תל קירי (Hebrew) | |

Shown within Israel | |

| Location | HaZore'a, Israel |

|---|---|

| Region | Border between the Menashe Heights and Jezreel Valley |

| Coordinates | 32°38′38″N 35°06′53″E / 32.64389°N 35.11472°E |

| Type | Ancient village, cemetery |

| Area | 10 dunams (1 hectare; 2.5 acres) |

| History | |

| Periods | Neolithic, Chalcolithic, Bronze Age, Iron Age, Persian, Hellenistic, Roman, Early Arab, Ottoman |

| Satellite of | Tel Yokneam |

| Site notes | |

| Archaeologists | Amnon Ben-Tor, Miriam Avissar |

| Completely covered by HaZore'a's houses today. | |

Tel Qiri (Hebrew: תל קירי) is a tel and an ancient village site located inside the modern kibbutz of HaZore'a in northern Israel. It lies on the eastern slopes of the Menashe Heights and the western edge of the Jezreel Valley. As of the beginning of the excavations in 1975, almost half of the site was still visible, but today the entire site is covered by the houses of HaZore'a. The site spans an area of one hectare and is believed to have been a dependency of the nearby Tel Yokneam. The site hosted some human activity during the Neolithic and Chalcolithic periods, as well as parts of the Bronze Age. An uninterrupted sequence of settlement lasted from the Iron Age to the Roman-Byzantine period. Unlike all urban centers in northern Israel, the village in Tel Qiri, which flourished during the Iron Age, escaped all military events and no traces of destruction can be found there. This minor, damaged and seemingly insignificant site yielded an amazingly rich and diverse quantity of remains of different periods.[1][2][3]

The excavation of Tel Qiri is part of the Yoqneam Regional Project, which conducted excavations at nearby Tel Yokneam and Tel Qashish.[3]

Geography

Tel Qiri is located on the slopes of Menashe Heights, on the connecting point between the heights and the Jezreel Valley. It does not have the typical shape of a mound, but is more like a terrace, sloping steeply towards the nearby Shofet River.[2] It is situated on the route between the two major ancient cities of Yokneam and Megiddo, which are located on major junctions of the international Via Maris route. The climate is moderate, water is abundant, and the soil is fertile, making it an excellent place for an agricultural settlement. The site is located within the boundaries of Kibbutz HaZore'a. The activity of the kibbutz, as well as the digging of defensive positions during the 1948 war, have severely damaged the site.[4]

Archaeology

The excavations in Tel Qiri took place between 1975 and 1977. A total of three seasons of six weeks each were conducted. The excavation was a rescue excavation, as the site was destined to be destroyed by the further expansion of the nearby settlement. The excavation was partially funded by the Israel Antiquities Authority and was a joint project of the authority along with the Institute of Archaeology of the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and the Israel Exploration Society. It was headed by Amnon Ben-Tor and Yuval Portugali.[5]

Archaeologists have unearthed eleven strata of settlement. The deepest, eleventh layer contains remains of an agricultural settlement from the Neolithic period (c. 10,000 – 4500 BCE) and potsherds from the Ghassulian culture (c. 4400 – 3500 BCE) and first half of the Early Bronze Age (c. 3000 – 2200 BCE). The village was re-established during the Middle Bronze Age, c. 1750 – 1650 BCE, and ceased to exist in the Late Bronze Age (c. 1550 – 1200 BCE). An era of uninterrupted settlement begins at the start of the Iron Age (c. 1200 – 539 BCE) and continues through the Achaemenid (539–330 BCE), Hellenistic (330–63 BCE), and up until the Roman Empire and Byzantine periods (63 BCE – 634 CE).[1]

Bronze Age

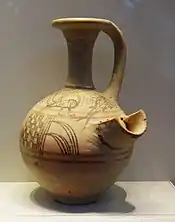

The Middle Bronze Age remains include some walls and pottery. It most likely existed during the latter part of the Middle Bronze Age, from 2000 to 1550 BCE. It seems the settlement was limited to the eastern part of the site and did not have any fortification system.[6] Only fragmentary remains from the Late Bronze Age were found and these do not include any remains of buildings or walls. One explanation may be that upon constructing the succeeding Iron Age settlement, the Late Bronze Age settlement was completely leveled and its stones were looted, but this is a bit far-fetched. It seems that the Late Bronze Age settlement, had there been one, was much more limited than the preceding Iron Age settlement. Out of the handful of remains are two Mycenaean and Cypriot ceramics, as well as other luxury and high-quality ceramics. This phenomenon has no clear explanation, but it may be that these all were imported to the site. This group of ceramics is specifically dated to the beginning of the Late Bronze Age (1550–1300 BCE), but can also represent the entire period (up until 1200 BCE).[7]

Iron Age period

Tel Qiri was settled throughout the entire Iron Age period. The excavation has revealed five settlement strata, further divided into twelve phases.[8] Most of the remains from the later days of the Iron Age were partially or completely lost due to modern residential construction. Several oil mills from this period were found. The farmers grew bitter vetch, wheat, pistachios, olives, and pomegranate. Most of the bones found were of sheep and goats; a minority of the bones belong to cows and other wild animals such as gazelle, deer, wild pig, and bear.[9]

The earliest Iron Age layer is dated to the beginning of the Iron Age I period, around the 12th century BCE. Remains of a large building, with a system of rooms and an oven, are noteworthy. A Canaanite jar was discovered, which seems to have been carried over from the previous Late Bronze Age. The absence of Philistine pottery is also noteworthy and implies this layer represent a time before the Philistines settled the region.[10]

A system of houses and agricultural installations was found dated to the Iron Age I period, between the 12th to 10th centuries BCE. Some of the pottery belongs to Philistine types. One of the houses, dated to the 11th century BCE yielded several tools used in religious rituals. An Egyptian amulet made of faience in the form of the Egyptian deity of Ptah-Sokar, typical of this period, was found, as well as an incense burner. An interesting discovery from a later stage of the building was an abundance of animal bones. Most of the bones belonged to sheep and goats, and most of them were the right forelegs of the animals. Such a collection of bones is unique to this building and indicates animal sacrifices, similar to a type of sacrifice described in the Hebrew Bible (Exodus 29:22 and Leviticus 7:32). This type of Israelite sacrifice was common in the Near East during this period and originated in this region. An example of this sacrifice method is found in a Late Bronze Age temple at Tel Lachish. Although this temple looks like a regular house, it is common to find religious activity in regular houses during this period and mentions of rituals done inside regular houses can be found in the Hebrew Bible in Judges 17:5. Another prevalent finding in Tel Qiri's Iron Age layers is the large quantity of chalices, which constitute a much higher percentage of Tel Qiri's ceramics than in other sites. It is possible that Tel Qiri had more temples and was a religious center in the region, or that it was connected to the extensive religious activity of the nearby Mount Carmel.[11][12]

At the beginning of the Iron Age II period, around the 9th century BCE, the supposed time of the United Kingdom of Israel and later the Samarian Kingdom of Israel, an entire residential section of the village was replaced by an oil production industry. Some of the structures were leveled off for these new installations. Pottery found from that period included very large cooking pots, some marked with unknown, letter-like marks.[13]

A large public building, 12 m (39 ft) wide and 16.5 m (54 ft) long, with massive walls between 1–1.4 m (3 ft 3 in – 4 ft 7 in) wide, was found from this era. The building first had a large courtyard room and two small rooms. In a later period, new walls were built inside to create two small and two large rooms. Some of the ceramics have been proven to be imported thanks to a study of their clay composition. The ceramics are dated to the 8th-century BCE.[14]

In 720 BCE the northern Kingdom of Israel was conquered by the Neo-Assyrian Empire along with Tel Qiri and the rest of the north. By looking at the architectural remains it seems the settlement underwent some changes in its plan. An Assyrian-style bottle was discovered close to the surface, next to a modern road. In 586 BCE the Assyrian rulers were replaced by the Neo-Babylonian Empire and a pilgrim-flask of this period was found. A flower pot was discovered, and parallels of this vessel were later found at the nearby Tel Yokneam and Tell Keisan. These vessels are foreign to the Jezreel Valley and seem to have been imported from the coastal region and are probably of Phoenician origin; and Tel Keisan is a possible option.[15]

Philistine presence

The Philistines were an ancient nation mentioned numerous times in the Hebrew Bible for their wars and conflicts against the Israelites. Philistine-type pottery was found in almost every site in the Jezreel Valley dating from the early 12th century through the late 11th century, corresponding to the time of the Biblical judges who, according to the Bible, ruled over the Israelites during the time of their settlement in Canaan. Vessels with Philistine decorations and pottery with collared-rims were often found nearby, leading archeologists to relate them to the Philistines as well.[16]

In the Iron Age I settlement, dated to the said period, some Philistine pottery was found. Items included a decorated jug and collared-rim sherds. Scholars have attributed the appearance of Philistine pottery in northern Israel to their role as Egyptian mercenaries during the time Egypt ruled over the Levant, and either an indication of their expansion north or their trade with Israelite and Canaanite cities. Several mentions of the presence of Philistines in the north are found in the Book of Judges.[16]

Persian cemetery

The actual settlement during the Persian period was not discovered, but pottery scattered all over the site indicates that the site was inhabited throughout the entire Persian period (539–330 BCE). The excavation did find a Persian cemetery with some 18 tombs dated between 450 and 300 BCE. One distinct feature of these burials is that they lack any grave goods. This may indicate a certain burial custom of the ethnic group that lived there, or otherwise their poverty.[17] The number of people buried in each grave varies from one to three. In the latter case there are usually a male, a female, and a child, and around a third of them are younger than 17, while only one skeleton belonged to a person older than 50. An extensive study of the skeletons was made by Baruch Arensburg of the Tel Aviv University. The female individuals buried in the graveyard appear to have been considerably shorter than the men, with an average height of 152 cm (4.99 ft) and 171 cm (5.61 ft), respectively. The difference in the height between the sexes (19 cm (7.5 in)) is greater than the modern average difference (12 cm (4.7 in)). This was hypothesized to be because of social conditions discriminating against women, possibly in terms of food consumption.[18]

The features of the skulls resemble people from Iron Age sites in Iran rather than to Iron Age Mediterranean people. One theory suggests that these are Jews who were expelled during the Babylonian captivity and returned by the royal decree of the Persian emperor Cyrus the Great. Changes in morphology due to migration only were recorded in the past. Another theory suggests that these people were Jews who had intermarried before they returned to their homeland. The most plausible explanation for the Iranian-looking skulls is simply that these people originated in a non-Mediterranean region and most probably from Iran. They may have been the families of ex-soldiers or mercenaries.[18]

Later periods

Out of the poor remains of the Hellenistic period, it can be understood that the site housed human activity throughout the entire Hellenistic period (330–63 BCE), most of it between 250 BCE and 150 BCE.[19] Four coins from this period were found. Three coins attributed to Ptolemy II Philadelphus, ruler of the Ptolemaic Kingdom were found. The first is a silver coin, bearing the face of Ptolemy himself, struck at the year 252 BCE in Acre. The second coin is a bronze coin, bearing the face of Zeus, struck between 246 and 271 BCE in Tyre. The third is essentially like the second but much smaller and its date unknown. Another coin is a much later bronze coin struck on 112–111 BCE. During this time Tel Qiri was under the rule of either the Seleucid Empire or the Hasmonean dynasty.[20]

The remains from Roman times were quite poor. Not a single plan of a building could be reconstructed. The finds from the Early Roman period included many cooking pots and storage jars. The Early Roman settlement is dated from 63 BCE – immediately after the Romans conquered the region – to 25 CE. The latest settlement layer yields poor remains, including potsherds, which overlap in their date at between 300 and 350 CE, which is the proposed date of this layer. These can be dated as early as 230 CE and as late as 450 CE and even later.[19]

Sixteen Muslim burials were discovered, dug into the latest settlement layers from Roman and Hellenistic times. The faces of the deceased faced south, towards Mecca. Three of the burials yield remains such as beads and a stone pendant, which helps determine that most of the burials are from the 18th to 19th centuries CE, when the country was under Ottoman rule. Otherwise, one of the burials may be dated to the 13th century CE.[21] A bronze coin from the Umayyad period was found, with the inscription "By the name of Allah this fils was struck at Tiberias".[20]

See also

References

- 1 2 A. Ben-Tor, M. Avisar, Ruhama Bonfíl, I. Zerzetsky and Y. Portugali, A Regional Study of Tel Yoqneʿam and Its Vicinity, Qadmoniot 77–79, 1987 p. 3 (Hebrew)

- 1 2 Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p.1–4

- 1 2 Ben-Tor, 1979, p.105

- ↑ Ben-Tor, 1979, pp.106–107

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p.XIX

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p. 272

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp. 257–8

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p.53

- ↑ Ben-Tor, Portugali, 1987, p.137

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp. 99–101

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp 86–98

- ↑ Nakhai, Beth Alpert (2001). Archaeology and the Religions of Canaan and Israel. Vol. ASOR Books Volume 7. Boston: American Schools of Oriental Research. p. 174. ISBN 0-89757-057-X.

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp. 67–74

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p.105

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p. 62–66

- 1 2 Avner Raban, "The Philistines in the Western Jezreel Valley". Bulletin of the American Schools of Oriental Research. The University of Chicago Press on behalf of The American Schools of Oriental Research. 284: 17, 20, 23–25. November 1991.

- ↑ Ben-Tor, Portugali, 1987, pp.15-26

- 1 2 Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp. 27–28, 31–33

- 1 2 Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp. 9-15

- 1 2 Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, p. 51

- ↑ Ben-Tor and Portugali, 1987, pp.7-8

Bibliography

- Amnon Ben-Tor, Tell Qiri: A look at Village Life, The Biblical Archaeologist 42, vol. 2, 1979, pp. 105–113

- Amnon Ben-Tor and Yuval Portugali, Tell Qiri: A Village in the Jezreel Valley: Report of the Archaeological Excavations 1975–1977, Qedem, 1987, pp. 1–299