Strato of Lampsacus | |

|---|---|

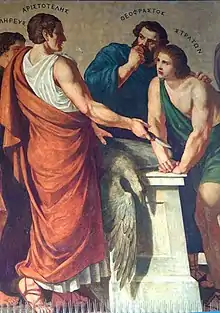

Strato, depicted as a medieval scholar in the Nuremberg Chronicle | |

| Born | c. 335 BCE |

| Died | c. 269 BCE (aged c. 66) |

| Era | Ancient philosophy |

| Region | Western philosophy |

| School | Peripateticism |

Main interests | Natural philosophy, Physics |

Strato of Lampsacus (/ˈstreɪtoʊ/; Greek: Στράτων ὁ Λαμψακηνός, translit. Strátōn ho Lampsakēnós, c. 335 – c. 269 BCE) was a Peripatetic philosopher, and the third director (scholarch) of the Lyceum after the death of Theophrastus. He devoted himself especially to the study of natural science, and increased the naturalistic elements in Aristotle's thought to such an extent, that he denied the need for an active god to construct the universe, preferring to place the government of the universe in the unconscious force of nature alone.

Life

Strato, son of Arcesilaus or Arcesius, was born at Lampsacus between 340 and 330 BCE.[1] He might have known Epicurus during his period of teaching in Lampsacus between 310 and 306 BCE.[1] He attended Aristotle's school in Athens, after which he went to Egypt as tutor to Ptolemy, where he also taught Aristarchus of Samos. He returned to Athens after the death of Theophrastus (c. 287 BCE), succeeding him as head of the Lyceum. He died sometime between 270 and 268 BCE.[1]

Strato devoted himself especially to the study of natural science, whence he obtained the name of Physicus (Greek: Φυσικός).[2] Cicero, while speaking highly of his talents, blames him for neglecting the most important part of philosophy, that which concerns virtue and morals, and giving himself up to the investigation of nature.[3] In the long list of his works, given by Diogenes Laërtius, several of the titles are upon subjects of moral philosophy, but the great majority belong to the department of physical science. None of his writings survive, his views are known only from the fragmentary reports preserved by later writers.

Philosophy

Strato emphasized the need for exact research,[4] and, as an example of this, he made use of the observation of how water pouring from a spout breaks into separate droplets as evidence that falling bodies accelerate.[5]

Whereas Aristotle defined time as the numbered aspect of motion,[6] Strato argued that because motion and time are continuous whereas number is discrete, time has an existence independent of motion,[7] or simply that time was the quantitative aspect of motion, rather than its numerical aspect. Simplicius preserves the following quotation in his commentary on Aristotle's Physics:

For we say we that we go abroad or sail or go on a military campaign or wage war for much time or for little time, and similarly, that we sit and sleep and do nothing for much time and for little time: for much time in the cases where the quantity is much, for little where it is little. For time is the quantitative in each of these. And this is why some people say that one and the same [thing] came slowly, others quickly, according to how the quantitative in this seems to each group. For we saw that that is quick in which the quantity from when it began to when it stopped is small, but much happened in this [interval]. Slow is the opposite, when the quantity in it is much, but what has been done is little. And for this reason, there is no quick and slow in rest, for all is equal to its own quantity, and neither much in a small quantity, or short in a large one. And this is why we speak of more and less time, but not of quicker or slower time. For an action and a motion can be quicker or slower, but the quantity in which the action is, is not quicker and slower, but more and less, like the time. Day and night, and month and year are not time or parts of time, but the former are light and dark, the latter the circuit of the moon and sun, while time is the quantity in which these are.[8]

He was critical of Aristotle's concept of place as a surrounding surface,[9] preferring to see it as the space which a thing occupies.[10] He also rejected the existence of Aristotle's fifth element.[11]

He emphasized the role of pneuma ('breath' or 'spirit') in the functioning of the soul; soul-activities were explained by pneuma extending throughout the body from the 'ruling part' located in the head.[12] All sensation is felt in the ruling-part of the soul, rather than in the extremities of the body; all sensation involves thought, and there is no thought not derived from sensation.[13] He denied that the soul was immortal, and attacked the 'proofs' put forward by Plato in his Phaedo.[4]

Strato believed all matter consisted of tiny particles, but he rejected Democritus' theory of empty space. In Strato's view, void does exist, but only in the empty spaces between imperfectly fitting particles; Space is always filled with some kind of matter.[14] Such a theory permitted phenomena such as compression, and allowed the penetration of light and heat through apparently solid bodies.[9]

He seems to have denied the existence of any god outside of the material universe, and to have held that every particle of matter has a plastic and seminal power, but without sensation or intelligence; and that life, sensation, and intellect, are but forms, accidents, and affections of matter. Cicero took exception to this:

Nor does his pupil Strato, who is called the natural philosopher, deserve to be listened to; he holds that all divine force is resident in nature, which contains, he says, the principles of birth, increase, and decay, but which lacks, as we could remind him, all sensation and form.[15]

Like the atomists (Leucippus and Democritus) before him, Strato of Lampsacus was a materialist and believed that everything in the universe was composed of matter and energy. Strato was one of the first philosophers to formulate a secular worldview, in which God is merely the unconscious force of nature.

You deny that without God there can be anything: but here you yourself seem to go contrary to Strato of Lampsacus, who concedes to God a pardon from a great task. If the priests of God were on vacation, it is much more just that the Gods would also be on vacation; in fact he denies the need to appreciate the work of the Gods in order to construct the world. All the things that exist he teaches have been produced by nature; not hence, as he says, according to that philosophy which claims these things are made of rough and smooth corpuscles, indented and hooked, the void interfering; these, he upholds, are dreams of Democritus which are not to be taught but dreamt. Strato, in fact, investigating the individual parts of the world, teaches that all that which is or is produced, is or has been produced, by weight and motion. Thus he liberates God from a big job and me from fear.[16]

Strato endeavoured to replace the Aristotelian teleology by a purely physical explanation of phenomena, the underlying elements of which he found in heat and cold, with especially heat as the active principle.[4] Although Strato's view of the universe can be seen as secular, he may have accepted the existence of gods within the universe, in the context of ancient Greek religion; it is unlikely that he would have regarded himself as an atheist.[17]

Geology

As quoted from Charles Lyell's Principles of Geology:

Strabo passes on to the hypothesis of Strato, the natural philosopher, who had observed that the quantity of mud brought down by rivers into the Euxine was so great, that its bed must be gradually raised, while the rivers still continued to pour in an undiminished quantity of water. He therefore conceived that, originally, when the Euxine was an inland sea, its level had by this means become so much elevated that it burst its barrier near Byzantium, and formed a communication with the Propontis, and this partial drainage had already, he supposed, converted the left side into marshy ground, and that, at last, the whole would be choked up with soil. So, it was argued, the Mediterranean had once opened a passage for itself by the Columns of Hercules into the Atlantic, and perhaps the abundance of sea-shells in Africa, near the Temple of Jupiter Ammon, might also be the deposit of some former inland sea, which had at length forced a passage and escaped.[18]

Also following the reference of Georgius Agricola Strato of Lampsacus, the successor of Theophrastus, wrote a book on the subject of metallic arts called De Machinis Metallicis.[19]

Modern influence

Strato's name meant little in the Middle Ages and the Renaissance. However, in the 17th century, his name suddenly became famous due to the supposed similarities between his system and the pantheistic views of Spinoza.[20] In his 1678 attack on atheism, Ralph Cudworth designated Strato's system as one of four types of atheism and in doing so, coined the term hylozoism to describe any system where primitive matter is endowed with a life force.[21] These ideas reached Pierre Bayle, who adopted Strato and 'Stratonism' as key components of his own philosophy.[22] In his Continuation des Pensées diverses, published in 1705, Stratonism became the most important ancient equivalent of Spinozism.[23] For Bayle, Strato had made everything to follow a fixed order of necessity, with no innate good or bad in the universe; the universe was not regarded as a living thing with intelligence or intent, and there is no other divine power but nature.[24] As the third head of the Peripatetic School in Greece, Strato also taught Aristarchus of Samos, who went on to present the first known heliocentric model as an alternative hypothesis to the then-acknowledged model of geocentrism.[25] The heliocentric model situated the Sun at the center of the universe, unlike geocentrism which placed the Earth at the center of the universe.[26] This Aristarchus had a significant impact on philosophers and scientists during the Hellenistic era of philosophy and science, and also later scholars, namely Copernicus and Kepler.

List of works

The list of his works is given by Diogenes Laërtius.[27]

- Of Kingship, three books.

- Of Justice, three books.

- Of the Good, three books.

- Of the Gods, three books.

- On First Principles, three books.

- On Various Modes of Life.

- Of Happiness.

- On the Philosopher-King.

- Of Courage.

- On the Void.

- On the Heaven.

- On the Wind.

- Of Human Nature.

- On the Breeding of Animals.

- Of Mixture.

- Of Sleep.

- Of Dreams.

- Of Vision.

- Of Sensation.

- Of Pleasure.

- On Colours.

- Of Diseases.

- Of the Crises in Diseases.

- On Faculties.

- On Mining Machinery.

- Of Starvation and Dizziness.

- On the Attributes Light and Heavy.

- Of Enthusiasm or Ecstasy.

- On Time.

- On Growth and Nutrition.

- On Animals the existence of which is questioned.

- On Animals in Folk-lore or Fable.

- Of Causes.

- Solutions of Difficulties.

- Introduction to Topics.

- Of Accident.

- Of Definition.

- On difference of Degree.

- Of Injustice.

- Of the logically Prior and Posterior.

- Of the Genus of the Prior.

- Of the Property or Essential Attribute.

- Of the Future.

- Examinations of Discoveries, in two books.

- Lecture-notes, Diogenes adds that its authorship is disputed.

- Letters beginning "Strato to Arsinoë greeting."

Notes

- 1 2 3 Dorandi 2005, p. 36

- ↑ Diogenes Laertius, Lives of the Philosophers, § 5.58

- ↑ Cicero, Acad. Quaest. i. 9; de Finibus, v. 5.

- 1 2 3 Zeller, Nestle & Palmer 2000, p. 204

- ↑ "This experiment goes back to a passage in Simplicius' Commentary on the Physics, where it is said that Strato of Lampsacus, had offered this "experiment" of pouring water from a spout as evidence of the fact that falling bodies are accelerated." Grant 1974, p. 227

- ↑ Aristotle, Physics, 4.11 219b5

- ↑ Furley 2003, p. 156

- ↑ Strato of Lampascus: Texts, Translation and Discussion; Routledge, 2011, Desclos and Fortenbaugh, eds. pg. 87

- 1 2 Furley 2005, p. 416

- ↑ Furley 2003, p. 157

- ↑ Furley 2005, p. 417

- ↑ Furley 2003, p. 162

- ↑ Furley 2003, p. 163

- ↑ Algra 1995, p. 58ff

- ↑ Cicero, De Natura Deorum, i. 13.

- ↑ Cicero, Lucullus, 121. quoted in Reale & Catan 1985, p. 103

- ↑ Israel 2006, p. 454

- ↑ Charles Lyell, Principles of Geology, 1832, p.20-21

- ↑ Georgius Agricola, De Re Metallica, from English traduction written by Herbert Clark Hoover and Lou Henry Hoover, p. xxvi

- ↑ Israel 2006, p. 445

- ↑ Erdmann 2002, p. 101

- ↑ Israel 2006, p. 447

- ↑ Israel 2006, p. 450

- ↑ Israel 2006, p. 451

- ↑ Centore, F. F. (1967-07-01). "Copernicus, Hooke and Simplicity". Philosophical Studies. 17: 185–196. doi:10.5840/philstudies196817093.

- ↑ Heath, Sir Thomas Little (2019-11-25). The Copernicus of Antiquity (Aristarchus of Samos). Good Press.

- ↑ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, v. 59, 60.

References

- Algra, Keimpe (1995), Concepts of Space in Greek Thought, Brill

- Dorandi, Tiziano (2005), "Chronology", in Algra, Keimpe; Barnes, Jonathon; Mansfeld, Jaap; Schofield, Malcolm (eds.), The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61670-0

- Erdmann, Johann Eduard (2002), A History of Philosophy, Anmol Publications

- Furley, David (2003), From Aristotle to Augustine : Routledge History of Philosophy, Volume 2, Routledge

- Furley, David (2005), "Cosmology", in Algra, Keimpe; Barnes, Jonathon; Mansfeld, Jaap; Schofield, Malcolm (eds.), The Cambridge History of Hellenistic Philosophy, Cambridge University Press, ISBN 0-521-61670-0

- Grant, Edward (1974), A Source Book in Medieval Science, Harvard University Press

- Israel, Jonathan Irvine (2006), Enlightenment Contested: Philosophy, Modernity, and the Emancipation of Man, Oxford University Press

- Reale, Giovanni; Catan, John R. (1985), A History of Ancient Philosophy, Vol 3, Suny Press

- Zeller, Eduard; Nestle, Wilhelm; Palmer, Leonard (2000), Outlines of the history of Greek philosophy, Routledge

Further reading

- Desclos, M. L.; Fortenbaugh, W., eds. (2012), Strato of Lampsacus: Text, Translation, Discussion, Transaction Publishers

, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, vol. 1:5, 1925

, Lives of the Eminent Philosophers, vol. 1:5, 1925