| The Pawnbroker | |

|---|---|

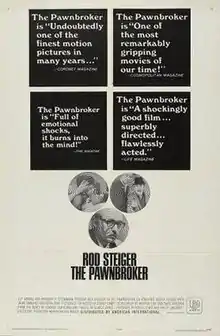

Theatrical release poster | |

| Directed by | Sidney Lumet |

| Written by | Morton S. Fine David Friedkin |

| Based on | The Pawnbroker by Edward Lewis Wallant |

| Produced by | Philip Langner Roger Lewis Ely Landau |

| Starring | Rod Steiger Geraldine Fitzgerald Brock Peters Jaime Sánchez Thelma Oliver |

| Cinematography | Boris Kaufman |

| Edited by | Ralph Rosenblum |

| Music by | Quincy Jones |

Production company | |

| Distributed by | American International Pictures |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 116 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $930,000 |

| Box office | $2.5 million (US rentals),[1] over $4 million global[2] |

The Pawnbroker is a 1964 American drama film directed by Sidney Lumet, starring Rod Steiger, Geraldine Fitzgerald, Brock Peters, Jaime Sánchez and Morgan Freeman in his feature film debut. The screenplay was an adaptation by Morton S. Fine and David Friedkin from the novel of the same name by Edward Lewis Wallant.

The film was the first produced entirely in the United States to deal with the Holocaust from the viewpoint of a survivor.[3] It earned international acclaim for Steiger, launching his career as an A-list actor.[4] It was among the first American films to feature a homosexual character and nudity during the Production Code, and was the first film featuring bare breasts to receive Production Code approval. Although it was publicly announced to be a special exception, the controversy proved to be first of similar major challenges to the Code that ultimately led to its abrogation.[5]

In 2008, The Pawnbroker was selected for preservation in the United States National Film Registry by the Library of Congress as being "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant".[6][7]

Plot

In Nazi Germany, Sol Nazerman, a German-Jewish university professor, is sent to a concentration camp along with his family. He witnesses his two children die and his wife raped by Nazi officers before she is killed.

Twenty-five years later, Nazerman is haunted by his memories. He operates a pawnshop in an East Harlem slum while living in an anonymous Long Island housing tract with his sister-in-law, who is also a Holocaust survivor, and her husband. Numbed and alienated by his experiences, he has trained himself not to show emotion. He describes himself as beyond bitter, viewing the poor people around him as "scum" and "rejects." He acts uninterested and cynical towards his desperate customers and gives them much less than their pawned goods are worth.

Nazerman is idolized by Jesus Ortiz, an ambitious young Puerto Rican who lives with his mother and works for Nazerman as his shop assistant. Ortiz's girlfriend is a prostitute who works for Rodriguez, a racketeer who uses the pawnshop as a front. After hours, Nazerman teaches Ortiz about precious metal appraisal and money, the only thing he still values. Ortiz refers to Nazerman as his "teacher" but his attempts at friendship are rebuffed. Nazerman is also pursued by Marilyn Birchfield, a neighborhood social worker who wants to get to know him better, but he keeps her at arm's length.

Ortiz's girlfriend tries to pawn jewelry to help fund his plan to open a shop; she offers her body to Nazerman to make more money, but he rejects her. When she tells him she works for Rodriguez, he realizes that Rodriguez owes much of his wealth to the brothels he owns and runs. Nazerman recalls his wife's degradation in the concentration camp and tells Rodriguez he no longer wants to do business with him. He also tells Ortiz that he means nothing to him. Crushed by the comment, Ortiz arranges for the pawnshop to be robbed by a neighborhood gang led by Tangee. Meanwhile, Rodriguez and a henchman visit the pawnshop, beating and threatening to kill Nazerman when he refuses to cooperate in the money laundering. In his suicidal despair, he tells them to kill him. Rodriguez promises him that he will die sometime but not immediately, as Nazerman would prefer.

During the attempted robbery by Tangee's gang, Nazerman refuses to hand over his money. A member of the gang pulls a gun and, in trying to save Nazerman, Ortiz is shot. The gang flees and Ortiz drags himself out onto the street. Nazerman stumbles out of his shop and silently sobs while Ortiz dies. Ortiz's body is taken away by ambulance and Nazerman goes back inside. He impales his hand on a receipt spike before wandering away from the shop, presumably for the last time.

Cast

- Rod Steiger – Sol Nazerman

- Geraldine Fitzgerald – Marilyn Birchfield

- Brock Peters – Rodriguez

- Jaime Sánchez – Jesus Ortiz

- Thelma Oliver – Ortiz's girl

- Eusebia Cosme - Mrs. Ortiz (Jesus' mother)[8]

- Marketa Kimbrell – Tessie

- Baruch Lumet – Mendel

- Juano Hernández – Mr. Smith

- Linda Geiser – Ruth Nazerman

- Nancy R. Pollock – Bertha

- Raymond St. Jacques – Tangee

- Charles Dierkop – Robinson

- Morgan Freeman – Man on Street (uncredited)[9]

- Tony Lawrence – Cop (uncredited)[10]

Major themes

The Pawnbroker tells the story of a man whose spiritual "death" in the concentration camps causes him to bury himself in the most dismal location that he can find: a slum in upper Manhattan. Lumet told The New York Times in an interview during the filming that, "The irony of the film is that he finds more life here than anywhere. It's outside Harlem, in housing projects, office buildings, even the Long Island suburbs, everywhere we show on the screen—that everything is conformist, sterile, dead."[11]

The film used flashbacks to reveal Nazerman's backstory. According to a review on the Turner Classic Movies website, it has some similarities to two films of Alain Resnais: Night and Fog (1955) and Hiroshima mon Amour (1959). A recent commentator observed that the film "is uniquely American, with its harsh, unforgiving depiction of New York City, all of it brought to vivid life by Boris Kaufman's black and white cinematography and a dynamic cast highlighted by Rod Steiger's searing portrayal of the title role."[4]

New York Times critic Bosley Crowther wrote that Sol Nazerman "is very much a person of today—a survivor of Nazi persecution who has become detached and remote in the modern world—he casts, as it were, the somber shadow of the legendary, ageless Wandering Jew. That is the mythical Judean who taunted Jesus on the way to Calvary and was condemned to roam the world a lonely outcast until Jesus should come again."[12]

Production notes

Development

The film initially was considered for production in London, in order to take advantage of financial incentives then available for filmmakers.[5]

Directors Stanley Kubrick, Karel Reisz and Franco Zeffirelli turned down the project. Kubrick said he thought Steiger was not "all that exciting." Reisz, whose parents were murdered in the Holocaust, said that for "deep, personal" reasons he "could not objectively associate himself with any subject which has a background of concentration camps." Zeffirelli, then a stage director, was anxious to direct a film, but said that The Pawnbroker was "not the kind of subject [he] would wish to direct, certainly not as his first Anglo-American venture."[5]

Casting

Steiger became involved in the project in 1962, a year after the Wallant novel was published, and was involved in an early reworking of the film's script.[5] He received $50,000 for his performance, far lower than his usual rate, because he trusted Lumet, with whom he had worked on television in the series You Are There.[4]

Lumet, who took over the film after Arthur Hiller was fired, initially had misgivings about Steiger being cast in the lead role. He felt that Steiger "was a rather tasteless actor—awfully talented, but completely tasteless in his choices." Lumet preferred James Mason for the role, and the comedian Groucho Marx was among the performers who had wanted to play Nazerman.[5] However, Steiger pleasantly surprised Lumet when he agreed with him during rehearsals on the repression of the character's feelings. Lumet felt that ultimately Steiger "worked out fine."[13]

In a 1999 television interview, Rod Steiger revealed an inspiration he took from an unlikely source of art. Over a quarter of a century after artist Pablo Picasso's 1937 Guernica, the painting inspired emotional artistic depth again when, in 1964, Steiger borrowed the silent anguish of the skyward cry of the suffering female subject, seen at the right of the canvas. The scene in the film was in the last minutes of The Pawnbroker.

Variety considered Brock Peters the first actor to portray a confirmed homosexual character in an American film.[14]

Filming

The film was shot in New York City, mainly on location and with minimal sets, in the fall of 1963.[5] Much of the filming took place on Park Avenue in Harlem, where the pawnbroker shop was set at 1642 Park Avenue, near the intersection of Park Ave. and 116th Street. Scenes were also filmed in Connecticut, Jericho, New York, and Lincoln Center (with both interior and exterior shots of the Lincoln Towers apartments which were new at the time).[11]

Post-production and release

The film premiered in June 1964 at the Berlin International Film Festival, and was released in the United States in April 1965.[15]

Finding a major U.S. distributor for the film proved difficult because of its nudity and grim subject matter.[5] Producer Ely Landau had the same problem in England until it was booked into a London theater where it had an enormously successful run. As a result, Landau arranged a distribution deal with the Rank Organisation, and it opened in the U.S.[4]

Quincy Jones composed the soundtrack for the film, including "Soul Bossa Nova", which was used in a scene at a nightclub. That would later be used as the main theme to the Austin Powers film series.

The film was edited by Ralph Rosenblum, and is extensively discussed in his book When the Shooting Stops, the Cutting Begins: A Film Editor's Story.[16]

Production Code controversy

The film was controversial on initial release for depicting nude scenes in which actresses Linda Geiser and Thelma Oliver fully exposed their breasts. The scene with Oliver, who played a prostitute, was intercut with a flashback to the concentration camp, in which Nazerman is forced to watch his wife (Geiser) and other women raped by Nazi officers. The nudity resulted in a "C" (condemned) rating from the Catholic Legion of Decency.[4][5] The Legion felt "that a condemnation is necessary in order to put a very definite halt to the effort by producers to introduce nudity into American films."[5] The Legion of Decency's stance was opposed by some Catholic groups, and the National Council of Churches gave the film an award for best picture of the year.[13]

The scenes resulted in conflict with the Motion Picture Association of America, which administered the Motion Picture Production Code. The Association initially rejected the scenes showing bare breasts and a sex scene between Sanchez and Oliver, which it described as "unacceptably sex suggestive and lustful." Despite the rejection, Landau arranged for Allied Artists to release the film without the Production Code seal, and New York censors licensed The Pawnbroker without the cuts demanded by Code administrators. On a 6–3 vote, the Motion Picture Association of America granted the film an "exception" conditional on "reduction in the length of the scenes which the Production Code Administration found unapprovable." The exception to the code was granted as a "special and unique case," and was described by The New York Times at the time as "an unprecedented move that will not, however, set a precedent."[13] The requested reductions of nudity were minimal, and the outcome was viewed in the media as a victory for the film's producers.[5]

Critical reaction

The film, and Steiger's performance in particular, was greeted by widespread critical acclaim.[5] Life magazine praised Steiger's "endless versatility." Brendan Gill wrote in The New Yorker: "By a magic more mysterious. . . than his always clever makeup, he manages to convince me at once that he is whoever he pretends to be."[13]

New York Times critic Bosley Crowther called it a "remarkable picture" that was "a dark and haunting drama of a man who has reasonably eschewed a role of involvement and compassion in a brutal and bitter world and has found his life barren and rootless as a consequence. It is further a drama of discovery of the need of man to try to do something for his fellow human sufferers in the troubled world of today." He praised the performances in the film, including the supporting cast.[12]

One negative review came from Pauline Kael, who called it "trite", but said: "You can see the big pushes for powerful effects, yet it isn't negligible. It wrenches audiences, making them fear that they, too, could become like this man. And when events strip off his armor, he doesn't discover a new, warm humanity, he discovers sharper suffering—just what his armor had protected him from. Most of the intensity comes from Steiger's performance."[4]

Some Jewish groups urged a boycott of the film, in the view that its presentation of a Jewish pawnbroker encouraged anti-Semitism. Black groups felt it encouraged racial stereotypes of the inner city residents as pimps, prostitutes or drug addicts.[4]

Awards and nominations

| Award | Category | Nominee(s) | Result | Ref. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Academy Awards | Best Actor | Rod Steiger | Nominated | [17] |

| Berlin International Film Festival | Golden Bear | Sidney Lumet | Nominated | [18] |

| Best Actor | Rod Steiger | Won | ||

| FIPRESCI Award – Honorable Mention | Sidney Lumet | Won | ||

| Bodil Awards | Best Non-European Film | Won | [19] | |

| British Academy Film Awards | Best Foreign Actor | Rod Steiger | Won | [20] [21] |

| United Nations Award | Sidney Lumet | Nominated | ||

| Directors Guild of America Awards | Outstanding Directorial Achievement in Motion Pictures | Nominated | [22] | |

| Golden Globe Awards | Best Actor in a Motion Picture – Drama | Rod Steiger | Nominated | [23] |

| Laurel Awards | Top Drama | 4th Place | ||

| Top Male Dramatic Performance | Rod Steiger | Nominated | ||

| National Film Preservation Board | National Film Registry | Inducted | [24] | |

| New York Film Critics Circle Awards | Best Film | Nominated | [25] | |

| Best Actor | Rod Steiger | Nominated | ||

| Writers Guild of America Awards | Best Written American Drama | Morton S. Fine and David Friedkin | Won | [26] |

Legacy

The film has become known as the first major American film that even tried to recreate the horrors of the camps of the Jewish Holocaust. A New York Times review of a 2005 documentary on Hollywood's treatment of the Holocaust, Imaginary Witness, said that scenes of the camps in the film as shown in the documentary were "surprisingly mild."[3]

It has been described as "the first stubbornly 'Jewish' film about the Holocaust", and as the foundation for the miniseries Holocaust (1978) and the film Schindler's List (1993).[4][5]

Rod Steiger called The Pawnbroker his favorite film, "by a long shot," in his last television interview on a 2002 episode of Dinner for Five, hosted by actor/director Jon Favreau.[27][28]

Its display of nudity, despite Production Code prohibitions on the practice at the time, is also viewed as a landmark in motion pictures. The Pawnbroker was the first film featuring bare breasts to receive Production Code approval. In his 2008 study of films during that era, Pictures at a Revolution, author Mark Harris wrote that the MPAA's action was "the first of a series of injuries to the Production Code that would prove fatal within three years."[13] The Code was abolished in 1968 in favor of a voluntary ratings system.[5]

Gallery

Musical score and soundtrack

| The Pawnbroker | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

.jpg.webp) | ||||

| Soundtrack album by | ||||

| Released | June 1965 | |||

| Recorded | February 20, 1965 | |||

| Genre | Film score | |||

| Length | 35:45 | |||

| Label | Mercury MG 21011/SR 61011 | |||

| Producer | Quincy Jones | |||

| Quincy Jones chronology | ||||

| ||||

| Review scores | |

|---|---|

| Source | Rating |

| Allmusic | |

The film score was composed, arranged and conducted by Quincy Jones, and the soundtrack album was released on the Mercury label in 1965.[30][31] Initially, Lumet planned to hire John Lewis, the musical director of the Modern Jazz Quartet. Rosenblum, the film's editor, complained to Lumet that Lewis' music was "too cerebral" and suggested Jones instead—a suggestion Lumet accepted.[16]

Reception

Allmusic's Stephen Cook noted "This soundtrack to Sidney Lumet's 1964 film The Pawnbroker might not rate with such other Quincy Jones celluloid efforts as In the Heat of the Night, but its fine mix of jazz, bossa nova, soul, and vocals still makes it one of his best. The Pawnbroker is a must for both Jones fans and film music buffs".[29]

Track listing

All compositions by Quincy Jones

- "Theme from The Pawnbroker" (Lyrics by Jack Lawrence) − 3:07

- "Main Title" − 3:42

- "Harlem Drive" − 1:56

- "The Naked Truth" − 4:08

- "Ortiz' Night Off" − 5:00

- "Theme from The Pawnbroker (Instrumental Version)" − 4:07

- "How Come, You People!" − 2:57

- "Rack 'Em Up" − 2:40

- "Death Scene" − 5:04

- "End Title" − 3:04

- "Theme from the Pawnbroker" − 2:38 Additional track on CD reissue

Personnel

- Orchestra arranged and conducted by Quincy Jones featuring:[32]

- Freddie Hubbard, Bill Berry, trumpets

- J.J. Johnson, trombone

- Anthony Ortega, soprano sax; Oliver Nelson, alto sax, tenor sax; Jerry Dodgion, alto sax

- Toots Thielemans, harmonica

- Bobby Scott,piano, tracks 1-10

- Don Elliott, vibraphone

- Dave Grusin, piano

- Dennis Budimir, guitar

- Carol Kaye, electric bass

- Tony Williams, Bob Cranshaw, Art Davis, acoustic double bass

- Elvin Jones, drums

- Ed Shaughnessy, percussion

- The Don Elliott Voices, vocal.[33]

- Marc Allen (track 1)

- Sarah Vaughan (track 11) − vocals

- Rod Steiger - dialogue (track 7)

See also

References

- ↑ This figure consists of anticipated rentals accruing distributors in North America. See "Top Grossers of 1965", Variety, January 5, 1966 p 36

- ↑ Leff, Leonard J. (1996). "Hollywood and the Holocaust: Remembering The Pawnbroker" (PDF). American Jewish History. 84 (4): 353–376. doi:10.1353/ajh.1996.0045. S2CID 161454898. Retrieved September 14, 2018. See page 11 of PDF.

- 1 2 Gates, Anita (April 5, 2005). "Imaginary Witness: Hollywood and The Holocaust". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 Stafford, Jeff. "The Pawnbroker: Overview Article". TCM.com. Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Leff, Leonard J. (1996). "Hollywood and the Holocaust: Remembering The Pawnbroker" (PDF). American Jewish History. 84 (4): 353–376. doi:10.1353/ajh.1996.0045. S2CID 161454898. Retrieved March 9, 2009.

- ↑ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ↑ "Cinematic Classics, Legendary Stars, Comedic Legends and Novice Filmmakers Showcase the 2008 Film Registry". Library of Congress. Retrieved May 7, 2020.

- ↑ Lopez, Antonio (2012). Unbecoming Blackness: The Diaspora Cultures of Afro-Cuban America. New York, New York: New York University Press. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-8147-6549-4.

- ↑ "A major talent, for heaven and earth". Baltimore Sun. September 28, 2007. Retrieved November 29, 2023.

- ↑ Herbstman, Mandel (April 16, 1965). "Review of New Film: 'The Pawnbroker'". The Film Daily: 3.

- 1 2 Archer, Eugene (November 3, 1963). "As Crowds Watch, 'The Pawnbroker' Goes Into Business in Spanish Harlem". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- 1 2 Crowther, Bosley (April 21, 1965). "The Pawnbroker". The New York Times. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Harris, Mark (2008). Pictures at a Revolution: Five Movies and the Birth of the New Hollywood. Penguin Group. pp. 173–176. ISBN 978-1-59420-152-3.

- ↑ Byron, Stuart (August 9, 1967). "Homo Theme 'Breakthrough'". Variety. p. 7.

- ↑ "Release Dates for The Pawnbroker". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved March 8, 2009.

- 1 2 Rosenblum, Ralph; Karen, Robert (1979). When the Shooting Stops, the Cutting Begins: A Film Editor's Story. New York: Viking Adult. ISBN 978-0-670-75991-0.

- ↑ "The 38th Academy Awards (1966) Nominees and Winners". oscars.org. Retrieved September 4, 2011.

- ↑ "Berlinale 1964: Prize Winners". berlinale.de. Retrieved February 20, 2010.

- ↑ "1966". Bodilprisen (in Danish). October 19, 2015. Retrieved June 29, 2021.

- ↑ "BAFTA Awards: Film in 1967". BAFTA. 1966. Retrieved September 16, 2016.

- ↑ Severo, Richard (July 10, 2002). "Rod Steiger, Oscar-Winning Character Actor, Dies at 77". The New York Times. Archived from the original on September 10, 2014. Retrieved March 10, 2009.

- ↑ "18th DGA Awards". Directors Guild of America Awards. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "The Pawnbroker – Golden Globes". HFPA. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Complete National Film Registry Listing". Library of Congress. Retrieved December 16, 2015.

- ↑ "1965 New York Film Critics Circle Awards". New York Film Critics Circle. Retrieved July 5, 2021.

- ↑ "Awards Winners". Writers Guild of America. Archived from the original on December 5, 2012. Retrieved June 6, 2010.

- ↑ Levesque, John. "IFC's chat show 'Dinner for Five' worth booking -- with reservations". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 25, 2018.

- ↑ "Dinner For Five S01E04 - Ron Livingston, Kevin Pollak, Sarah Silverman, Rod Steiger". YouTube. July 16, 2012. Archived from the original on February 26, 2013.

- 1 2 Cook, Stephen. The Pawnbroker (Original Motion Picture Score) – Review at AllMusic. Retrieved January 17, 2018.

- ↑ Soundtrack Collector: album entry accessed January 17, 2018

- ↑ Mercury 20000 Series B (61000-61099) discography, accessed January 17, 2018

- ↑ "The Pawnbroker". Library of Congress.

- ↑ "The Pawnbroker". Library of Congress. Retrieved August 23, 2018. (from Meeker, David Jazz on Screen)

External links

- The Pawnbroker essay by Annette Insdorf on the National Film Registry website

- The Pawnbroker at IMDb

- The Pawnbroker at the TCM Movie Database

- The Pawnbroker at AllMovie

- The Pawnbroker at Rotten Tomatoes

- The Representation of Trauma and Memory in The Pawnbroker by Peter Wilshire

- The Pawnbroker essay by Daniel Eagan in America's Film Legacy: The Authoritative Guide to the Landmark Movies in the National Film Registry, A&C Black, 2010 ISBN 0826429777, pages 611-613