Spiridon Спиридон | |

|---|---|

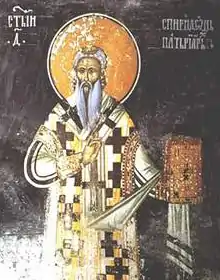

Fresco of Spiridon from the Serbian Orthodox Patriarchal Monastery of Peć (ca. 1396) | |

| Serbian Patriarch | |

| Venerated in | Eastern Orthodox Church |

| Church | Serbian Orthodox Church |

| Metropolis | Serbian Patriarchate of Peć |

| See | Patriarchal Monastery of Peć |

| Installed | after 3 May 1380[1] |

| Term ended | 1389 |

| Predecessor | Jefrem |

| Successor | Jefrem |

| Personal details | |

| Born | |

| Died | 11 August 1389 Serbia |

| Buried | Patriarchal Monastery of Peć |

| Denomination | Eastern Orthodoxy |

| Residence | Žiča |

| Sainthood | |

| Feast day | 11 August |

Spiridon (Serbian Cyrillic: Спиридон; fl. 1379–d. 11 August 1389) was the Patriarch[a] of the Serbian Patriarchate of Peć from 1380 to 1389.[2] He held office during the reign of Prince Lazar, who was recognized by the Serbian Church as the legitimate ruler of the Serbian lands (in the period of the Fall of the Serbian Empire), and with whom he closely cooperated.

Spiridon was chosen to succeed Patriarch Jefrem, who abdicated, in 1379,[3] and was enthroned after 3 May 1380.[1] Historian M. Petrović believes that Jefrem abdicated due to opposing the politics of suppressing the jurisdiction of the Patriarchate of Constantinople, which was pursued by Prince Lazar and Spiridon.[4] The Serbian Church recognized Lazar as the legitimate ruler of the Serbian lands, the autokrator (inherited by the Nemanjić dynasty), since 1375.[3] Spiridon's life prior to enthronement is unclear. He is believed to have been born in Niš, as written in the old list of Serbian patriarchs (Патріархъ Спиридонъ родомъ отъ Нишъ[5]), accepted in early Serbian literature, however, there is no confirmation.[6] M. Purković assumed that Spiridon was a bishop of perhaps Caesaropolis, then the metropolitan of Melnik. Two acts from Vatopedi dating to October 1377 mention a "metropolitan Spiridon".[7] Spiridon might have been the same as the Dečani ascetic Spiridon; Jefrem chose Spiridon as his successor, his close friend, fellow clergyman, and venturer, a hesychast as himself, and also a man of the court – respectable, educated, and informed on the secrets and state skills and church politics, more than Jefrem himself.[8] Historian M. Spremić believed that Jefrem had in the first place been enthroned as a compromise between the Serbian Church and the Patriarchate of Constantinople, and that he was forced to abdicate by followers of Prince Lazar.[4]

Spiridon was a close associate of Lazar,[9] and their work coincided – the renewal of the Nemanjić ideal of symphony of the state and church.[10] The patriarch was the most important person along with the ruler, whom he versatilely supported.[11] Spiridon confirmed Lazar's 1378 charter to Gornjak (Ždrelo), Lazar's endowment, and Lazar's 1387 charter to Obrad Dragosalić.[12] On 2 March 1382, in Žiča, the founding charter of the Drenče monastery was written before Spiridon.[13] Spiridon died on 11 August 1389 (as recorded in Danilo's typikon from 1416), not long after the Battle of Kosovo in which Lazar fell.[1] After Lazar's death, Spiridon stayed in alliance with Lazar's widow Milica.[14] After the battle and Spiridon's death, the security of the Serbian state and church was threatened by the Ottomans; Milica's political circle worked to establish peace with the Ottomans, a deal which was eventually struck with large Serbian concessions, by the summer of 1390.[15] Spiridon was succeeded by Jefrem, who returned and served shortly until he was replaced by Danilo III.[16]

In the Serbian epic film Battle of Kosovo (1989), Spiridon was played by actor Miodrag Radovanović.[17]

Annotations

References

- 1 2 3 Radojičić 1952, p. 86.

- ↑ Purković 1976, p. 116.

- 1 2 Gavrilović 1981, p. 16.

- 1 2 Popović 2006, p. 119.

- ↑ Glas Srpske akademije nauka. Štampa jugoslavskog štamparskog preduzeća. 1949. p. 111.

- ↑ Purković 1976, p. 117.

- ↑ Purković 1976, p. 118.

- ↑ Hilandarski odbor 1978, p. 126.

- ↑ Gavrilović 1981, p. 16; Pavle of Serbia 1989, p. 100

- ↑ Marjanović-Dušanić 2006, pp. 83–84.

- ↑ Sava of Šumadija 1996, p. 465.

- ↑ Radojičić 1952, pp. 87–89.

- ↑ Purković 1976, p. 119.

- ↑ Marjanović-Dušanić 2006, p. 84.

- ↑ Gavrilović 1981, p. 109.

- ↑ Radojičić 1952, pp. 88–89.

- ↑ Boj na Kosovu (1989) at IMDb

- ↑ Purković 1976, p. 26.

- ↑ Pavle of Serbia 1989, p. 101.

Sources

- Books

- Gavrilović, Slavko (1981). Istorija srpskog naroda. Vol. 2. Srpska književna zadruga. pp. 11, 13, 16, 48, 109–110, 166, 174, 177.

- Pavle of Serbia (1989). Sveti Knez Lazar: Spomenica o šestoj stogodišnjici Kosovskog boja : 1389-1989. Izd. Svetog arhijerejskog sinoda Srpske pravoslavne crkve.

- Purković, Miodrag (1976). Srpski patrijarsi Srednjega veka. Srpska pravoslavna eparhija zapadnoevropska. pp. 26, 116–120.

- Sava of Šumadija (1996). Srpski jerarsi: od devetog do dvadesetog veka. Evro.

- Journals

- Hilandarski odbor (1978). Хиландарски зборник. Vol. 4. SANU.

- Marjanović-Dušanić, Smilja (2006). "Dinastija i svetost u doba porodice Lazarević: stari uzori i novi modeli". Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta. Belgrade (43): 77–95.

- Milojević, Srbobran (1987). "Musići". Историјски часопис. Istorijski institut (33): 13–14. GGKEY:580S3RBJUZP.

- Popović, Danica (2006). "Патријарх Јефрем – један позносредњовековни светитељски култ". Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta. Belgrade (43): 111–125.

- Radojičić, Đ. Sp. (1952). "Grigorije iz Gornjaka". Историјски часопис. Istorijski institut (3): 85–106. GGKEY:73HS377YS6Y.