The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) is a three-bill package that passed the California state legislature and was signed into California state law by Governor Jerry Brown in September 2014. Its purpose is to ensure better local and regional management of groundwater use and it seeks to have a sustainable groundwater management in California by 2042. It emphasizes local management and formed groundwater sustainability agencies (GSAs) from local and regional authorities[1] who submitted groundwater sustainability plans (GSPs) to the state between 2020 and 2022.[2]

Background

Groundwater in California is used by 85% of California's population of 40 million and heavily used by the agriculture industry as the main water source for crops.[3] Prior to SGMA, groundwater use was under-regulated to a point where many areas of the state faced major depletion, particularly in the San Joaquin Valley and other groundwater basins on the central coast and southern California that have been designated by the State's Department of Water Resources (DWR) as being critically overdrafted.[4]

Groundwater is particularly crucial in California because the dearth of surface water in summer months in most of the state means that it supplies between one-third and two-thirds of the state's freshwater supply, depending on climatic conditions. It has been pumped in excess of the natural rate of replenishment, which in return is lowering the groundwater table, a phenomenon called "overdraft", that can cause severe land subsidence.[5]

In 1980, DWR noted that of California's 450 groundwater basins that were defined at the time, 40 were in overdraft and 11 were identified as being in "critically overdrafted conditions" (COD).[3] Groundwater levels had dropped from 50 feet below historic levels and up to 100 feet below in the San Joaquin Valley. In 2016, DWR identified an additional 10 basins as being in COD status for a total of 21 COD basins.[6] These COD basins are required to reach sustainability in a shorter timeframe, by 2040 rather than 2042 under SGMA.

Knowing how much groundwater is being taken out and used is difficult because there is no reporting requirement. Prior to SGMA there were only a few basins that reported to the state, operating under government regulation and special state legislation. SGMA mandates annual reporting of groundwater pumped in all high and medium priority basins.

Managing groundwater is also challenging because it does not adhere to property lines and often moves freely underground across jurisdictions. SGMA's requirement that GSAs are established and that GSAs and GSPs be coordinated across a basin or subbasin seeks to address this problem. Further, SGMA requires that neighboring basins consider each other's ability to achieve their sustainability goal.

Legislation

The Sustainable Groundwater Management Act (SGMA) consists of three bills. It was primarily authored by California State Assembly member Roger Dickinson (AB 1739) and State Senator Fran Pavley (SB 1319 and SB 1168).[1]

AB 1739

AB 1739 gives the California Department of Water Resources (DWR) or a groundwater sustainability agency (GSA) the authority to establish fees (detailed in SB 1168) and offer support to "entities that extract or use groundwater to promote water conservation and protect groundwater resources". GSAs are locally controlled organizations in California's high- and medium-priority groundwater basins and are responsible for preparing a groundwater sustainability plan (GSP), implementing SGMA, and coordinating with neighbors.[7]

AB 1739 also requires DWR to organize and publish an online report with estimates of groundwater replenishment and best practices. GSAs are required to submit a groundwater sustainability plan (GSP) to the DWR for review. DWR must determine regulations to evaluate, implement, and coordinate GSPs based on conditions of "hydrology, water demand, regulatory restrictions that affect the availability of surface water, and unreliability of, or reductions in, surface water deliveries to the agency or water users in the basin, and impact of those conditions on achieving sustainability and shall include the historic average reliability and deliveries of surface water to the agency or water users in the basin".[8]

SB 1319

Approved by Governor Jerry Brown on September 16, 2014, Senator Pavley's SB 1319 authorized local agencies to implement a groundwater plan. Management of groundwater prior to the Sustainable Groundwater Management Act was unregulated and voluntary for the various agencies using groundwater ranging from special districts under authority granted from the state, city, and county ordinances and court adjudicated basins. Senate bill 1319 requires for the groundwater management plans to follow specific and include components that the state deems as sustainable for the specific groundwater basin and aligns with the SGMA timeline. If an agency was seeking funds from the Department of Water Resources for a project regarding groundwater or groundwater quality, they too have to abide to specific requirements such as preparing and implementing a groundwater management plan.[9] Managing groundwater is a challenging task, one that has been addressed by the SGMA. Groundwater is out of sight which makes it difficult to monitor, especially when the groundwater basins boundaries reach across multiple agencies and users. Pumping unregulated and mismanaged groundwater can lead to a "tragedy of the commons", with each user maximizing the resource for their own gain with little responsibility for the depleting aquifer. The SGMA initially set basin boundaries based on a 2003 Department of Water Resources report, Bulletin 118-03.[10] The report delineated 431 groundwater basins statewide. Of these basins, 24 were subdivided into 108 subbasins to total 515 basins and subbasins in all. The report based these boundaries off the alluvial sediments found using various geologic maps.[11] Groundwater is difficult to manage as it is not neatly aligned with the jurisdiction of these set basin boundaries. The SGMA calls for the GSAs to communicate and work with the overlapping groundwater uses and allow for a governance of the basin through different means. These can include a memorandum of agreement between the multiple parties or through a legal joint agreement. By these agreements the groundwater basin can be regulated by multiple GSAs or just by one agency.

SB 1168

The California Constitution and SB 1168 require that any use of the groundwater be both reasonable and beneficial.[12] California has a history of complex water rights, in which the Reasonable and Beneficial Use Doctrine is a key tenet. The doctrine was originally developed for riparian landowners and surface water management, but SB 1168 applied it to the context of groundwater and the SGMA, stating that any use of groundwater has to be sustainably managed for long-term reliability and multiple economic, social, and environmental benefits for future uses.[12]

Specifically, SB 1168 gives GSAs the authority to:

- Require registration from a groundwater extraction facility

- Require that a groundwater extraction facility be measured by a water-measuring device and to regulate the extraction based on the measurements

- Conduct inspections and obtain warrants

It requires the Department of Water Resources to:

- Investigate California's groundwater basins every five years and report its findings to the California State Legislature

- Look at the monitoring of groundwater elevations in each basin and prioritize them based on adverse effects to the local habitats and streamflows

.jpg.webp)

SB 13 amendments

Since the collection of bills that make up SGMA were complex, some minor changes were made in SB 13 pertaining to GSA formation. Prior to SB 13, existing law required that each high- and medium-priority groundwater basins be managed after implementing a groundwater sustainability plan and subjected reporting requirements to the State Water Resources Control Board. SB 13 changed DWR's role with respect to reviewing, posting, and tracking GSA formation notices. Changes include notifying reviews, GSA boundaries which overlap, and service area boundaries.[13]

Bill overview

Key definitions

Key terms in the SGMA are defined as follows:[14]

- Sustainable yield: the maximum quantity of water calculated over long-term conditions in the basin, including any temporary excess that can be withdrawn over a year without an undesirable result

- Sustainable groundwater management: the management and use of groundwater that can be maintained without causing an undesirable result.

- Undesirable results include any of the following:

- Persistent lowering of groundwater levels

- Significant and unreasonable reductions in groundwater storage

- Significant and unreasonable saltwater intrusion

- Significant and unreasonable degradation of water quality

- Significant and unreasonable land subsidence

- Surface water depletion having significant and unreasonable effects on beneficial uses

Groundwater sustainability agencies

A GSA is a local agency that implements the SGMA as the primary entity responsible for reaching groundwater sustainability.[15] It is required to develop and implement a groundwater sustainability plan (GSP) to consider the interests of all of its stakeholders.

Any local agency or combinations thereof may form a GSA for the basin in which they overlap. A "local agency" refers to a local public agency that has water supply, management, and land use obligations within the groundwater basin. The SGMA determined 43 high-priority groundwater basins and 84 medium-priority groundwater basins, totaling 127 basins accounting for 96% of California's groundwater. These basins must adopt GSPs by 2020 or 2022 (depending on the basin) and have until 2040 or 2042 to attain sustainability. A local agency can decide not to form a GSA and submit an alternative proposal to DWR if they believe the alternative will meet the objectives and long-term goals of the SGMA. The DWR is required to assess the alternative proposal to see if it satisfies the objectives and goals of the SGMA. If it does not, the local agency is required to form a GSA and develop a GSP.[16] The SGMA required GSAs to be formed by June 30, 2017.

Implementation deadlines

| When | Who | What |

|---|---|---|

| January 31, 2015 | Department of Water Resources (DWR) | Categorize and prioritize basins as high, medium, low, or very low. |

| January 1, 2016 | DWR | Adopt regulations for basin boundary adjustments and accept adjustment requests from local agencies. |

| April 1, 2016 | Local water agencies or watermasters in adjudicated areas | Submit final judgment /order / decree and required report to DWR (report annually thereafter). |

| June 1, 2016 | DWR | Adopt regulations for evaluating adequacy of Groundwater Sustainability Plans (GSPs) and Groundwater Sustainability Agency (GSA) coordination agreements |

| December 31, 2016 | DWR | Publish report estimating water available for groundwater replenishment |

| January 1, 2017 | DWR | Publish groundwater sustainability best management practices |

| By June 30, 2017 | Local agencies | Establish GSAs |

| After July 1, 2017 | State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) | Designate basins as probationary where GSAs have not been formed |

| After July 1, 2017 | Groundwater users in probationary basins | Adopt GSPs and begin managing basins under GSPs |

| January 31, 2020 | GSAs in other medium- and high- priority basins | File annual groundwater extraction report with SWRCB by December 15 each year |

| After January 31, 2022 | SWRCB | Designate basins as probationary where GSPs have not been adopted in other medium- and high-priority basins |

| After January 31, 2025 | SWRCB | Designate basins as probationary where GSPs are inadequate or not being implemented, and extractions result in significant depletions of interconnected surface waters |

| After January 31, 2040 | GSAs (in medium- and high-priority basins in critical overdraft) | Achieve groundwater sustainability goals (DWR may grant two five-year extensions upon a showing of good cause) |

| After January 31, 2042 | GSAs (in other medium- and high-priority basins) | Achieve groundwater sustainability goals (DWR may grant two five-year extensions upon a showing of good cause)[17] |

As part of its implementation, DWR has developed a Strategic Plan to document its Sustainable Groundwater Management (SGM) Program, which expands on its responsibilities in SGMA. The Strategic Plan describes the state's groundwater conditions, identifies legislation, policies, and success factors, describes the goals and objectives of DWR actions, and presents the plan for DWR communication and outreach with stakeholders.[18]

Reception

Support

Support for the act stemmed from the goal of avoiding negative impacts of lowering the water table and subsidence throughout California with implementing specific, measurable objectives. California has had a long history of complex water rights dealing with the ownership and management of surface water. Groundwater has stayed under the regulation radar, which led to the overdraft of vital basins and the subsidence of land taking place throughout the Central Valley. The SGMA gives responsibility to both state authority and local oversight to bring groundwater basins in California to sustainable yields within a given time period.

Opposition

One of the main arguments in opposition of AB 1739 and SB 1168 was from the California Farm Bureau Federation (CFBF), which was concerned that the bills were rushed and did not allow enough time to address many of the complex issues of groundwater. In addition, the Farm Bureau explained that there would be "huge long-term economic impacts" on farms as well as state and local economies, with a "very real potential to devalue land", thereby affecting the viability of farms and business as well as jobs.[19] Opponents from the CFBF included counties in the Central Valley and agricultural businesses.[20]

Implementation

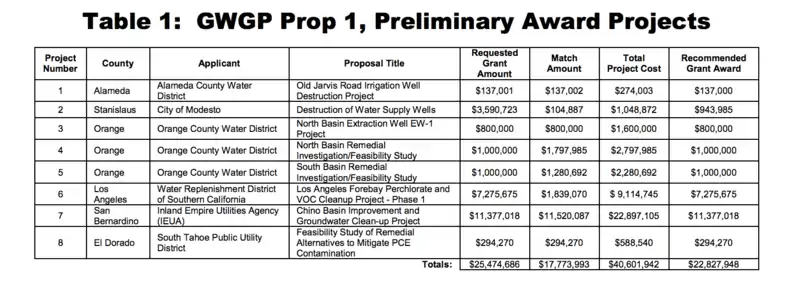

The approval of Proposition 1, the Water Quality, Supply, and Infrastructure Improvement Act, guaranteed $900 million in funding for the development of a Groundwater Sustainability Program.[21] The State Water Resources Control Board (SWRCB) administers $800 million,[22] and the DWR will administer the remaining $100 million as Sustainable Groundwater Planning Grant Funds for developing programs that support the SGMA.[23] The DWR has released the first draft of the Proposal Solicitation Package (PSP) for GSPs. This initial PSP has made $86.3 million available for the, "planning, development, or preparation of GSPs" and a minimum of $10 million from the initial PSP has been earmarked for Severely Disadvantaged Communities.[8] Eligibility for grant approval requires that the GSPs address high- or medium-priority basins. The SWRCB has already released its initial round of funding for certain preventive and restorative groundwater initiatives which can be seen below.

Full implementation of the groundwater sustainability act could force 750,000 acres (300,000 ha) of farmland out of production according to the Public Policy Institute of California.[25]

See also

References

- 1 2 "Groundwater: Sustainable Groundwater Management Act". Division of Agriculture and Natural Resources. University of California, Davis. Retrieved 8 February 2018.

- ↑ "SGMA Portal".

- 1 2 "Understanding California's Groundwater | Water in the West". Stanford University. Retrieved 2016-04-01.

- ↑ "Department of Water Resources Critically Overdrafted Basins Website".

- ↑ Tara Moran (April 2015). Amanda Cravens (ed.). California's Sustainable Groundwater Management Act of 2014: Recommendations for Preventing and Resolving Groundwater Conflicts (PDF). Stanford, CA: Water in the West, Stanford University.

- ↑ "Bulletin 118 - Interim Update 2016" (PDF).

- ↑ "Sustainable Groundwater Management Act" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- 1 2 "Proposal Solicitation Package For Groundwater Sustainability Plans and Projects" (PDF).

- ↑ "Bill Text - SB-1319 Groundwater". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-25.

- ↑ "California's Groundwater, Update 2003".

- ↑ "The 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: A Handbook to Understanding and Implementing the Law" (PDF). watereducation.org. Water Education Foundation. 2015. Retrieved May 7, 2016.

- 1 2 "Bill Text - SB-1168 Groundwater management". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-05-07.

- ↑ CA Department of Water Resources. "Groundwater Sustainability Agencies". water.ca.gov. State of California. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ University of California, Davis (2015). The 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: A Handbook to Understanding and Implementing the Law (PDF). Sacramento, CA: Water Education Foundation. pp. 1–90. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ Kincaid, Valerie; Stager, Ryan (September 2015). Know Your Options: A Guide to Forming Groundwater Sustainability Agencies (PDF). California Water Foundation. pp. 1–44. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ University of California, Davis (2015). The 2014 Sustainable Groundwater Management Act: A Handbook to Understanding and Implementing the Law (PDF). Sacramento, CA: Water Education Foundation. pp. 1–90. Retrieved 8 May 2016.

- ↑ Resources, University of California, Division of Agriculture and Natural. "Sustainable Groundwater Management Act". groundwater.ucdavis.edu. Retrieved 2016-04-03.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ "Groundwater Sustainability Program". water.ca.gov. California Department of Water Resources. March 9, 2015.

{{cite web}}: Missing or empty|url=(help) - ↑ "Bill Analysis". leginfo.legislature.ca.gov. Retrieved 2016-04-04.

- ↑ Cannon Leahy, Tina (January 2016). "Desperate Times Call for Sensible Measures: The Making of the California Sustainable Groundwater Management Act". Golden Gate University Environmental Law Journal. 9 (4): 34.

- ↑ Draft Proposal Solicitation Package for Groundwater Sustainability Plans and Projects. "Draft Proposal Solicitation Package for Groundwater Sustainability Plans and Projects". Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ "State Water Board Approves Proposition 1 Funding for Cleanup of Groundwater Contamination" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ "Sustainable Groundwater Management Act" (PDF). Retrieved 6 August 2017.

- ↑ "State Water Board Approves Proposition 1 Funding for Cleanup of Groundwater Contamination" (PDF). 6 August 2017. Retrieved 7 August 2017.

- ↑ Walters, Dan (November 30, 2021). "Column: Drought has big impacts on California agriculture". Ventura County Star. Retrieved 2021-12-01.