Tamil culture is the culture of the Tamil people. Tamil culture is rooted in the arts and ways of life of Tamils in India, Sri Lanka, Malaysia, Singapore, and across the globe. It has a long history of diversified heritage and cultural distinctions.

Language and literature

Tamils have a strong attachment to the Tamil language, which is often venerated in literature as "Tamil̲an̲n̲ai", "the Tamil mother".[2] It has historically been, and to large extent still is, central to the Tamil identity.[3] Like the other languages of South India, it is unrelated to the Indo-European languages of northern India. The Tamil language preserves many features of Proto-Dravidian, though modern-day spoken Tamil in Tamil Nadu freely uses loanwords from Sanskrit and English and vice versa. Also, the language does not have many commonly used alphabets in English language and Hindi (a product of Sanskrit and written in Devanagri script).[4] Tamil literature is of considerable antiquity, and is recognised as a classical language by the government of India. Classical Tamil literature, which ranges from lyric poetry to works on poetics and ethical philosophy, is remarkably different from contemporary and later literature in other Indian languages, and represents the oldest body of secular literature in South-east Asia.[5]

Religion

Tamil religious texts

_(13903661293).jpg.webp)

The ancient Tamil grammatical work of the Tolkappiyam and the Sangam works of the Ten Idylls (Pattuppāṭṭu) and the Eight Anthologies (Eṭṭuttokai) shed light on early religion of ancient Dravidian people. Thirumal is indicated to be the deity associated with the mullai tiṇai (pastoral landscape) in the Tolkappiyam.[6][7] He is regarded to be the only deity who enjoyed the status of Paramporul (achieving oneness with Paramatma) during the Sangam age. He is also known as Māyavan, Māmiyon, Netiyōn, and Māl in Sangam literature.[8] A reference to "Mukkol Pakavars" in Sangam literature indicates that only Vaishnava saints were holding Tridanda and were prominent during the period. Tirumal was glorified as "the supreme deity", whose divine lotus feet could burn all evil and grant moksha. During the post-Sangam period, his worship was further glorified by the poet-saints called the Alvars.[9][10]

Murugan was glorified as, the god of war, who is ever young and resplendent, as the favoured god of the Tamils.[11] Sivan was also seen as the supreme God.[11] Early iconography of Murugan[12] and Shiva[13] and their association with native flora and fauna goes back to Indus Valley Civilization.[14][15] The Sangam landscape was classified into five categories, thinais, based on the mood, the season and the land. Tolkappiyam, mentions that each of these thinai had an associated deity such as Thirumal in Mullai-the forests, Murugan in kurinji -the Hills and Venthan in Marutham-the plains,Kotravai in Palai-the desert and Wanji-ko/kadalon in the Neithal-the coasts and the seas. Other gods mentioned were Mayyon who were all assimilated into Hinduism over time.

The Ramavataram or Kamba Ramayanam of Kamban is an epic of about 11,000 stanzas.[16][17] The Rama-avataram or Rama-kathai as it was originally called was accepted into the holy precincts in the presence of Vaishnava Acharya Naathamuni.[18]Kamba Ramayana is not a verbal translation of the Sanskrit epic by Valmiki, but a retelling of the story of Rama.[18]

The Ramavataram or Kamba Ramayanam of Kamban is an epic of about 11,000 stanzas.[16][17] The Rama-avataram or Rama-kathai as it was originally called was accepted into the holy precincts in the presence of Vaishnava Acharya Naathamuni.[18]

Demographics

About 88%[19] of the population of Tamil Nadu are Hindus. Christians and Muslims account for 6% and 5.5% respectively.[19] The majority of Muslims in Tamil Nadu speak Tamil,[20] with less than 15% of them reporting Urdu as their mother tongue.[21] Tamil Jains number only a few thousand now.[22] Atheist, rationalist, and humanist philosophies are also adhered by sizeable minorities, as a result of Tamil cultural revivalism in the 20th century, and its antipathy to what it saw as Brahminical Hinduism.[23]

Tamil Jains constitute around 0.13% of the population of Tamil Nadu.[19] Many of the rich Tamil literature works were written by Jains.[24] According to George L. Hart, the legend of the Tamil Sangams or "literary assemblies" was based on the Jain sangham at Madurai.[25]

Deities and veneration

The most popular deity is Murugan, he is known as the patron god of the Tamils and is also called "Tamil Kadavul" (Tamil God).[26][27] In Tamil tradition, Murugan is the youngest son and Ganesha/Pillayar is the eldest son of Shiva/Sivan, and it is different from the North Indian tradition, which represents Murugan as the eldest son. The goddess Parvati is often depicted as a goddess with a green skin complexion in Tamil Hindu tradition. The worship of Amman, also called Mariamman, is thought to have been derived from an ancient mother goddess, and is also very common.[28] Kan̲n̲agi, the heroine of the Cilappatikār̲am, is worshipped as Pattin̲i by many Tamils, particularly in Sri Lanka.[29] There are also many followers of Ayyavazhi in Tamil Nadu, mainly in the southern districts.[30] In addition, there are many temples and devotees of Vishnu, Siva, Ganapathi, and the other Hindu deities. Muslims across Tamil Nadu follow Hanafi and Shafi'i schools. Erwadi in Ramanathapuram district and Nagore in Nagapattinam district[31] are the major pilgrimage centres for Muslims in Tamil Nadu.

In rural Tamil Nadu, many local deities, called aiyyan̲ārs, are thought to be the spirits of local heroes who protect the village from harm.[32] Their worship often centres around nadukkal, stones erected in memory of heroes who died in battle. This form of worship is mentioned frequently in classical literature and appears to be the surviving remnants of an ancient Tamil tradition.[33]

The Saivist sect of Hinduism is significantly represented amongst Tamils, more so among Sri Lankan Tamils, although most of the Saivist places of religious significance are in northern India. The Alvars and Nayanars, who were predominantly Tamils, played a key role in the renaissance of Bhakti tradition in India. In the 10th century, the philosopher Ramanuja, who propagated the theory of Visishtadvaitam, brought many changes to worshipping practices, creating new regulations on temple worship, and accepted lower-caste Hindus as his prime disciples.[34]

Festivals

The most important Tamil festivals are Pongal, a harvest festival that occurs in mid-January, and Puthandu, the Tamil New Year, which occurs on 14 April. Both are celebrated by almost all Tamils, regardless of religion. The Hindu festival Deepavali is celebrated with fanfare; other local Hindu festivals include Thaipusam, Panguni Uttiram, and Adiperukku. While Adiperukku is celebrated with more pomp in the Cauvery region than in others, the Ayyavazhi Festival, Ayya Vaikunda Avataram, is predominantly celebrated in the southern districts of Kanyakumari District, Tirunelveli, and Thoothukudi.[35]

Tamil traditions

Various martial arts including Adimurai, Kuttu Varisai, Varma Kalai, Silambam, Adithada, Malyutham and Kalarippayattu, are practised in Tamil Nadu and Kerala.[36] The warm-up phase includes yoga, meditation and breathing exercises. Silambam originated in ancient Tamilakam and was patronized by the Pandyans, Cholas and Cheras, who ruled over this region. Silapathigaram, a Tamil literature from the 2nd century CE, refers to the sale of Silamabam instructions, weapons and equipment to foreign traders.[37] Since the early Sangam age, there was a warlike culture in South India. War was regarded as an honourable sacrifice and fallen heroes and kings were worshipped in the form of a Hero stone. Each warrior was trained in martial arts, and horse riding and specialized in two of the weapons of that period Vel (spear) Val (sword) and Vil (bow).[38] Heroic martyrdom was glorified in ancient Tamil literature. The Tamil kings and warriors followed an honour code similar to that of Japanese Samurais and committed suicide to save their honor. The forms of martial suicide were known as Avipalli, Thannai, Verttal, Marakkanchi, Vatakkiruttal and Punkilithu Mudiyum Maram. Avipalli was mentioned in all the works except Veera Soliyam. It was a self-sacrifice of a warrior to the goddess of war for the victory of his commander. The Tamil rebels in Sri Lanka reflected some elements of Tamil martial traditions which included worship of fallen heroes (Maaveerar Naal) and practice of martial suicide. They carried a Suicide pill around their neck to escape the captivity and torture.[39] A remarkable feature besides to their willingness to sacrifice is, that they were well-organized and disciplined. It was forbidden for the rebels to consume tobaccos, alcohols, drugs and to have sexual relationships.[40]

The Wootz steel originated in South India and Sri Lanka.[41][42] There are several ancient Tamil, Greek, Chinese and Roman literary references to high-carbon Indian steel since the time of Alexander's India campaign. The crucible steel production process started in the sixth century BCE, at production sites of Kodumanal in Tamil Nadu, Golconda in Andhra Pradesh, Karnataka and Sri Lanka and exported globally; the Tamils of the Chera Dynasty producing what was termed the finest steel in the world, i.e. Seric Iron to the Romans, Egyptians, Chinese and Arabs by 500 BCE.[43][44][45] The steel was exported as cakes of steely iron that came to be known as "Wootz."[46]

The Tamilakam method was to heat black magnetite ore in the presence of carbon in a sealed clay crucible inside a charcoal furnace. An alternative was to smelt the ore first to give wrought iron, then heated and hammer to be rid of slag. The carbon source was bamboo and leaves from plants such as Avārai.[46][47] The Chinese and locals in Sri Lanka adopted the production methods of creating Wootz steel from the Chera Tamils by the 5th century BCE.[48][49] In Sri Lanka, this early steel-making method employed a unique wind furnace, driven by the monsoon winds, capable of producing high-carbon steel and production sites from antiquity have emerged, in places such as Anuradhapura, Tissamaharama and Samanalawewa, as well as imported artefacts of ancient iron and steel from Kodumanal. A 200 BCE Tamil trade guild in Tissamaharama, in the South East of Sri Lanka, brought with them some of the oldest iron and steel artefacts and production processes to the island from the classical period.[50][51][52][53] The Arabs introduced the South Indian/Sri Lankan wootz steel to Damascus, where an industry developed for making weapons of this steel. The 12th-century Arab traveller Edrisi mentioned the "Hinduwani" or Indian steel as the best in the world.[54][41] Another sign of its reputation is seen in a Persian phrase – to give an "Indian answer", meaning "a cut with an Indian sword."[49] Wootz steel was widely exported and traded throughout ancient Europe and the Arab world, and became particularly famous in the Middle East.[49]

Traditional Weapons

Tamil martial arts also include various types of weapons.

- Valari (throwing iron sickle)

- Maduvu (deer horns)

- Surul Vaal (curling blade)

- Vaal (sword) + Ketayam (shield)

- Itti or Vel (spear)

- Savuku (whip)

- Kattari (fist blade)

- Veecharuval (battle Machete)

- Silambam (long bamboo staff)

- Kuttu Katai (spiked knuckleduster)

- Katti (dagger/knife)

- Vil (bow)

- Tantayutam (mace)

- Soolam (trident)

- Theekutchi (flaming baton)

- Yeratthai Mulangkol (dual stick)

- Yeretthai Vaal (dual sword)

Visual art and architecture

Most traditional arts are religious in some form and usually, centres on Hinduism, although the religious element is often only a means to represent universal—and, occasionally, humanist—themes.[56]

The most important form of Tamil painting is Tanjore painting, which originated in Thanjavur in the 9th century. The painting's base is made of cloth and coated with zinc oxide, over which the image is painted using dyes; it is then decorated with semi-precious stones, as well as silver or gold thread.[57] A style which is related in origin, but which exhibits significant differences in execution, is used for painting murals on temple walls; the most notable example are the murals on the Ranganathaswamy Temple, Srirangam and the Brihadeeswarar temple of Tanjore.[58]

Tamil sculpture ranges from elegant stone sculptures in temples, to bronze icons with exquisite details.[59] The medieval Chola bronzes are considered to be one of India's greatest contributions to the world art.,[60][61] Unlike most Western art, the material in Tamil sculpture does not influence the form taken by the sculpture; instead, the artist imposes his/her vision of the form on the material.[62] As a result, one often sees in stone sculptures flowing forms that are usually reserved for metal.[63]

Music

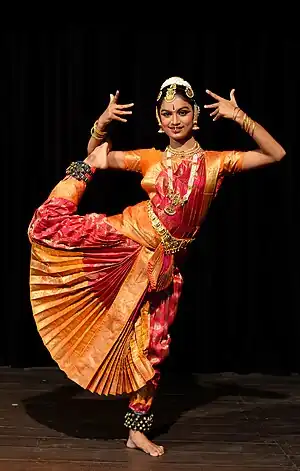

Tamil country has its own music form called Tamil Pannisai, from which current Carnatic music evolved. Has its own music troops like Urumi melam, Pandi melam (present day's chenda melam), Mangala Vathiyam, and Kailaya vathiyam etc.,. Ancient Tamil works, such as the Silappatikaram, describe a system of music,[64] and a 7th-century Pallava inscription at Kudimiyamalai contains one of the earliest surviving examples of Indian music in notation.[65] Contemporary dance forms such as Bharatanatyam have recent origins but are based older temple dance forms known as Sadirattam as practised by courtesans and a class of women known as Devadasis[66]

Performing arts

Famous Tamil dance styles are

- Bharatanatyam (Tamil classical dance)

- Sadirattam (Tamil classical dance- erotic music and movements similar to mohiniattam)

- Karakattam (Tamil ancient folk dance)

- Koothu (A folk and street dance)

- Kaliyal (A folk dance using sticks and intricate movements)

- Devarattam (A dance of warriors)

- Kai-silambam (A folk dance holding silambam in hand)

- Paraiattam (A folk drums and dance)

- Kavadiattam (dedicated to the Tamil God Murugan)

- Kummiyattam (female folk dance)

- Bommalattam (Puppet dance)

- Puliyattam (Tiger dance)

- Mayilattam (Peacock dance)

- Paampu attam (snake dance)

- Oyilattam (Dance of Grace)

- Poikkaal Kuthirai Aattam (False legged horses dance)

Contemporary dance forms such as Bharatanatyam have recent origins but are based on older temple dance forms known as Catir Kacceri as practised by courtesans and a class of women known as Devadasis[66] One of the Tamil folk dances is karakattam. In its religious form, the dance is performed in front of an image of the goddess Mariamma.[67] The kuravanci is a type of dance-drama, performed by four to eight women. The drama is opened by a woman playing the part of a female soothsayer of the kurava tribe(people of hills and mountains), who tells the story of a lady pining for her lover. The therukoothu, literally meaning "street play", is a form of village theatre or folk opera. It is traditionally performed in village squares, with no sets and very simple props.[68] The performances involve songs and dances, and the stories can be either religious or secular.[69] The performances are not formal, and performers often interact with the audience, mocking them, or involving them in the dialogue. Therukkūthu has, in recent times, been very successfully adapted to convey social messages, such as abstinence and anti-caste criticism, as well as information about legal rights, and has spread to other parts of India.[70] Tamil Nadu also has a well-developed stage theatre tradition, which has been influenced by western theatre. A number of theatrical companies exist, with repertoires including absurdist, realist, and humorous plays.[71]

Film and theatre arts

The theatrical culture flourished in Tamil culture during the classical age. Tamil theatre has a long and varied history whose origins can be traced back almost two millennia to dance-theatre forms like Kotukotti and Pandarangam, which are mentioned in an ancient anthology of poems entitled the Kalingathu Parani.[72]

The predominant theatre form of the region is Kattaikkuttu, where performers (historically men) sing, act, dance and are accompanied by musicians on traditional instruments. The majority of performances draw from stories in the Mahabharata, while a few plays take their inspiration from Purana stories.

The modern Tamil film industry originated during the 20th century. The Tamil film industry has its headquarters in Chennai and is known under the name Kollywood, it is the second largest film industry in India after Bollywood.[73] Films from Kollywood entertain audiences not only in India but also overseas Tamil diaspora. Tamil films from Chennai have been distributed to various overseas cinemas in Singapore, Sri Lanka, South Africa, Malaysia, Japan, Oceania, the Middle East, Western Europe, and North America.[74] Inspired by Kollywood originated outside India Independent Tamil film production in Sri Lanka, Singapore, Canada, and western Europe. Several Tamil actresses such as Anuisa Ranjan Vyjayanthimala, Hema Malini, Rekha Ganesan, Sridevi, Meenakshi Sheshadri, and Vidya Balan have acted in Bollywood and dominated the cinema over the years. Historical chief ministers of Tamil Nadu, including M. G. Ramachandran, M. Karunanidhi and J. Jayalalithaa, were previously successful personalities in the Tamil film industry.

Jallikattu

In Ancient times, two bullfighting and bull-racing sports were conducted. 1.Manjuvirattu and 2. Yeruthazhuval. These sports were organised to keep the people's temperament always fit and ready for war at any time. Each has its own techniques and rules. These sports acted as one of the criteria to marry girls of warrior families. There were traditions where the winner would be chosen as a bridegroom for their daughter or sister.

Gandhirajan, a post-graduate in Art History from Madurai-Kamaraj University, said the ancient Tamil tradition was "manju virattu" (chasing bulls) or "eruthu kattuthal" (lassoing bulls) and it was never "jallikattu," that is baiting a bull or controlling it as the custom obtained today. In ancient Tamil country, during the harvest festival, decorated bulls would be let loose on the "peru vazhi" (highway) and the village youth would take pride in chasing them and outrunning them. Women, elders and children would watch the fun from the sidelines of the "peru vazhi" or streets. Nobody was injured in this. Or the village youth would take delight in lassoing the sprinting bulls with "vadam" (rope). It was about 500 years ago, after the advent of the Nayak rule in Tamil Nadu with its Telugu rulers and chieftains, that this harmless bull-chasing sport metamorphosed into "jallikattu," according to Gandhirajan.[75]

The ancient Tamil art of unarmed bullfighting, popular amongst warriors in the classical period,[76][77] has also survived in parts of Tamil Nadu, notably Alanganallur near Madurai, where it is known as Jallikattu and is held once a year around the time of the Pongal festival.

See also

Notes

References

- ↑ Tamil Virtual University

- ↑ See Sumathi Ramasamy, Passions of the Tongue, 'Feminising language: Tamil as Goddess, Mother, Maiden' Chapter 3.

- ↑ (Ramaswamy 1998)

- ↑ Kailasapathy, K. (1979), "The Tamil Purist Movement: A Re-Evaluation", Social Scientist, 7 (10): 23–51, doi:10.2307/3516775, JSTOR 3516775

- ↑ See Hart, The Poems of Ancient Tamil: Their Milieu and their Sanskrit Counterpart (1975)

- ↑ Hardy, Friedhelm (1 January 2015). Viraha Bhakti: The Early History of Krsna Devotion. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 156. ISBN 978-81-208-3816-1.

- ↑ Clothey, Fred W. (20 May 2019). The Many Faces of Murukan: The History and Meaning of a South Indian God. With the Poem Prayers to Lord Murukan. Walter de Gruyter GmbH & Co KG. p. 34. ISBN 978-3-11-080410-2.

- ↑ Padmaja, T. (2002). Temples of Kr̥ṣṇa in South India: History, Art, and Traditions in Tamilnāḍu. Abhinav Publications. p. 27. ISBN 978-81-7017-398-4.

- ↑ Ramesh, M. S. (1997). 108 Vaishnavite Divya Desams. T.T. Devasthanams. p. 152.

- ↑ Singh, Nagendra Kr; Mishra, A. P. (2005). Encyclopaedia of Oriental Philosophy and Religion: A Continuing Series--. Global Vision Publishing House. p. 34. ISBN 978-81-8220-072-2.

- 1 2 Kanchan Sinha, Kartikeya in Indian art and literature, Delhi: Sundeep Prakashan (1979).

- ↑ Mahadevan, Iravatham (2006). A Note on the Muruku Sign of the Indus Script in light of the Mayiladuthurai Stone Axe Discovery. harappa.com. Archived from the original on 4 September 2006.

- ↑ Steven Rosen, Graham M. Schweig (2006). Essential Hinduism. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 45.

- ↑ Basham 1967

- ↑ Frederick J. Simoons (1998). Plants of life, plants of death. p. 363.

- 1 2 Legend of Ram By Sanujit Ghose

- 1 2 Gopal, Madan (1990). K.S. Gautam (ed.). India through the ages. Publication Division, Ministry of Information and Broadcasting, Government of India. p. 212.

- 1 2 3 Rays and Ways of Indian Culture By D. P. Dubey

- 1 2 3 "Census 2001 – Statewise population by Religion". Censusindia.gov.in. Retrieved 18 July 2010.

- ↑ More, J.B.P. (2007), Muslim identity, print culture and the Dravidian factor in Tamil Nadu, Hyderabad: Orient Longman, ISBN 978-81-250-2632-7 at p. xv

- ↑ Jain, Dhanesh (2003), "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan languages", in Cardona, George; Jain, Dhanesh (eds.), The Indo-Aryan Languages, Routledge language family series, London: Routledge, pp. 46–66, ISBN 0-7007-1130-9 at p. 57.

- ↑ Total number of Jains in Tamil Nadu was 88,000 in 2001. Directorate of Census Operations – Tamil Nadu, Census, archived from the original on 30 November 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ Maloney, Clarence (1975), "Religious Beliefs and Social Hierarchy in Tamiḻ Nāḍu, India", American Ethnologist, 2 (1): 169–191, doi:10.1525/ae.1975.2.1.02a00100 at p. 178

- ↑ Jaina Literature in Tamil, Prof. A. Chakravartis

- ↑ "There was a permanent Jaina assembly called a Sangha established about 604 A.D. in Madurai. It seems likely that this assembly was the model upon which tradition fabricated the sangam legend." "The Milieu of the Ancient Tamil Poems, Prof. George Hart". 9 July 1997. Archived from the original on 9 July 1997. Retrieved 21 April 2012.

- ↑ M. Shanmugam Pillai, "Murukan in Cankam Literature: Veriyattu Tribal Worship", First International Conference Seminar on Skanda-Murukan in Chennai, 28–30 December 1998. This article first appeared in the September 1999 issue of The Journal of the Institute of Asian Studies, retrieved 6 December 2006

- ↑ Harold G. Coward, John R. Hinnells, Raymond Brady Williams, The South Asian Religious Diaspora in Britain, Canada, and the United States

- ↑ "Principles and Practice of Hindu Religion", Hindu Heritage Study Program, archived from the original on 14 November 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ PK Balachandran, "Tracing the Sri Lanka-Kerala link", Hindustan Times, 23 March 2006, archived from the original on 10 December 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ Dr. R.Ponnus, Sri Vaikunda Swamigal and the Struggle for Social Equality in South India, (Madurai Kamaraj University) Ram Publishers, Page 98

- ↑ Indian Dargah's All Cities

- ↑ Mark Jarzombek (2009), "Horse Shrines in Tamil India: Reflections on Modernity" (PDF), Future Anterior, 4 (1): 18–36, doi:10.1353/fta.0.0031

- ↑ "'Hero stone' unearthed", The Hindu, Chennai, India, 22 July 2006, archived from the original on 1 October 2007, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ "Redefining secularism", The Hindu, Chennai, India, 18 March 2004, archived from the original on 27 May 2004, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ Information on declaration of holiday on the event of birth anniversary of Vaikundar in The Hindu[usurped], The holiday for three Districts: Daily Thanthi, Daily(Tamil), Nagercoil Edition, 5 March 2006

- ↑ Zarrilli, Phillip B. (1992) "To Heal and/or To Harm: The Vital Spots in Two South Indian Martial Traditions"

- ↑ IN INDIA

- ↑ South Asian Folklore: An Encyclopedia : Afghanistan, Bangladesh, India, Nepal, Pakistan, Sri Lanka(2003), p. 386.

- ↑ Sri Lankan Ethnic Crisis: Towards a Resolution (2002), p. 76.

- ↑ Encyclopedia of Modern Worldwide Extremists and Extremist Groups, p.252.

- 1 2 Sharada Srinivasan; Srinivasa Ranganathan (2004). India's Legendary Wootz Steel: An Advanced Material of the Ancient World. National Institute of Advanced Studies. OCLC 82439861.

- ↑ Gerald W. R. Ward. The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. pp.380

- ↑ Sharada Srinivasan (1994). Wootz crucible steel: a newly discovered production site in South India. Papers from the Institute of Archaeology 5(1994) 49-59

- ↑ Herbert Henery Coghlan. (1977). Notes on prehistoric and early iron in the Old World. pp 99-100

- ↑ B. Sasisekharan (1999).TECHNOLOGY OF IRON AND STEEL IN KODUMANAL- Archived 2016-02-01 at the Wayback Machine

- 1 2 Hilda Ellis Davidson. The Sword in Anglo-Saxon England: Its Archaeology and Literature. pp.20

- ↑ Burton, Sir Richard Francis (1884). The Book of the Sword. Internet archive: Chatto and Windus. p. 111. ISBN 1605204366.

- ↑ Needham, Volume 4, Part 1, p. 282.

- 1 2 3 Manning, Charlotte Speir. Ancient and Medieval India. Volume 2. ISBN 9780543929433.

- ↑ Hobbies - Volume 68, Issue 5 - Page 45. Lghtner Publishing Company (1963)

- ↑ Mahathevan, Iravatham (24 June 2010). "An epigraphic perspective on the antiquity of Tamil". The Hindu. Archived from the original on 1 July 2010. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ Ragupathy, P (28 June 2010). "Tissamaharama potsherd evidences ordinary early Tamils among population". Tamilnet. Tamilnet. Retrieved 31 October 2010.

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 3 September 2013. Retrieved 24 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link) - ↑ S. Srinivasan and S. Ranganathan, "WOOTZ STEEL: AN ADVANCED MATERIAL OF THE ANCIENT WORLD", Department of Metallurgy, Indian Institute of Science, Bangalore

- ↑ "Krishna Rajamannar with His Wives, Rukmini and Satyabhama, and His Mount, Garuda | LACMA Collections". collections.lacma.org. Archived from the original on 16 July 2014. Retrieved 23 September 2014.

- ↑ Coomaraswamy, A.K., Figures of Speech or Figures of Thought

- ↑ "Tanjore – Painting", tanjore.net, Tanjore.net, retrieved 4 December 2006

- ↑ Nayanthara, S. (2006), The World of Indian murals and paintings, Chillbreeze, ISBN 81-904055-1-9 at pp.55–57

- ↑ "Shilpaic literature of the tamils", V. Ganapathi, INTAMM, retrieved 4 December 2006

- ↑ Aschwin Lippe (December 1971), "Divine Images in Stone and Bronze: South India, Chola Dynasty (c. 850–1280)", Metropolitan Museum Journal, The Metropolitan Museum of Art, 4: 29–79, doi:10.2307/1512615, JSTOR 1512615, S2CID 192943206,

The bronze icons of the Early Chola period are one of India's greatest contributions to world art...

- ↑ Heaven sent: Michael Wood explores the art of the Chola dynasty, Royal Academy, UK, archived from the original on 3 March 2007, retrieved 26 April 2007

- ↑ Berkson, Carmel (2000), "II The Life of Form pp29–65", The Life of Form in Indian Sculpture, Abhinav Publications, ISBN 81-7017-376-0

- ↑ Sivaram 1994

- ↑ Nijenhuis, Emmie te (1974), Indian Music: History and Structure, Leiden: Brill, ISBN 90-04-03978-3 at pp. 4–5

- ↑ Widdess, D. R. (1979), "The Kudumiyamalai inscription: a source of early Indian music in notation", in Picken, Laurence (ed.), Musica Asiatica, vol. 2, London: Oxford University Press, pp. 115–150

- 1 2 Leslie, Julia. Roles and rituals for Hindu women, pp.149–152

- ↑ Sharma, Manorama (2004). Folk India: A Comprehensive Study of Indian Folk Music and Culture, Vol. 11

- ↑ "Therukoothu". Tamilnadu.com. 16 February 2013. Archived from the original on 19 June 2013.

- ↑ Tamil Art History, eelavar.com, archived from the original on 27 April 2006, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ "Striving hard to revive and refine ethnic dance form", The Hindu, Chennai, India, 11 November 2006, archived from the original on 1 October 2007, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ "Bhagavata mela", The Hindu, Chennai, India, 30 April 2004, archived from the original on 13 November 2004, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ Dennis Kennedy The Oxford Encyclopedia of Theatre and Performance, Publisher:Oxford University Press

- ↑ Templeton, Tom (26 November 2006), "The states they're in", Guardian, 26 November 2006, London: guardian.com, retrieved 5 December 2006

- ↑ "Eros buys Tamil film distributor", Business Standard, 6 October 2011

- ↑ T.S. Subramanian (2008), "The Hindu epaper The Bull fight tradition existed 2,000 years ago and more...", The Hindu, archived from the original on 17 January 2008, retrieved 15 January 2008

- ↑ Gau (2001), Google books version of the book A Western Journalist on India: The Ferengi's Columns by François Gautier, ISBN 978-81-241-0795-9, retrieved 24 May 2007

- ↑ Grushkin, Daniel (22 March 2007), "NY Times: The ritual dates back as far as 2,000 years...", The New York Times, retrieved 24 May 2007

Sources

- Basham, Arthur Llewellyn (1967). The Wonder That was India.

- Hiltebeitel, Alf (2007). "Hinduism". In Kitagawa, Joseph (ed.). The Religious Traditions of Asia: Religion, History, and Culture. Routledge. pp. 3–40. ISBN 9781136875977.

- Krishnamurti, Bhadriraju (2003). The Dravidian Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-77111-0.

- Larson, Gerald (1995). India's Agony Over Religion. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-0-7914-2411-7.

- Lockard, Craig A. (2007). Societies, Networks, and Transitions. Volume I: to 1500. Cengage Learning. ISBN 978-0618386123.

- Tiwari, Shiv Kumar (2002). Tribal Roots of Hinduism. New Delhi: Sarup & Sons. ISBN 9788176252997.

- Zimmer, Heinrich (1951). Philosophies of India. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-20279-2.