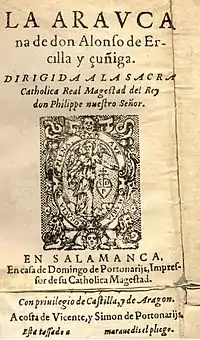

La Araucana (also known in English as The Araucaniad) is a 16th-century epic poem[1] in Spanish by Alonso de Ercilla, about the Spanish Conquest of Chile.[2] It was considered the national epic of the Captaincy General of Chile and one of the most important works of the Spanish Golden Age (Siglo de Oro).[3] It was translated into English in 1945 by Paul Thomas Manchester and Charles Maxwell Lancaster for Vanderbilt University Press.[4]

The poem

Structure

La Araucana consists of 37 cantos that are distributed across the poem's three parts.[5] The first part was published in 1569; the second part appeared in 1578, and it was published along with the first part; the third part was published with the first and second parts in 1589. The poem shows Ercilla to be a master of the octava real (that is Italian ottava rima), the complicated stanza in which many other Renaissance epics in Castilian were written. A difficult eight-line unit of 11-syllable verses that are linked by a tight rhyme scheme abababcc, the octava real was a challenge few poets met. It had been adapted from Italian only in the 16th century.

Subject matter

The work describes the initial phase of the Arauco War which evolved from the Spanish conquest attempt of southern Chile. The war would come to shape the economics, politics and social life of Chile for centuries. Ercilla placed the lesser conquests of the Spanish in Chile at the core of his poem, because the author was a participant in the conquest and the story is based on his experiences there.

Development

On scraps of paper in the lulls of fighting, Ercilla jotted down versified octaves about the events of the war and his own part in it. These stanzas he later gathered together and augmented in number to form his epic. In the minds of the Chilean people La Araucana is a kind of Iliad that exalts the heroism, pride, and contempt of pain and death of the legendary Araucanian leaders and makes them national heroes today. Thus we see Ercilla appealing to the concept of the "noble savage," which has its origins in classical authors and took on a new lease of life in the renaissance – c.f. Montaigne's essay "Des Canibales", and was destined to have wide literary currency in European literature two centuries later. He had, in fact, created a historical poem of the war in Chile which immediately inspired many imitations.

Influences

La Araucana is deliberately literary and includes fantastical elements reminiscent of medieval stories of chivalry. The narrator is a participant in the story, at the time a new development for Spanish literature. Influences include Orlando furioso by Ludovico Ariosto. Also features extended description of the natural landscape. La Araucana’s successes—and weaknesses—as a poem stem from the uneasy coexistence of characters and situations drawn from Classical sources (primarily Virgil and Lucan, both translated into Spanish in the 16th century) and Italian Renaissance poets (Ludovico Ariosto and Torquato Tasso) with material derived from the actions of contemporary Spaniards and Araucanians.

The mixture of Classical and Araucanian motifs in La Araucana often strikes the modern reader as unusual, but Ercilla's turning native peoples into ancient Greeks, Romans, or Carthaginians was a common practice of his time. For Ercilla, the Araucanians were noble and brave—only lacking, as their Classical counterparts did, the Christian faith. Caupolicán, the Indian warrior and chieftain who is the protagonist of Ercilla's poem, has a panoply of Classical heroes behind him. His valour and nobility give La Araucana grandeur, as does the poem's exaltation of the vanquished: the defeated Araucanians are the champions in this poem, which was written by one of the victors, a Spaniard. Ercilla's depiction of Caupolicán elevates La Araucana above the poem's structural defects and prosaic moments, which occur toward the end when Ercilla follows Tasso too closely and the narrative strays from the author's lived experience. Ercilla, the poet-soldier, eventually emerges as the true hero of his own poem, and he is the figure that gives the poem unity and strength.

The story is considered to be the first or one of the first works of literature in the New World (cf. Cabeza de Vaca's Naufragios—"Shipwrecked" or "Castaways") for its fantastical/religious elements, it is arguable whether that is a "traveler's account" or actual literature; and Bernal Díaz del Castillo's Historia verdadera de la conquista de Nueva España (The Conquest of New Spain). La Araucana’s more dramatic moments also became a source of plays. But the Renaissance epic is not a genre that has, as a whole, endured well, and today Ercilla is little known and La Araucana is rarely read except by specialists and students of Spanish and Latin American literatures, and of course in Chile, where it is subject of special attention in the elementary schools education both in language and history.

The author

Alonso de Ercilla was born into a noble family in Madrid, Spain.[6] He occupied several positions in the household of Prince Philip (later King Philip II of Spain), before requesting and receiving appointment to a military expedition to Chile to subdue the Araucanians of Chile, he joined the adventurers. He distinguished himself in the ensuing campaign; but, having quarrelled with a comrade, he was condemned to death in 1558 by his general, García Hurtado de Mendoza. The sentence was commuted to imprisonment, but Ercilla was speedily released and fought at the Battle of Quipeo (14 December 1558). He was then exiled to Peru and returned to Spain in 1562.

Reception

Ercilla embodied the Renaissance ideal of being at once a man of action and a man of letters as no other in his time was. He was adept at blending personal, lived experience with literary tradition. He was widely acclaimed in Spain. There is an episode in Miguel de Cervantes’s 17th-century novel Don Quixote, when a priest and barber inspect Don Quixote's personal library, to burn the books responsible for driving him to madness. La Araucana is one of the works which the men spare from the flames, as "one of the best examples of its genre", entirely Christian and honorable, and is proclaimed to be among the best poems in the heroic style ever written, good enough to compete with those of Ariosto and Tasso.

Voltaire was much more critical, describing the poem as rambling and directionless and calling the author more barbarous than the Indians whom it is about. He does, however, express admiration for the speech in Canto II, which he compares favorably to Nestor's speech in the Iliad.[7]

In 1858, the French lawyer Antoine de Tounens, after reading the book in French translation, decided to go to South America to proclaim the kingdom of Araucanía and Patagonia with him as king. The de Tounens gained the support of a few Mapuche leaders who proclaimed him king but his kingship and kingdom was never recognized by Chile, Argentina or the European states.

Events

A revolt starts when the conqueror of Chile, Pedro de Valdivia is captured and killed by Mapuche (also known as Araucanian) Indians. Ercilla blames Valdivia for his own death, having mistreated the natives who had previously acquiesced to Spanish rule and provoking them into rebellion. However, having previously accepted the rule of Charles V, Holy Roman Emperor, the Araucanians were now in revolt against their legitimate sovereign lord. This is the ethical position of Ercilla: sympathy for the Indians' suffering, admiration for the courage of their resistance, criticism of Spanish cruelty, but loyalty to and acceptance of the legitimacy of the Spanish cause (the legitimate rule of a duly-constituted prince and the extension of Christianity). Although Ercilla's purpose was to glorify Spanish arms, the figures of Araucanian chiefs, the strong Caupolicán, the brilliant Lautaro, the old and wise Colocolo and the proud Galvarino, have proved the most memorable.

Key events include the capture and execution of Pedro de Valdivia; the death of the hero Lautaro in the Battle of Mataquito, and the execution of Caupolicán the Toqui for leading the revolt of the Araucanians (thanks to betrayal by one of their own); the encounter with a sorcerer who takes the narrator for a flight above the earth to see events happening in Europe and the Middle East; and the encounter with an Indian woman (Glaura) searching for her husband amongst the dead after a battle. This last is an indicator of the humanist side of Ercilla, and a human sympathy which he shows towards the indigenous people. The narrator claims that he attempted to have the life of the Indian chieftain spared.

The historicity of some events and characters have been put into question. Historian Diego Barros Arana has argued that the female character Janequeo is an invention that passed down without scrutiny as historical in the chronicles of the Jesuits Alonso de Ovalle and Diego de Rosales.[8]

See also

References

- ↑ Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga: La Araucana (in Spanish).

- ↑ Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, Spanish soldier and poet, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga, Spanish soldier and poet, Encyclopædia Britannica.

- ↑ Zuniga, Alonso de Ercilla y (2021-04-30). The Araucaniad. Vanderbilt University Press. ISBN 978-0-8265-0304-6.

- ↑ Alonso de Ercilla y Zúñiga: La Araucana (in Spanish).

- ↑ Alonso de Ercilla, Biografías y Vidas.

- ↑ Voltaire, en Essai Sur la Poesie Epique, prefacio de la edición virtual de La Araucana, Pehuen Editores.

- ↑ Diego Barros Arana, Historia general de Chile.

Sources

- Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1913). . Catholic Encyclopedia. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- Lerner, Isias (1989). "Don Alonso de Ercilla y Zuniga". In Solé, Carlos A (ed.). Latin American Writers. Macmillan Publishing House. pp. 23–35. ISBN 0684185970.

- This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). "Ercilla y Zúniga, Alonso de". Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 734.