Theodore Wells Pietsch II (September 23, 1912, in Baltimore, Maryland ‒ August 24, 1993, in Everett, Washington) was an American automobile stylist and industrial designer who, with little formal education, managed to launch a career in automobile design that took him over a period of 38 years to nearly every major automobile company in the nation.

Theodore Wells Pietsch | |

|---|---|

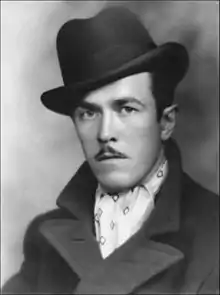

Theodore Wells Pietsch II, 1935 | |

| Born | September 23, 1912 Baltimore, Maryland |

| Died | August 24, 1993 Everett, Washington |

| Nationality | American |

| Occupation(s) | Automobile stylist and industrial designer |

Formative Years: 1912–1934

From an early age, Theodore W. Pietsch showed a strong fascination for cars, reflecting a wide family interest in automobiles and the automotive industry.[1] In the teens and 20s, before the stock-market crash of 1929 took most of it away, the family was quite well-off, able to afford "big Packards" driven by a full-time chauffeur. While his father, Theodore Wells Pietsch I (1869−1930), a well-known Baltimore architect, never learned to drive, his mother, Gertrude Carroll Zell (1888−1968), knew cars very well—she is said to have been the first woman to drive a car in Maryland. One of his uncles, Arthur Stanley Zell (1880−1935), was a pioneer Maryland automobile dealer and sportsman who as president of the Zell Motor Car Company and of Stanley Zell, Inc., was the first automobile distributor in Maryland.[2][3][4][5][6]

Pietsch attended the Stuyvesant School for Boys in Warrenton, Virginia, and later, from 1930 to 1933, the Maryland Institute, Baltimore, where he majored in design and mechanical drawing. By his mid-teens, he was creating original designs of his own in the flat, two-dimensional style of car catalogs of the time. It was the originality and style of these early drawings that would later get the attention of prospective employers.[1]

Chrysler Corporation, Ken Lee, and the Star Car: 1934–1940

In late 1934, Pietsch left Baltimore for Detroit where he began his career under Ken Lee as a junior draftsman for the Chrysler Corporation, serving initially as an apprentice but eventually working up to duties equivalent to those of a "senior designer." His first major assignment was head designer of what was then called simply the "Ken Lee Research Car," an experimental small car that later became known as the "Star Car."[7] The uncanny resemblance of this car to the German Volkswagen led to speculation that Pietsch's design was copied by Ferdinand Porsche who had been instructed by Hitler to produce the "People's Car" and who most probably saw the "Star Car" during one or both of his visits to Detroit in 1936.[1][8]

Hudson Motor Car Company and War Work: 1940–1944

In 1940, Pietsch left Chrysler for the position of Senior Designer at the Hudson Motor Car Company, where he worked primarily at the drawing board making "quick-idea" sketches, color renderings in a variety of media (including catalog-quality air-brush work), accurate scale and full-size layouts, and rough sketching in three-dimensional clay models. At Hudson Motor he was also assigned to war work that consisted of making accurate perspective drawings of airplane assemblies and subassemblies from blueprints, and air-brush retouching of photographs (that were later used in an instruction manual prepared for the armed services) of mechanical parts of an anti-aircraft gun.[9] It would be projects like this, but in particular the years spent interpreting the blueprints for the B-29, that protected him against the draft and provided military deferment throughout the war.[1]

Briggs Manufacturing Company and the Packard Clipper: 1944–1947

In autumn 1944, Pietsch left Hudson to work for Briggs Manufacturing Company, a company founded in 1908 by Walter Owen Briggs (1877–1952) that became the world's largest independent producer of automobile bodies. During the war, the company was a major supplier for the U.S. military, producing over a billion dollars worth of steel and aluminum products. In 1944, a record workforce of some 31,000 men and women built a wide variety of items, including aircraft gun turrets, wings, stabilizers, ailerons, tank hulls, bomb and wheel doors for the B-29, to mention only a few.[10] But by September 1944, when Pietsch signed on, they were already looking ahead to post-war car designs, and efforts were underway to secure contracts for automotive bodies from Packard and Chrysler, among other companies.[10] Early styling projects assigned to Pietsch included work on the Packard Clipper as well as some formal limousines on Chrysler chassis, and "special sedans," some designed specifically for Walter P. Chrysler and others for W. O. Briggs himself, none of which were ever built.

Ford Motor Car Company: 1947–1950

As he had done at Hudson and Briggs in previous years, Pietsch made an appointment to discuss job possibilities at yet another firm, this time the Ford Motor Car Company. In October 1947, with samples of his work in tow, he interviewed successfully and by mid-November of that year, he was working at Ford as the new assistant head of styling in the Ford studio, working initially in exteriors under the supervision of Adrian Gil Spear. For most U.S. automobile companies, designs for the first two or three postwar years were not much more than facelifts of 1941 and 1942 models. This was certainly true for Ford—efforts in 1946 were nearly all directed toward the first all-new model, which turned out to be the highly successful 1949 Ford.[11][12] Pietsch arrived too late to participate in the excitement of that period—work on the prototype for the '49 had just been completed, and this meant that much of the exterior work assigned to him was looking ahead to 1950 and beyond.

Back to Chrysler, Virgil Exner, and the Dream Cars of Ghia: 1950–1952

Pietsch went back to Chrysler in 1950, this time to work for Virgil Max Exner (1909−1973), one of the most celebrated personalities in automotive design and who, a year earlier, had taken over Chrysler's Advanced Styling Group. Exner had the salesmanship and persuasiveness required to make badly needed changes that would by the mid-1950s bring Chrysler to the forefront of American automobile design.[1][13] Now as Director of Styling, Exner set about rebuilding the department, turning it into the talk of the town, not only among Detroit's styling circles but of the entire country. Pietsch played a decisive role in this domestic success as well as in Chrysler's association with Italian auto makers—first, a short-lived relationship with Pinin Farina in 1950, and then, in the following year, with Carrozzeria Ghia of Turin.[14] By 1953, a half a dozen Italian-built Chrysler show-cars had been created. Under these ideal working conditions, it's a wonder that Pietsch didn't stay longer with Exner—the potential at Chrysler for new and exciting things was enormous, but once again the thrill of a new challenge was too great. Responding in early 1952 to an attractive offer from Raymond Loewy, brokered in part by his old friend Bob Koto, he moved from Detroit to South Bend, Indiana, to join Raymond Loewy and Associates, which at the time held the Studebaker design contract.

Raymond Loewy and Associates and the Studebaker Account: 1952–1955

Raymond Fernand Loewy (1893–1986), perhaps the world's best known industrial designer, established himself in 1934 by designing the first modern, stand-alone refrigerator for Sears, Roebuck and Co., which resulted the following year in huge sales for the company. Shortly thereafter, all kinds of lucrative contracts came his way. By the late 1930s and early 40s, he had sold designs for Greyhound buses, Pensy railcars and locomotives, TWA sleeper planes, Matson ships and large ocean liners, Pepsodent toothpaste tubes, Schick electric shavers, buildings of all kinds, including supermarkets, and hundreds of other products, not the least of which were Studebakers.[15][16][17]

Working for Raymond Loewy and Associates, which at that time was responsible for all Studebaker styling, was a unique experience. There were no individual studios set up with all sorts of titles for the designers, just several large rooms located in the old Chippewa Avenue truck plant in South Bend where Studebaker had manufactured its aircraft engines and army trucks during the war. The designers had just one boss, Bob Bourke, and his assistant, Bob Koto, and everyone, including Bourke and Koto, wore many hats. They sketched, and modeled in clay; in fact, the emphasis was on modeling. They often worked into the small hours of the morning with no overtime pay. The clay work was new to Pietsch and by his own admission he never became very adept at it because designers in Detroit, where he had received all his prior training, were not involved in modeling. He strongly believed, however, that designers should be skilled at drawing and rendering as well as modeling.

Studebaker had been on the decline since its peak income year in 1949—the failure to understand market conditions, and an inability to appreciate public interest in the better-selling models, which resulted in severe underproduction—were mistakes of managers who seemed to be unable to respond to disappointing sales other than blame Loewy's advanced styling studio. Pietsch remembers management complaining about how European styling ruined Studebaker, but it was, in his opinion, all misplaced condemnation.[18]

Things were so bad by late 1953 that discussion turned to the idea of teaming up with another car company, and by the following June, with sales for 1954 worse than ever, a merger with Packard was approved.[19] The new Studebaker-Packard management decided to sever the expensive relationship with Loewy and Associates, thinking that their own in-house styling team should be given full control of Studebaker design efforts.[20] Thus, in early 1955, the contract with Raymond Loewy, which had existed since 1938, was not renewed, and Pietsch, along with everyone else, was given the option of staying with Loewy or switching over to Studebaker proper. Pietsch decided that the Loewy situation was much too tenuous and, even as shabby as Studebaker was at the time, opted to stay with the sinking ship.

Studebaker-Packard—the End in Sight, and Industrial Design: 1955–1962

It was now mid-1955, Studebaker had fully merged with Packard, and Loewy and his team of designers were gone—both moves described by Pietsch as "desperate clutching at straws by a dying company."[1] New titles were passed out and Pietsch was named "Manager Studebaker President Exterior Studio," and a year later (1956), "Assistant Head Truck Exterior Studio," in charge of two designers and a clay modeler, assigning and supervising their work in the absence of the studio head, and acting as a liaison between the styling and engineering departments. But despite reorganization and new faces, Studebaker-Packard remained in deep trouble.[21][22] In 1958, the situation was so dire that Pietsch and a number of his fellow designers were laid off. Now, for the first time in his career, Pietsch was unable to immediately step into another automotive design job. After several months looking for work in the South Bend area, he went to Chicago, where he was soon offered a position by the industrial design firm of Dave Chapman, Incorporated. Commuting weekly by train between South Bend and Chicago, he was responsible for the account of a department of Montgomery Ward and Company, which included, among other things, the design of water heaters, water softeners, water pumps, furnaces, air-conditioners, incinerators, and ventilating fans. He also did considerable work on the design of boats, outboard motors, and radios.

Unhappy with the work in Chicago, Pietsch returned to South Bend where he found employment for a few months with another small industrial design firm called Good Design Associates, but then, in late 1959, he got back to cars—this time, with American Motors in Detroit, a job he held for only about a year, quitting abruptly when he was suddenly called back to Studebaker. Randal D. Faurot, newly appointed head of styling, called on Pietsch to help rebuild the department, offering him a position as his assistant that he couldn't refuse. In June 1962, however, frustrated and angry over management's abrupt decision to cancel a project that he had worked for many months—the design for an all-new version of the Studebaker Lark for 1962—Pietsch lost his temper and was fired.[1] It was a tumultuous and abrupt ending to a frustrating, decade-long struggle at Studebaker.

A last Stint at Chrysler, American Motors, and Retirement: 1962–1972

Once again out of work, Pietsch wrote on July 2, 1962, to his old friend Cliff Voss in Detroit, one of "Exner's boys," with whom he had worked at Chrysler back in the early 1950s. Within a few weeks, Pietsch was back for a third and final hitch with the Chrysler Corporation, but these turned out to be unhappy years. Chrysler was by now a completely different place. There was no longer the camaraderie and warm atmosphere that had been there before. The studios were now segregated and the old feeling of team effort, along with most of his old friends, was gone. Styling had become a big well-structured and impersonal organization much like the situation at Ford and General Motors.

Adding to the disappointment, Pietsch was assigned from the start to "interiors," which meant dashboards—sketches and more sketches of instruments and instrument panels, reminiscent of the work that had "bored him to death" back at Ford in the late 1940s. Soon this narrowed down to nothing but "ornamentation," in which he was obliged to spend all his time designing nameplates, lettering, and the configuration of numerals on speedometers, tachometers, and other instruments, all extremely tedious work. But he stuck with it for seven and a half years, exclaiming later that he didn't know how he managed to do it for so long.

In February 1970, Pietsch was caught one last time in one of the many Chrysler lay-offs, but, lucky once again, he got a call a short time later from American Motors, asking if he'd like to go to work for Jeep.[23] But before Pietsch realized it, he was right back where he had been at Chrysler the year before, "doing mostly calibrations of the numerals on dashboard instruments." That his graphics were used without change on the instrument panels of the '72 and '73 Jeep Wagoneer provided little satisfaction. There was nothing about the Jeep line that interested him. Although he did his best every day to appear enthusiastic, Pietsch was so bored at work that he "could hardly see straight," and he worried also that his health was beginning to fail. In February 1972, after only two years with Jeep, he decided to retire.

Personal life

On June 24, 1938, Pietsch married Louise Mary Shamlian (December 1, 1914, Watertown, Massachusetts − January 15, 1987, Seal Beach, California), with whom he had three children: Priscilla Esther Pietsch, born December 22, 1941; Theodore Wells Pietsch III, March 6, 1945; and Louise Jean Pietsch May 11, 1948. His health gradually worsening, he died of congestive heart failure in a nursing home in Everett, Washington, on August 24, 1993, at age 80.

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Pietsch, Theodore W. (2010). Theodore W. Pietsch II (1912−1993) and the Development of Automobile Design in the Golden Age, with foreword by Frederic A. Sharf. Lynn, Massachusetts: Velocity Print Solutions.

- ↑ Baltimore Herald. December 10, 1905.

- ↑ Baltimore Herald. January 7, 1906.

- ↑ Seal, Rector, R. (1985). Maryland Automobile History, 1900-1942. Chicago: Adams Press. pp. 105–109.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ↑ Baltimore Herald. November 27, 1905.

- ↑ Baltimore Herald. April 7, 1906.

- ↑ Lamm, Michael (1972). "MoPar's star cars: were these two fwd, 5-cyl. experimentals Chrysler's answer to GM's X-Cars?". Special Interest Autos. 10: 16–21.

- ↑ Curio, Vincent (2000). Chrysler: The Life and Times of an Automotive Genius. Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 521, 556.

- ↑ Koto, Holden N. (1976). "Living with style by Holden Koto, as told to Michael Lamm". Special Interest Autos. 32: 40.

- 1 2 Lamm, Michael (1973). "Body by Briggs". Special Interest Autos. 19: 29.

- ↑ Bridges, John (1984). Bob Bourke Designs for Studebaker. Nashville, Tennessee: J. B. Enterprises. pp. 64–67.

- ↑ Stephenson, Mary (1993). "Richard Caleal: automotive designer". Collectible Automobile. 10: 70–75.

- ↑ Godshall, Jeff (1975). "The last DeSoto: Styling by Virgil Exner". Special Interest Autos. 26: 14.

- ↑ Langworth, Richard M. (1975). "Thinking ahead: Ghia-Chrysler showcars". Special Interest Autos. 30: 18.

- ↑ Lamm, Michael (1971). "Before the new wore off: What the "Stude Graveyard" cars looked like when new". Special Interest Autos. 6: 13.

- ↑ Reese, Elizabeth (1990). Raymond Loewy: Pioneer of American Industrial Design. Munich, Germany: Prestel-Verlag. pp. 39–41.

- ↑ "Up from the Egg". Time Magazine. 54 (18): 68–74. October 31, 1949.

- ↑ Langworth, Richard M. (1993). Studebaker 1946–1966: The Classic Postwar Years. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers and Wholesalers. pp. 165.

- ↑ Langworth, Richard M. (1993). Studebaker 1946–1966: The Classic Postwar Years. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers and Wholesalers. pp. 72.

- ↑ Langworth, Richard M. (1993). Studebaker 1946–1966: The Classic Postwar Years. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers and Wholesalers. pp. 81.

- ↑ Langworth, Richard M. (1993). Studebaker 1946–1966: The Classic Postwar Years. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers and Wholesalers. pp. 102.

- ↑ Langworth, Richard M. (1993). Studebaker 1946–1966: The Classic Postwar Years. Osceola, Wisconsin: Motorbooks International Publishers and Wholesalers. pp. 131, 141.

- ↑ Foster, P.R. (2004). The Story of Jeep, 2nd edition. Lola, Wisconsin: Krause Publications. p. 132.