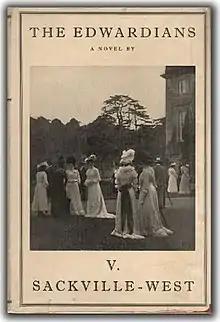

The Edwardians (1930) is one of Vita Sackville-West's later novels and a clear critique of the Edwardian aristocratic society as well as a reflection of her own childhood experiences. It belongs to the genre of the Bildungsroman and describes the development of the main character Sebastian within his social world, in this case the aristocracy of the early 20th century.

“I ... try to remember the smell of the bus that used to meet one at the station in 1908. The rumble of its rubberless tyres. The impression of waste and extravagance which assailed one the moment one entered the doors of the house. The crowds of servants; people’s names in little slits on their bedroom doors; sleepy maids waiting about after dinner in the passages. I find that these things are a great deal more vivid to me than many things which have occurred since, but will they convey anything whatever to anyone else? Still I peg on, and hope one day to see it all under the imprint of the Hogarth Press, in stacks in the bookshops.” (Letter from West to Virginia Woolf, July 24, 1929)[1]

Plot introduction

The story is mainly set at Chevron, an enormous country house and estate in the south of England, which is the ancestral seat of the Dukes of Chevron. In some passages the setting switches to London, for example when Sebastian visits Teresa. The plot covers the years of Sebastian's and Viola's adolescence which means approximately 1905–1910.

Plot summary

Sebastian is the 19-year-old Duke of Chevron and owner of the country estate of Chevron. As he had not yet attained his majority, the estate is presided over by his mother, Lucy, Dowager Duchess of Chevron. Being at home from Oxford at the weekends he regularly attends the magnificent parties given by his widowed mother, where the guests indulge in food, drinks, games and affairs.

At one of these parties he meets the adventurer Leonard Anquetil, who grew up under humble circumstances but managed to become well-known and socially acknowledged due to his several successful expeditions. During a deep conversation on top of Chevron’s roof Anquetil tries to open Sebastian’s eyes to the artificiality and hypocrisy of his mother’s aristocratic society and to convince the young heir to leave his social obligations behind in order to accompany Anquetil on an expedition. However, Sebastian is not impressed enough by the predictions made by Anquetil (affairs, marriage, service to the crown, but never being completely content) to turn his back on his safe home. One of the reasons for that is the love affair he had just started with Sylvia Roehampton, a married friend of his mother.

After Sylvia’s husband finds out about this relationship she, Lady Roehampton, leaves Sebastian and does not accept his offer to run away and start a new life together, since she does not want a public scandal and sticks to social conventions. Soon after, Sebastian plans to start an affair with Teresa Spedding, a doctor’s wife, but she eventually does not respond to Sebastian’s courtship. Yet coming from a middle-class background she is extremely impressed by and interested in aristocratic society. Sebastian, being disappointed and never seeming to be content, attempts to distract himself by having two more affairs with women from different classes. During the coronation ceremony of George V, which he attends, he finally gives in to the expectations and obligations his family history imposes on him and plans to marry a decent young lady and to settle down in a career at the Court. Just a few moments later, he meets Leonard Anquetil again, who informs him that he is going to marry Sebastian’s independent sister Viola, to whom the adventurer regularly wrote letters in the last years, and repeats his offer to join him on an expedition. Stunned by this possibility Sebastian agrees to accompany him.

Main characters

- Sebastian / Duke of Chevron: age 19, attractive, heir of Chevron

- Viola: Sebastian's younger sister, independent, critical, breaks through expected conventions

- Lucy / Dowager Duchess of Chevron: Sebastian's and Viola's mother, widow, follows the conventions of the aristocratic society

- Sylvia, Lady Roehampton: notable aristocratic woman, Sebastian's first love affair, friend of the Duchess of Chevron

- Leonard Anquetil: self-made man, independent, no obligations to society

- Teresa Spedding: middle-class woman, wife of a doctor, overcomes the temptation to have a liaison with Sebastian, impressed by Chevron and the aristocratic society

Major themes

- Sackville-West gives insight into the everyday life of the era's aristocracy. She describes the glamorous weekend parties, the numerous weekday luncheons, and other customs and leisure activities, such as card parties. She reveals that the majority of the aristocracy and upper class are superficial, interested in little beyond entertainment; intellectual issues are rarely discussed and then only superficially, and cultural institutions are visited only so one can say one has partaken of the fare. Most of the aristocrats Sackville-West depicts are oblivious to the extensive machinery, in the form of overworked servants, that makes their extravagant, self-indulgent lifestyle possible.

- Chevron, the estate of Sebastian’s family, forms a self-contained world, with shops and a loyal staff that comprises many long-serving families. Sebastian, the heir, values the peaceful atmosphere and the rituals, such as the Christmas tree ceremony. However, Chevron is about to undergo changes: For example, the son of a loyal employee wants to break with family tradition and work in the motor industry. Leonard Anquetil compares Chevron to a “splendid tomb” and states that “the house is dying from the top”.

- Most of the married couples in The Edwardians wed not for love but in order to maintain social standing or wealth; affection and sexual pleasure are found in extramarital affairs, which are common practice but are kept secret — scandals and divorces are to be avoided. (That's why Sylvia Roehampton remains with her husband instead of starting a new life with Sebastian.) Sackville-West also describes a gendered double standard: Men such as Sebastian don't suffer socially for having affairs while they're unmarried, but an unmarried woman even of his privileged class would be ostracized for doing the same.

- Sackville-West also examines whether an individual can follow his or her deepest inclinations, or must adhere to social conventions and family traditions. Leonard Anquetil and Viola choose the former; Anquetil, who isn't bound by aristocratic conventions as is Viola, is able to help emancipate her. Sylvia Roehampton, on the other hand, subordinates personal desires, such as her love for Sebastian, to tradition and the expectations of the aristocracy. Sebastian is torn between those two positions.

Biographical influences

“Vita had done what she set out to do: write a popular success; and she had done it by recreating the lavish, feudal, immoral ancient régime of her childhood. ... Chevron ... is Knole in every detail ... . She promotes the lady of the house to the rank of Duchess, and divides her own personality between the two children of the house – Sebastian, the young heir, dark moody and glamorous, and Viola his withdrawn, straight-haired, sceptical sister. ‘No character in this book is wholly fictitious,’ she wrote provocatively in her Author’s Note.”[2]

Her writing of The Edwardians was greatly affected by Virginia Woolf, Vita’s female lover who introduced her to the Bloomsbury culture. Through her own novel Orlando, the protagonist of which is wholly based on Vita, she inspired her to write a novel about Knole House and her childhood experiences there herself.

Her parents, Lionel Edward Sackville-West, 3rd Baron Sackville and Victoria Sackville-West, had great influence on the development of Vita’s personality. As their only child she had to replace the male heir for her father who introduced her to the duties of a squire and whose love for Knole House, representing to her permanence and security, she adopted. However she could never inherit it because of her sex. Therefore in The Edwardians Knole revives in Chevron as well in its physical features as also in the customs cultivated there. The relationship towards her mother was torn between hatred and love, the last overweighing. Vita was not to dwarf her own beauty or question her value system. Therefore Vita tended to suppress her feminine side and adopt traits of masculine courting behaviour. Lady Sackville-West was a major model for the aristocratic ladies in The Edwardians, where Vita also dealt with the mother-daughter relationship of the Edwardian age.

Vita’s personality was embossed by dualities. Those can be seen in her relationships, her conception of gender, and herself being torn between conformity to traditions and genetic inheritance and her wish for self-determination. This is mirrored in the characters of Sebastian and Viola in The Edwardians.

Critical reception

In general, the book received positive reviews and sold well: 30,000 copies were sold in the first six months in England, and 80,000 copies in the first year in the United States.

Review highlights

See references.[3]

Positive:

- Clear picture of pre-war fashionable English society

- Brilliant comedy of manners

- Vivid atmosphere

- Good integration of “real people” + celebrities

Negative:

- Autobiographical facts → Artistic reality not convincing enough: Sebastian + Leonard Anquetil not as “artistically [...] alive” as the Duchess of Chevron, Viola, Lady Roehampton, Theresa and her husband, the servants + Lord Roehampton’s discovery of the intrigue

- Exaggeration in depiction of English aristocracy → Edwardian elite painted too “black”

- Has “overstepped the limits of fair comment [in the depiction of] ... the follies and falsities of the old regime”

The 2016 edition by Vintage Classics contains an introduction by Kate Williams which is marred by editing errors such as a confusion of the dowager duchess Lucy with Romola Cheyne.

Further reading

- Alden, Patricia. Social Mobility in the English Bildungsroman: Gissing, Hardy, Bennett, and Lawrence. Ann Arbor Michigan: UMI Research Press, 1986.

- Caws, Mary Ann. Vita Sackville-West: Selected Writings, New York: Palgrave, 2002.

- De Salvo, Louise et al. The Letters of Vita Sackville, London: Hutchinson, 1984.

- Glendinning, Victoria. Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1984.

- Glendinning, Victoria. “Introduction”. In Vita Sackville-West: The Edwardians. London: Virago, 2003. vii–xvi.

- Hortmann, Rita. “Nachwort”. In Vita Sackville-West: Pepita: Die Tänzerin und die Lady. Frankfurt/M: Ullstein, 1984. 277–294.

- Leaska, Mitchell. “Introduction”. In Louise De Salvo et al. The Letters of Vita Sackville-West to Virginia Woolf, London: Hutchinson, 1984. 9–46.

- Raitt, Suzanne. The Work and Friendship of V. Sackville-West and Virginia Woolf, Oxford: Clarendon, 1993.

- Stevens, Michael. V. Sackville-West: A Critical Biography. Stockholm: AB Egnellska Boktryckeriet, 1972.

References

- ↑ De Salvo, Louise et al. West to Virginia Woolf, in The Letters of Vita Sackville, London: Hutchinson, 1984.

- ↑ Glendinning, Victoria. Vita: The Life of V. Sackville-West, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1984. p. 231.

- ↑ The Edwardians, Fortnightly Review, 128 (1930:July) p. 141; A. G., The Edwardians, Bookman, 78:466 (1930:July) p. 230; Helm, W. H., The Edwardians, English Review, (1930:July) p. 152

External links

- The Edwardians at Faded Page (Canada)