Thomas Lincoln | |

|---|---|

Thomas Lincoln (1778–1851) | |

| Born | January 6, 1778[lower-alpha 1] |

| Died | January 17, 1851 (aged 73) Coles County, Illinois, U.S. |

| Occupation(s) | Farmer, carpenter |

| Spouses | |

| Children | 3, including Sarah and Abraham |

| Parents |

|

| Family | See Lincoln family |

Thomas Lincoln (January 6, 1778[lower-alpha 1] – January 17, 1851) was an American farmer, carpenter, and father of the 16th president of the United States, Abraham Lincoln. Unlike some of his ancestors, Thomas could not write. He struggled to make a successful living for his family and faced difficult challenges in Kentucky real estate boundary and title disputes, the early death of his first wife, and the integration of his second wife's family into his own family, before making his final home in Illinois.

Ancestors

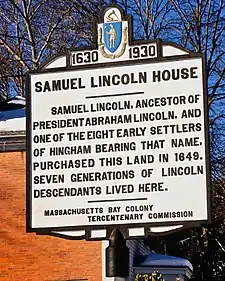

Lincoln was descended from Samuel Lincoln, a respected Puritan weaver, businessman and trader from the County of Norfolk in East Anglia who landed in Hingham in the Massachusetts Bay Colony in 1637.[1][lower-alpha 2] Some Lincolns later migrated into Berks County, Pennsylvania, where they intermarried with Quakers, but did not retain the peculiar ways.[1][3] According to the National Humanities Center, both Quakers and Puritans were opposed to slavery even though many profited from it.[4]

Noteworthy ancestors include Samuel's grandson, Mordecai (1686–1736) who married Hannah Salter from a prominent political family, and made a name for himself in Pennsylvania society as a wealthy landowner and ironmaster.[5] Mordecai and Hannah's son, John Lincoln (1716–1788) settled in Rockingham County, Virginia and built a large, prosperous farm nestled in the Shenandoah Valley.[6]

Abraham Lincoln, instead of being the unique blossom on an otherwise barren family tree, belonged to the seventh American generation of a family with competent means, a reputation for integrity, and a modest record of public service.

John Lincoln gave 210 acres of prime Virginia land to his first son, Captain Abraham Lincoln (1744–1786),[5][7] a veteran of the American Revolutionary War. In 1770, Abraham married Bathsheba Herring (c. 1742–1836), who was born in Rockingham County, Virginia.[5][7] Bathsheba was the daughter of Alexander Herring and wife Abigail Harrison, of the Harrison family of Virginia with Thomas Harrison his maternal great-great-grandfather.[8]

Early life

Virginia

Thomas was born in 1778 in Linville Creek, Virginia, to Abraham and Bethsheba Lincoln.[9]

The Lincolns later sold the land in the 1780s to move to western Virginia, now Springfield, Kentucky.[6][10] He amassed an estate of 5,544 acres of prime Kentucky land, realizing the bounty as advised by Daniel Boone, a relative of the Lincoln family.[6]

In May 1786, Lincoln witnessed the murder of his father by Native Americans "... when he was laboring to open a farm in the forest." Lincoln's life was saved that day by his brother, Mordecai. One of the most profound stories of Lincoln's memory was:

While Abraham Lincoln and his three boys, Mordecai, Josiah and Thomas, were planting a cornfield on their new property, Native Americans attacked them. Abraham was killed instantly. Mordecai, at fifteen the oldest son, sent Josiah running to the settlement half a mile away for help while he raced to a nearby cabin. Peering out of a crack between logs, he saw an Indian sneaking out of the forest toward his eight-year-old brother, Thomas, who was still sitting in the field beside their father's body. Mordecai picked up a rifle, aimed for a silver pendant on the Native American's chest, and killed him before he reached the boy.[5]

Kentucky

Between September 1786 and 1788 Bathsheba moved the family to Beech Fork in Nelson County, Kentucky, now Washington County, (near Springfield).[lower-alpha 3] A replica of the cabin is located at the Lincoln Homestead State Park.[12] As the oldest son, and in accordance with Virginia law at the time, Mordecai inherited his father's estate and of the three boys seems to have inherited more than his share of talent and wit.[5] Josiah and Thomas were forced to make their own way. "The tragedy," wrote historian David Herbert Donald, "abruptly ended his prospects of being an heir of a well-to-do Kentucky planter; he had to earn his board and keep." [5] From 1795 to 1802, Thomas Lincoln held a variety of ill-paying jobs in several locations.[13]

He served in the state militia at the age of 19 and became a Cumberland County constable at 24.[14] He moved to Hardin County, Kentucky in 1802 and bought a 238-acre (1.0 km2) farm the following year for £118; It was located seven miles north of Elizabethtown, Kentucky[14] on Mill Creek.[15] When he lived in Hardin County, he was a jury member, a petitioner for a road, and a guard for county prisoners. Lincoln was also active in community and church affairs in Hardin County.[16] The following year his sister Nancy Brumfield, brother-in-law William Brumfield and his mother Bathsheba moved from Washington County to Mill Creek and lived with Lincoln.[12][17][lower-alpha 4]

In 1805, Lincoln constructed most of the woodwork, including mantels and stairways, for the Hardin house, now restored and called the Lincoln Heritage House at Freeman Lake Park in Elizabethtown.[17] In 1806, he ferried merchandise on a flatboat to New Orleans down the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers on behalf of the Bleakley & Montgomery store in Elizabethtown.[16][15][14][19]

Marriage and family

Kentucky

On June 12, 1806, Thomas Lincoln married Nancy Hanks at Beechland in Washington County, Kentucky.[16][14] Nancy Hanks, born in what was Hampshire County, Virginia, was the daughter of Lucy Hanks and a man whom Abraham believed to be "a well-bred Virginia farmer or planter." She was also called Nancy Sparrow as the adopted daughter of Elizabeth and Thomas Sparrow.[14][20] Dennis Hanks, Abraham's friend and second cousin, reported that Nancy Hanks Lincoln had remarkable perception. Nathaniel Grisby, a friend and neighbor, said that she was "superior" to her husband. Nancy taught young Abraham to read using the Bible, and modeled "sweetness and benevolence". Abraham said of her, "All that I am or hope ever to be I get from my mother".[21]

Thomas Lincoln developed a modicum of talent as a carpenter and although called "an uneducated man, a plain unpretending plodding man", he was respected for his civil service, storytelling ability and good-nature. He was also known as a "wandering" laborer, shiftless and uneducated. A rover and drifter, he kept floating about from one place to another, taking any kind of job he could get when hunger drove him to it. Aside from making cabinets and other carpentry work, Lincoln also worked as a manual laborer.[12][15]

Their first child, a daughter named Sarah Lincoln, was born on February 10, 1807, near Elizabethtown, Kentucky, at Mill Creek.[15][22] By early 1809, Lincoln bought another farm, 300-acre (1.2 km2), near Hodgenville at Nolin Creek, located 14 miles southeast of Elizabethtown and near the home of Betsy (Elizabeth) and Thomas Sparrow.[15][22] Although their cabin was a standard dirt floor, one room log cabin, their property was named Sinking Spring Farm for the "magnificent spring that bubbled from the bottom of a deep cave."[15] On February 12, 1809, the Lincolns' second child, a son named Abraham Lincoln, was born.

Seeking more fertile property, Lincoln and his family moved to Knob Creek Farm in 1811. Situated 10 miles northeast of the Sinking Spring Farm on Nolin Creek, the Knob Creek Farm was also adjacent to the Louisville and Nashville Turnpike. It was at Knob Hill that Abraham had some of his first memories. For instance, he remembered the death of his parents' third child, his brother Thomas Jr. a few days after his birth in 1812. He also remembered the cultivation of corn and pumpkins and sometimes attending a limited, "A.B.C." school with his sister within a couple of miles of the family's cabin. It was while living at Knob Creek that Lincoln was made annual road surveyor and became 15th wealthiest of 98 property owners by 1814.[16][23][24][lower-alpha 5]

Lincoln lost farms three times after boundary disputes due to defective titles and Kentucky's chaotic land laws, complicated by the absence of United States land surveys and the use of subjective or arbitrary landmarks to determine land boundaries. He did not have the money to pay attorney's fees to resolve title disputes, such as liens against previous owners and survey errors. In addition, as a farmer, Lincoln was unable to compete with those who had slaves to work their fields.[26]

Reluctant to discuss the extreme poverty of his youth, Abraham Lincoln quoted Gray's Elegy in 1860, saying his life could be summed up as "The short and simple annals of the poor." Without the food and clothing that they needed, they were considered among the "very poorest people" while in Kentucky. Abraham recounted years later, in a discussion with homeless boys in New York, that he had been poor and could remember "when my toes stuck out through my broken shoes in the winter; when my arms were out at the elbows; when I shivered with the cold."[27]

Thomas Lincoln moved the family to Indiana in December 1816, and purchased land in accordance with the land ordinance of 1785, partly because slavery had been excluded in Indiana by the Northwest Ordinance. Abraham Lincoln claimed many years later that his father's move from Kentucky to Indiana was "partly on account of slavery, but chiefly on account of the difficulty of land titles in Kentucky."[26]

Indiana

In December 1816, the Lincolns settled in the Little Pigeon Creek Community in what was then Perry County and is now Spencer County, Indiana. There Thomas and Abraham set to work carving a home from the Indiana wilderness. Father and son worked side by side to clear the land, plant the crops and build a home. Thomas also found that his skills as a carpenter were in demand as the community grew.[16][28] Nancy's aunt Elisabeth Sparrow, uncle Thomas Sparrow, and cousin Dennis Hanks settled at Little Pigeon Creek the following fall. While Abraham was ten years younger than his second cousin Dennis, the boys were good friends.[29][30]

In October 1818, Nancy Hanks Lincoln contracted milk sickness by drinking milk of a cow that had eaten the white snakeroot plant. There was no cure for the poison and on October 5, 1818, Nancy died.[31][32][lower-alpha 6]

Abraham and Sarah Lincoln, as well as Sophie and Dennis Hanks (whose guardians had also died of milk sickness), lived alone for six months when Lincoln went back to Kentucky to seek a bride and courted Sarah Bush Johnston, a widow from Elizabethtown, Kentucky.[33] On December 2, 1819, he married her and she brought her three children, Elizabeth, Matilda, and John, to join Abe, Sarah, and Dennis Hanks to make a new family of eight.[31][34][lower-alpha 7] Lincoln assisted in building the Little Pigeon Baptist Church, became a member of the church, and served as church trustee. By 1827, Lincoln had become the proud owner of 100 acres of Indiana land.[16]

The family continued to live in extreme poverty in Indiana, according to family members, neighbors, and friends. There were times that the only food in the house was potatoes, and the children did not have sufficient clothes to wear. Abraham was not invited to a wedding because he did not have appropriate clothes to wear. Sarah was taken in by a local family and earned her room and board by performing housekeeping chores. Abraham's life was considered "one of hard labor and great privation."[35]

David Herbert Donald, noting that Thomas Lincoln's eyesight began to fail in the 1820s, described his struggle to support his family:

In the early 1820s, Lincoln was under considerable financial pressure after his second marriage as he had to support a household of eight people. For a time he could rely on Dennis Hanks to help provide for his large family, but in 1826 Dennis married Elizabeth Johnston, Sarah Bush Lincoln's daughter, and moved to his own homestead. As Abraham became an adolescent, his father grew more and more to depend on him for the "farming, grubbing, hoeing, making fences" necessary to keep the family afloat. He also regularly hired his son out to work for other farmers in the vicinity, and by law he was entitled to everything the boy earned until he came of age.[36]

Illinois

Lincoln had a restless nature, and when John Hanks, a cousin who had once lived with the Lincolns, moved to Illinois and sent back glowing reports of fertile prairie that didn't need the backbreaking work of clearing forest before crops could be planted, he sold his Indiana land early in 1830[37] and moved first to Macon County, Illinois, west of Decatur and eventually to Coles County in 1831. The homestead site on Goosenest Prairie, about 10 miles (16 km) south of Charleston, Illinois, is preserved as the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site, although his original saddlebag log cabin was lost after being disassembled and shipped to Chicago for display at the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition. Lincoln, already in his fifties, remained a resident of the county for the rest of his life. In 1851, at the age of 73, Lincoln died and was buried at nearby Shiloh Cemetery, which was 3 miles from his home. Sarah, his widow, remained at their home until her death in 1869.[16][38] '

Relationship with Abraham

During Lincoln's youth, and particularly after the death of his mother, Abraham's relationship with his father changed and became increasingly strained. Due to his failing eyesight and likely declining health, Lincoln relied on Abraham to perform work needed to run the farm. He also sent Abraham to work for neighbors, generating money for Thomas. Michael Burlingame, in his book The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln classified Abe's subservience: "Abraham Lincoln was like a slave to his father," he penned in a secret biography.[39][40]

Historians differ on Thomas' parental treatment of Abraham. Burlingame, citing testimony from Lincoln relatives like Dennis Hanks, characterized Thomas as abusive and hostile to his son's efforts to better himself, saying he "avoided whipping or scolding his son in front of visitors but would administer punishment after they had left."[41] David Herbert Donald, citing similar testimony, concluded that Thomas, "generally an easygoing man ... was not a harsh father or brutal disciplinarian," and noted that Thomas enrolled his children in public schools during the few periods when they were available to the family. He quoted Sarah Bush Lincoln, Abraham's stepmother, who said that "Mr. Lincoln never made Abe quit reading to do anything if he could avoid it. He would do it himself first."[42] Both Burlingame and Donald agree that Thomas struck his son if he appeared overly neglectful of his chores, or if he thrust himself into adult conversations. As Abraham got older, he eagerly awaited coming of age so that he could move away and have as little to do with his father as possible.[43]

Although the degree to which it impacted their relationship is not clear, there seemed to be a struggle between Abraham's yearning for knowledge and Thomas' lack of understanding about the importance of study to Abraham's life. Abraham seemed particularly critical of his father's lack of education and lack of an earnest drive to see that his children received a good education. Historian Ronald C. White wrote that negative portraits of Thomas Lincoln come "from a son who said his father 'grew up literally without education,' the very value Abraham Lincoln would come to prize the most."[44] Abraham Lincoln, in turn, appears to have been unaware of his father's early struggles, particularly how the death of his grandfather forced Thomas to become a laborer: "Abraham Lincoln never fully understood how hard his father had to struggle during his early years. It required an immense effort for Thomas, who earned three shillings a day for manual labor or made a little more when he did carpentry or cabinetmaking, to accumulate enough money to buy his first farm."[15] Father and son also differed in their beliefs about religion; Thomas was a conventional Baptist. Growing up in a nonconformist household, Abe developed on his own as a free-thinker. Lastly, some say that Thomas favored John Johnston, his stepson, over Abraham.[39][40] Their relationship had become strained after Abraham left his father's house and even more so after Abraham reluctantly bailed Thomas out of financial situations. His stepbrother, John D. Johnston, also made repeated requests for money.

Although Abraham provided financial assistance on a few occasions and once visited Thomas during a bout of ill-health, when he was on his deathbed Abraham sent word to a stepbrother to: "Say to him that if we could meet now, it is doubtful whether it would not be more painful than pleasant; but that if it be his lot to go now, he will soon have a joyous meeting with many loved ones gone before; and where the rest of us, through the help of God, hope ere-long to join them."[lower-alpha 8] Abraham preferred not to attend his father's funeral and would not pay for a headstone for his father's grave. Aside from the strained and distant relationship between father and son, Abraham's actions may have been influenced by a "painful midlife crisis" and depression.[39][40]

During Thomas Lincoln's lifetime, he and his wife were not invited to Abraham's wedding and never met Abraham's wife or children.[46] David Herbert Donald stated in his 1995 book Lincoln that "In all his published writings, and indeed, even in reports of hundreds of stories and conversations, he had not one favorable word to say about his father."[39][40] Abraham, did, however, name his fourth son Thomas, the choice of which, Donald speculates, "suggested that Abraham Lincoln's memories of his father were not all unpleasant – and perhaps hinted at guilt for not having attended his funeral."[47]

Abraham, likely in response to his unhappy relationship with his stern, demanding father, was a caring and indulgent father with his own children.[48]

Religion

As a young man, Lincoln became active in the Primitive Baptist church (also known as Predestinarian or Separate Baptists), and eventually became a leader in the denomination. According to several historians, Thomas Lincoln was "one of the five or six most important men" among the Indiana Separates, and "for all effective purposes, Abraham Lincoln's life in Indiana was lived in an atmosphere of what William Barton called 'a Calvinism that would have out-Calvined Calvin.' "[49] In Indiana, Lincoln served as a trustee of the Pigeon Creek Baptist Church and helped to build the church meeting house with Abraham.[16] Thomas Lincoln had religious grounds for disliking slavery, and these served as a partial reason for moving from Kentucky to north of the Ohio River where slavery had been prohibited by the Northwest Ordinance of 1787.[26] After moving to Coles County, Illinois, Lincoln and his wife became Church of Christ members.[50]

Portrayals

A 1970 episode of Daniel Boone, although fictionalized, portrays the courtship of Thomas Lincoln (played by actor Burr DeBenning) and Nancy Hanks (Marianna Hill). Sarah Bush Johnston is referred to but not seen. It is mentioned that the couple will name their first son after Tom's father, Abraham. Daniel remarks, "He might even be President someday."

Films

| Date | Title | Portrayer | Country | Notes | IMDB |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1924 | The Dramatic Life of Abraham Lincoln | Westcott Clarke | USA | Directed by Phil Rosen | |

| 1930 | Abraham Lincoln | W. L. Thorne | USA | Directed by D.W. Griffith | |

| 1940 | Abe Lincoln in Illinois | Charles Middleton | USA | Directed by John Cromwell | |

| 2012 | Abraham Lincoln vs. Zombies (fiction) | Kent Igleheart | USA | Directed by Richard Schenkman | |

| Abraham Lincoln: Vampire Hunter (fiction) | Joseph Mawle | USA | Directed by Timur Bekmambetov | ||

| 2013 | The Green Blade Rises | Jason Clarke | USA | Directed by A.J. Edwards |

See also

Notes

- 1 2 Thomas' year of birth is stated by the National Park Service as 1778.[lower-alpha 9] When Thomas died, Abraham Lincoln reported that he had been 73 years and 11 days old, which would have made his date of birth January 6, 1778.[lower-alpha 10] Burlingame states that he was born about 1776.[lower-alpha 11]

- ↑ Abraham Lincoln commented in 1858 that he thought his ancestor settled in Hingham in 1638.[2][3]

- ↑ Lincoln is believed to have built a cabin for the Lincoln family before his death in May, 1786. He purchased a 100-acre piece of his property along a creek known now as Lincoln Run in the Beechland neighborhood from Richard Berry, Sr. in 1781 or 1782. The neighborhood was a piece of land created by a horseshoe bend in the Beech Fork River.[7][11] There is also a theory that Bathsheba moved to the Springfield area because Abraham's cousin, Hannaniah Lincoln, had borrowed money to purchase property there but had never repaid the debt. Whether that occurred or not is unclear, but she apparently lived at Hannaniah's home before moving to Beechland.[12]

- ↑ Bathsheba Lincoln, Nancy Lincoln and William Brumfield, and Mary Brumfield Crume are buried at the Lincoln Memorial Cemetery which overlooks Mill Creek in Fort Knox.[18]

- ↑ Carl Sandburg claimed that Lincoln purchased 348.5 acres at Hodgenville, paying $200 in cash to Isaac Bush and taking over a small previous debt.[25]

- ↑ She may have had contributing factors or causes of her death, as discussed in the Nancy Lincoln article.

- ↑ The children thought that Lincoln would be gone for three months. When six months had passed, they believed that he had died. The children were claimed to have been near-starved and in want of clothing while alone. For more than one year following her mother's death and until the arrival of Sarah Bush Lincoln, Thomas's daughter Sarah was responsible for the household duties her mother had performed.[33]

- ↑ Carl Sandburg also reported that Lincoln wrote the following to his stepbrother John Johnston: "I feel sure you have not failed to use my name, if necessary, to procure a doctor, or any thing else for Father in his present sickness. My business is such that I could hardly leave home now, if it were not, as it is, that my own wife is sick-abed... I sincerely hope Father may yet recover his health; but at all events, tell him to remember to call upon, and confide in, our great, and good, and merciful Maker: who will not turn away from him in any extremity."[45]

- NPS & Thomas Lincoln – Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

- Lincoln 2008, p. 95.

- Burlingame 2013, p. 3.

References

- 1 2 Donald 2011, p. 20.

- ↑ Burlingame 2013, p. 1.

- 1 2 Fischer 1991, pp. 836–837.

- ↑ National Humanities Center.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Donald 2011, pp. 20–21.

- 1 2 3 4 Donald 2011, p. 21.

- 1 2 3 Davenport 2002, p. 4.

- ↑ Harrison 1935, pp. 280–286, 350–351.

- ↑ Lincoln 2008, p. 95.

- ↑ Davenport 2002, pp. 3–4.

- ↑ Lincoln Run, Washington County, Kentucky.

- 1 2 3 4 Kentucky Parks.

- ↑ Burlingame 2013, pp. 3–4.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Sandburg 2007, p. 12.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Donald 2011, p. 22.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 NPS & Thomas Lincoln – Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial.

- 1 2 Davenport 2002, pp. 6, 22.

- ↑ Radcliff Tourism.

- ↑ Campanella 2011, p. 10.

- ↑ Donald 2011, pp. 20, 23.

- ↑ Goodwin 2006, p. 47.

- 1 2 Davenport 2002, p. 12.

- ↑ Donald 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ↑ Sandburg 2007, pp. 15, 20.

- ↑ Sandburg 2007, p. 15.

- 1 2 3 Donald 2011, pp. 23–24.

- ↑ Burlingame 2013, pp. 15–17.

- ↑ Donald 2011, pp. 24–25.

- ↑ Davenport 2002, pp. 29, 33.

- ↑ Center for History.

- 1 2 Sandburg 2007, p. 22.

- ↑ Organization of American Historians 2009, p. 89.

- 1 2 Burlingame 1997, pp. 94–95.

- ↑ Donald 2011, pp. 26–28.

- ↑ Burlingame 2013, pp. 16–17.

- ↑ Donald 2011, p. 32.

- ↑ Donald 2011, p. 36.

- ↑ History Illinois.

- 1 2 3 4 Donald 2011, pp. 32–33, 48–49, 102–103, 109, 152–153.

- 1 2 3 4 Burlingame 1997, pp. 37–42.

- ↑ Burlingame, Michael (2008). Abraham Lincoln: A Life, Vol. 1 (Paperback ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. pp. 10–11.

- ↑ Donald, David Herbert (1995). Lincoln (Paperback ed.). New York: Simon & Schuster. pp. 29, 32.

- ↑ Pokorski, Doug. "The sad tale of Thomas Lincoln". State Journal-Register. Springfield, Illinois. Retrieved December 27, 2017 – via Abraham Lincoln Online.

- ↑ White 2009, p. 13.

- ↑ Sandburg 2007, p. 70.

- ↑ Thornton 2010, p. 5.

- ↑ Donald 2011, p. 154.

- ↑ Burlingame 1997, pp. 63–64, 68.

- ↑ Guelzo 2009, pp. 33–34.

- ↑ Martin 1996.

Sources

- Burlingame, Michael (1997). The Inner World of Abraham Lincoln. University of Illinois Press. pp. 94–95. ISBN 0252066677.

- Burlingame, Michael (2008). Abraham Lincoln: A Life. JHU Press. pp. 3–11. ISBN 978-0-8018-8993-6.

- Campanella, Richard (December 13, 2011). Lincoln in New Orleans (PDF). University of Louisiana at Lafayette. p. 10. ISBN 978-1-935754-14-5.

- Center for History. "Indiana History – Indiana, the Nineteenth State (1816)". Center for History. Archived from the original on October 27, 2012. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

- Davenport, Don (January 1, 2002). In Lincoln's Footsteps: A Historical Guide to the Lincoln Sites in Illinois, Indiana, and Kentucky. Trails Books. ISBN 978-1-931599-05-4.

- Donald, David Herbert (December 20, 2011) [originally published in 1995]. Lincoln. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1-4391-2628-8.

- Fischer, David Hackett (1991). Albion's Seed: Four British Folkways in America. Oxford University Press paperback. p. 837. ISBN 9780199742530.

- Goodwin, Doris Kearns (September 26, 2006). Team of Rivals: The Political Genius of Abraham Lincoln. Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-7432-7075-5.

- Guelzo, Allen C. (January 26, 2009). Abraham Lincoln as a Man of Ideas. SIU Press. pp. 33–34. ISBN 978-0-8093-2861-1.

- Harrison, J. Houston (1935). Settlers by the Long Grey Trail. Joseph K. Ruebush Co..

- "Illinois Historical Markers by County – Coles". History Illinois. Archived from the original on November 1, 2013. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

- Kelly, Andrew (2015). Kentucky by Design: The Decorative Arts and American Culture. University Press of Kentucky. ISBN 978-0-8131-5567-8.

- Kentucky State Parks. "Lincoln Homestead State Historic Site Historic Pocket Brochure" (PDF). Kentucky State Parks. Archived from the original (PDF) on October 31, 2013. Retrieved March 22, 2013.

- "Lincoln Run, Washington County, Kentucky". Retrieved March 25, 2013.

- Lincoln, Abraham (October 2008). The Collected Works of Abraham Lincoln. Wildside Press LLC. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4344-7706-4.

- McMurtry, R. Gerald; Warren, Louis Austin (1960). The Thomas Lincoln Mill Creek Farm. Lincolnania Publishers.

- Martin, Jim (1996). "The Secret Baptism of Abraham Lincoln". Restoration Quarterly. 38 (2). Archived from the original on February 23, 2003. Retrieved August 14, 2016.

He was a consistent member through life of the Christian Church or Church of Christ

- National Humanities Center. "What About Slavery is Unchristian?" (PDF). Religion III – Slavery. National Humanities Center. pp. 1–6. Retrieved March 20, 2013.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Thomas Lincoln". Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. National Park Service. Retrieved March 21, 2013.

This article incorporates public domain material from "Thomas Lincoln". Lincoln Boyhood National Memorial. National Park Service. Retrieved March 21, 2013.- Organization of American Historians (2009). Sean Wilentz; Organization of American Historians (eds.). The Best American History Essays on Lincoln Best American History Essays. Macmillan. p. 89. ISBN 978-0230609143.

- "Radcliff & Fort Knox: Lincoln in North Hardin County". Radcliff/Ft. Knox Tourism & Convention Commission. Archived from the original on March 4, 2013. Retrieved March 26, 2013.

- Sandburg, Carl; Goodman, Edward C. (2007). Abraham Lincoln: The Prairie Years and the War Years. Sterling. ISBN 978-1-4027-4288-0.

- Thornton, Brian (2010). 101 Things You Didn't Know About Lincoln: Loves And Losses! Political Power Plays! White House Hauntings!. Adams Media. p. 5. ISBN 978-1440518256.

- Winkle, Kenneth J. (2011). Abraham and Mary Lincoln. SIU Press. pp. 4. ISBN 978-0809330492 – via Concise Lincoln Library.

- White, Jr., Ronald C. (2009). A. Lincoln. ISBN 978-1-4000-6499-1.

Further reading

- Coleman, Charles H.; Coleman, Mary (March 17, 2015). Thomas Lincoln: Father of the Sixteenth President. iUniverse. ISBN 978-1-4917-5927-1.

- Taylor, Daniel Cravens (26 July 2019). Thomas Lincoln: Abraham's Father. Beacon Publishing Group. ISBN 978-1-949472-75-2.

External links

- National Park Service, Abraham Lincoln's Birthplace at Sinking Spring Farm

- National Park Service, Abraham Lincoln's Boyhood Home at Knob Creek

- Thomas Lincoln's restored home at the Lincoln Log Cabin State Historic Site.

- The Lincoln Family in Northern Hardin County at Radcliff / Ft. Knox Convention & Tourism Commission.