| Stoneyetts Hospital | |

|---|---|

| NHS Greater Glasgow | |

Stoneyetts Hospital grounds, 1992 | |

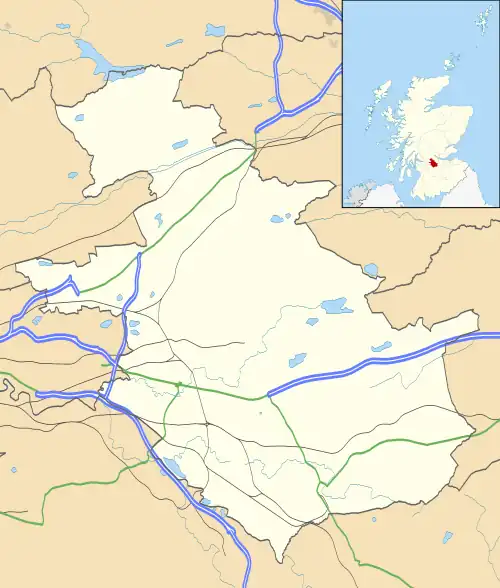

Location within what is now North Lanarkshire | |

| Geography | |

| Location | Gartferry Road, Moodiesburn, Scotland |

| Coordinates | 55°55′08″N 4°05′23″W / 55.9188°N 4.0897°W |

| Organisation | |

| Care system | NHS Scotland |

| Type | Psychiatric hospital |

| Services | |

| Beds | 340 (1954) 180 (1991) |

| History | |

| Opened | 6 June 1913 |

| Closed | 19 February 1992 |

| Links | |

| Lists | Hospitals in Scotland |

Stoneyetts Hospital (also Stoneyetts Certified Institution for Mental Defectives) was a psychiatric hospital located in Moodiesburn, near Glasgow. Opened in 1913, Stoneyetts served as an important source of employment for residents within the expanding Moodiesburn area. The function of the institution changed throughout its existence: it originally cared for those with epilepsy, before housing people with intellectual disability, and from 1937 treating those with mental disorders. By the early 1970s there was an emphasis toward psychogeriatric care at the hospital.

Complaints against Stoneyetts began to surface in the mid 1980s, preceding its controversial closure and demolition in 1992. The brownfield site lay derelict for the next 28 years, becoming a popular location for dog walking, but also for anti-social behaviour. It was redeveloped as a private housing estate in 2020.

History

Stoneyetts was chartered in 1910[1] and designed by Glasgow Parish Council's Master of Works, Robert Tannock, with the foundation stone being laid by council chairman James Cunningham on 23 May 1912. The hospital was built on a 46½ acre site, purchased by the council from the District Lunacy Board, at East Muckcroft within the "Woodilee estate"; the total cost of the project was £45,000 (including a cost of £70 per bed).[2] Gartferry Road in Moodiesburn, a then-expanding local community, would become the hospital's official location.[3][4][5][6] The facility contained six 50-bed brick villas; official, administrative and laundry blocks; housing for staff;[2] and a hall with various workrooms that accommodated 320 people[7] (the functions of the hospital buildings and rooms would change over the years). Cunningham conducted the opening ceremony on 6 June 1913. Originally intended for the treatment of people with epilepsy, Stoneyetts was the first Poor Law epileptic colony in Scotland[2] and the only Scottish hospital ever built for epileptic individuals.[8] A remote location was chosen to shield patients from the general public.[7] Stoneyetts and local coal mining were important sources of employment for residents within the Moodiesburn area.[9]

Following the passing of the Mental Deficiency and Lunacy (Scotland) Act 1913, Stoneyetts became a facility for intellectually disabled people – then termed "mental defectives" – who had been held in asylums for the insane.[2] The hospital was known as "Stoneyetts Certified Institution for Mental Defectives" circa 1931.[10] As well as housing civilians, Stoneyetts received convicts who had been deemed mentally "defective"; Glasgow Govan MP Neil Maclean disapproved of "young lads, guilty merely of a little horse-play or a boyish escapade" being held at the institution.[11] The facility faced problems with overcrowding: arrangements were made with Falkirk Parish Council for patients to be cared for at Blinkbonny Home,[12] and the remaining residents were transferred to the new Lennox Castle Hospital by December 1936. Following restoration, Stoneyetts was re-opened as a unit for certified mental patients on 7 August 1937.[2][8]

The revised unit was headed by chief physician Dr Alexander Dick. Its first admissions were a number of Woodilee Hospital residents, owing to recent weather damage to that facility. Regular entertainment was provided for patients and staff: a cinema showing was supplied weekly, while the "Stoneyetts Concert Party" consisted of the kitchen staff and two female patients.[13] With the inception of the National Health Service (NHS) in 1948, Stoneyetts was linked with Woodilee and Gartloch hospitals under a single board of management. In 1954 there were 340 staffed beds.[2]

Improvements to the facility were carried out in 1950, at a cost of £6,800. These included an extension to the laundry, the addition of verandas to two of the villas and the erection of a designated patients' cafeteria.[2] A television set was installed in May 1953, courtesy of Sir John Stirling-Maxwell,[14] and a new oil-fired boiler was implemented in the late 1960s.[2] The institution was upgraded and modernised c. 1975.[8] A number of proposed improvements to the hospital were thwarted by the health board's inability to gain sufficient funding over the years.[2] In 1989, a £9,700 minibus was presented to Stoneyetts by the Parks and Recreation Charities Club.[15]

By the early 1970s there was a changing emphasis toward psychogeriatric care at Stoneyetts.[2] The institution became home to numerous Woodilee Hospital residents following the discovery of severe structural defects in the fabric of that facility's buildings on 13 March 1987 (dubbed "Black Friday" by Lenzie residents).[16] In 1988, patients at Stoneyetts ranged in age from 33 to 87, and included people with schizophrenia, new chronic sick individuals, long-term geriatric patients, and those being prepared for rehabilitation.[16] Three years later, residents were aged 40 to 98.[5] As of October 1991, the hospital had 180 beds and 260 staff members.[4]

Two local streets were laid that share the "Stoneyetts" name: Stoneyetts Road in Moodiesburn,[17] and Stoneyetts Drive within Woodilee Village, Lenzie.[18]

Closure

Stoneyetts was in serious need of funding by mid 1989; a fundraiser was organised at the Knights of St Columba social club in Moodiesburn.[19] In May 1991, however, NHS Greater Glasgow announced its plans to close institution,[20] with a view to transfer patients and staff to other locations.[21] Proponents for its closure described the facility's accommodation as "outdated"[4] and "sub-standard".[5]

Tom Clarke, MP for Monklands West, led the opposition against closure.[22] Hospital workers feared that Stoneyetts was being intentionally run down to justify its termination;[23] the Confederation of Health Service Employees (COHSE) had produced a catalogue of complaints against the institution in 1986, citing cockroach and mould infestation, dilapidated surroundings, and staff shortages.[24] Unions threatened to occupy the facility and organise a work-in if the plans went ahead.[25] Despite union opposition, as well as public outcry[4] and protesting by workers,[26] Scottish Health Minister, Michael Forsyth, announced his approval of the closure plans on 24 October 1991. COHSE official Jim Devine described Forsyth's ruling as "an affront to democracy", while Tom Clarke called it a "ruthless decision made on commercial not caring grounds".[4] Clarke demanded a probe into the hospital's closure.[27]

Operations at Stoneyetts officially ceased on 19 February 1992.[28]

Aftermath

NHS Greater Glasgow retained ownership of the land and allowed local players to continue funding the institution's bowling venue after the main buildings were demolished.[29] The brownfield hospital site became a popular location for dog walking,[29] but also for vandalism, fly tipping[30] and underage drinking.[29] Concerns were raised with regard to children playing in the area, particularly due to the presence of discarded hypodermic needles.[30]

The woodland was home to a large tree that became a popular spot for local youngsters during the 1990s. On 25 September 1999, an 11-year-old boy died after falling from the tree, prompting police to remove a home-made apparatus from it.[31][32]

In October 2001, the Stoneyetts area again became the cause of public unrest when the Scottish Prison Service expressed interest in purchasing the former hospital grounds to build a jail there.[6] Other proposed developments, including a shopping complex and a leisure centre, failed to materialise over the years.[29]

Several elements of the hospital site remained into the 2010s, such as a tree outline of the grounds, largely overgrown roads, unpowered street lighting, a disused football pitch, and building remnants including an accessible basement.[33] The nearby Stoneyetts Cottages still stand, despite being secluded from the site by the intersecting 2011 M80 motorway extension.[34]

In November 2016, the Stoneyetts land was put up for sale as a residential development site.[35] The following year Miller Homes announced 291 planned homes, while agreeing to retain Stoneyetts Bowling Club and much of the woodland; adjacent land by the entrance was procured by Persimmon for 60 proposed builds.[29] Persimmon gained clearance from North Lanarkshire Council in November 2018,[36] while Miller received permission in February 2019 and commenced work the following year.[37][38] In 2021, Taylor Wimpey announced they had received planning permission to build a further 121 homes on the site.[39]

References

- ↑ Higginbotham, Peter (2012). "Appendix H: Post-1845 Statutory Poorhouses in Scotland". The Workhouse Encyclopedia. The History Press. ISBN 978-0752470122.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 Dow, Derek A (August 1985). "NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Archives: Stoneyetts Hospital – History" (PDF). University of Glasgow. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- ↑ "North Lanarkshire: Vacant & Derelict Land 2013". North Lanarkshire Council. 7 August 2013. Archived from the original on 6 January 2015. Retrieved 22 November 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Hospital closure approved". Glasgow Herald. 25 October 1991. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Health Service (Greater Glasgow)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 25 July 1991. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Concerns over prison interest in Stoneyetts". Kirkintilloch Herald. 16 October 2001. Archived from the original on 3 October 2016. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 "Notes of the Month" (PDF). The Poor Law Magazine. Glasgow Caledonian University. 23 (7): 193 & 195. 1913. Archived from the original (PDF) on 5 October 2016. Retrieved 5 October 2016.

- 1 2 3 "Stoneyetts Hospital". Dictionary of Scottish Architects. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- ↑ "Moodiesburn". Gazetteer of Scotland. Retrieved 10 March 2021.

- ↑ "Stoneyetts Hospital, Glasgow". The National Archives. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ "Prisons Department For Scotland". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 25 February 1936. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ Tough, Alistair (23 July 1998). "NHS Greater Glasgow and Clyde Archives: Records". University of Glasgow. Archived from the original on 18 December 2004. Retrieved 23 June 2011.

- ↑ MacGregor, Alexander (1938). Report of the Medical Officer of Health (City of Glasgow): 1937. Corporation of Glasgow. p. 414; 436; 440.

- ↑ "TV for Hospitals". Glasgow Herald. 8 May 1953. p. 3. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "A key to easier transport for long-term patients". The Bulletin (89). October 1989. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- 1 2 "Stoneyetts and Woodilee Hospitals". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 29 January 1988. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ "Area Information for Stoneyetts Road, Moodiesburn". StreetCheck. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Convenience store site" (PDF). BusinessesForSale. Archived from the original (PDF) on 17 December 2016. Retrieved 17 December 2016.

- ↑ "Moodiesburn". Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser. 28 July 1989. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Gough, Jim (9 May 1991). "Hospital unions to fight move from closure". Evening Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Beattie, Gordon (26 December 1991). "Staff plan battle to save hospital". Evening Times: 13. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "MP steps up health fight". Glasgow Herald. 28 October 1991. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Montgomery, Fiona (25 September 1991). "Nurses hit out at staff levels". Evening Times: 11. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Smith, Ken (2 September 1986). "A creepy-crawlie hospital attack". Evening Times. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Simpson, Cameron (21 June 1991). "Hospital 'work-in' planned". Glasgow Herald. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ Rogers, Roy (25 September 1991). "NHS faces test on pay". Glasgow Herald: 5. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Hospital axe probe call". Evening Times. 28 October 1991. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Health Care (Strathclyde)". Parliamentary Debates (Hansard). 7 February 1995. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 "Miller to revamp Stoneyetts". Airdrie & Coatbridge Advertiser. 2 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Bowlers in safety plea". Kirkintilloch Herald. 6 July 2004. Archived from the original on 25 July 2011. Retrieved 24 August 2016.

- ↑ "Swing horror as boy dies in fall from tree". Sunday Mail. 26 September 1999. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ Smith, Ian (27 September 1999). "Boy, 11, dies after falling from tree". The Scotsman. The Scotsman Publications.

- ↑ "Moodiesburn: Stoneyetts Hospital grounds (2011)". The CWIB. 18 January 2015. Retrieved 12 January 2017.

- ↑ "M80 Noise Modelling Report" (PDF). Parsons Brinckerhoff. Transport Scotland. 1 December 2014. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 August 2016. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ↑ "Land for sale in Gartferry Road, Moodiesburn". Zoopla. Archived from the original on 17 November 2016. Retrieved 17 November 2016.

- ↑ "Construction of 60 dwellings and Associated Works, Roads and SUDS". North Lanarkshire Council. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ↑ McGrory, Neil (5 February 2019). "Houses on ex-hospital site get the go ahead". Cumbernauld News. Retrieved 6 February 2019.

- ↑ "Stoneyetts Village". Miller Homes. Archived from the original on 20 December 2020. Retrieved 20 December 2020.

- ↑ Brownlie, Lauren (3 July 2021). "Planning permission secured for 100 homes at former hospital site near Glasgow". Glasgow Times. Retrieved 21 September 2021.