Mention of textiles in folklore is ancient, and its lost mythic lore probably accompanied the early spread of this art. Textiles have also been associated in several cultures with spiders in mythology.

Weaving begins with spinning. Until the spinning wheel was invented in the 14th century, all spinning was done with distaff and spindle. In English the "distaff side" indicates relatives through one's mother, and thereby denotes a woman's role in the household economy. In Scandinavia, the stars of Orion's belt are known as Friggjar rockr, "Frigg’s distaff".

The spindle, essential to the weaving art, is recognizable as an emblem of security and settled times in a ruler's eighth-century BCE inscription at Karatepe:

"In those places which were formerly feared, where a man fears... to go on the road, in my days even women walked with spindles"

In the adjacent region of North Syria, historian Robin Lane Fox remarks funerary stelae showing men holding cups as if feasting and women seated facing them and holding spindles.[1]

Egypt

In pre-Dynastic Egypt, nt (Neith) was already the goddess of weaving (and a mighty aid in war as well). She protected the Red Crown of Lower Egypt before the two kingdoms were merged, and in Dynastic times she was known as the most ancient one, to whom the other gods went for wisdom. According to E. A. Wallis Budge (The Gods of the Egyptians) the root of the word for weaving and also for being are the same: nnt.

Easton's Bible Dictionary (1897) refers to numerous Biblical references to weaving:

Weaving was an art practised in very early times (Ex 35:35). The Egyptians were specially skilled in it (Isa 19:9; Ezek 27:7), and some have regarded them as its inventors.

In the wilderness, the Hebrews practised weaving (Ex 26:1, 26:8; 28:4, 28:39; Lev 13:47). It is referred to subsequently as specially the women's work (2 Kings 23:7; Prov 31:13, 24). No mention of the loom is found in Scripture, but we read of the "shuttle" (Job 7:6), "the pin" of the beam (Judg 16:14), "the web" (13, 14), and "the beam" (1 Sam 17:7; 2 Sam 21:19

Greece

In Greek mythology, the Moirai (the "Fates") are the three crones who control destiny, by spinning the thread of life on the distaff. Ariadne, princess of Minoan Crete and later the wife of the god Dionysus, possessed the spun thread that led Theseus to the center of the labyrinth and safely out again.

Among the Olympians, the weaver goddess is Athena, who, despite her role, was bested by her acolyte Arachne, whom Athena in retribution turned into a weaving spider.[2] The daughters of Minyas, Alcithoe, Leuconoe and their sister, defied Dionysus and honored Athena in their weaving instead of joining his festival. A woven peplos, laid upon the knees of the goddess's iconic image, was central to festivals honoring both Athena at Athens, and Hera.

In Homer's legend of the Odyssey, Penelope the faithful wife of Odysseus was a weaver, weaving her design for a shroud by day, but unravelling it again at night, to keep her suitors from claiming her during the long years while Odysseus was away; Penelope's weaving is sometimes compared to that of the two weaving enchantresses in the Odyssey, Circe and Calypso. Helen is at her loom in the Iliad to illustrate her discipline, work ethic, and attention to detail.

Homer dwells upon the supernatural quality of the weaving in the robes of goddesses.

In Roman literature, Ovid in his Metamorphoses (VI, 575–587) recounts the terrible tale of Philomela, who was raped and her tongue cut out so that she could not tell about her violation, her loom becomes her voice, and the story is told in the design, so that her sister Procne may understand and the women may take their revenge. The understanding in the Philomela myth that pattern and design convey myth and ritual has been of great use to modern mythographers: Jane Ellen Harrison led the way, interpreting the more permanent patterns of vase painting, since the patterned textiles had not survived.

Germanic

For the Norse peoples, Frigg is a goddess associated with weaving. The Old Norse Darraðarljóð, quoted in Njals Saga, gives a detailed description of valkyries as women weaving on a loom, with severed heads for weights, arrows for shuttles, and human gut for the warp, singing an exultant song of carnage. Ritually deposited spindles and loom parts were deposited with the Pre-Roman Iron Age Dejbjerg wagon, a composite of two wagons found ritually deposited in a peat bog in Dejbjerg, Jutland,[3] and are to be associated with the wagon-goddess.

In Germanic later mythology, Holda (Frau Holle) and Perchta (Frau Perchta, Berchta, Bertha) were both known as goddesses who oversaw spinning and weaving. They had many names.

Holda, whose patronage extends outward to control of the weather, and source of women's fertility, and the protector of unborn children, is the patron of spinners, rewarding the industrious and punishing the idle. Holda taught the secret of making linen from flax. An account of Holda was collected by the Brothers Grimm, as the fairy tale "Frau Holda". Another of the Grimm tales, "Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle", which embeds social conditioning in fairy tale with mythic resonances, rewards the industrious spinner with the fulfillment of her mantra:

- "Spindle, my spindle, haste, haste thee away,

- and here to my house bring the wooer, I pray."

- "Spindel, Spindel, geh' du aus,

- bring den Freier in mein Haus."

This tale recounts how the magic spindle, flying out of the girl's hand, flew away, unravelling behind it a thread, which the prince followed, as Theseus followed the thread of Ariadne, to find what he was seeking: a bride "who is the poorest, and at the same time the richest". He arrives to find her simple village cottage magnificently caparisoned by the magically aided products of spindle, shuttle and needle.

Jacob Grimm reported the superstition "if, while riding a horse overland, a man should come upon a woman spinning, then that is a very bad sign; he should turn around and take another way." (Deutsche Mythologie 1835, v3.135)

Celts

The goddess Brigantia, due to her identification with the Roman Minerva, may have also been considered, along with her other traits, to be a weaving deity.

French

Weavers had a repertory of tales: in the 15th century Jean d'Arras, a Northern French storyteller (trouvere), assembled a collection of stories entitled Les Évangiles des Quenouilles ("Spinners' Tales"). Its frame story is that these are narrated among a group of ladies at their spinning.[4]

Baltic

In Baltic myth, Saule is the life-affirming sun goddess, whose numinous presence is signed by a wheel or a rosette. She spins the sunbeams. The Baltic connection between the sun and spinning is as old as spindles of the sun-stone, amber, that have been uncovered in burial mounds. Baltic legends as told have absorbed many images from Christianity and Greek myth that are not easy to disentangle.

Finnish

The Finnish epic, the Kalevala, has many references to spinning and weaving goddesses.[5]

Later European folklore

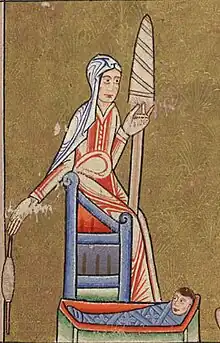

"When Adam delved and Eve span..." runs the rhyme; though the tradition that Eve span is unattested in Genesis, it was deeply engrained in the medieval Christian vision of Eve. In an illumination from the 13th-century Hunterian Psalter (illustration. left) Eve is shown with distaff and spindle.

In later European folklore, weaving retained its connection with magic. Mother Goose, traditional teller of fairy tales, is often associated with spinning.[6] She was known as "Goose-Footed Bertha" or Reine Pédauque ("Goose-footed Queen") in French legends as spinning incredible tales that enraptured children.

The daughter who, her father claimed, could spin straw into gold and was forced to demonstrate her talent, aided by the dangerous earth-daemon Rumpelstiltskin was an old tale when the Brothers Grimm collected it. Similarly, the unwilling spinner of the tale The Three Spinners is aided by three mysterious old women. In The Six Swans, the heroine spins and weaves starwort in order to free her brothers from a shapeshifting curse. Spindle, Shuttle, and Needle are enchanted and bring the prince to marry the poor heroine. Sleeping Beauty, in all her forms, pricks her finger on a spindle, and the curse falls on her.[7]

In Alfred Tennyson's poem "The Lady of Shalott", her woven representations of the world have protected and entrapped Elaine of Astolat, whose first encounter with reality outside proves mortal. William Holman Hunt's painting from the poem (illustration, right) contrasts the completely pattern-woven interior with the sunlit world reflected in the roundel mirror. On the wall, woven representations of Myth ("Hesperides") and Religion ("Prayer") echo the mirror's open roundel; the tense and conflicted Lady of Shalott stands imprisoned within the brass roundel of her loom, while outside the passing knight sings "'Tirra lirra' by the river" as in Tennyson's poem.

A high-born woman sent as a hostage-wife to a foreign king was repeatedly given the epithet "weaver of peace", linking the woman's art and the familiar role of a woman as a dynastic pawn. A familiar occurrence of the phrase is in the early English poem Widsith, who "had in the first instance gone with Ealhild, the beloved weaver of peace, from the east out of Anglen to the home of the king of the glorious Goths, Eormanric, the cruel troth-breaker..."

Inca

In Inca mythology, Mama Ocllo first taught women the art of spinning thread.

China

- In Tang dynasty China, the goddess weaver floated down on a shaft of moonlight with her two attendants. She showed the upright court official Guo Han in his garden that a goddess's robe is seamless, for it is woven without the use of needle and thread, entirely on the loom. The phrase "a goddess's robe is seamless" passed into an idiom to express perfect workmanship. This idiom is also used to mean a perfect, comprehensive plan.

- The Goddess Weaver, daughter of the Celestial Queen Mother and Jade Emperor, wove the stars and their light, known as "the Silver River" (what Westerners call "The Milky Way Galaxy"), for heaven and earth. She was identified with the star Westerners know as Vega. In a 4,000-year-old legend, she came down from the Celestial Court and fell in love with the mortal Buffalo Boy (or Cowherd), (associated with the star Altair). The Celestial Queen Mother was jealous and separated the lovers, but the Goddess Weaver stopped weaving the Silver River, which threatened heaven and earth with darkness. The lovers were separated, but are able to meet once a year, on the seventh day of the seventh moon.[8]

Japan

- The Japanese folktale Tsuru no Ongaeshi features a weaving theme. A crane, rescued by a childless elderly couple, appears to them in the guise of a girl who cares for them out of gratitude for their kindness and is adopted as their daughter. She secretly begins weaving stunningly beautiful cloth for the couple to sell under the condition that they may not see her weave. Though the couple initially comply, they are overcome with curiosity and find the girl is the crane who has been weaving the cloth from her own feathers, leaving her in a pitiful state. With her identity discovered, she must leave the remorseful couple. A variation of the story replaces the elderly couple with a man, who marries the crane when she takes on the form of a young woman.

Christian hagiography

Multiple individuals have been designated as patron saints of various aspects of textile work. The mythology and folklore surrounding their patronage can be found in their respective hagiographies.

According to the Gospel of James, the Blessed Virgin Mary was weaving the veil for the Holy of Holies when the Annunciation occurred.[9]

- Textiles generally: Anthony Mary Claret is a Catholic patron saint of textile merchants. Saint Homobonus is a Catholic patron saint of tailors and clothworkers. Saint Maurice is considered a patron saint of weavers, dyers, and clothmaking in general in Coptic Orthodoxy, Oriental Orthodoxy, the Roman Catholic Church, and the Eastern Orthodox Church. Parascheva of the Balkans is a patron of embroiderers, needle workers, spinners, and weavers among the Eastern Orthodox.

- Drapers: St. Blaise is the patron saint of drapers.

- Dyers: Lydia of Thyatira, a New Testament figure, is a patron saint of dyers in both Catholic and Eastern Orthodox traditions. Saint Maurice is also associated with dyers.

- Fulling: Anastasius the Fuller is the patron saint of fulling in the Catholic Church.

- Glovers: Mary Magdalene is a patron saint of glovers in the Roman Catholic and Eastern Orthodox Church. Gummarus is a patron saint of glovers in the Catholic church. Saints Crispin and Crispinian are Eastern Orthodox patron saints of glovers.

- Hosiers: Saint Fiacre is the patron saint of hosiers.

- Lacework: Saints Crispin and Crispinian are considered patron saints of lacework.

- Laundry and laundry workers: Clare of Assisi and Saint Veronica are the patron saints of laundry and laundry workers.

- Millinery: Severus of Avranches is the Catholic patron saint of millinery.

- Needlework: Clare of Assisi is the patron saint of needlework, and Rose of Lima is the patron saint of embroidery, a specific type of needlework. Parascheva of the Balkans is the patron saint of needlework and other aspects of textiles among the Eastern Orthodox.

- Pursemakers: Saint Brioc is the patron saint of pursemakers.

- Seamstresses: Saint Anne is regarded as the patron saint of seamstresses in both Eastern Orthodox and Roman Catholic traditions.

- Silk workers: Severus of Avranches is the Catholic patron saint of silk workers.

- Spinning: Saint Catherine is the patron saint of spinners.

- Tapestry workers: Francis of Assisi is the patron saint of tapestry workers.

- Weaving: Onuphrius is considered a patron saint of weaving in Coptic, Eastern, and Oriental Orthodoxy as well as Catholic traditions. Saint Maurice and Parascheva of the Balkans are also patrons of weaving, as is Severus of Avranches.

- Wool workers: Saint Blaise is a patron saint of wool workers revered by the Catholic, Eastern Orthodox, and Oriental Orthodox traditions. Severus of Avranches is also considered a patron saint of wool workers by Catholics.

See also

References

- ↑ Quoted and noted in Fox, Robin Lane (2008). Travelling Heroes in the Epic Age of Homer. Vintage Books. p. 77. ISBN 978-0-679-76386-4

- ↑ "Athena | Greek mythology". Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ↑ Found in the 1880s; noted by Grigsby, John (2005). Beowulf and Grendel: the Truth behind England's Oldest Myth. Watkins. p. 57, 113f. ISBN 1-84293-153-9. See discussion of the ritual wagons in Danish bogs in Glob, Peter Vilhelm & Bruce-Mitford, Rupert (transl.) (1988). The Bog People: Iron-Age Man Preserved. New York Review. pp. 166-71. ISBN 1-59017-090-3.

- ↑ Jeay, Madeleine; Garay, Kathleen (2006-01-01). The Distaff Gospels: A First Modern English Edition of Les Évangiles des Quenouilles. Broadview Press. ISBN 9781551115603.

- ↑ "Kalevala | Finnish literature". Retrieved 2016-09-29.

- ↑ Tatar, Maria (1987). The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales. p. 114. ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ↑ Tatar, Maria (1987). The Hard Facts of the Grimms' Fairy Tales. pp. 115–8, ISBN 0-691-06722-8

- ↑ Jung Chang, Wild Swans: Three Daughters of China, New York: Touchstone, 2003, reprint, GlobalFlair, 1991, p. 429, accessed 2 Nov 2009

- ↑ "CHURCH FATHERS: Protoevangelium of James". www.newadvent.org. Retrieved 2019-01-31.

Further reading

- Barber, Elizabeth Wayland (1991). Prehistoric Textiles: The Development of Cloth in the Neolithic and Bronze Ages with Special Reference to the Aegean. Princeton: Princeton University Press. ISBN 0-691-03597-0

- Scheid, John, and Jesper Svenbro (1996). The Craft of Zeus: Myths of Weaving and Fabric. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. ISBN 0-674-17549-2

- Weigle, Marta (2007, 1982). Spiders and Spinsters: Women and Mythology. Santa Fe: Sunstone Press. ISBN 978-0-86534-587-4

- Volkmann, Helga (2008). Purpurfäden und Zauberschiffchen: Spinnen und Weben in Märchen und Mythen. Göttingen: Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-525-20858-8

External links

Media related to Textiles in mythology and folklore at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Textiles in mythology and folklore at Wikimedia Commons