.jpg.webp) First edition cover | |

| Author | Leon M. Lederman, with Dick Teresi |

|---|---|

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Subject | Physics |

| Publisher | Dell Publishing |

Publication date | 1993 |

| Media type | Print (Hardback & Paperback) |

| ISBN | 0-385-31211-3 (Original hardcover) |

The God Particle: If the Universe Is the Answer, What Is the Question? is a 1993 popular science book by Nobel Prize-winning physicist Leon M. Lederman and science writer Dick Teresi.

The book provides a brief history of particle physics, starting with the pre-Socratic Greek philosopher Democritus, and continuing through Isaac Newton, Roger J. Boscovich, Michael Faraday, and Ernest Rutherford and quantum physics in the 20th century.[1][2][3][4]

Lederman explains in the book why he gave the Higgs boson the nickname "The God Particle":

This boson is so central to the state of physics today, so crucial to our final understanding of the structure of matter, yet so elusive, that I have given it a nickname: the God Particle. Why God Particle? Two reasons. One, the publisher wouldn't let us call it the Goddamn Particle, though that might be a more appropriate title, given its villainous nature and the expense it is causing. And two, there is a connection, of sorts, to another book, a much older one...

— p. 22[5]

In 2013, subsequent to the discovery of the Higgs boson, Lederman co-authored, with theoretical physicist Christopher T. Hill, a sequel: Beyond the God Particle which delves into the future of particle physics in the post-Higgs boson era. This book is part of a trilogy, with companions, Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe and Quantum Physics for Poets (see bibliography below).

Historical context

Fermilab director and subsequent Nobel physics prize winner Leon Lederman was a very prominent early supporter – some sources say the architect[6] or proposer[7] – of the Superconducting Super Collider project, which was endorsed around 1983, and was a major proponent and advocate throughout its lifetime.[8][9] Lederman wrote his 1993 popular science book – which sought to promote awareness of the significance of such a project – in the context of the project's last years and the changing political climate of the 1990s.[10] The increasingly moribund project was finally shelved that same year after some $2 billion of expenditure.[6] The proximate causes of the closure were the rising US budget deficit, rising projected costs of the project, and the cessation of the Cold War, which reduced the perceived political pressure within the United States to undertake and complete high-profile science megaprojects.

List of chapters

- Chapter 1: The Invisible Soccer Ball: This chapter uses a metaphor of a soccer game with an invisible ball to depict the process by which the existence of particles are deduced.[11] Also, in this chapter Dr. Lederman gives a brief background story of what led him to particle physics.[12]

- Chapter 2: The First Particle Physicist: In a fictional dream, Dr. Lederman meets Democritus, an ancient Greek philosopher who lived during the Classical Greek Civilization, and has a conversation (a Socratic dialogue) with him.[13]

- Chapter 3: Looking For The Atom: The Mechanics: This chapter covers Galileo, Tycho Brahe, Johannes Kepler and Isaac Newton.[14]

- Chapter 4: Still Looking for the Atom: Chemists and Electricians: This chapter covers physicists from the 18th century onward including J.J. Thomson, John Dalton, and Dmitri Mendeleev (1834–1907).[15]

- Chapter 5: The Naked Atom: This chapter paints a picture of the shift from classical physics to the birth and development of quantum mechanics.[16]

- Chapter 6: Accelerators: They Smash Atoms, Don’t They?: Covers the development of particle accelerators.[17]

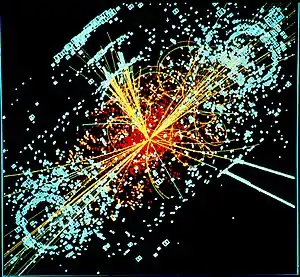

- Chapter 7: A-tom!: The book uses the word "A-tom" to refer to Democritus' fundamental, uncuttable particle. This chapter covers the discovery of the fundamental particles of the Standard Model.[18]

- Chapter 8: The God Particle At Last: Covers spontaneous symmetry breaking and the Higgs boson.[19]

- Chapter 9: Inner Space, Outer Space, and the Time Before Time: Looks at astrophysics and describes the evidence for the Big Bang.[20]

See also

References

- ↑ Higgs, Peter (1964). "Broken Symmetries and the Masses of Gauge Bosons". Physical Review Letters. 13 (16): 508–509. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..508H. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.508.

- ↑ Guralnik, G.; Hagen, C.; Kibble, T. (1964). "Global Conservation Laws and Massless Particles". Physical Review Letters. 13 (20): 585. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..585G. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.585.

- ↑ Englert, F.; Brout, R. (1964). "Broken Symmetry and the Mass of Gauge Vector Mesons". Physical Review Letters. 13 (9): 321. Bibcode:1964PhRvL..13..321E. doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.13.321.

- ↑ James Randerson (30 June 2008). "Father of the 'God Particle'". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 July 2008.

- ↑ L&T p. 22.

- 1 2 Aschenbach, Joy (5 December 1993). "No Resurrection in Sight for Moribund Super Collider: Science: Global financial partnerships could be the only way to salvage such a project. But some feel that Congress delivered a fatal blow". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 16 February 2013. Retrieved 28 December 2020.

Disappointed American physicists are anxiously searching for a way to salvage some science from the ill-fated superconducting super collider ... "We have to keep the momentum and optimism and start thinking about international collaboration," said Leon M. Lederman, the Nobel Prize-winning physicist who was the architect of the super collider plan

{{cite news}}: CS1 maint: unfit URL (link) - ↑ Lillian Hoddeson (Professor of History at the University of Illinois) and Adrienne Kolb (Fermilab archivist and author) (2004). "Vision to reality: From Robert R. Wilson's frontier to Leon M. Lederman's Fermilab". Physics in Perspective. 5 (1): 67–86. arXiv:1110.0486. Bibcode:2003PhP.....5...67H. doi:10.1007/s000160300003. S2CID 118321614.

Lederman also planned what he saw as Fermilab's next machine, the Superconducting SuperCollider (SSC).

{{cite journal}}:|author=has generic name (help) - ↑ Abbott, Charles (June 1987). "Super competition for superconducting super collider". Illinois Issues. p. 18. Retrieved 16 January 2013.

Lederman, who considers himself an unofficial propagandist for the super collider, said the SSC could reverse the physics brain drain in which bright young physicists have left America to work in Europe and elsewhere.

- ↑ Kevles, Daniel J. (Winter 1995). "Good-bye to the SSC: On the Life and Death of the Superconducting Super Collider" (PDF). Caltech Engineering & Science. 58 (2): 16–25. Retrieved 1 May 2013.

Lederman, one of the principal spokesmen for the SSC, was an accomplished high-energy experimentalist who had made Nobel Prize-winning contributions to the development of the Standard Model during the 1960s (although the prize itself did not come until 1988). He was a fixture at congressional hearings on the collider, an unbridled advocate of its merits [...].

(permalink) - ↑ Calder, Nigel (2005). Magic Universe: A Grand Tour of Modern Science. pp. +Leon+lederman, +advertised+the+Higgs+as+The+God+Particle+in+the+title+of+a+book+published+in+1993.%22 369–370. ISBN 9780191622359.

The possibility that the next big machine would create the Higgs became a carrot to dangle in front of funding agencies and politicians. [...] A prominent American physicist, Leon Lederman, advertised the Higgs as The God Particle in the title of a book published in 1993 ... Lederman was involved in a campaign to persuade the US government to continue funding the Superconducting Super Collider... the ink was not dry on Lederman's book before the US Congress decided to write off the billions of dollars already spent.

- ↑ L&T pp. 9–12.

- ↑ L&T pp. 5–8, 21.

- ↑ L&T pp. 32–58.

- ↑ L&T pp. 65–103.

- ↑ L&T pp. 104–140.

- ↑ L&T pp. 141–188.

- ↑ L&T pp. 199–255.

- ↑ L&T pp. 274–341.

- ↑ L&T pp. 342–346.

- ↑ L&T pp. 382–409.

Bibliography

- L&T = Leon M. Lederman and Dick Teresi (2006) [1993]. The God Particle: If the Universe is the Answer, What is the Question?. Boston: Houghton Mifflin Company. ISBN 978-0-61871-168-0.

- Symmetry and the Beautiful Universe, Christopher T. Hill and Leon M. Lederman, Prometheus Books (2005)

- Quantum Physics for Poets, Christopher T. Hill and Leon M. Lederman, Prometheus Books (2010)

- Beyond the God Particle, Christopher T. Hill and Leon M. Lederman, Prometheus Books (2013)