| The Dalles Lock and Dam | |

|---|---|

From the Washington side | |

| Official name | The Dalles Lock and Dam |

| Location | Klickitat County, Washington / Wasco County, Oregon, USA |

| Coordinates | 45°36′49″N 121°08′00″W / 45.61361°N 121.13333°W |

| Construction began | 1952 |

| Opening date | 1957 |

| Operator(s) | U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (Operator) Bonneville Power Administration (Marketer) |

| Dam and spillways | |

| Type of dam | Concrete gravity, run-of-the-river |

| Height | 200 ft (61 m) |

| Length | 8,835 ft (2,693 m) |

| Width (base) | 239 ft (73 m) (Spillway) |

| Spillway type | Service, gate-controlled |

| Spillway capacity | 2,290,000 cu ft/s (65,000 m3/s) |

| Reservoir | |

| Creates | Lake Celilo |

| Total capacity | 330,000 acre⋅ft (0.41 km3) |

| Power Station | |

| Turbines | 22 |

| Installed capacity | 1,878.3 MW Max.: 2,160 MW |

| Annual generation | 6,180 GWh[1] |

The Dalles Lock and Dam is a concrete-gravity run-of-the-river dam spanning the Columbia River, two miles (3 km) east of the city of The Dalles, Oregon, United States.[2] It joins Wasco County, Oregon with Klickitat County, Washington, 192 miles (309 km) upriver from the mouth of the Columbia near Astoria, Oregon. The closest towns on the Washington side are Dallesport and Wishram.

The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers (USACE) began work on the dam in 1952 and completed it five years later. Slack water created by the dam submerged Celilo Falls, the economic and cultural hub of Native Americans in the region and the oldest continuously inhabited settlement in North America.[3] Inhabitants of the submerged area include the Wasco–Wishram[4] and Skinpah.[5]

On March 10, 1957, hundreds of observers looked on as the rising waters rapidly silenced the falls, submerged fishing platforms, and consumed the village of Celilo. Ancient petroglyphs were also in the area being submerged. Approximately 40 petroglyph panels were removed with jackhammers before inundation and were placed in storage before being installed in Columbia Hills State Park in the 2000s.[6]

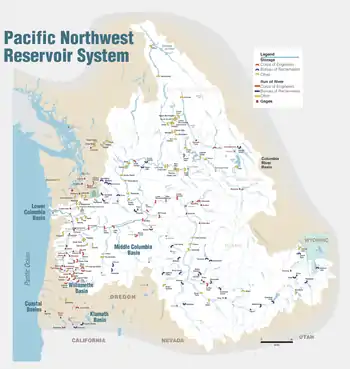

The reservoir behind the dam is named Lake Celilo and runs 24 miles (39 km) up the river channel, to the foot of John Day Dam. The dam is operated by the USACE, and the power is marketed by the Bonneville Power Administration (BPA). It is part of an extensive system of dams on the Columbia and Snake Rivers.

The Dalles Dam Visitor Center, in Seufert Park on the Oregon shore, was built in 1981. A tour train was closed in autumn 2001, partly due to post-September 11 security concerns, and partly due to deteriorating track conditions and a small derailment.[7] The Columbia Hills State Park is nearby.

The Dalles Dam is one of the ten largest hydroelectric dams in the United States. Along with hydro power, the dam provides irrigation water, flood mitigation, navigation, and recreation. The Dalles Lock and Dam has been designated as a National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark by the American Society of Civil Engineers.[8]

Environmental and social consequences

Prior to the construction of the dam, Celilo Falls was a hub for local Native American trading and fishing.[9] The area served as a spiritual monument as well, and continues to be the site of traditional ceremonies, during which people celebrate the end of winter and the beginning of the spring salmon run.[9]

The construction of the Dalles Dam was extremely damaging to salmon runs in the Columbia River. The physical dam makes it difficult for fish to navigate the river and reach their spawning grounds. Even with the installation of fish ladders, salmon populations have struggled.

Celilo Falls and the traditional rights of local Native American tribes to fish were protected by a government treaty,[9] but with the onset of the Cold War and the legacy of Bonneville Dam, completed in 1938,[10] the USACE looked to develop another hydro power production facility on the Columbia River. The Dalles' location on the mid-Columbia River below the falls made it an ideal hydro power production site. The Dalles Dam was authorized under the 1950 Flood Control Act, with the federal government able to work around the treaty with local tribes by paying them a settlement. However, despite assurances from the USACE that they would work to improve living conditions in Celilo as part of the settlement, these efforts failed for lack of attention by the federal government.[11]

Since 2016, the USACE has worked on The Dalles Lock & Dam Tribal Housing Village Development Plan. This plan is designed to find a location for and construct a village for members of the tribes that historically relied on Celilo Falls for fishing. The Village Development Plan had been slated to be finished by fall of 2020, however, as of April 2023 it has not been completed. In 2017, various senators from the states of Oregon and Washington signed a letter to the Director of the Office of Management and Budget, expressing concern about the Office's plan to halt the project.[12]

In 2007, the USACE conducted a sonar survey of the riverbed of Celilo Falls to determine whether the former site of the falls had been destroyed by the construction of the dam. The survey found that the geological features on the riverbed match those observed in photos of the falls prior to the construction of the dam. Hypothetically, this establishes that the falls would return if the dam were to be removed.[13]

Specifications

Gallery

Vice-President Richard Nixon speaking at The Dalles Dam dedication in 1959

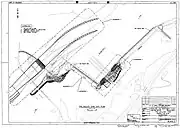

Vice-President Richard Nixon speaking at The Dalles Dam dedication in 1959 The Dalles Dam site plan

The Dalles Dam site plan Looking west, fish ladder in the foreground, power generation center. Mount Hood rises in the background.

Looking west, fish ladder in the foreground, power generation center. Mount Hood rises in the background. The Dalles Dam in June 1973

The Dalles Dam in June 1973

See also

References

- ↑ "Carbon Monitoring for Action | Center For Global Development". Archived from the original on 2014-03-18. Retrieved 2014-03-18.

- ↑ "The Columbia River System Inside Story" (PDF). BPA.gov. pp. 14–15. Archived from the original (PDF) on 27 May 2010. Retrieved 17 July 2010.

- ↑ Dietrich, William (1995). Northwest Passage: The Great Columbia River. Seattle, WA: University of Washington Press. p. 52.

- ↑ "Celilo Falls, Oregon". National Park Service. May 10, 2023. Archived from the original on October 2, 2023. Retrieved September 24, 2023.

- ↑ Hunn, Eugene S. (Winter 2007). "Sk'in, The Other Side of the River". Oregon Historical Quarterly. 108 (4): 614–623. doi:10.1353/ohq.2007.0028. S2CID 165209382.

- ↑ Banyasz, Malin Grunberg (May–Jun 2017). "Off the Grid". Archaeology. 70 (3): 10. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 3 July 2017 – via EBSCO's Master File Complete (subscription required)

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) - ↑ "About". The Dalles Dam Tour Train. Archived from the original on 2016-04-07. Retrieved 2023-10-02.

- ↑ Goodell, Christopher R. (Spring 2014). "The Dalles Dam – An ASCE National Historic Civil Engineering Landmark" (PDF). EWRI Currents. 17 (2): 6–9. Archived from the original on November 24, 2021. Retrieved November 24, 2021.

- 1 2 3 Barber, Katrine (2005-01-01). The Death of Celilo Falls. University of Washington Press. p. 272. ISBN 9780295800929.

- ↑ "Bonneville Dam and Lake Bonneville". www.nwd.usace.army.mil. Archived from the original on 2022-12-16. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ↑ "Portland District > Missions > Tribal Relationships > The Dalles Lock & Dam Tribal Housing Village Development Plan". www.nwp.usace.army.mil. Archived from the original on 16 December 2022. Retrieved 13 December 2022.

- ↑ "Letter" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2022-09-20. Retrieved 2022-12-16.

- ↑ Joe Rojas-Burke, The Oregonian (28 November 2008). "Sonar shows Celilo Falls are intact". oregonlive. Archived from the original on 2 October 2023. Retrieved 16 December 2022.

- 1 2 "The Dalles Lock and Dam". National Performance of Dams Program. Archived from the original on 7 March 2016. Retrieved 1 March 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 "The Dalles Lock and Dam Fact Sheet". United States Army Corps of Engineers. 2013. Archived from the original on 20 October 2020. Retrieved 25 September 2020.

External links

- The Dalles Lock & Dam – The U.S. Army Corps of Engineers

- "The Dalles Dam to Submerge Famous Indian Fishing Spot." Popular Mechanics, April 1956, pp. 138–140.