| The Archangel Michael | |

|---|---|

| Greek: Ο Αρχάγγελος Μιχαήλ, Italian: L'Arcangelo Michele | |

| |

| Artist | Theodore Poulakis |

| Year | c. 1640–1692 |

| Medium | tempera on wood |

| Movement | Heptanese School |

| Subject | The Archangel Michael |

| Dimensions | 76 cm × 54.3 cm (29.92 in × 21.37 in) |

| Location | Benaki Museum, Athens, Greece |

| Owner | Benaki Museum |

| Accession | ΓΕ 3007 |

| Website | Official Website |

The Archangel Michael was created by Greek painter Theodore Poulakis. He was also a teacher. He was affiliated with Greek painter Philotheos Skoufos. Poulakis was active on the Ionian Islands and Venice. He studied painting in Venice for over a decade. He was also involved with Venetian politics. He was a member of the quarantia. He was a representative of two schools, the Cretan School and Heptanese School. He is considered one of the founding members of the Heptanese School along with Elias Moskos. One hundred thirty of his paintings survived.[1]

The Archangel Micheal is a biblical figure associated with the old testament. The earliest surviving documented usage of his name is from 3rd and 2nd-century Hebrew texts. He is often associated with the apocalypse. He is often the chief of the angels and archangels. He is typically responsible for the care of humanity.[2][3][4] [5] Christianity adopted old testament traditions concerning the Archangel. [6] Michael is mentioned explicitly in Revelation 12:7–12,[7] where he battles Satan.[8] He has been depicted in Greek Italian Byzantine art since the dawn of the new religion.

Cretan Renaissance art and Baroque Roccoco Ionian art was heavily influenced by Italian art. One exemplary depiction of the Archangel was completed by Italian painter Raphael in his world-famous painting entitled St. Michael Vanquishing Satan. Elias Moskos also completed a version of the Archangel. Poulaki's version is a blend of both Italian and Greek prototypes. The work of art lies on the boundary of the Late Cretan School and Early Heptanese School. The work of art is at the Benaki Museum in Athens Greece.[9][10]

Description

The materials used for The Archangel Michael were tempera and gold leaf on wood panel. The height of the painting is 76 cm (29.92 in) and the width is 54.3 cm (21.37 in). The work of art follows the traditional maniera greca but the style is far more advanced than Byzantine and Cretan art. The painter employs an advanced painting style that evolved on the Ionian Islands. The masterpiece has roots in the Late Cretan School. The gilded gold background is still intact. Raphael and his contemporaries chose to remove the majestic exalting divine gold background for a more natural setting utilizing the background, foreground, and middle ground.

Poulaki's painting superfluously venerates the Archangel and constructs a sculpturesque figure dressed in a lavish costume, with luxuriant patterns and brilliant colors. His cape floats creating a weightless setting. The artist employs an advanced shadowing method. Poulakis adds dimension to the shallow stage for the figures.

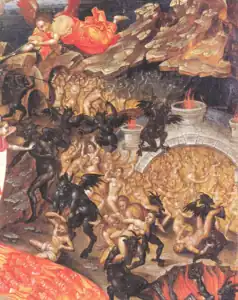

The Archangel's legs stand on a wolflike demon. The wolflike demonic figure is present in the works of Leos Mosko's The Last Judgment, Georgios Klontza's The Last Judgment, and Poulaki's In Thee Rejoiceth . The wolflike demon captivates the audience with its expression of fright and terror. The Archangel suppresses and subjugates the powerful demonic entity with his exquisitely painted Lance, historically referred to as The Lance of Michael. The painter was an expert in the cangiante. The demonic figure is muscular, the hairs are a brilliant variation of brown. The brushstrokes of his fur clearly demonstrate grooves, lines, and contours. The painter clearly reveals the creature's hair as he floats on a pool of fire. The monster's paw and nails are grasping for The Lance of Michael. The painting is signed in the lower right-hand corner.[11]

Gallery

References

- ↑ Hatzidakis, Manolis; Drakopoulou, Evgenia (1997). Έλληνες Ζωγράφοι μετά την Άλωση (1450–1830). Τόμος 2: Καβαλλάρος – Ψαθόπουλος [Greek Painters after the Fall of Constantinople (1450–1830). Volume 2: Kavallaros – Psathopoulos]. Athens: Center for Modern Greek Studies, National Research Foundation. pp. 304–317. hdl:10442/14088. ISBN 960-7916-00-X.

- ↑ Asale 2020, p. 55.

- ↑ Hannah 2011, p. 33-54.

- ↑ Hannah 2011, p. 33.

- ↑ Barnes 1993, p. 54.

- ↑ Hannah 2011, p. 54.

- ↑ Revelation 12:7–12

- ↑ Bromiley 1971, p. 156-157.

- ↑ Staff Writers (June 6, 2022). "The Archangel Michael". Benaki Museum. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ↑ Staff Writers (June 6, 2022). "Αρχάγγελος Μιχαήλ (Archangel Michael)". Europeana. Retrieved June 6, 2022.

- ↑ Rēgopoulos, Iōannēs K; Poulakis, Theodore (1979). Ο Αγιογράφος Θεόδωρος Πουλάκης και η Φλαμανδική Χαλκογραφία [The Hagiographer Theodore Poulakis and Flemish Engravings]. Athens, Greece: Ekdoseis Grēgorē. p. 139. ISBN 9789602040348.

Bibliography

- Asale, Bruk Ayele (2020). 1 Enoch as Christian Scripture. Pickwick. ISBN 9781532691157.

- Barnes, William H. (1993). "Archangels". In Coogan, Michael David; Metzger, Bruce M. (eds.). The Oxford Companion to the Bible. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199743919.

- Bromiley, Geoffrey William · (1971). "Satan". Theological Dictionary of the New Testament. Vol. 7. Alban Books. ISBN 9780802822499.

- Hannah, Darrell D. (2011). Michael and Christ: Michael Tradition and Angel Christology. Wipf and Stock. ISBN 9781610971539.