Textile manufacturing is one of the oldest human activities. The oldest known textiles date back to about 5000 B.C. In order to make textiles, the first requirement is a source of fibre from which a yarn can be made, primarily by spinning. The yarn is processed by knitting or weaving to create cloth. The machine used for weaving is the loom. Cloth is finished by what are described as wet process to become fabric. The fabric may be dyed, printed or decorated by embroidering with coloured yarns.

The three main types of fibres are natural vegetable fibres, animal protein fibres and artificial fibres. Natural vegetable fibres include cotton, linen, jute and hemp. Animal protein fibres include wool and silk. Man-made fibres (made by industrial processes) including nylon, polyester will be used in some hobbies and handicrafts and in the developed world.

Almost all commercial textiles are produced by industrial methods. Textiles are still produced by pre-industrial processes in village communities in Asia, Africa and South America. Creating textiles using traditional manual techniques is an artisan craft practised as a hobby in Europe and North America.[1] Traditional practices are also kept alive by artisans in China and Japan, for instance at the Chinese Printed Blue Nankeen Exhibition Hall (Blue Cloth Museum) in Shanghai.[2]

Yarn formation

Vegetable fibres

Flax

The preparations for spinning is similar across most plant fibres, including flax and hemp. Flax is the fibre used to create linen. Cotton is handled differently since it uses the fruit of the plant and not the stem.

Harvesting

Flax is pulled out of the ground about a month after the initial blooming when the lower part of the plant begins to turn yellow, and when the most forward of the seeds are found in a soft state. It is pulled in handfuls and several handfuls are tied together with slip knot into a 'beet'. The string is tightened as the stalks dry. The seed heads are removed and the seeds collected, by threshing and winnowing.

Retting

Retting is the process of rotting away the inner stalk, leaving the outer fibres intact. A standing pool of warm water is needed, into which the beets are submerged. An acid is produced when retting, and it would corrode a metal container.

At 80 °F (27 °C), the retting process takes 4 or 5 days, it takes longer when colder. When the retting is complete the bundles feel soft and slimy. The process can be overdone, and the fibres rot too.

Dressing the flax

Dressing is removing the fibres from the straw and cleaning it enough to be spun. The flax is broken, scutched and hackled in this step.

- Breaking The process of breaking breaks up the straw into short segments. The beets are untied and fed between the beater of the breaking machine, the set of wooden blades that mesh together when the upper jaw is lowered.

- Scutching In order to remove some of the straw from the fibre a wooden scutching knife is scaped down the fibres while they hang vertically.

- Heckling Fibre is pulled through various sized heckling combs. A Heckling comb is a bed of sharp, long-tapered, tempered, polished steel pins driven into wooden blocks at regular spacing. A good progression is from 4 pins per square inch, to 12, to 25 to 48 to 80. The first three will remove the straw, and the last two will split and polish the fibres. Some of the finer stuff that comes off in the last heckles can be carded like wool and spun. It will produce a coarser yarn than the fibres pulled through the heckles because it will still contain some straw.

Spinning

Flax can either be spun from a distaff, or from the spinner's lap. Spinners keep their fingers wet when spinning, to prevent forming fuzzy thread. Usually singles are spun with an "S" twist. After flax is spun it is washed in a pot of boiling water for a couple of hours to set the twist and reduce fuzziness.

Many handspinners will buy a roving of flax. This roving is spun in the same manner as above. The rovings may come with very long fibres (4 to 8 inches), or much shorter fibres (2 to 3 inches).

Cotton

Cotton is a soft, fluffy staple fibre that grows in a boll, or protective capsule, around the seeds of cotton plants of the genus Gossypium. The fibre is almost pure cellulose.

The plant is a shrub native to tropical and subtropical regions around the world, including the Americas, Africa, and India. The greatest diversity of wild cotton species is found in Mexico, followed by Australia and Africa.[3] Cotton was independently domesticated in the Old and New Worlds. The most favoured cottons are the ones with the longest staple as they can be spun into the finest thread. Sea Island and Egyptian are two of these. Surat an Indian species has a short staple. Hand operated methods of processing remained the preferred way of spinning and weaving the very finest threads and fabrics into the third quarter of the nineteenth century.

Yucca

Yucca fibres were at one time widely used throughout Central America for many things. Currently they are mainly used to make twine.Yucca leaves are harvested and then cut to a standard size. The leaves are crushed in between two large rollers producing the fibres which are bundled up and dried in the sun over trellises. The dried fibres are combined into rolags. At this point it is ready to spin. The waste, a pulpy liquid that stinks, can be used as a fertilizer.

Animal protein fibres

Wool

Wool is a protein based fibre, being the coat of a sheep. The wool is removed by shearing.

Sheep Shearing

Shearing can be done with use of hand-shears or powered shears. Professional sheep shearers can shear a sheep in under a minute, without nicking the sheep.

The fleece is removed in one piece. Second cuts can be made but produce only short fibres, which are more difficult to spin. Primitive breeds, like the Scottish Soay sheep have to be plucked, not sheared, as the kemps are still longer than the soft fleece, (a process called rooing).

Skirting

Skirting is disposing of all wool that is unsuitable for spinning. Recovering can be attempted. It can also be done at the same time as carding.

Cleaning

The wool is cleaned. At this point the fleece is full of lanolin and often contains extraneous vegetable matter, such as sticks, twigs, burrs and straw. These may all be removed, though lanolin may be left in the wool till after the spinning, a technique known as spinning 'in the grease'. Indeed, if the fabric is to be water repellent, lanolin is not removed at any stage.

Washing the wool at this stage can be a tedious process. Some people wash it a small handful at a time very carefully, and then set it out to dry on a table in the sun. Others will wash the whole fleece. Lanolin is removed by soaking the fleece in very hot water. If the fleece gets agitated, it will become felt, and then spinning is impossible. Felting, when done on purpose (with needles, chemicals, or simply rubbing the fibres against each other), can be used to create garments.

Carding or combing

It is possible to spin directly from a clean fleece, but it is much easier to spin a carded fleece. Carding by hand yields a rolag, a loose woollen roll of fibres. Using a drum carder yields a bat, which is a mat of fibres in a flat, rectangular shape. Carding mills return the fleece in a roving, which is a stretched bat; it is very long and often the thickness of a wrist. A pencil roving is a roving thinned to the width of a pencil. It can be used for knitting without any spinning, or for apprentices.

Combing is another method to align the fibres parallel to the yarn, and thus is good for spinning a worsted yarn, whereas the rolag from handcards produces a woolen yarn.

Spinning

Hand spinning can be done by using a spindle or the spinning wheel. Spinning turns the carded wool fibres into yarn which can then be directly woven, knitted (flat or circular), crocheted, or by other means turned into fabric or a garment.

The spinning wheel collects the yarn on a bobbin. A woollen yarn is lightly spun so it is airy, and is a good insulator and suitable for knitting, while a worsted yarn is spun tight to exclude air, and has greater strength and is suited to weaving..

Once the bobbin is full, the hobby spinner either puts on a new bobbin, or forms a skein, or balls the yarn. A skein is a coil of yarn twisted into a loose knot. Yarn is skeined using a niddy noddy or other type of skein -winder. Yarn is rarely balled directly after spinning, it will be stored in skein form, and transferred to a ball only if needed. Knitting from a skein, is difficult as the yarn forms knots, in this case it is best to ball. Yarn to be plied is left on the bobbin.

A skein is either formed by the hobby spinner, on a niddy noddy or some other type of skein winder. Traditionally niddy-noddys looked like an uppercase "i", with the bottom half rotated 90 degrees. Hobby spinning wheel manufactures also make niddy-noddys that attach onto the spinning wheel for faster skein winding.

Plying

Plying yarn is when one takes a strand of spun yarn (one strand is often called a single) and spins it together with other strands in order to make a thicker yarn.

Regular plying consists of taking two or more singles and twisting them together, the against their twist. This can be done on a spinning wheel or on a spindle. If the yarn was spun clockwise (which is called a "Z" twist ), to ply, the wheel must spin counter-clockwise (an "S" twist). This is the most common way. When plying from bobbins a device called a lazy kate is often used to hold them.

Most hobby spinners (who use spinning wheels) ply from bobbins. This is easier than plying from balls because there is less chance for the yarn to become tangled and knotted if it is simply unwound from the bobbins. So that the bobbins can unwind freely, they are put in a device called a lazy kate, or sometimes simply kate. The simplest lazy kate consists of wooden bars with a metal rod running between them. Most hold between three and four bobbins. The bobbin sits on the metal rod. Other lazy kates are built with devices that create an adjustable amount of tension, so that if the yarn is jerked, a whole bunch of yarn is not wound off, then wound up again in the opposite direction. Some spinning wheels come with a built in lazy kate.

Navajo plying consists of making large loops, similar to crocheting. A loop about 8-inch (20 cm) long is made on the leader the end on the leader (a leader is the string left on the bobbin to spin off.) The three strands together are spun in the opposite direction. When a third of the loop remains, a new loop is created and the spinning continues. The process is repeated until the yarn is all plied. The advantage of this method is that only one single is needed and if the single is already dyed this technique allows it to be plied without ruining the color scheme. This technique also allows the spinner to try to match up thick and thin spots in the yarn, thus making for a smoother end product.

Washing

If the lanolin is unwanted, and has not already been washed out, this is done now. The skein is tied in six points and steeped overnight in detergent, it is rinsed and air-dried, and re-skeined.

Unless the lanolin is to be left in the cloth as a water repellent. When washing a skein it works well to let the wool soak in soapy water overnight, and rinse the soap out in the morning. Dishwashing detergents are commonly used, and a special laundry detergent designed for washing wool is not required. The dishwashing detergent works and does not harm the wool. After washing, let the wool dry (air drying works best). Once it is dry, or just a bit damp, one can stretch it out a bit on a niddy-noddy. Putting the wool back on the niddy-noddy makes for a nicer looking finished skein. Before taking a skein and washing it, the skein must be tied up loosely in about six places. If the skein is not tied up, it will be very hard to unravel when done washing.

Silk

Silk fabric was first developed in ancient China, with some of the earliest examples found as early as 3500 BC.

Cultivation

Silk moths lay eggs on specially prepared paper. The eggs hatch and the caterpillars (silkworms) are fed on fresh mulberry leaves. After about 35 days and 4 moltings, the caterpillars are 10,000 times heavier than when hatched and are ready to begin spinning a cocoon. A straw frame is placed over the tray of caterpillars, and each caterpillar begins spinning a cocoon by moving its head in a pattern. Two glands produce liquid silk and force it through openings in the head called spinnerets. Liquid silk is coated in sericin, a water-soluble protective gum, and solidifies on contact with the air. Within 2–3 days, the caterpillar spins about 1 mile of filament and is completely encased in a cocoon.[4]

Harvesting

The silk farmers then kill most caterpillars by heat, leaving some to metamorphose into moths to breed the next generation of caterpillars. Harvested cocoons are then soaked in boiling water to soften the sericin holding the silk fibres together in a cocoon shape.[4]

Throwing

The fibres are then unwound to produce a continuous thread. Since a single thread is too fine and fragile for commercial use, anywhere from three to ten strands are bundled together to form a single thread of silk.[4] Colloquially silk throwing can be used to refer to the whole process: reeling, throwing and doubling,[5] and silk throwsters would speak of throwing as twisting or spinning.[6]

Silk throwing was originally a hand process relying on a turning a wheel (the gate) that twisted four threads while a helper who would be a child, ran the length of a shade, hooked the threads on stationary pins (the cross)and ran back to start the process again. The shade would be a between 23 and 32m long.[7][8] The process was described in detail to Lord Shaftesbury's Royal Commission of Inquiry into the Employment of Children in 1841:

For twisting it is necessary to have what are designated shades which are buildings of at least 30 or 35 yards in length, ... the upper storey is generally occupied by children, ... or grown women as 'piecers', 'winders' and 'doublers' attending to their reels and bobbins [which is], driven by the exertions of one man... He (the boy) takes first a rod containing four bobbins of silk from the twister who stands at his gate or wheel, and having fastened the ends, runs to the 'cross' at the extreme end of the room, round which he passes the threads of each bobbin and returns to the 'gate'. He is despatched on a second expedition of the same kind, and returns as before, he then runs up to the cross and detaches the threads and comes to the roller. Supposing the master to make twelve rolls a day, the boy necessarily runs fourteen miles, and this is barefooted.[9]

In 1700, the Italians were the most technologically advanced throwsters in Europe and had developed two machines capable of winding the silk onto bobbins while putting a twist in the thread. They called the throwing machine, a filatoio, and called the doubler, a torcitoio. There is an illustration of a circular hand-powered throwing machine drawn in 1487 with 32 spindles. The first evidence of an externally powered filatoio comes from the thirteenth century, and the earliest illustration from around 1500.[9] Filatorios and torcitoios contained parallel circular frames that revolved round each other on a central axis. The speed of the relative rotation determined the twist. Silk would only cooperate in the process if the temperature and humidity were high.[7]

Fabric formation

Once the fibre has been turned into yarn the process of making cloth is much the same for any type of fibre, be it animal or plant.

Weaving

The earliest weaving was done without a loom.

Loom

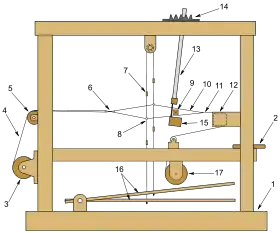

| Elements of a foot-treadle floor loom |

|

In general the supporting structure of the loom is called the frame. It provides the means of fixing the length-wise threads, called the warp, and keeping them under tension. The warp threads are wound on a roller called the warp beam, and attached to the cloth beam which will hold the finished material. Because of the tension the warp threads are under, they need to be strong.

The thread that is woven through the warp is called the weft. The weft is threaded through the warp using a shuttle. The original hand-loom was limited in width by the weaver's reach, because of the need to throw the shuttle from hand to hand. The invention of the flying shuttle with its fly cord and picking sticks enabled the weaver to pass the shuttle from a box at either side of the loom with one hand, and across a greater width. The invention of the drop box allowed a weaver to use multiple shuttles to carry different wefts.

Alternating sets of threads are lifted by connecting them with string or wires called heddles to another bar, called the shaft (or heddle bar or heald). Heddles, shafts and the couper (lever to lift the assembly) are called the harness — the harness provides for mechanical operation using foot- or hand-operated treadles. After passing a weft thread through the warp, a reed comb is used to beat (compact) the woven weft.[10]

To prepare to weave, the warp must be made. By hand this is done with the help of a warping board. The length the warp is made is about a quarter to half yard more than the amount of cloth needed. Warping boards come in a variety of shapes, from the two nearest door handles to a board with pegs on it, or a device called a warping mill that looks similar to a swift.[10] Warping the loom, mean threading each end through an eye in a heddle, and then sleying it through the reed. The warp is set (verb) at X ends per inch. It then has a sett (noun) of X ends per inch. The weft is measured in picks per inch.

Knitting

Hand knitting can either be done "flat" or "in the round". Flat knitting is done on a set of single point knitting needles, and the knitter goes back and forth, adding rows. In circular knitting, or "knitting in the round", the knitter knits around a circle, creating a tube. This can be done with a set of four double pointed needles or a single circular needle.

A knitted object will unravel easily if the top has not been secured. Knitted objects also stretch easily in all directions, whereas woven fabric stretches only on the bias.

Crocheting

Crocheting differs largely from knitting in that there is only one loop, not the multitude as knitting has. Also, instead of knitting needles, a crochet hook is used.

Lace making

A lace fabric is lightweight openwork fabric, patterned, with open holes in the work. The holes can be formed via removal of threads or cloth from a previously woven fabric, but more often lace is built up from a single thread and the open spaces are created as part of the lace fabric. Lace may be crocheted tatted,or knitted.

Textile finishing

Wet processes

Embroidery

Embroidery – threads which are added to the surface of a finished textile.

Embroidery is the handicraft of decorating fabric or other materials with needle and thread or yarn. Embroidery may also incorporate other materials such as metal strips, pearls, beads, quills, and sequins. Embroidery is most often used on caps, hats, coats, blankets, dress shirts, denim, stockings, and golf shirts. Embroidery is available with a wide variety of thread or yarn color.

See also

References

Citations

- ↑ "Designing for Fair Trade". People Tree. Archived from the original on 28 August 2008. Retrieved 12 February 2009.

- ↑ Atlas Obscura

- ↑ Australian Government Office of the Gene Technology Regulator (2 February 2008). "The Biology of Gossypium hirsutum L. and Gossypium barbadense L. (cotton)" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 25 June 2008.

- 1 2 3 Carrie Gleason: The Biography of Silk, page 12. Crabtree Publishing Company 2007.

- ↑ Calladine & Fricker 1993.

- ↑ Bednall 2008, p. 12.

- 1 2 Calladine & Fricker 1993, pp. 22–26.

- ↑ Collins & Stevenson 1995, p. 8

- 1 2 Calladine & Fricker 1993, p. 19.

- 1 2 "Weaving Terms" (PDF). Handwoven Magazine. Interweave Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2 January 2010. Retrieved 1 March 2008.

Bibliography

- Transcribed by A.W. Bednall. "A Day at The Derby Silk Mill" (PDF). The Penny Magazine. Society for the Diffusion of Useful Knowledge. XII (711): 161 to 168. July 2008 [1843].

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - Calladine, Anthony; Fricker, Jean (1993). East Cheshire Textile Mills. London: Royal Commission on Historical Monuments of England. ISBN 1-873592-13-2.

- Collins, Louanne; Stevenson, Moira (1995). Macclesfield: The Silk Industry. Images of England. Macclesfield Museums Trust (New Pocket Edition 2006 ed.). Stroud, Gloucester: Nonsuch Publishing Limited. ISBN 1-84588-294-6.

External links

- https://beecker-erlebnismuseen.de/historical-flax-to-linen/ (Explanatory videos from flax to linen)