Thermoporometry and cryoporometry are methods for measuring porosity and pore-size distributions. A small region of solid melts at a lower temperature than the bulk solid, as given by the Gibbs–Thomson equation. Thus, if a liquid is imbibed into a porous material, and then frozen, the melting temperature will provide information on the pore-size distribution. The detection of the melting can be done by sensing the transient heat flows during phase transitions using differential scanning calorimetry – DSC thermoporometry,[1] measuring the quantity of mobile liquid using nuclear magnetic resonance – NMR cryoporometry (NMRC)[2][3] or measuring the amplitude of neutron scattering from the imbibed crystalline or liquid phases – ND cryoporometry (NDC).[4]

To make a thermoporometry / cryoporometry measurement, a liquid is imbibed into the porous sample, the sample cooled until all the liquid is frozen, and then warmed until all the liquid is again melted. Measurements are made of the phase changes or of the quantity of the liquid that is crystalline / liquid (depending on the measurement technique used).

The techniques make use of the Gibbs–Thomson effect: small crystals of a liquid in the pores melt at a lower temperature than the bulk liquid : The melting point depression is inversely proportional to the pore size. The technique is closely related to that of use of gas adsorption to measure pore sizes but uses the Gibbs–Thomson equation rather than the Kelvin equation. They are both particular cases of the Gibbs Equations (Josiah Willard Gibbs): the Kelvin equation is the constant temperature case, and the Gibbs–Thomson equation is the constant pressure case.[2]

Technique variants

DSC Thermoporometry

This technique uses differential scanning calorimetry (DSC) to detect the phase changes. The signal detection relies on transient heat flows of latent heat of fusion at the phase changes, and thus the measurement can not be made arbitrarily slowly, limiting the resolution in pore size. There are also difficulties in obtaining measurements of pore volume.[1]

Nuclear magnetic resonance cryoporometry

NMRC is a recent technique (originated in 1993) for measuring total porosity and pore size distributions. It makes use of the Gibbs–Thomson effect: small crystals of a liquid in the pores melt at a lower temperature than the bulk liquid : The melting point depression is inversely proportional to the pore size. The technique is closely related to that of use of gas adsorption to measure pore sizes but uses the Gibbs–Thomson equation rather than the Kelvin equation. They are both particular cases of the Gibbs Equations (Josiah Willard Gibbs): the Kelvin equation is the constant temperature case, and the Gibbs–Thomson equation is the constant pressure case.[2][3]

Nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) may be used as a convenient method of measuring the quantity of liquid that has melted, as a function of temperature, making use of the fact that the relaxation time in a frozen material is usually much shorter than that in a mobile liquid. To make the measurement it is common to just measure the amplitude of an NMR echo at a few milliseconds delay, to ensure that all the signal from the solid has decayed. The technique was developed at the University of Kent in the UK, by Prof. John H. Strange.[5]

NMRC is based on two equations, the Gibbs–Thomson equation, that maps the melting point depression to pore size, and the Strange–Rahman–Smith equation[5] that maps the melted signal amplitude at a particular temperature to pore volume.

To make an NMR cryoporometry measurement, a liquid is imbibed into the porous sample, the sample cooled until all the liquid is frozen, and then warmed slowly, while measuring the quantity of the liquid that is liquid.

Thus NMRC cryoporometry is similar to DSC thermoporosimetry, but has higher resolution, as the signal detection does not rely on transient heat flows, and the measurement can be made arbitrarily slowly. Volume calibration of the total porosity and pore-size can be good, just involving ratioing the NMR signal amplitude at a particular pore diameter to the amplitude when all the liquid (of known mass) is melted. NMRC is suitable for measuring pore diameters in the range 1 nm to about 2 µm. Instrumentation to make NMR Cryoporometric measurements is commercially available.[6]

Note: the Gibbs-Thomson equation contains a geometric term relating to the curvature of the ice-liquid interface. This curvature may be different in different pore geometries; thus using a sol-gel calibration (~spheres) gives about a factor of two error when used with SBA-15 (cylindrical pores). Similarly the freezing and melting curvatures (typically spherical on ice intrusion, and cylindrical on ice melting), result in a difference in freezing and melting temperature even in cylindrical pores where there is no "ink-bottle" effect. [7]

It is also possible to adapt the basic NMRC experiment to provide structural resolution in spatially dependent pore size distributions, by combining NMRC with standard Magnetic resonance imaging protocols,[8] or to provide behavioural information about the confined liquid.[9]

Gibbs-Thomson melting point depression for 10 different pore-size sol-gel silicas plotted against measured gas-adsorption diameter.

Gibbs-Thomson melting point depression for 10 different pore-size sol-gel silicas plotted against measured gas-adsorption diameter. NMR Cryoporometric melting curve for an SBA-15 porous silica. This shows a very sharp melting at a Gibbs-Thomson depressed melting point of about 13C, due to the uniform size of the cylindrical pores.

NMR Cryoporometric melting curve for an SBA-15 porous silica. This shows a very sharp melting at a Gibbs-Thomson depressed melting point of about 13C, due to the uniform size of the cylindrical pores. NMR Cryoporometry Pore Size Distribution for an SBA-15 templated. silica, using a Gibbs-Thomson calibration from sol-gel silicas.

NMR Cryoporometry Pore Size Distribution for an SBA-15 templated. silica, using a Gibbs-Thomson calibration from sol-gel silicas. Normalised monomodal silica pore-size distributions, measured by NMR Cryoporometry.

Normalised monomodal silica pore-size distributions, measured by NMR Cryoporometry. A 2D resolved Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Cryoporometry colour map of pore sizes in 4 tubes. A standard NMR imaging protocol is added to a standard NMR cryoporometry protocol, so as to spatially resolve the mesoscale median pore-size on the macroscale, as a 2D colour map.

A 2D resolved Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Cryoporometry colour map of pore sizes in 4 tubes. A standard NMR imaging protocol is added to a standard NMR cryoporometry protocol, so as to spatially resolve the mesoscale median pore-size on the macroscale, as a 2D colour map. Pore-Size Distributions (PSD) for shale, carbonate and sandstone rocks as measured by NMR Cryoporometry (NMRC), measuring each sample twice to demonstrate repeatability. The shale and carbonate were measured using water as a probe liquid, and the sandstone using cyclohexane.

Pore-Size Distributions (PSD) for shale, carbonate and sandstone rocks as measured by NMR Cryoporometry (NMRC), measuring each sample twice to demonstrate repeatability. The shale and carbonate were measured using water as a probe liquid, and the sandstone using cyclohexane.

Neutron diffraction cryoporometry

Modern neutron diffractometers have the capability to measure complete scattering spectra in a couple of minutes, as the temperature is ramped, enabling cryoporometry experiments to be performed.[4]

ND cryoporometry has the unique distinction of being able to monitor as a function of temperature the quantity of different crystalline phases (such as hexagonal ice and cubic ice) as well as the liquid phase, and thus can give pore-phase structural information as a function of temperature.[4]

Pore size measurements using both melting and freezing events

The Gibbs–Thomson effect acts to lower both melting and freezing point, and also to raise boiling point. However, simple cooling of an all-liquid sample usually leads to a state of non-equilibrium super cooling and only eventual non-equilibrium freezing – to obtain a measurement of the equilibrium freezing event, it is necessary to first cool enough to freeze a sample with excess liquid outside the pores, then warm the sample until the liquid in the pores is all melted, but the bulk material is still frozen. Then on re-cooling the equilibrium freezing event can be measured, as the external ice will then grow into the pores. [10] [11] This is in effect an "ice intrusion" measurement (c.f. Mercury Intrusion Porosimetry), and as such in part may provide information on pore throat properties. The melting event was then previously expected to provide more accurate information on the pore body. However, a new melting mechanism has been proposed which means the melting event does not provide accurate information on the pore body.[12] The melting mechanism has been termed advanced melting and is described below.

The advanced melting mechanism [12]

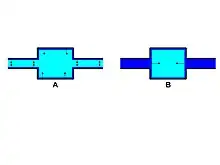

The melting process for the frozen phase is initiated from existing molten phase, such as the liquid-like layer that is retained at the pore wall. This is shown in Figure 1 for a through ink bottle pore model (position A); the arrows show how the liquid-like layer initiates the melting process and this melting mechanism is said to occur via sleeve shaped menisci. For such a melting mechanism, the smaller necks will melt first and as the temperature is raised the large pore will then melt. Therefore, the melting event would give an accurate description of the necks and body.

However, in cylindrical pores, melting would occur at a lower temperature via a hemispherical meniscus (between solid and molten phases), than it would via a sleeve-shaped meniscus. Scanning curves and loops have been used to show that cryoporometry melting curves are prone to pore-pore cooperative effects[12] and this is demonstrated by position B in Figure 1. For the through ink bottle pore, melting is initiated in the outer necks from the thin cylindrical sleeve of permanently unfrozen liquid-like fluid that exists at the pore wall. Once the necks have become molten via the cylindrical sleeve meniscus mechanism, a hemispherical meniscus will be formed at both ends of the larger pore body. The hemispherical menisci can then initiate the melting process in the large pore. Moreover, if the larger pore radius is smaller than the critical size for melting via a hemispherical meniscus at the current temperature, then the larger pore will melt at the same temperature as the smaller pore. Therefore, the melting event will not give accurate information on the pore body. If the incorrect melting mechanism is assumed when deriving a PSD (pore size distribution) there will be at least a 100% error in the PSD. Moreover, it has been shown that advanced melting effects can lead to a dramatic skew towards smaller pores in PSDs for mesoporous sol-gel silicas, determined from cryoporometry melting curves.[12]

Applications

NMR cryoporometry (external cryoporometry website) is a very useful nano- through meso- to micro-metrology technique (nanometrology, nano-science.co.uk/nano-metrology) that has been used to study many materials, and has particularly been used to study porous rocks (i.e. sandstone, shale and chalk/carbonate rocks), with a view to improving oil extraction, shale gas extraction and water abstraction. Also very useful for studying porous building materials such as wood, cement and concrete. A currently exciting application for NMR Cryoporometry is the measurement of porosity and pore-size distributions, in the study of carbon, charcoal and biochar. Biochar is regarded as an important soil enhancer (used since pre-history), and offers great possibilities for carbon dioxide removal from the biosphere.

Materials studied by NMR cryoporometry include:

- Sol-gel & CPG silicas,

- MCM templated silicas,

- SBA templated silicas,

- Activated carbons,

- Zeolites,

- Cement and concrete,

- Fired & unfired clays,

- Marine Sediments,

- Chalks, Shales,

- Sandstones,

- Oil-bearing rocks,

- Meteorites,

- Wood,

- Paper,

- Rubbers,

- Emulsions and paint,

- Artificial skin,

- Bone,

- Melanised fungal cells.

Possible future application include measuring porosity and pore-size distributions in porous medical implants.

References

- 1 2 Brun, M.; Lallemand, A.; Quinson, J-F.; Eyraud, C. (1977), "A new method for the simultaneous determination of the size and the shape of pores: The Thermoporometry", Thermochimica Acta, 21: 59–88, doi:10.1016/0040-6031(77)85122-8

- 1 2 3 Mitchell, J.; Webber, J. Beau W.; Strange, J.H. (2008), "Nuclear Magnetic Resonance Cryoporometry" (PDF), Phys. Rep., 461 (1): 1–36, Bibcode:2008PhR...461....1M, doi:10.1016/j.physrep.2008.02.001

- 1 2 Petrov, Oleg V.; Furo, Istvan (2009), "NMR cryoporometry: Principles applications and potential", Prog. Nucl. Mag. Res. Sp., 54 (2): 97–122, doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2008.06.001

- 1 2 3 Webber, J. Beau W.; Dore, John C. (2008), "Neutron Diffraction Cryoporometry – a measurement technique for studying mesoporous materials and the phases of contained liquids and their crystalline forms" (PDF), Nucl. Instrum. Methods A, 586 (2): 356–366, Bibcode:2008NIMPA.586..356W, doi:10.1016/j.nima.2007.12.004

- 1 2 Strange, J.H.; Rahman, M.; Smith, E.G. (Nov 1993), "Characterization of Porous Solids by NMR", Phys. Rev. Lett., 71 (21): 3589–3591, Bibcode:1993PhRvL..71.3589S, doi:10.1103/PhysRevLett.71.3589, PMID 10055015

- ↑ Webber, J. Beau W.; Liu, Huabing (2023). "The implementation of an easy-to-apply NMR cryoporometric instrument for porous materials". Magnetic Resonance Imaging. 100: 36–42. doi:10.1016/j.mri.2023.03.006. PMID 36924808. S2CID 257569187.

- ↑ Webber, J.B.W. (2010), "Studies of nano-structured liquids in confined geometry and at surfaces" (PDF), Progress in NMR Spectroscopy, 56 (1): 78–93, doi:10.1016/j.pnmrs.2009.09.001, PMID 20633349

- ↑ Strange, J.H.; Webber, J.B.W. (1997), "Spatially resolved pore size distributions by NMR" (PDF), Meas. Sci. Technol., 8 (5): 555–561, Bibcode:1997MeScT...8..555S, doi:10.1088/0957-0233/8/5/015, S2CID 250914608

- ↑ Alnaimi, S.M.; Mitchell, J.; Strange, J.H.; Webber, J.B.W. (2004), "Binary liquid mixtures in porous solids" (PDF), J. Chem. Phys., 120 (5): 2075–2077, Bibcode:2004JChPh.120.2075A, doi:10.1063/1.1643730, PMID 15268344

- ↑ Petrov, O.; Furo, I. (2006), "Curvature-dependent metastability of the solid phase and the freezing-melting hysteresis in pores", Phys. Rev., 73 (1): 7, Bibcode:2006PhRvE..73a1608P, doi:10.1103/physreve.73.011608, PMID 16486162

- ↑ Webber, J. Beau W.; Anderson, Ross; Strange, John H.; Tohidi, Bahman (2007), "Clathrate formation and dissociation in vapour/water/ice/hydrate systems in SBA-15 Sol-Gel and CPG porous media as probed by NMR relaxation novel protocol NMR Cryoporometry Neutron Scattering and ab-initio quantum-mechanical molecular dynamics simulation" (PDF), Magn. Reson. Imaging, 25 (4): 533–536, doi:10.1016/j.mri.2006.11.022, PMID 17466781

- 1 2 3 4 5 Hitchcock, I.; Holt, E. M.; Lowe, J. P.; Rigby, S. P. (2011), "Studies of freezing–melting hysteresis in cryoporometry scanning loop experiments using NMR diffusometry and relaxometry", Chem. Eng. Sci., 66 (4): 582–592, Bibcode:2011ChEnS..66..582H, doi:10.1016/j.ces.2010.10.027