.

- ↑ Goodkind, Daniel (2018). "If Science Had Come First: A Billion Person Fable for the Ages (A Reply to Comments)". Demography. 55 (2): cite p.762–763. doi:10.1007/s13524-018-0661-z. PMID 29623609.

- ↑ "Song Jian: a leading scientist". China Daily. 2008. Archived from the original on 2018-01-19. Retrieved 2018-01-19.

Bibliography

- Greenhalgh, Susan (June 2005). "Missile Science, Population Science: The Origins of China's One-Child Policy". The China Quarterly. 182 (182): 253–276. doi:10.1017/S0305741005000184. JSTOR 20192474. S2CID 144640139.

- Greenhalgh, Susan (2008). Just One Child: Science and Policy in Deng's China. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-25338-4.

- Hvistendahl, Mara (17 September 2010). "Of Population Projections and Projectiles". Science. 329 (5998): 1460. Bibcode:2010Sci...329.1460H. doi:10.1126/science.329.5998.1460. PMID 20847245.

- Lu, Yongxiang (7 April 2006). Science Progress in China. Elsevier Science. ISBN 978-0-08-054079-5.