| Spangen Castle | |

|---|---|

Kasteel ter Spangen | |

| Near Overschie, Rotterdam, the Netherlands | |

%252C_RP-P-OB-73.492.jpg.webp) Spangen before 1574, etching by Abraham Rademaker from about 1730 | |

Spangen Castle | |

| Coordinates | 51°55′38″N 4°25′31″E / 51.927328°N 4.425228°E |

| Type | Castle |

| Site information | |

| Open to the public | No |

| Condition | disappeared |

| Site history | |

| Built | 13th century |

| Demolished | burned in 1574 |

Spangen Castle (also known as ter Nesse) was a medieval castle near the village Overschie. It has disappeared completely. The Rotterdam city quarter Spangen was named for the castle.

Castle Characteristics

Disappearance and excavation

The last visible remains of Spangen Castle disappeared in the second half of the nineteenth century. A Mr. Looys then made a floor plan from what he saw.[1]

In 1942 Spangen Castle was excavated, because an inland harbor for Rotterdam would be constructed in the area. The excavation was led by Jaap Renaud of the Rijksdienst voor de Monumentenzorg. The idea to investigate Rotterdam's antiquities was promoted by Johan Ringers.[2][3][4]

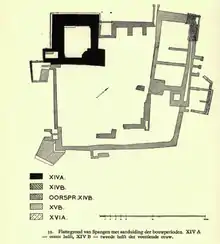

Phase I: The tower house

The early fourteenth century tower house was the oldest part of the castle. On the floor plan it is marked with XIVA. The tower house was remarkable for having over 2 meter thick walls on the moat sides, and much thinner ones on the court side. The idea was probably to first defend the court side only with an earth breastwork along its moat, and to extend the stone structure later on.[5]

The court side corner of the tower house had a wide protruding foundation. It was probably the foot of a stair tower, because the inner walls were too thin to contain stairs. On the southwest side of the tower house, a privy (tower) extended into the moat. Its exit was topped by masonry arc. Later the opening was closed by a woven matt of withy, perhaps against rats.[5]

Phase 2: a brick wall is added

In the second construction phase a stone wall was built around the court, see map XIVB and Oorspr. XIVB. Next to the tower house was the gate.[5] The gate had two openings on the moat side (see map), probably for heavy beams that were part of the draw bridge. In the moat two poles were found, that would have supported the bridge. At 20 m outside the gate, the bridgehead was found, albeit from masonry of the last period that the castle was inhabited.[6]

East of the gate a small stretch of an enceinte started, showing its character by the buttresses that supported a protected walkway. Next was probably a tower on the north tip of this castle, but this could not be proven. From the same time dates a wall on the northeast side. Parts of this wall were later integrated as southwest wall of a new northeast wing. This first wall is not a complete square on the floor plan, because some southeastern parts of this wall were not recovered during the excavations. [6]

Phase 3

The third construction phase (XVB) started by filling the northeast and southeast part of the moat. A new northeast wing was then built where part of the moat had been. On its northwest and northeast side the wing had a new heavy cavity wall, a very rare concept in medieval times. On the southern tip of the new wing was a high stair tower, displayed on many pictures of the (ruined) castle. At the new northern tip of the castle, the foundations were gone, and only foundation piles were present. This allowed to extract some of these piles, which proved to be about 4 m long, and to have rested on a layer of clay.[6]

On the southeast tip of the new wing was an adjoining square well about halfway the new northeast wall. The still existing part was 2 m high, and had a wooden floor. From the well, the wall of the new wing then continued to the southeast as a regular defensive wall without cavity. From the new eastern tip of the castle this wall the ran southeast, until making a 90 degree turn on the southern tip, and running for about three meters to connect to the wall of the second phase.[6]

Building on top of a filled up body of water is unusual, because it's dangerous. Renaud therefore dug a trench under the northeast wing, which indeed confirmed that it stood on top of a former moat. A trench south of the well gave the same result.[6] A shoring had been built about half a meter outside of the foundations in order to give some stability to the filled up area.[7]

Phase 4: Annexes

The last construction phase (XVIA) added some annexes to the castle. On the northeast side an annex was built that would later cave in so seriously that its wall broke, see photo.[7]

On the southern corner was a construction that Looys saw as a buttresses. Renaud judged it to have been a bastion.[7]

Brickwork

In general, medieval construction used different kinds of stone and brick at different times. This allows researchers to roughly date (parts of) medieval buildings. This was also the case at Spangen Castle. The archaeologist Jaap Renaud was quite fond of describing the different types of brick he found at castles. At Spangen he judged that circumstances were ideal to date parts of the castle after the brick that had been used.[8]

The tower house, or keep was made of red brick of 31 * 15 * 7 cm. The brick used in the second construction phase was generally pale-red, with yellow parts and veins. It measured 26 * 13 * 6 cm, while some bricks were 25 and others 27 cm long.[8]

In the third phase, a pale-red brick of a relatively high hardness was used. It measured about 22 * 10 * 5 cm. The third phase saw some reuse. When the northeastern wing was built, a part of the second phase northwestern wall was broken down. Bricks from this wall were then reused in the foundations of the new extension. The fourth phase used a typical yellow hard brick, which Renaud called IJsselsteen (IJssel brick). It measured 18 * 8.5 * 4 cm.[8]

History

Uytter Nesse

The first known ancestor of the lords of Spangen Castle was Philips Uytter Nesse.He was married to Sophia van Dorp, and mentioned in 1307. In 1309 Philips (Voernesse) is included in the verdict of the killing of Wolfert van Borselen at Delft in 1299.[9]Philip is last mentioned in 1316.[10]

Van Spangen

In 1322 Jan van der Nesse had a fief of land in Schieambacht. He was probably a son of Philip. At the same time Dirk Bokel Uytter Nesse was head of the clan. In 1323 Dirk Bokel was granted in fief 47 morgen of land on the small river Spange by Sir Gerard van Heemskerk. From this 47 morgen Dirk kept 27 apart that would become the core of the arrear-fief Spangen. In 1325 a Jan van der Spange was mentioned. It can therefore be supposed that Jan van der Nesse got the 27 morgen of land, grounded the castle, and styled himself Jan van der Spange. This theory is supported by the pottery findings on site.[11]

Jan van der Spangen was probably rather poor, and dependent on serving the count for income. In 1336 he was mentioned as bailiff of Schiedam. He would have died somewhere between 1336 and 1343. In 1343 Philip van Spangen managed the family estate. He already died in 1343 or 1344.[12] A payment in 1346 shows that in that Dirk van Spangen was lord of the manor.[13] Because of time constraints, Dirk was probably the younger brother of Philip. Dirk was married to Maria van Sevenbergen and lived till about 1380.[14]

Hook and Cod Wars

Dirk van Spangen's role during the Hook and Cod Wars is important to determine what might have happened to the castle in 1351, the year the civil war started in earnest.[14] Squire Dirk van Spangen was on the list of members of the Hook Alliance.[15] Symon van der Sluys therefore claimed that Spangen Castle had been destroyed by the Cod party in 1351.[16] Others claim that none of the Hook castles in the area was besieged, and that they were simply handed over and demolished without a fight.[17]

Renaud thought it possible that Spangen was burned in 1351 like nearby Te Riviere Castle was, but thought this not that likely. Daniël van Mathenesse and Dirk were both on the count's side in 1352.[18] While Daniël was later compensated for a fire, Dirk was not. Renaud also mentioned that Dirk might have drawn conclusions from what happened at Te Riviere, and quickly switched to the other side. Dirk's son Jan continued to oppose the count but might have been in the opposing army.[14]

In 1359 those of Delft might have attacked Spangen Castle, but that's not at all sure. The second phase of the construction of Spangen Castle probably dates from the later part of Dirk's rule.[19]

Philip van der Spangen

Dirk's son Jan must have died between 1372 and 1380, before his father died. In 1381 his younger brother Philip succeeds Dirk. He married Lijsbeth, daughter of Gijsbrecht van IJsselsteyn. Philip was very successful. During the struggle between Jacqueline of Bavaria and Philip of Burgundy (1417-1432), Philip held several commands.[19]

In 1424 Philip was succeeded by his son Egbert, though this year is not sure. The idea that Willem Nagel destroyed Spangen Castle would be illogical, because Egbert was on Jacqueline's side.[20]

In 1452 Egbert's son Philip inherited Spangen Castle. He was probably responsible for the big phase 3 reconstruction.[20] During the Jonker Fransen War (1488-1490), the States of Holland garrisoned Spangen Castle. It was not taken by the troops of Frans van Brederode, but the damage caused by the garrison was substantial.[21]

Philip (III) died about 1508, and was succeeded by his son Philip (IV). In 1530 Philip IV was succeeded by his brother Cornelis.[21]

Destruction

During the opening phases of the Eighty Years' War, the Van der Spangen family would move to the Southern Netherlands.[22]

In 1572, Spangen Castle was occupied by the Geuzen under the Count of Lumey. In the same year the castle was destroyed by a group from Delft. When the Royalist Army conquered it in 1574, it decided to burn it down to prevent further occupation. The castle was not rebuilt afterwards.

The ruins and Pictures of the ruins

The ruined castle

The ruins of Spangen Castle proved quite durable. They were the subject of many drawings and engravings. Some of these depicted the castle as it would have been before 1574. The engraving by Hondius might be the oldest depiction of the castle. The artist and architect Jacob Lois (c. 1620–1676) [23] made several drawings, and even a more or less accurate floor plan of the castle in 1670. He put these in a manuscript.[24] These drawing seem to have been used by F. Baudouin to make the double engraving showing the castle in prosperity and in ruins.

Series by Rademaker

The series by Abraham Rademaker (1677–1735) is rare, because it depicts the castle from many sides. No. 139 and 140 are inline with Baudouin's engravings. No 141-144 seem conjecture based on these, and do not fit very well with Renaud's findings. How Rademaker came to depict the cavity wall on No 142 is not yet clear.

%252C_RP-P-OB-73.492.jpg.webp) Rademaker No 139 'Spangen before destruction' from the northwest (front)

Rademaker No 139 'Spangen before destruction' from the northwest (front)%252C_RP-P-OB-73.493.jpg.webp) Rademaker No 140 'Spangen in Ruins' from the northwest (front)

Rademaker No 140 'Spangen in Ruins' from the northwest (front)%252C_RP-P-OB-73.494.jpg.webp) Rademaker No 141 Spangen from the northwest (front)

Rademaker No 141 Spangen from the northwest (front)%252C_RP-P-OB-73.495.jpg.webp) Rademaker No 142 Spangen from the north

Rademaker No 142 Spangen from the north%252C_RP-P-OB-73.496.jpg.webp) Rademaker No 143 Spangen from the west

Rademaker No 143 Spangen from the west%252C_RP-P-OB-73.497.jpg.webp) Rademaker No 144 Spangen from the south

Rademaker No 144 Spangen from the south

References

- Brugmans, Hajo (1924), "Lois, Jacob", Nieuw Nederlandsch biografisch woordenboek, Sijthoff's, Leiden, vol. VI, p. 962

- Hoek, C. (1975), "Schiedam. Een historisch-archeologisch stadsonderzoek" (PDF), Holland, regionaal-historisch tijdschrift, Historische Vereniging voor Zuid-Holland, no. 2, pp. 89–196

- Lois, Jacob Lois (1672), Oude Ware Beschrivinge van Schielandt ... ende nu beschreven en bijeen gestelt door Jacob Lois ... tot in den jaare 1672 toe, None, manuscript, pp. 58–59

- Van Mieris, Frans (1754), Groot charterboek der graaven van Holland, van Zeeland, en heeren van Vriesland, vol. II, Pieter vander Eyk, Leyden

- Prevenier, W.; Smit, J.G. (1991), Bronnen voor de geschiedenis der dagvaarten van de Staten en steden van Holland, vol. I, Instituut voor Nederlandse Geschiedenis

- Renaud, J.G.N. (1942), "Oudheidkundige onderzoekingen in en om Rotterdam", Rotterdams Jaarboekje, Stadsarchief Rotterdam, pp. 121–151

- Renaud, J.G.N. (1943), "Spangen en de van der Spangen's", Rotterdams Jaarboekje, Stadsarchief Rotterdam, pp. 203–212

- Renaud, J.G.N. (1943d), "Ontdekkingstocht door middeleeuws Rotterdam", De Maastunnel te Rotterdam, N.V. Maastunnel, pp. 214–223

Notes

- ↑ Renaud 1942, p. 142.

- ↑ Renaud 1942, p. 121.

- ↑ Renaud 1942, p. 141.

- ↑ Renaud 1942, p. 150.

- 1 2 3 Renaud 1942, p. 143.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Renaud 1942, p. 144.

- 1 2 3 Renaud 1942, p. 145.

- 1 2 3 Renaud 1942, p. 147.

- ↑ Van Mieris 1754, p. 83.

- ↑ Renaud 1943, p. 204.

- ↑ Renaud 1943, p. 205.

- ↑ Renaud 1943, p. 206.

- ↑ Renaud 1943, p. 207.

- 1 2 3 Renaud 1943, p. 208.

- ↑ Prevenier & Smit 1991, p. 76.

- ↑ Renaud 1943, p. 203.

- ↑ Hoek 1975, p. 178.

- ↑ Van Mieris 1754, p. 809.

- 1 2 Renaud 1943, p. 209.

- 1 2 Renaud 1943, p. 210.

- 1 2 Renaud 1943, p. 211.

- ↑ Renaud 1943, p. 212.

- ↑ Brugmans 1924, p. 962.

- ↑ Lois 1672, p. 58.